| |

"'Every Debit must have its corresponding Credit,' explained Christie, "Perhaps every bad must have its corresponding good. An extension might be called Moral Double-Entry." |

| |

B.S.

Johnson – Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry |

Christie

Malry is a simple man. Determined to improve his lot

by becoming an accountant, he instead uses his new-found

understanding of double-entry book-keeping to draw up

a reckoning between himself and society at large, placing

a value on every wrong done against him with the aim

of extracting a similar value back through increasingly

extreme means.

B.S.

Johnson's 1973 novel Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry is a fascinating work on both a narrative and technical

level, working as both a novel and an anti-novel,

an example of post-modernist literature written long before post-modernism

became the creative curse that it is today. Its central

concept was straightforward, but is inventively and at times

ingeniously handled, while its casual rejection of the moral

values of society is both surprising and strangely satisfying.

Throughout the story, Johnson draws the reader's attention to the fact that

we are reading a novel, and in one chapter engages

in direct dialogue with his lead character about the

nature of the narrative he is participating in. Anyone attempting

to make a film of such a work, one that is going to

connect with an audience and affect them on an emotional and intellectual level, is taking on one hell of a challenge.

That screenwriter Simon Bent and director Paul Tickell

took on this task is admirable, and that they didn't completely

nail it is simultaneously unsurprising and a little disappointing.

But they have still created a film that intermittently

captures the anarchic spirit of the novel and that is

still a very worthy and sometimes satisfying work. That it has, however, remained

largely unseen in the very country in which it was created

is more than a little dispiriting.

So

what happened here? Why was this BAFTA-nominated film not more widely released

and seen? I mean,

how many inventive, original British features actually

appear each year? And when one does come along,

why is it almost immediately buried? Well there are

a number of reasons, none of which cut any ice with me.

The novel itself, though acclaimed and recognised as

an important work, is not as widely known nowadays as

it probably should be, and is hardly going to find itself on

the GCSE English reading list. No instant

tie-in hook there, then. And then there is the character of Christie

himself. He's a million miles from the do-good heroes of

the Hollywood mainstream, a man who effectively declares war

on society and quickly graduates from small-time

vandalism to mass murder. Christie is an amoral domestic terrorist

who destroys not for political or ideological reasons,

but to balance his reckoning with anyone he has issues with, which would probably include a sizeable proportion of any potential audience. Starting

to see the problem? Well there's more. Having completed the film, the filmmakers were having trouble nailing a distribution deal,

and some months later it still had not made its way into UK

cinemas. Then on September 11th 2001, the World Trade Centre attacks transformed western attitudes to terrorism of any sort, and no-one

wanted to touch this movie. It was to be almost another

year before Christie Malry was to get

it's overdue cinema release, and even then it was pulled after only a few screenings. It eventually crept out on

DVD, virtually unnoticed and at a budget price. This is all

wrong. I may have issues with certain aspects of the

film (and the DVD, as it happens), but it's still a

classily made, often inventive, and in many ways unique

work that has one thing most recent British and American

movies tragically lack: it has balls.

The

traditional route to audience identification of creating a sympathetic lead character really wasn't open to the filmmakers

here. Malry is an urban terrorist with essentially

selfish motives, but screenwriters Simon Bent and Paul

Tickell have recognised up front that a character does

not necessarily have to be likable to be interesting,

and Christie is certainly that. Shrugging off the book's

own pre-post-modernist style, director Tickell adopts

a very formal approach, a mixture of carefully composed,

locked-down compositions, smoothly executed tracks and eye-catching

top shots. This gives the film a very observational

feel and creates a reality that is also a little unreal,

something reflected in the non-naturalistic

but still engaging performances. Nick

Moran plays Christie as a man who is two steps away from grounded reality,

an ordinary bloke who has been slowed down to 33rpm. He perhaps takes Johnson's description of him as "a simple man"

a little too literally, but still nicely underplays a part that could so easily have been camped up. When

he tells girlfriend Carol (referred to simply as The Shrike

in the novel) that he loves her, for example, there is an

almost comic edge to his vocal delivery, one underscored by an oddly convincing sincerity. We never get really close to Christie,

but the nature of his quest and his own moral ambiguity

keep him at just the right distance for an audience to find interesting and not feel betrayed by his actions

or behaviour.

It

is to the filmmakers' considerable credit that they

have been largely faithful to the novel, which can't

have been an easy sell when trying to raise the budget,

and the film is at its strongest when it adheres to Johnson's vision. This goes beyond the recognition

factor of seeing something you admire in print being reproduced

faithfully on screen; for evidence of this, you only

have to look at the scenes that were not in the novel,

which for the most part simply do not measure up. The

most glaring example is the attempt to expand on the

novel's intermittent quotes from Fra Luca Bartolomeo Pacioli (the Benedictine

monk who, in his 1494 work Suma de Arithmetica Geometria

Proportioni et Proportionalita, was the first to be credited

with devising a system of double-entry

book-keeping) by intercutting Christie's story with a series of extended

fifteenth-century flashbacks detailing Pacioli's relationship

with Leonardo Da Vinci. Lushly photographed and sincerely

performed, they may well tell an interesting tale in

themselves, but it isn't half as interesting as the

one being told about Christie in modern times. And broken up into small

segments which have only a minimal link to the main

story, they are difficult to engage with on more than a superficial level, acting as interruptions to the real meat of the film. Without these flashbacks,

which have the content, character and tone of a more

traditional historical drama, Christie Malry's

Own Double-Entry would come close to anarchist

cinema, (largely) refusing to pass judgment on its

protagonist and genuinely fascinated and at times almost delighted by his actions. For a conservative

audience this will definitely pose a problem, but for those of us depressed by the twee Britishness

of the likes of Notting Hill, Love

Actually or Wimbledon and the like, such an approach is genuinely liberating.

Well,

almost.

There

is a purity to Johnson's vision of Malry's odyssey that

makes the story work as well as it does. Though

the film-makers have largely adhered to this approach, they have

added the suggestion, confirmed by the commentary

track, that Christie is also irresistibly drawn to the

sound of breaking glass, supposedly triggered by

the noise a bottle being smashed during his conception.

This can't help but dilute the single-minded simplicity

of Christie's purpose, suggesting that rather than making

a deliberate decision, he is in fact responding to an

unconscious need that has been with him since birth.

This also gives rise to one of those scenes

that always get my back up, where a song on the soundtrack

spells out what his happening on screen – as Christie

blows up a tax office, we are treated to a (rather

good, it has to be said) version of I Love the Sound

of Breaking Glass, which is followed with

an on-screen hailstorm of, yes, broken glass. This is

a real shame, as elsewhere Luke Haines' simple but haunting

score is most effectively used.

Spoiler

alert: If you don't want advance information

on scenes towards the end, and the end itself, skip

past this section by clicking here.

It's

after this that the cracks really start to show and

the inventiveness and originality begin to slip.

A scene in which Christie's mother and

his workmate Headlam turn up in a bar to play Angel

and Devil and rather obviously debate the morality of

Christie's actions is clunky and unnecessary, and the

pub revolutionaries, who were represented only by their

dialogue in the book, stretch the concept of cartoon

characterisation a little too far.

A bigger problem,

especially for those who know the novel, is how the story concludes (last chance to bail out!). In Johnson's original, Christie discovers a lump which is diagnosed as cancer, which very rapidly

brings his life to an end (in a chapter ironically titled Now

Christie really does have Everything), an event whose random nature he is unable to build into his reckoning

and results in him ultimately canceling his debt.

In the film he is blown up by one of his own bombs

on the way to destroying the Houses of Parliament, a

twist that can't help but seem contrived and judgemental

– he who lives by the bomb, dies by the bomb. It almost feels designed to provide a sense of poetic justice for those who regard Christy's actions as unforgiveable, deflating the film's previously potent sense of liberation and moral ambiguity. This is

followed by a funeral that seems to mock Christie's

antipathy towards religion, and a completely unnecessary and horribly misjudged scene

in which his girlfriend Carol discovers Christie's ledger and his drawings and plans, a scene made all the more

unpalatable by a cheesy round-up montage of earlier

scenes.

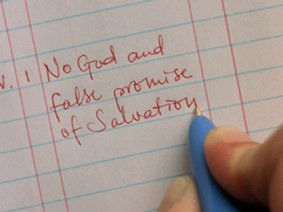

All

of which is a huge shame, as together with the distracting

trips back to the fifteenth century, this cuts an intriguing and sometimes brave piece of work off at the knees. But I would still suggest that the bits that do work are a lot more inventive, interesting and

chance-taking than most other recent British films are in their entirety. The sense of refreshingly amoral anarchy survives largely intact, and the technical

handling is often very impressive, repeatedly belying

the film's small budget. The film, like Johnson's

story, appeals to that dark little part of us that, after

a day of being repeatedly wound up by the thoughtless idiots, wants to go nuts in a supermarket

with a tommy gun. And I've personally got a soft spot for

any film in which the lead character cheerily dismisses

the church as corrupt and deceptive, and reasons

that he is owed recompense by society because of "No

God and false promise of salvation."

In

some ways this is a very good transfer. Colours are strong,

sharpness is good and black levels are generally spot on.

There is minor artefacting in areas of one colour in places,

but it is rare. The problem is that we have not the anamorphic

widescreen print the film demands, but a cropped 4:3 one,

which really does mess with Reinier van Brummelen's handsome

photographic compositions. To make matters worse, the opening

credits are in non-anamorphic 1.85:1. Thus, despite a decent

selection of extras, there is a sense of a half-arsed job

here that director Tickell should complain bitterly about.

The

soundtrack is Dolby 2.0 stereo, but the separation is often

very good and the tonal range excellent. If you have DSP

modes on your amp, re-channel the bass through the subwoofer

and you get some kick-arse low frequencies in places. 5.1

would have been nice, of course, but as Dolby 2.0 tracks

go, this is a good 'un.

Considering

this disk can be picked up for about a fiver and the picture

has been cropped, the number of extras on offer here is

genuinely surprising.

The

first is the best, a screen-specific commentary with director Paul Tickell and lead actor Nick Moran,

though neither are identified by name on either the menu

or the track itself (the DVD case misleadingly

suggests that there are two seperate commentaries). This is an

informative and sometimes entertaining listen, giving plenty

of background on the making of the film, and certainly

answered some questions I had about how they obtained permission to film a scene in which Christie poisons the water supply at a real water processing plant. There are, however, a couple of technical issues. Putting aside the

fact that there is no film sound at all (comments on dialogue

are thus a tad abstract), there are a couple of loud pops,

and the commentary itself is out of sync with

the screen action by a good fifteen seconds, resulting

in sometimes animated discussion on a shot or sequence that has not yet appeared. This is shoddy stuff, and should have been picked

up on before release.

The trailer sells the film rather

well (not much use if no cinema shows it, of course) and

is presented non-anamorphic 1.85:1, so is in the correct

aspect ratio, something the main feature is not, which has the effect of rubbing more salt in the aspect ratio wound.

The photo gallery is a one minute

montage of production stills set to music. To be honest

they all look as if they've been grabbed from the film

itself. A 1.85:1 version, no less.

Film

and characters is a 4 minute featurette about, well, the film and its

characters. The interviews are not presented full screen,

but in small windows while animated lines form boxes on

screen. Hmmmm. Moran casts Malry here in a surprisingly

negative light.

Novel

to screen is a three-and-a-half minute featurette

consisting of interviews with writer Simon Bent, director

Paul Tickell and lead actor Nick Moran in which they discuss

the process of adapting Johnson's book for this film.

The line/box style of the previous featurette is reproduced

here.

Soundtrack runs six minutes forty-nine seconds and discusses the

creation of the music score, central to which is an interview

with composer Luke Haines. As with the preceding featurettes,

the presentation is a mixture of lines and boxes, but

again the content is interesting.

What

the papers said is a collection of carefully

selected short extracts from favourable reviews of the

film. A somewhat odd and rather insecure inclusion, as

by the time you get to this you will already have formed

your own opinion of the film, and one sentence is hardly

going to make you consider it in a different light.

Interview

with Paul Tickell is a textual extra in

which the director is interviewed by Richard Marshall

of 3 A.M. Magazine and discusses his approach to the film,

dismissing the idea of shooting dogme-style because he'd

already been down that path with his previous film Crush

Proof and because "every fucker does it."

He also has some interesting thoughts on British cinema

in general and those working in it. There are quite a

few pages to this and it makes for a worthwhile read.

Finally Alternative opening sequence is just that, lasting for two minutes and really making the 4:3 cropped picture of the main feature smart

by being non-anamorphic 2.35:1. There is no sound on this

sequence.

Several

years ago, when a misguided attempt was made to revive the

old TV music review show Juke Box Jury, singer Siouxsie

Sioux was asked to pass comment on an

innofensive but somewhat banal new single and memorably complained

that: "It's not dangerous, and so in a way, it is." This

nicely sums up a depressingly high percentage of recent

British cinema. It's nice to be entertained, but

art, great art, should definitely be dangerous. Christie Malry's

Own Double-Entry may, thanks to some clunky moments

and some misjudged wanderings from the source novel, falls

some way short of being great cinema, but it is technically

accomplished, imaginative and bold. And yes, in a time

when viewpoints are narrowing and terrorist paranoia is

rife, it is dangerous. And that is something to celebrate.

As

for the DVD, well the film deserves better. At a time when

anamorphic widescreen transfers are almost a given, what

the hell are we doing with this 4:3 cropped print? The extras

are rather good, but even here there are signs of shoddiness.

But with the film still struggling to find a large audience,

a re-release is unlikely, and it can be picked up very cheaply.

So check it out – flawed Outsider Cinema is still a damned

sight better than most of the more polished mainstream fare

out there.

|