"I do not propose to recount my life in any detail, what-is-what! No damned business of anyone, what-is-what! I am Lord Cardigan, that is what. Them cherrybums, you see 'em tight. My cherrybums, I keep 'em tight. Ten thousand a year out me own pocket I spend to clothe 'em! A master cutler sharps their swords and I keep 'em tight stitched, cut to a shadow! Good! If they can't fornicate they can't fight, and if they don't fight hard I'll flog their backs raw, for all their fine looks!"

That extraordinary little speech comprises the first spoken words in The Charge of the Light Brigade, the barked-out thoughts of Brigade commander Lord Cardigan in a film whose title inspires visions of triumphant heroism, dashingly dressed horseman galloping to victory in the Queen's good name. It's an image enhanced by the final verse of Lord Alfred Tennyson's popular poem of the same name:

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honour the charge they made,

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred.

It's famous opening verse is, however, a tad more foreboding:

Half a league half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

And we're into the second verse before the suggestion is made that maybe, just maybe, those at the top may have made a mistake or two:

Forward, the Light Brigade!'

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldier knew

Some one had blunder'd.

As those with an interest in history will be aware, the word 'blunder' doesn't really cover it. The charge itself, made at Balaclava against superior Russian forces in 1854 during the Crimean War, was an unmitigated military disaster, a gallop to death triggered by a combination of poor judgement, personal grudges, arrogance, misdirection and misunderstanding.

Inspired, no doubt, more by Tennyson's verse rather than factual records, the 1936 Hollywood version of the story turned disaster into heroic spectacle and had Errol Flynn leading the charge in revenge for the barbaric massacre of British women and children. Any relationship to historical truth was purely coincidental. Thirty-two years later, the story was retold from a rather different perspective, by a major British filmmaker making a statement about the futility of war at a time when the conflict in Vietnam had created an audience receptive to just such a message. The inspiration here was likely not Tennyson's poem but Cecil Woodham-Smith's The Reason Why, a detailed and meticulously researched study of the events leading up to the infamous charge and the personalities involved. Scripted by Charles Wood (he of The Knack...and How to Get It and Help!) from a first draft by celebrated playwright John Osborne (who is not credited) and directed by Tony Richardson (co-founder of the Free Cinema movement and the man behind Look Back in Anger and Tom Jones), the resulting film is a rich blend of historical truth, political satire and factual game-playing.

Central to Wood and Richardson's approach is Captain Louis Edward Nolan, played here with fiercely confident conviction by David Hemmings. Right from the start, Nolan is portrayed as the single determined progressive in an army mismanaged by daft old codgers and daffy upper-class fops, military men whose viewpoint is narrowed and hopelessly out-of-date. Unfortunate representative of this old guard view is the above-mentioned Lord Cardigan (a superb Trevor Howard), a figure whose loud vocal bluff, archaic prejudices and singular way with the English language paint him as someone trapped in a colonial past and only a few steps shy of barking mad. These two figures, both of them proud and stubborn in their way, clash immediately through Cardigan's outrage at Nolan's Indian manservant, a racial contempt he holds not just for non-whites, but any British soldier who served in India. It's a conflict that climaxes over a seemingly trivial manner, when Nolan orders a bottle of red wine at a dinner at which Cardigan has stipulated that only champagne should be drunk – his outraged bellow of "Black bottle!" becomes a taunt for press and public alike and a focus of the increasing embarrassment of his commanders at his image and behaviour. Cardigan holds his brother-in-law Lord Lucan (Harry Andrews, also excellent) in similar contempt, a loathing reciprocated every time the two reluctantly meet. On being told that his hated relative will command the Light Brigade, Lucan bellows "CARDIGAN?" with an incredulous outrage akin to Lady Bracknell's famous "handbag" exclamation in The Importance of Being Earnest, only with considerably more fury.

Wood and Richardson have clearly taken sides on a class divide that dominated British society at a time when military rank could be awarded as a badge of social standing rather than combat leadership experience. Just how much the pair exaggerate (or whether they do at all) is nigh on impossible to confirm or deny so long after the event, but I'm prepared to run with it in the name of political satire, despite a sense that a couple of characters would automatically qualify for entry in Monty Python's Upper Class Twit of the Year race. That said, the outlandish plum-voiced twittering of Peter Bowles' Paymaster Captain Duberly is, in an offhand but crucial moment, revealed to be largely a put-on performance designed to ingratiate himself with ludicrous popinjays of higher social standing.

Elsewhere, the behaviour and personal conflicts have considerable credibility. The manner in which Cardigan casually destroys the career of a professional soldier for – on a point of honour no less – refusing to spy on Nolan is a sobering illustration of a complete lack of empathy that the arrogant and powerful still exhibit to this day, and the fifty lashes administered to the same soldier for arriving on duty drunk the following day is a fair reflection of the levels of punishment that were once dished out. Even the infantile bickering of the commanders has an believable feel, with Lucan and Cardigan eventually reduced to calling each other childish names during the preparations for battle. In the manner of commanders for years to come, meanwhile, the polite and slightly befuddled Lord Raglan (a typically delightful John Geilgud) safely surveys the scene from a hilltop vantage point, where he confuses the present enemy with the traditional one – "Tell Lord Lucan the cavalry will advance on the French...er…the Russians..." – and plays genial host to an ailing French commander and Duberly's forwardly enthusiastic wife (Jill Bennett), whose fascination with Cardigan eventually lands her in his bed.

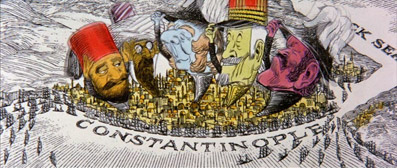

The satirical elements are at their artistic peak in Richard Williams' glorious animated links and title sequence, drawn in style of political cartoons of the Victorian era and regarded by a number of commentators as superior to the live action scenes they occasionally interrupt. It's an accusation that has dogged the film from its release to the present day, particularly from those who suggest that the film cannot decide whether it wants to be an anti-war political satire or a historical spectacle, seemingly unaware that it's perfectly possible to be both. Indeed, I'd argue that one of Richardson's key achievements here is that he so successfully packages the former inside the audience-friendly coat of the latter, allowing him the sort of production values that no indie political film could ever afford.

A little structurally fragmented it may be, and it does tend to focus on the foolishness of the commanders at the expense of any exploration of the sacrifice at troop level, but The Charge of the Light Brigade is still a consistently enjoyable and robustly performed slice of historical revisionism, one that plays entertaining and pertinent games with the key characters, but gets (most of) its facts straight in its presentation of events leading up to and during the fated final charge. Its dour view of the follies of military authority is certainly one-sided but appropriately so, given that men were still being sent to their deaths in great numbers by high command incompetence on the battlefields of Europe sixty years after the events portrayed here. And while we may now have officers who genuinely care about the fate of their troops, that doesn't stop the odd commander-in-chief from sending them all off to fight and die to protect the interests of those in positions of privilege and power.

A reasonable but not exactly exceptional anamorphic 2.35:1 transfer whose image quality varies quite a bit and sometimes on a shot to shot basis. At its best, the picture is crisp and detailed and its colour and contrast are finely balanced, but elsewhere it's a visibly soft, grainy and even a little muddy. I've read that there were similar issues with the previous BFI DVD release of the film, suggesting that we're looking at the same transfer here.

The soundtrack is a perfectly serviceable Dolby 2.0 mono – reasonably clear with only a slight background hiss and a narrower dynamic range than you'd find in combat scenes in more recent films.

Only the original Trailer (3:06), a solid sell that's true enough to the the film's spirit and is in surprisingly good shape (and is anamorphic scope). The disc does lose out here to the previous BFI release, though, which also included the 1912 silent film version, an interview with Richard Williams, and biographies of the Williams and Richardson.

Tony Richardson is a director whose later work is too often dismissed by those who mourn his wandering from the neo-realist path on which he made his name. I'm having none of it. The Charge of the Light Brigade may be a little ragged at the edges, but it's still a work to be treasured, for its performances and dialogue, for its blend of drama and satire on a grand scale, and for the sheer ambition of its writer(s) and director. The DVD is not all it could be and I live in hope that one day someone at Criterion will take a fancy to the film. In the meantime this will do well enough.

|