|

When he began work on Casa de Lava/House of Lava (also known by its perplexing, ill-fitting US title 'Down to Earth'), Pedro Costa envisaged it as a remake of Jacques Tourneur's I Walked With A Zombie. Conceptually, it's an intriguing idea, but visually, it's even more tantalising to consider. Already well aware of Tourneur's work, other RKO films of the period, and Costa's ability to draw out a spectrum of light and depth in black and white images, I expected to see a film similar to his debut feature, Blood/O'Sangue, one replete with chiaroscuro lighting, in which horror and the living dead would become, dare I say it... beautiful.

Those familiar with Costa's work will of course know that Casa de Lava is the first of his films to be shot in colour. Though that change certainly came as a surprise, what unfolded before me was far from a disappointment, but rather, a revelation.

Thanks to Costa and his cinematographer Emmanuel Machuel (already well-known for his acclaimed work with Robert Bresson, amongst others), I was about to see the world, or, more specifically, the picturesque islands of Cape Verde, as never before.

Casa de Lava begins violently, not with the bloody death of an innocent soon to be reborn as a zombie, but with volcanic eruptions, red-orange lava surging forth from black rock formations, which look like those of a planet in a galaxy far beyond the reaches of the craft that took Georges Méliès on a La Voyage dans la lune/A Trip to the Moon. These early scenes, shot with a documentarian's impulse, are initially confusing. In hindsight, they seem to be at odds with the rest of the film. However, when you do take time to reflect – and Casa de Lava is a film that will inspire much post-credits analysis – the sequence is actually a clever visual metaphor for the film's major themes. The lava, bursting free from the very depths of the earth, echoes the plight of nurse Mariana (Inês de Medeiros, also Costa's leading lady in Blood) and the other Cape Verdians. They too are trapped, fighting to break free, wanting to head for the Lisbon mainland, determined to make it before they die. Those lava flows also bring with them great menace and danger, an undercurrent present throughout the film. When the tension finally becomes too much, it's not lava that bursts through, but anger and often violence, frequently directed at the alien visitor Mariana.

From the moment she's set down with her unconscious patient, Leão (Isaach De Bankolé, familiar to fans of Claire Denis' Chocolat and 35 Shots of Rum), a construction worker left in a coma after an industrial accident, we know Mariana's journey back to her own home won't be easy, and the pilot's assurance that he'll soon return for her rings hollow. As she watches him and his co-pilot retreat back to their aircraft, she's dwarfed by the vast, deserted landscape, every inch the fish out of water. This is how she remains for the rest of the film. Unable to speak Creole, she finds it difficult to communicate with those around her, and though she repeatedly asks for them to speak Portuguese, they never entertain her request, and even as she begins to learn some of the language she grows evermore isolated. The basic island hospital is a world away from the one she's used to working in, leaving her constantly at odds with the other medical staff in their differing treatment of her patient.

In true horror style, though she doesn't know it yet, Mariana is the very definition of Carol Clover's 'final girl.' However, in Costa's world, there are no bloodthirsty vampires or crazed serial killers for her to outsmart. Instead, she's her own worst enemy. Cape Verde becomes her very own prison, despite the fact there are no locked doors to keep her there, just as Leão is trapped in his own body until he awakens. Like the unsuspecting outsiders of Roman Polanski's Chinatown and Robin Hardy's The Wicker Man, Mariana gets much more than she ever bargains for when she agrees to accompany Leão in the hope of finding his family as she nurses him back to health. Driven by her duty of care to remain at Leão's side, she becomes entangled in island life. After befriending local musician Bassoé (Raul Andrade, who also provides the film's music), she the finds herself administering vaccines to an increasing number of local children as they fall ill. Finally, she crosses paths with the mysterious Edith (celebrated French actress Edith Scob) and enters into a quasi-romantic dalliance with her son (played by another Blood alum, Pedro Hestnes). The longer Mariana stays on the island, the more she begins to stray from Leão. Very soon, the urgency of anything beyond Cape Verde's shores becomes a dim and distant memory.

At first, Casa de Lava presents itself as a simple tale, centred entirely on the fate of Leão and his journey to recovery. Appearances are deceptive though, and it quickly becomes clear that this is Mariana's story, and the effect that the islands and its inhabitants have upon her. Leão's sudden return to consciousness is treated as something of a non-event, which we are privy to well before Mariana is. At this point,

the film splinters off into a series of labyrinthine subplots, with an editing rhythm to match. Purposefully elliptical, it becomes more difficult follow. As the film changes shape and takes on a life of its own, the relationship between it and Tourneur's becomes little more than a tenuous distraction. For some, that level of confusion will infuriate, but for others, it will merely add to the film's uncanny ethereal appeal. Dependent on which school of thought you subscribe to, Casa de Lava will either rank as Costa's strongest film or his weakest, but no one will argue as to its unique qualities.

Costa admits that the film was made during a strange period in his life, at a time when lacked artistic direction. He became drawn to the islands and its people, and the equally strange effect they had upon him, saying that were it not for Casa de Lava, there would be no other film that bears his name as a directorial credit (for more on this, watch the interview with Costa included amongst the disc's supplemental features). Cape Verde's mythical potency certainly comes across on screen, almost as if it is impregnated in every frame, seeping between one and the next. That very draw made Costa abandon his original idea for the story, refocusing on the island, and shifting the story away from De Bankolé's character (a decision which reputedly led to director and actor coming to blows, De Bankolé being unhappy with the change of direction).

Mariana, then, becomes Costa's stand-in, her journey mirroring his own. Consequently, the film revels in its strangeness, with a kind of Lynchian delight. In line with the narrative tension, there's a stylistic one too. Casa de Lava is something of an exercise in stylised minimalism – the kind of which Bresson and Straub-Huillet would be proud. Though he's obviously influenced by their aesthetic and approach, it retains Costa's distinct grounded touch, which is very much in opposition to the esoteric feel (something he would explore further in Juventude em Marcha/Colossal Youth over a decade later). Casa de Lava's palette is rich and earthy, and Costa's play with depth, texture and sound remains evident. It works here on a visceral level to foreground both the harshness within nature and the beauty of the Cape Verde landscape – as in the sequences of waves crashing on to the shore, or those involving Mariana and the other islanders negotiating its rocky outcrops barefoot, basking in the warmth from the lava flows hidden beneath. Deft touches such as this make Mariana's suffocating, almost nightmarish predicament concrete, ensuring that Costa's fable-turned-fever-dream will stay with you long after the credits have rolled.

Don't be fooled by the grainy opening stock footage, once we move onto the film's human subjects the image quality is a showcase for how good a DVD transfer can look. The result of a new HD restoration supervised by Pedro Costa, the contrast is. for the most part (notably in the daylight exteriors), spot-on, the black levels crisp, the colours warmly attractive and, save for the odd interior shot, the grain is minimal. There's also not a dust spot to be seen. An excellent transfer.

The Dolby mono 2.0 stereo soundtrack has also been restored and is very clear and free of any hum, hiss or other blemishes. Stereo separation is minimal and confined largely to background effects, and even then is subtly employed.

Fans of Costa's work and aficionados of Second Run's output have much to celebrate here. Firstly, Casa de Lava arrives with a HD restoration of the film, supervised by the director, undertaken specially for the release (details on the team behind this can be found in the accompanying booklet). Secondly, it has a handsome collection of supplemental features that undoubtedly make the experience of Casa de Lava all the richer.

Pedro Costa on Casa de Lava (18:45)

Filmed at London's Tate Modern in 2009, a reflective Costa speaks at length about the film, his love of Jacques Tourneur, and the importance of Cape Verde to him as a filmmaker. Working during a time of political, social, and personal turmoil, Costa is candid about the difficulties he had getting the project off the ground and seeing it through to completion, describing it as his Apocalypse Now. Watching this interview underlines just how important an achievement Casa de Lava is, and proves there's a great deal more that goes into a film than we see on screen.

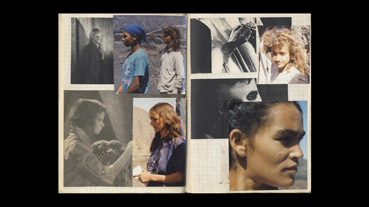

Casa de Lava Scrapbook (23:42)

Specially created for this release by Pedro Costa, this is by no means an ordinary slideshow gallery set to music. Instead, we're treated to pages from the notebook Costa used throughout the making of the film in Cape Verde, accompanied by ambient nature sounds edited by Henri Maikoff and original music from Raul Andrade. It makes for an immersing, visceral experience. A wonderful glimpse of the director's working methods and personal creative process, each page is a little gift in and of itself.

Interview with Cinematographer Emmanuel Machuel (07:58)

Presented without preface, the famed cinematographer speaks in his native French (subtitles are provided), recalling how he came to be involved in Casa de Lava, his experience of working with Costa, and their specific approach to the film's aesthetic. A great watch, and Machuel's warmth and affection for the man and the project certainly come through.

Booklet

Beautifully illustrated with stills, this is dedicated to an essay on Casa de Lava by renowned author-critic Jonathan Rosenbaum. Developed from previously published work in The Chicago Reader and Os Films de Pedro Costa/The Films of Pedro Costa, 'Eruptions and Disruptions in the House of Lava' is a wide-ranging piece that places the film within context of Costa's oeuvre, highlights the stylistic 'tug of war' between classical narrative and the director's unique picturesque style, and provides though-provoking analysis of both character and plot. Fascinating stuff.

Casa de Lava is a haunting and challenging film, which sets down many of the recurrent themes found within Pedro Costa's considerable body of work. A meditation on fear, loneliness, and the effects of postcolonialism, the film carries with it a brooding, dark undercurrent that contrasts sharply with the beauty of its images. A unique experience created by a man of singular gifts.

|