|

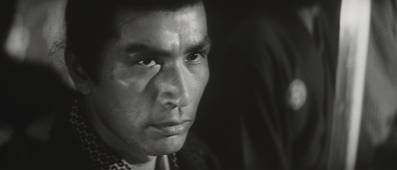

Masahiro

Shinoda's 1964 film Assassination [Ansatsu] kicks off with two minutes of voiced textual scene setting.

I'd read it if I were you, and carefully. You might even

want to make notes, as this not only sets up the historical

context for the film, it outlines events that have bearing

on and are intermittently referred to throughout the narrative.

It

would probably be fair to say that Assassination

was made primarily with a Japanese audience in mind, one

with a sound knowledge of their own history and able to

fill in the gaps that the film sometimes trots over. The

plotting here is complex and the narrative non-linear, so

dropping your concentration, even for a few seconds, could

well leave you scratching your head and wondering just who

this person is, why these events are taking place, and even

when they are occurring. It took me two viewings to get things really

clear, and assistance from a Japanese friend to appreciate

the historical elements and help separate truth from creative

storytelling.

The

arrival of The Black Ships in July 1853 was a crucial moment

in Japanese history. Commanded by Commodore Matthew Perry,

the five American warships arrived at Uraga Port in Edo

(now Tokyo) bearing a letter for the Emperor from US President

Fillmore requesting the opening of trade links with Japan,

effectively ending 300 years of national seclusion. The

issue divided the country – the Shogunate, who were fearful

of the Americans' superior firepower, were in favour of

a treaty, while the Emperor and his followers fiercely opposed

what they saw as a threat to The Divine Land.

The

film starts off ten years after this event, when the opposing factions

are still in often violent opposition. A skilled ronin

named Hachiro Kiyokawa, who has been convicted of killing

a policeman, is offered amnesty if he will gather together

unemployed samurai to protect the Shogun and defeat those

still loyal to the Emperor, to whom he was once loyal. He nevertheless accepts the undertaking, a move

that bemuses his previously loyal followers, some of whom

start plotting against him as a result. Although his new employers do

not trust him, they are aware that he is the perfect man

to organise their Free Samurai Army – or Shinsengumi – but

as a reserve plan they engage Tadasaburo Sasaki, a skilled instructor

at the nearby samurai school, as a potential assassin should the need arise.

Given

that the story revolves around Kiyokawa, on my first viewing

of the film I was a little surprised that it took so long

for us to connect with him as a character – in the

early scenes he is frequently observed either in wide shot

or with his face masked by a large straw hat, with full-face

close-ups reserved largely for later. But on

the second viewing it was clear that this is entirely

the point. This is less a story of Kiyokawa

the person than a gradual demystification of a man who has taken on almost

mythical status. It also has a specific narrative

purpose. Sasaki, charged the task of possibly having to

kill a swordsman whose skill is superior to his own, determines

to learn as much about Kiyokawa as he can, and our process

of discovery runs alongside his. Mind you, Sasaki's investigations

are driven only in part by his sense of duty – on their

first meeting, Kiyokawa humiliates him in front of his own

students by easily besting him in a fencing match, harming both

his pride and his reputation, both of which he becomes increasingly

desperate to restore. In addition, his understanding of

the man is only partial, as key information is revealed

not to him but to one of Kiyokawa's most loyal students,

who is conducting his own enquiry in an attempt to understand the

sudden side-switch of a man who once saved his life.

It

is with the onset of Sasaki's investigations that the film

begins time-flipping and sometimes unexpected details of

Kiyokawa's past are revealed. Though we are led clearly

into these sequences by a memory or a diary entry, the film

can hop out of them almost invisibly and not always return to the

pre-flashback location. It is in these scenes that the events

outlined in the opening are most frequently referred to,

including the story's first assassination, that of Premier

Ii, which those loyal to the Emperor see as the first major

step on their road to victory over the Shogonate supporters.

A lot of what takes place

here is based on historical fact. The arrival of the Black

Ships and the internal disputes that followed were events

that changed Japan forever, and the assassination of Premier

Ii was an actual occurrence that took place in March of

1860, something that shook the Shogunate and led to the

politically motivated marriage between Shogun Iemochi and

the Emperor's sister, Princess Kazu. Perhaps more surprising

to those new to these events is that Hachiro Kiyokawa was

also a genuine historical figure and the plan to recruit

large numbers of ronin for a Free Samurai Army is credited

to him, and he did indeed lead them to Kyoto as a bodyguard

force for Shogun Iemochi.* Specific incidents are even linked

historically significant events, such as the attack on the

Satsuma clan members at the Teradaya Inn (an event my friend

assures me took place but which I have been unable to independently

verify as yet), a venue that the following morning is visited

by Kiyokawa's friend Sakamoto, who observes the destruction

left by the fight and then sits down to mournfully sing.

This could almost be seen as a moment of premonition, as in 1866

rebel samurai Sakamoto Ryoma was ambushed at this very inn,

which was his favourite such establishment and home to his girlfriend Oryo

(he survived but was assassinated the following year). This

reference would definitely not be lost on a domestic audience,

for whom Ryoma remains a well known and respected figure – the Teradaya Inn still stands today and includes a memorial

to him. There is also a Sakamoto Ryomo memorial museum in Urado

Castle Park in Katurahama, and in 2003 the Kochi Airport

was renamed the Kochi Ryoma Airport in his honour.

Whether

the Kiyokawa of the film is ever really a likeable figure

is of little real consequence. There are no clear-cut heroes

and villains here and just about everybody appears capable

of acting without honour or concern for the fate of feelings

of others. Thus Kiyokawa's status as warrior of almost superhuman

fighting skills is tainted when he unexpectedly beheads

a policeman without provocation and is chased halfway across

town by an angry mob. Then again, the officials searching

for his whereabouts waste no time in beating and torturing

his girlfriend Oren, the one genuinely innocent player in

the piece and the only person Kiyokawa appears to connect

with on a meaningful level.

If

Assassination does not engage the emotions,

it certainly rewards the intellect and on the way provides

moments of genuine visual splendour, from Kiyokawa's night-time

fight with a group of ex-followers who feel betrayed by

his apparent switch of allegiance, to the eye-catching wide

shots (the scope frame is very well used here) of the Free

Samurai Army en route to Kyoto, and a gobsmaking high angle shot of the army sheltering under a sea of white

umbrellas. The process of uncovering the truth (well, the

film's version of it) about Kiyikawa is an engrossing and

sometimes surprising one and provides for an intriguingly

structured narrative and an involving finale. Just remember,

this is not one to run when you're getting a bit tired or

when you're dividing your time between the film and a noodle

dinner – bring your whole concentration to Assassination

and it will be rewarded.

Masters

of Cinema appear to have had problems with all of their

Shochiku sourced prints, and Assassination is no exception. Framed 2.35:1 and anamorphically enhanced,

the quality is somewhat variable – at best the contrast

and sharpness are rather good, but elsewhere black levels

have been strengthened at the expense of picture detail,

resulting in sequences that look muddy and shots where shadow

detail is non-existent. Brightness also varies,

sometimes from shot to shot, greying out the contrast in

places and darkening the picture noticeably in others. On

the plus side the print is virtually spotless, but this

is not one of Masters of Cinema's best transfers.

The

Dolby 1.0 mono track has a very slight hiss, expected for

a film of this period, plus the odd small pop, but is otherwise

more than serviceable.

The

subtitles are clear and a reasonable translation, but unusually

I spotted three typos, making me wonder if the subtitling

was done by Eureka or part of the package from Shochiku.

No

commentary on this one, but there is an Introduction

(9:36) by Alex Cox, whose enthusiasm for the film is certainly

infectious, and if the first viewing leaves you a little

baffled then this is as good a place to start for help with

the second.

There

is also a Gallery of 27 production stills

that are in good shape and reproduced at a decent size.

The

expected Booklet is also promised,

but was not supplied with the review disk. Hopefully it

will give some social and historical background to the film

to help out the newcomers.

A

tricky one this. Assassination is an intricately

structured film that rewards the attentive and the patient,

but could prove hard to follow for those with their eyes

not glued to the subtitles or familiar with the background

to the story. The presentation is a bit below par, which

doesn't help, and the disk is not exactly flush with features.

But for its direction, the lead performances (including

old hand Tetsuro Tamba and Isao Kimura, who played the young

novice in Kurosawa's Seven Samurai), and

the narrative structure, it is definitely one that fans of

Japanese historical cinema should check out. But to paraphrase

a well known office poster, you don't need to know your

Japanese Samurai history to enjoy the film, but it certainly

helps.

*

Hachiro Kiyokawa even turns up as a character in the Japanese

Playstation 2 game Kengo 3, in which he

is required to form the Shinsengumi, the very event portrayed

in this film.

|