|

If you don't know the films of Aki Kaurismäki then

you could be in for a treat. The slight caution in my wording stems from the knowledge that his distinctive style certainly

doesn't work for everyone, although I've yet to meet someone

whose views I respect who doesn't delight in his singular

pairing of misery and deadpan hilarity. Maybe it's just

us. Certainly the audience for his films has remained closer

to cult than mainstream, even in his own country. In an

interview on Artificial Eye's DVD of his latest, Lights

in the Dusk, actress Maria Järvenhelmi

suggests that Finns themselves don't go and see his films

in large numbers because Kaurismäki gets a uncomfortably close to the truth about Finnish society and

attitudes. I can't personally vouch for this, but have

two Finnish friends who are jollier than anyone you'll encounter

in Kaurismäki's film world and who adore the director's

work, and they cheerfully testify to its accurate reflection of

both Finnish life and humour.

The

three films included here have been alternately referred

to, depending on the source, as The Underdog Trilogy and

The Workers Trilogy. Both titles are certainly appropriate, although

the first of these is a little imprecise, linking the titles

with a trait that is common to just about every lead character in

Kaurismäki's oeuvre. There's certainly the stamp of

the latter on the opening sequences of all three films,

which introduce us to the central character in their place

of work, focussing on the daily routine of rubbish collector

Nikander in Shadows in Paradise and on

the machinery that shapes and wraps the product for Iris's

inspection in The Match Factory Girl, while

the social commentary of Ariel is established

up front with Taisto helping to seal from the mine that he and his

colleagues have just been laid off from.

All

three films are clearly the work of the same director, sharing

his economically minimalist approach to storytelling, his

canny mix of traditional, blues and rock 'n' roll tunes

to both augment and counterpoint the mood of a scene, his

blend of observationally static shots with gentle dolly

work, the contribution of location and set dressing to the

mise-en-scène, and the way the gloom of the characters

does not downcast the film itself. The tone of the three

films may be similar, but the emphasis is different in each,

the deadpan comic exchanges in Shadows in Paradise

more poignantly undercut with the drama in Ariel,

while The Match Factory Girl paints its

comedy so dark that you be forgiven for missing it.

What

does unite the films and the characters is that they are

instantly and uniquely fascinating in a manner that defies

easy explanation. Certainly for someone who has grown increasingly

tired of being treated like a four-year-old by mainstream

cinema, which tends to loudly justify even the blatantly

obvious and handles emotional relationships as if following

strictly enforced stylistic guidelines, Kaurismäki's

imaginatively constructed and witty minimalism is a constant

delight. In common with Japanese actor/director

Kitano Takeshi, he can tell ten minutes of story with a single economical

shot or a perfectly timed edit, compressing a feature-length narrative into

little more than an hour. And there won't be a wasted moment

in it.

Shadows

in Paradise [Varjoja paratiisissa] was Kaurismäki's second feature, but even if the

only film of his you've seen is the recent Lights

in the Dusk, you'll instantly recognise this as

his work. The critical will find ammunition in this and

suggest that he has failed to progress or expand his horizons.

Of course you could also say that of Hitchcock and Ozu –

indeed it has been repeatedly claimed that the latter spent

his career essentially remaking the same film, but this is never

intended as a criticism. Ozu's films are often strikingly similar

to each other, but no-one else made films quite like Ozu,

and there's certainly no-one making them quite like Kaurismäki.

The

first half of this story's glum couple is garbage man

Nikander, whose regular co-worker tells him of his plans to start

his own refuse collection company – the bank is behind him,

he even has a location sorted, and he wants Nikander to come on board as

his foreman. It's a definite step up for Nikander and his

otherwise solitary and humdrum life, but wouldn't you know

it (this is a Kaurismäki film, after all), these best

laid plans die with their originator when he collapses on

the job with a heart attack. His dreams having been dashed, Nikander

recruits a new workmate, while two chance encounters land

him a date with unhappy supermarket cashier Ilona. It doesn't

go well – he takes her to a bingo hall – and she suggests

a parting of the ways. When she is laid off from her job,

however, she steals the firm's cash box and convinces

the bemused Nikander to drive her out of town.

Shadows

in Paradise is both an oddball love story and an

offbeat noir heist movie, complete with a revenge robbery,

a couple on the run and a moody femme fatale. Only here the robbery

nets little, the couple are don't go far, and although

definitely moody, there's nothing all that fatale about

our femme Ilona. Kaurismäki's ace in the hole here is actress

Kati Outinen, whose natural expression appears to be one

of misery bordering on tearful breakdown, a physical representation

of the director's trademark deadpan gloom. She's matched

all the way by Matti Pelonpää's deflated optimism

as Nikander, a man resigned to any fate that's handed out

to him but who still carries a small flame of hope for better

things. Little wonder that both actors became Kaurismäki regulars – Outinen was to appear in a further

nine films for the director (her role in the recent Lights

in the Dusk was effectively a cameo, but it still

counts), while Pelonpää was to feature in another

eight, plus two for the director's brother Mika.

Kaurismäki's distinctive style is on every frame of

the film, including his straight-faced humour, often in

stripped-down, functional exchanges that in mainstream western

movies would be emotional flashpoints. My favourite comes

when Nikander's co-worker outlines his plans for the new

company: "I've got a slogan already," he tells

Nikander with as much enthusiasm as he is prepared to muster.

"'Reliable garbage disposal since 1986'." "But

that's now," Nikander points out, which prompts the response,

"That's why it catches the eye."

Kaurismäki's

fifth feature is, despite some delightfully deadpan comedy

exchanges, one of his bleaker films, a downbeat drama of

misfortune built on a foundation of social commentary,

particularly regarding the changing employment prospects

in Finland in the late 1980s. This is signalled from the

opening scene, when a mine closure scatters the redundant

workforce to search for employment wherever they can find it. One of them,

Taisto, is given a Cadillac convertible by a colleague,

and after withdrawing his life savings, he too joins the work-hunt

exodus. This being a Kaurismäki film we don't expect

things to go that well, and it's no real surprise when Taisto

is knocked unconscious and robbed of his cash at the first

place he stops.

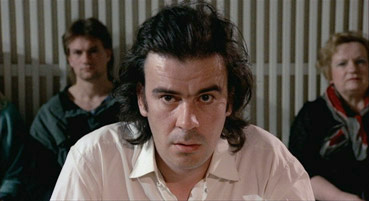

When

Taisto reaches the city he joins other desperate hopefuls

for a day's work at the docks, which pays enough for a bed

at the local mission hostel. A chance encounter hooks him

up with single mother Irmeli, who has to work long hours

in three different jobs to pay the bills. Taisto's own search

for regular work proves fruitless, and when he loses his hostel

bed he is forced to sell his car, his only

possession of worth. Chance again plays a hand when he spots

one of the men who robbed him – he avoids the man's knife,

but his attempt to retrieve his stolen money is interrupted

when he is overpowered and arrested by police, who have

mistaken him for the mugger. Prosecuted for the crime, he

is sent to jail for two years.

Even by Kaurismäki standards, Taisto is a bad luck

magnet, his run of misfortune almost as grim as that which

befalls Lukas Moodysson's Lilja in Lilja 4 Ever.

It's thankfully less punishing for the audience, due in

part to Taisto's uncomplaining acceptance of his fate (a typical

Kaurismäki trait), though the stone-faced deadpan humour

of his developing relationship with Irmeli counts for a

lot. Arriving at her flat at the end of the first date,

their unsmiling exchange is priceless:

| Irmeli: |

Thanks

for the evening. My first in a convertible. |

| Taisto: |

The

roof doesn't work. |

| Irmeli: |

I

know. It's dark. Want to come up? |

| Taisto: |

If

it's not too much trouble. |

| Irmeli: |

I've

only got coffee. |

| Taisto: |

Coffee's

fine. |

| Irmeli: |

I'm

divorced. |

| Taisto: |

Don't

let it get you down. |

| Irmeli: |

I've

got a kid, too. |

| Taisto: |

Even

better. We save time raising a family. |

| Irmeli: |

You

always this self-confident? |

| Taisto: |

This

is the first time. |

Taisto's

jail time has its own pleasures when his cell mate Mikkonen

turns out to be none other than Kaurismäki favourite

Matti Pellonpää, the friendship that develops

between the two giving the second half its structure and

the finale part of its emotional sting. The characters drive

the plot and there are no pauses for portraits of Finnish

prison life – others briefly enter the story only to move

Taisto, Mikkonen and Irmeli towards the final act.

Despite

boasting a level a humour you'll not find in The

Match Factory Girl, Ariel is definitely

the most emotionally affecting of the Underdog/Worker Trilogy.

There's an overriding reality here that ensures the mechanics

of fate that keep this oddly likeable family unit from coming

together really do hit home. As with The Match Factory

Girl, it's the self-interest of others that does

the most harm, but here it is balanced by Irmeli and Mikkonen's

unwavering loyalty and Taisto's determination to do right

by both. The destructive wild card is the system itself,

indifferent to the truth or the fate of those who fall victim

to its failings. It leads to an ending that is at the same

time both hopeful and sad (and set beguilingly to a Finnish

rendition of Somewhere Over the Rainbow), a final

comment by Kaurismäki on his own society, and the point

you'll have to reach to discover the significance of the

title.

I'm

not going to sit on the fence here – as far as I'm concerned, The Match Factory

Girl [Tulitikkutehtaan tyttö],

Aki Kaurismäki's sixth theatrical feature, is a minimalist

gem of a film, a simple story of a dour young woman and

the action she eventually takes to balance her reckoning

with her own unfortunate life and the self-centred behaviour of others. Fascinating in the way Kaurismäki's films

and characters just seem to be, it's in the final fifteen

minutes that it hits its home run, a consolidating and darkly

satisfying story climax on which an entire essay could be

written, but which I cannot discuss here without ruining

it's delicious sting for first-timers. Any reviewer who

does so should be hunted out and heartily slapped for their

insensitivity.

Kati

Outinen again lends her extraordinary facial unhappiness

to the role of Iris, the match factory girl of the title.

A silent and efficient worker, she hands most of her wages

over to her equally cheerless mother and stepfather, whom

she lives with and keeps house for. Her search for companionship

is not going well, but a change of image attracts the attentions

of Aame, whom she spends the night with. Hopes of a developing

romance are soon dashed by Aame's indifference to her attentions

and annoyance at her persistence, but the discovery that

she is pregnant proves a turning point for her and her relationship

with those around her.

Kaurismäki's

specific brand of minimalism is extended here to a pared-to-the-bone

approach to dialogue, which very effectively emphasises

Iris's isolation and loneliness. We're 23 minutes in before

she speaks to anyone, while her fractured relationship with

her parents is highlighted by the first on-screen word spoken

to her by her stepfather, who slaps her face and calls her

a whore after she buys a new dress with wage money that is usually

handed to them.

This

non-verbal approach does produce one of the few light moments,

when Aame agrees to take Iris out and finds himself in the

seat-grindingly uncomfortable company of her parents while

she goes off to get ready for their date. It's a rare chance to smile

in an otherwise downbeat but consistently involving and

touching portrait of life suffocated by circumstance and

punished by the self-interest of others. It's hard to imagine

Iris played by anyone but Outinen, the brief moments when

a smile breaks her otherwise unbroken expression of gloom

betraying the hope that still flickers behind her grim façade.

It's

in the final scenes, those ones I prmised not talk about in detail,

that this galvanises her into action. It may not be the

romantic idyll she dreams of, but in the heartless world

in which she finds herself, it can't help but seem both

logical and perversely positive. It's here that you'll find

the deadpan humour that is largely suppressed in the build-up,

though rarely if ever in Kaurismäki's work will you

find it painted this black.

A

barrel of laughs it may not be, but The Match Factory

Girl tells its story with captivating cinematic

economy and an affection for its forlorn central character

that binds us to her from her first appearance. It's a bond

not just of sympathy but empathy, a recognition of darker

moments in our own lives and the cruelty we may have endured,

however brief or unintended, from those we regard as close

to us.

Of

the three films in this first set, the only one I have seen

on DVD before is The Match Factory Girl,

a Finnish disc whose transfer quality I was impressed with.

It would appear that Artificial Eye have sourced their disc

from the same original, as the anamorphic 1.85:1 picture

here is a dead ringer for the one on the Finnish DVD, and

that's fine by me. The other two films are similarly well

presented – the colour has an occasional and probably intentional

pastel bias, while contrast and black levels are bang on.

Film grain is sometimes visible and the occasional bit of

dust remains, but the level of detail is often first rate.

There is some slight flickering in a couple of scenes and

digital purists may be a bit miffed to see reel change markers

still present, but otherwise I have no complaints.

All

three films have Dolby stereo 2.0 tracks and they are some

of the best I've heard in a long while, vividly clear mixes

with strikingly full sound and tonal range. Frontal separation

is precise and well used.

None.

A bit of a shame, as a bit of background on each of the

films would have been nice, ideally from Kaurismäki

himself, but as far as I remember the Finnish discs were

also film-only affairs.

A

pity about the lack of extra features, but it really doesn't

matter. You still get three terrific films from one of world

cinema's most distinctive talents, all boasting fine transfers

and soundtracks. The first of four such collections from

Artificial Eye, collectively they should represent a long

overdue and most welcome treat. Warmly recommended.

|