|

I might as well come clean and admit that I don't believe in the concept of an afterlife. It would be nice if I did, to be comforted by an assurance that we really do live forever, but I've never bought into it and am unlikely to do so now. If you do, good luck to you, but I don't want to hear about it. I've had more than my share of discussions and arguments over a subject that is required, by its very nature, to be a matter of faith rather than documented fact.

In movies – well, non-horror movies at least – the afterlife has tended to be either alluded to rather than shown, or presented respectfully with a mixture of grandeur and simplicity, a location designed to both inspire awe and yet symbolise the everlasting tranquility promised by the religion in question. While visions of hell usually owe a debt to Dante, Heaven tends to be bright, big, sparsely furnished and non-specific enough in design to avoid dividing architectural opinion. Of course, CGI has allowed for a more elaborate vision of where good people go when they die, typified by the horrible overdose of renaissance imagery and new age claptrap that was Vincent Ward's When Dreams May Come. Sorry, but for the Outsider crew the most endearing movie Heaven by far remains the starved-of-Technicolor celestial courtroom in Powell and Pressburger's A Matter of Life and Death.

The cinematic interpretations may vary, but I can pretty much guarantee you won't have seen a vision of what lies beyond quite like the one in Koreeda Hirokazu's After Life. And if the very idea of a film set in the hereafter conjures up images of big white rooms and winged angles and fluffy clouds, you really are in for a surprise. Here the newly deceased spend a week at what is effectively a preparation centre for eternity, where sympathetic counsellors help them select the most meaningful and precious moment from their life, which is then recreated on film and screened for them to relive, immediately after which they are transported to spend eternity in the company of just that one, perfect moment. Come on, aren't you just a little bit intrigued by that?

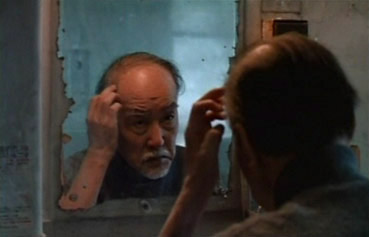

But that's not all. This gateway to eternity has none of the scale and clerical hyper-efficiency of Powell and Pressburger's gargantuan heavenly filing room and resembles instead a run-down primary school after years of crippling budget cuts, complete with tattered walls and fittings, unheated wash water and an electricity supply that shorts out the moment someone uses a hairdryer. The staff are similarly stripped of the traditional majesty, being ordinary clerks with everyday interests and concerns, diligent workers who discuss their case loads at team meetings and share stories over a cup of Earl Grey, but who are as prone to frustration, desire and nostalgia as their clients.

Now I'm fully aware of how odd this is going to sound, given that we're talking about a film set entirely in a highly speculative post-mortal existence, but the most disarming and enchanting aspect of After Life is its sense of reality. This is particularly evident in the 22 visitors whose journey from arrival to eventual departure the film follows during the course of its running time. In the interviews that occupy the film's first third, they talk almost straight to camera with a matter-of-fact honesty that suggests the performers are discussing their own lives rather than those of their characters. This is enhanced by Koreeda's quasi-documentary approach, which proves particularly effective here and in the final half-hour, once the memories have been chosen and the staff engage in the task of recreating them, working directly with their clients to locate just the right sort of light aircraft or dress or dance step. There are whole sequences here, as with the woman who demonstrates the making of rice balls in a bamboo grove for the gathered crew, or the man who sits in the mocked-up plane and marvels at its realism, where you would swear you are watching a documentary rather than a fictional feature.

Excellent though the actors playing the counsellors are, it's the extraordinary naturalism of their various clients that give the film its unique and captivating poetry. Our connection to them is triggered by memories, attitudes, joys and disappointments that are similar to those from our own lives and those close to us.

A cross-section of age and backgrounds is represented here: the middle-aged woman hanging on to her lost youth, reflecting on a love life of repeated let-downs; the similarly aged man who confidently affirms his masculinity through tales of sexual conquests; the older woman who smiles at the memory of a husband she dearly misses; the man for whom life was so regretful that he welcomes the thought of its erasure from memory; the young girl who believes that the high point of her life so far was a trip to Disneyland, until prompted to look deeper by her female counsellor. One uncooperative youth, Iseya, steadfastly refuses to select a memory, an act of rebellion that is eventually shown to have its own consequences, while the elderly Watanabe finds himself unable to select a special moment from a life that he regards as consistently unremarkable. Watanabe's story is particularly intriguing, his search for an appropriate moment aided by a vast library of VHS tapes of his life (one of many lovely low-tech touches – they even have to be ordered by phone from another, unspecified facility), which he watches with regret for the things he never did, while the uneasiness of his counsellor Mochizuki is eventually revealed to be much more than just simple frustration at his indecision.

Perhaps the most beguiling character of all is Nishimura, an old woman so lost in her own world that her counsellor Kawashima (played by Kitano Takeshi favourite Terajima Susumu) believes that she found her special moment while she was still alive and has been living there ever since. It's she that provides the film with its most warmly humorous scene, as objects she has gathered from the garden are placed methodically on the table in front of her, while the patient Kawashima fruitlessly prompts her for a verbal response. Later, her simple but unexpected gift to her counsellor and the contented smile that follows gives rise to a moment of extraordinary but unforced poignancy, one of a number that occur as the visitors relive the often disarmingly simple moments they have selected to take with them.

There's so much more to talk about with this extraordinary film, but its pleasures are best experienced rather than read about. After Life is a simple but genuinely beautiful work, marvellously but oh-so-subtly realised and the complete flipside of the false emotion and theatrical drama that would doubtless dominate any Hollywood take on the same story (and please, let this never happen). It's certainly possible to question the logic of the centre's workings, but this seems a little churlish given that its form and even existence is speculative in the first place. This is, after all, not a film about death or faith or the nature of the next world, but about life and the beauty of even its smallest moments. In this respect the original Japanese title, Wandarufu Raifu – literally Wonderful Life – is far more appropriate and meaningful (the change was no doubt devised to avoid confusion with Frank Capra's Christmas perennial It's a Wonderful Life), as watching the film can't help but remind you that life is indeed a sometimes wonderful and precious thing. Inevitably you're inevitably left pondering the question asked of all who pass through the centre: what moment from your own life would you choose to take with you for all eternity?

The letterboxed 1.66:1 transfer here is serviceable rather than sparkling. There's a softness to the image that loses fine detail in wider shots and visible grain in places, but the contrast is generally good and black levels are solid enough. The running time, occasional movement stutters and some jagged edges on diagonals give this away as an NTSC to PAL transfer, something the American spelling on the fixed English subtitles seems to confirm.

The Dolby mono 2.0 soundtrack is clear and free of distortion, and that's what counts in a film driven by dialogue and lacking a traditional score (the only music is daigetic).

None on the review disc. Apparently the release disc includes a photo gallery.

After Life, or rather Wandarufu Raifu, inevitably won't work for everyone, but it's a film I adore and feel no inclination to be impartial about. The concept may seem as fanciful as any you'll find for a post-mortal existence, but the deliberately and recognisably drab setting and realistic handling give it a curious if fleeting sense of plausibility. Either way, it's a film I've watched many times and have been gently spellbound on each viewing. It's great to see it out on UK DVD at last, I just wish we could have had a PAL transfer to show the film at its best.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for names throughout this review.

|