|

As is my way, I'll come clean on my prejudices and state up front that I detest TV talent shows of any description, particularly those of the so-called Reality Television variety, where viewers are encouraged to be as catty in their opinions as the vacuous judges. While they may well discover the odd true talent, they largely specialise in manufacturing a shallow approximation of the same – The X-Factor in particular is a self-fulfilling prophecy in which acts are whittled down through a process of humiliation and elimination to a single pretty young face that can be used to sell a banal reworking of any old tune they are encouraged to record, in order to sell it to a celebrity-addicted audience that will buy anything as long as it's been on TV. What a joy it was to watch this multi-million pound machine sabotaged by a cost-free Facebook campaign and a song that actually deserved the Christmas number one spot. Rage Against the Machine indeed.

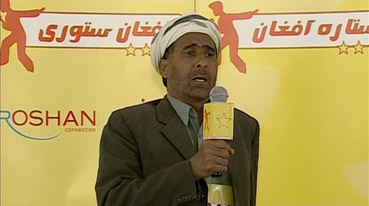

It says something about how we tend to perceive modern Afghanistan that the very suggestion of an Afghan Pop Idol style talent show will usually prompt expressions of smiling surprise and even disbelief. But why not? With televisions now freely available and the Taliban-imposed ban on public singing and dancing lifted, Afghans are free to pursue this same shallow aspects of an open society as the rest of us. And on the surface at least, the TV talent show from which Havana Marking's fascinating, smartly shot and edited documentary borrows its title is every bit as superficial as any of its western equivalents, one in which youth, good looks and a clean public image appear to be every bit as important as the ability to hold a tune. Even the audition process has a familiar ring, with judges wincing as songs are murdered by tuneless hopefuls in search of their fifteen minutes of musical infamy.

Having introduced the programme and its energetic creator/host Daoud Sediqi (a man who made a living in Taliban times by smuggling, repairing and selling TVs), the film then focuses on four contestants – two male, two female – who are destined to survive the early eliminations and go head-to-head for the $1,000 prize. Representing the men is good-looking young wannabe pop star Rafi and classically trained singer Hammeed, while for the women there's Kandahar-born traditionalist Lima, and 21-year-old Setara, an open-minded progressive with a fondness for makeup and fashionable clothing. Collectively, their stories paint a diverse picture of the changing face of the new Afghanistan, one where traditional and religious values appear to be giving way to a more open attitude to gender equality and the cultural influence of the West.

The show's considerable popularity is evident at every turn: young boys run from field work to catch that evening's episode; troops are used to control excited crowds as they jostle to join the studio audience; and as a family of devoted fans argue over which candidate they like the most, the eldest daughter rigs up a large makeshift TV aerial on the roof, while her young sister uses dolls to stage her own small version of the show. For its fans, the programme encapsulates the new freedoms of post-Taliban Afghan society and celebrates them on a public stage, giving ordinary citizens the opportunity to chase a dream and transforming the successful into figures of public adulation. For many younger viewers, participation in the mobile phone vote is their first direct experience of the democratic process, a system that the wealthy have already learned how to abuse – an unconfirmed report suggests that one individual has purchased 30,000 sim cards to ensure that his contestant of choice is voted through to the next round. There's also a sense that the show has a communally unifying role, crossing ethnic boundaries, bridging the generation gap, and providing a focus for social gatherings and enthusiastic discussion.

As the story unfolds, however, the lingering legacy of years of religious oppression become worryingly evident. Daoud receives an official warning from the Ministry for Information and Culture for corrupting the minds of his audience, the influential Ullema Council of Islamic Scholars condemns the show as immoral, and Taliban activists threaten to target mobile phone networks. But the real trigger for Islamic fundamentalist anger occurs when Setara, caught up in the performance of her final song, dances and removes her head scarf in front of the TV cameras. Now we're not talking wild breakdancing moves here, but the sort of gentle rhythmic shuffle you might do if singing to yourself while dressing or doing your hair, but it's a move that startles her fellow contestants and provokes widespread shock and outrage. Setara is instantly labelled a loose woman and is publicly condemned for this "insult and degradation" by the ex-governor of her home city of Herat, one of whose young citizens claims sincerely that she deserves to be killed. The death threats that follow force Setara to flee her home and go into hiding, returning later in secret to visit her distraught family amidst rumours that she has already been murdered.

Yet in spite of this there's an underlying optimism for changing times, in Setara's defiant resilience, in the female audience members who cheerfully dispense with their head scarves at the final show, and in Daoud's curt dismissal of the relevance of the country's former rulers in present day Afghanistan: "I'm not scared of the Taliban," he defiantly remarks, "Don't talk about them. They're not important." Small pockets of rebellion, perhaps, but a flavour how rapidly and drastically a society can be transformed is provided by the film's most unexpectedly startling image, archive footage a 1980s Kabul that looks more like a European city than our common perception of the Afghan capital, a place where women wore western style clothing and hairstyles, and walked in public with their heads uncovered. And they sang. Now, after years in the forbidden zone, music is being enjoyed and celebrated and is emerging as a key force for liberation and change, a view summed up by the young boy at the film's start who says, "If there were no music, the world would be silent."

Shot on HD on what looks like the Sony HVR-Z1E, a low-cost HD camcorder that for a while was a firm favourite with professionals working on a limited budget, the image here is clean, with well balanced contrast and naturalistic colours, the earthy look to some of the scenes reflecting the surroundings, clothing and lighting conditions. Sharpness and detail are good, but lack the eye-catching crispness of high-end HD and HDCAM material, though this tends to work well for the documentary format, giving the visuals a similar feel to popular documentary formats like DVCAM and low grain 16mm. The transfer is framed 1.78:1 and is anamorphically enhanced.

The Dolby 2.0 stereo soundtrack scores on clarity and range, with the music coming off best, especially if you feed the bass is through the subwoofer. Dialogue is always audible, even when battling with background noise, though the fixed subtitles have erred on the side of caution to provide clarification on spoken English when individual words (names of places and people are favourites) might not be completely clear.

Interview with Havana Marking (11:13)

The director talks about the inspiration for the project, the problems of filming in Afghanistan, selecting which characters to focus on, how things have changed since the film was made, her working relationship with cameraman Phil Stebbing, the two subsequent films she has made in the country, and her continuing fears for Setara's safety.

Trailer (2:54)

A simple but quite seductive trailer that, like the film, undercuts the energy and upbeat nature of the show itself with the story's darker side.

A compelling portrait of modern Afghanistan that gets past the news headlines to paint a revealing picture of the optimism, humour and sometimes defiant energy of its younger citizens, but also provides a sobering reminder of the risks of free expression in a society where religion and its intolerant exponents still hold sway. The picture and sound on Dogwoof's disc are every bits as good as they were in the cinema (as far as I am aware the film is available for digital projection only and has never been transferred to 35mm), and while the extras are little slim, the interview with Havana Marking is still welcome. Recommended.

|