|

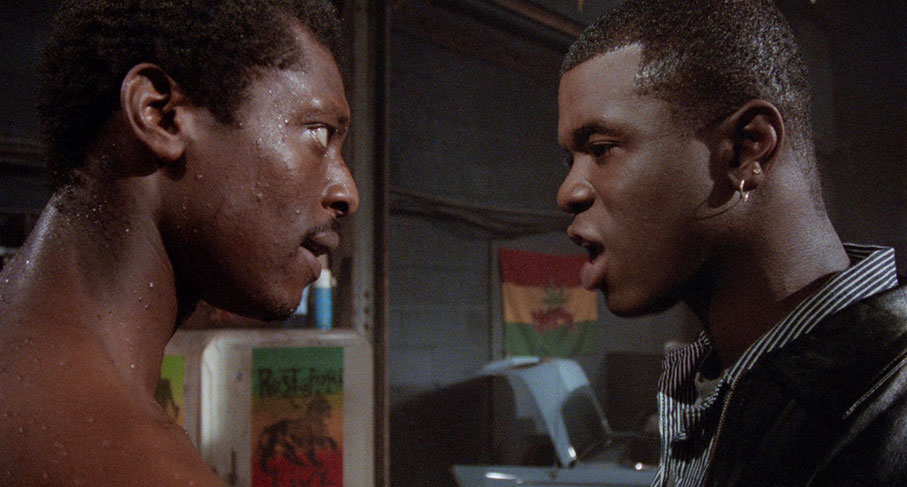

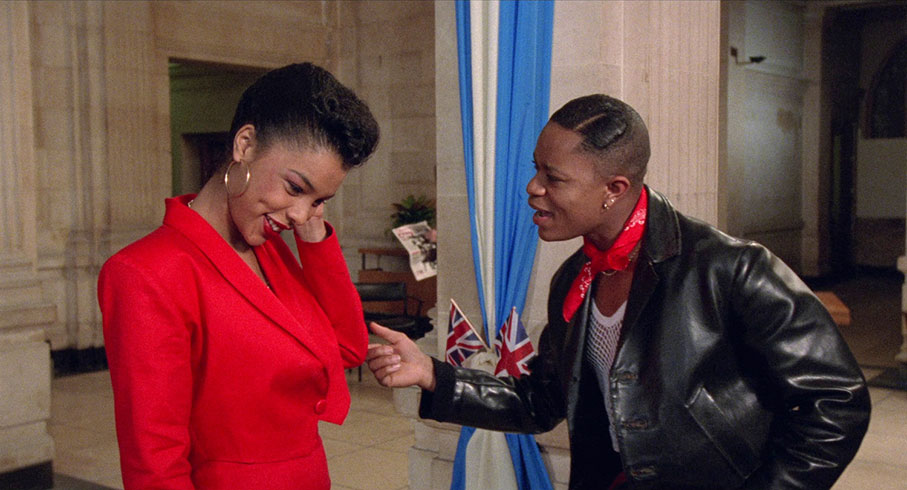

It's the summer of 1977. The Queen is about to celebrate her silver jubilee, but not everyone thinks that there is something to celebrate. Out of this disaffection comes the punk, soul and funk scenes. A small part of this are mixed-race Chris (Valentine Nonyela) and black Caz (Mo Sesay), two friends who run a pirate soul/funk radio station out of a friend's garage. Caz, who is gay, has a white boyfriend, Billibud (Jason Durr), while Chris, trying to break into the music industry, meets Tracy (Sophie Okonedo). Meanwhile, the murder of a gay black man while out cruising causes tensions in the community.

Sir Isaac Julien, born 1960, was trained as a visual artist and he still is one, as well as a filmmaker, with some of his filmmaking being gallery installation pieces, most recently Once Again… (Statues Never Die) in 2022. He was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2001 and was knighted in 2022 for services to diversity and inclusion in art. His first films, such as the mid-length drama-documentary Looking for Langston, were aimed at arthouse audiences, and much of his work since – including further documentaries Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask, Baadasssss Cinema and Derek, the last-named his tribute to the late and highly influential film director Jarman – has been so aimed. Young Soul Rebels however enjoyed a somewhat larger budget (relatively that is, compared to other black-themed films of the time) and a wider release than it might otherwise have had, and it gained a wider release than most BFI (co-)productions. Given that, there seems to have been an effort to widen the film's appeal. The script (by Paul Hallam, Derrick Saldaan McClintock and Julien) uses a thriller plot – the murder investigation, and in particular a vital tape recording – as a line to hang on what are clearly the film's real interests and angles: its evocation of the period and its politics, racial, sexual and social. As such the film feels a little compromised, if understandably so, and it is also flawed by some weak performances and some plot contrivances. However, it has an energy and attitude that's hard to deny and makes the film hold up well enough today. It also has a fine soundtrack, a mixture of punk, funk and gay disco, featuring among others X-Ray Spex, Parliament and Sylvester.

The two young stars, Nonyela and Sesay, do well enough, and have continued their acting careers since. Nonyela continued until a role in Casino Royale in 2006 but since then made a short film in 2020. Mo Sesay is still acting to this day. Young Soul Rebels was the cinema debut for both, though they had acted on television beforehand. However, also in her debut, was a real star in the making – Sophie Okonedo, who would go on to be Oscar-nominated for Hotel Rwanda. Frances Barber, a frequent face in British indies in the late 1980s, has less to do in a smallish role as Chris's mother. Nina Kellgren's camerawork is another plus: she has continued to collaborate with Julien, most recently on Derek. With the Welsh-language film Solomon and Gaenor (1999), she became the first British woman to shoot an Academy Award-nominated film and the second woman from any country to shoot a Best Foreign-language Film nominee. You can see Julien's artist's eye at work, though to his credit, the effect is not as studied as it can be in other films made by artists. Young Soul Rebels premiered at the 1991 Cannes Festival in Critics’ Week and won the SACD Prize for its screenplay, before its UK cinema release on 9 August 1991.

Being set during the 1977 Silver Jubilee (with a voiceover from Queen Elizabeth towards the end), the film was a period piece at the time it was made. Now, with that Jubilee in the distant past and the Golden and Diamond Jubilees fading memories, and the Platinum Jubilee soon to join them, Young Soul Rebels is now a double period piece. Watching it now takes us back to a particular period in British independent filmmaking, as the film itself comments on its then past of fourteen years previously. Julien’s film does capture a time and place and does so quite well. Sadly and perhaps inevitably, many of its concerns are still relevant.

Originally released by the BFI on DVD in 2009, Young Soul Rebels gets a Blu-ray upgrade, the disc encoded for Region B only. The film had an 18 certificate originally but is now a 15.

The film was shot in 35mm and the Blu-ray transfer is from a 4K scan and remaster from the original negative, in the intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. There is certainly grain to be had, particularly in the shots of the twilit London skyline during the opening credits. The colours are strong, with the frequent reds particularly noticeable, and shadow detail is fine.

Young Soul Rebels was made two or three years too early for digital soundtracks, and it was released in cinemas with a Dolby SR sound mix. The Blu-ray has a LPCM 2.0 soundtrack, which plays in surround. It's a rich and full-sounding mix, and the music (the main beneficiary of the surround speakers) sounds fine. In addition, the disc has an audio-descriptive track, also in LPCM 2.0. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on the feature only.

Commentary with Sir Isaac Julien and Nina Kellgren, moderated by William Fowler

BFI curator Fowler begins by quoting a very surprising positive review from the Daily Mail, given that the newspaper would normally have loathed this film on sight. Julien and Kellgren talk about the film’s colour scheme, such as purple (from the “soul” in the title onwards) signifying noir. Julien says that the heightened colour was deliberate, and something of a reaction to his and Kellgren’s previous collaboration Looking for Langston, which had been shot in black and white. Kellgren’s contributions are mainly technical, even down to the film stocks used. She also mentions that this film intentionally has its black actors well-lit, which was a rarity at the time. Julien sees the film as a 90s view of its 70s subject matter, and intended the film as entertainment as much as social message. Regarding the film’s gay angle (at a time of anti-gay backlash, with Section 28 on the statute books and the effects of AIDS still prevalent), Kellgren says that they shot the one sex scene in the film in a single take, partly so that any censor could not cut it unless they removed it entirely. (It was the stated reason for the 18 certificate the film carried at the time.) This is a useful commentary track which fills in a few details which may not be apparent from the film itself.

Press materials and original script

Over 200 pages, we get the original press book, an invitation to the charity premiere (followed by a party) and then the entire script. This is a post-production script, so is divided into reels (back in the pre-digital-projection days, for the youngsters out there) and has timings for dialogue, music and sound effects spots.

Theatrical trailer (2:17)

This is the only on-disc extra carried over from the 2009 DVD release. It’s a trailer which tries to sell the film from several different angles: the thriller plot, the music, some comedy, the gay element (both bare-chested male leads zipping up tight pairs of trousers) and a lingering shot of Sophie Okonedo as her credit comes up for those in the potential audience attracted to women. It’s a 15-certificate trailer due largely to an incidental “fuck off” and a reference to weed of the non-garden-pest variety.

Image gallery (8:07)

A self-navigating gallery including production and publicity stills and lobby cards, several in black and white.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing only, runs to thirty-two pages. The main essay, new to this edition, is by Alex Ramon, begins by discussing the critical coverage of the time, which bracketed the film with the wave of black cinema coming from the US at the time. Ramon instead locates Young Soul Rebels in a line of British films dealing with transgressive interracial relationships, a short line beginning in the 1950s with social-problem films such as Sapphire (1959) and continuing to this film’s near-contemporaries My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987), both written by Hanif Kureishi. There’s also a link to the then just as short line of British gay films, as Paul Hallam had written Nighthawks (1978). Ramon sees the film as a hybrid of influences, but also concludes that the promised new wave of black British films never really happened.

The remaining essays are carried forward from the BFI’s 2009 DVD release. Stephen Bourne remembers the disaffection felt in many quarters at the nationalism, at times jingoism, of the Silver Jubilee celebrations. He acknowledges that Young Soul Rebels was aimed at a wider commercial audience than Julien’s earlier (and later) work but it wasn’t successful enough and faced something of a backlash from critics, Alexander Walker being particularly singled out. Next up is a long extract from Diary of a Young Soul Rebel, cowritten by Julien and Colin McCabe, published in 1991 to coincide with the film’s release. In a preface, Julien concedes that his film is now seen as an archival document, as a 90s view of the 70s, and quotes Mica Paris’s song on the film’s soundtrack. He contrasts the music scene of the time with the backlash led by the far right, in those days the National Front. Although he sees documentary elements in his film, his main motivation was entertainment, as working-class communities were not the audience for documentaries about their lives.

The booklet continues with full film credits and a three-page biography of Julien, written in 2009 by B. Ruby Rich, updated by James Keith. There are notes on the extras and plenty of stills.

Despite some flaws, Young Soul Rebels stands up well. It’s now something of a time capsule, of the kinds of films that were being made at the time, as well as a look back at the period when it was set. The BFI’s Blu-ray presents the film well, with one useful new extra in the form of its commentary.

|