| “We’ve all got honest jobs. That’s more difficult than drawing a knife.” |

| Sound advice from a former yakuza in Violent Streets |

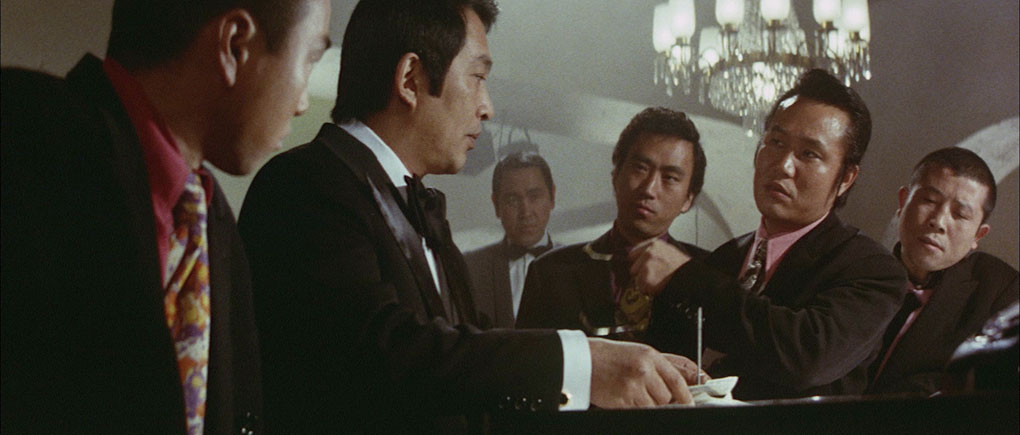

I don’t know about you, but when I sit down to watch a 1970s Japanese yakuza movie, one thing I don’t expect to see and hear under the opening titles is a fiery flamenco number being performed by a talented trio of professional Spanish musicians. So hang on a second, does this presumably very Japanese story begin over in Spain? A tale, perhaps, of the intercontinental nature of yakuza business of the day? As it turns out, no. It's quickly revealed that we’re in Tōkyō’s famed Ginza district, and the performers are the house musicians of a Spanish-themed nightclub named The Madrid run by the stone-faced Egawa (Andō Noboru). As the group beings begin its second number, Egawa is alerted to a problem at one of the tables by his associate, Mochizuki (Murota Hideo). “I bet they’re associated with the Togiku Group,” Mochizuki opines, and from their hairstyles, loud neckties and aggressive behaviour, it seems likely that they are yakuza. It’s clear that Egawa has had to deal with such customers before, and in that politely subservient Japanese way, he unreservedly apologises to them and places the fault for the upset squarely on his own employee. One of the men then deliberately pours beer onto his clothing and demands to know who’s going to pay for his now ruined European jacket. Once again, Egawa remains calm and conciliatory, and agrees to pay whatever sum the man demands. He then leads them to a corner of the bar and begins pulling single ¥10,000 notes from his pocket and theatrically sticking them on a receipt spike located at the end of the bar. The yakuza are clearly not impressed with this emotionless show of contempt, but just as European Suit Boy is about to explode, Egawa grabs the receipt spike and rams it into his forehead. When one of his associates tries to intervene, Egawa slams him against the wall and smashes a telephone receiver over his head, leaving him screaming and bleeding profusely. He then walks back over to European Suit Boy and says to him calmly, “Thank you. Please come again.” All the while, the flamenco performers carry on as if playing in a different universe. It’s an economic introduction to the man around whom the film is set to revolve, his no-nonsense toughness and complete disregard for the likely criminal status of the disruptive guests – coupled with an angry and very visible facial scar (more on that in a minute) – suggesting a man who is either so hard that he is not remotely intimidated by yakuza goons, or…

A short while later, we are clued into the fact that Egawa was also once a yakuza with the Togiku family, but that following some unspecified incident that resulted in jail time, he was allowed to retire and was given The Madrid as a parting gift. But as suave and ambitious Togiku lieutenant Yakazi (Kobayashi Akira) calmly informs him, the family now wants the bar back and is prepared to pay him a handsome sum for its return. He also reveals that a rival group named The Western Alliance of Kansai (the subtitles have it as Ōsaka rather than Kansai, opting for a city that most in the West will have heard of instead of the region in which it is located) is making moves to steal local territory from the Togiku family, which prompts Egawa to suggest, “And you don’t want a misfit who left the family sitting in the middle of Ginza.” Yakazi coolly refutes this, also denying that they have been trying to intimidate Egawa by sending thugs to the bar to cause trouble. “The Togiku family is no longer a group of yakuza like when you were in,” Yakazi informs him. “It’s a legitimate company named Togiku Corporations Ltd. There’s no need for us to resort to such petty means. We can find legal ways to kick you out if we want to.” This paints a concise picture of the scale of the problem facing Egawa, who makes it clear that he intends to stay put, no matter how much the family offers. It also serves as an still-pertinent reminder of who the real criminals are in the modern corporate world...

Before the conversation between the two men can proceed further, Yakazi is called away on an urgent matter, leaving Egawa to deal with his drunken lush of a girlfriend, Yuko (Akaza Miyoko). When he coldly brushes her off, she chides him for still pining after his former love, who ended up marrying Togiku boss Gohara when Egawa was in jail. He responds by dragging her into the back room for some initially aggressive but ultimately consensual sex, which is snappily intercut with the flamenco performance taking place just a short distance away. Yakazi, meanwhile, is over at a TV studio in which they have a financial stake, from where young and popular singer Minami (played by real-life singer Nakatsugawa Minami) has been kidnapped. The Togiku family has spent a considerable sum setting up and grooming Minami, and the blame is for her kidnapping is immediately laid at the door of rival company Star Productions, which is known to be affiliated to the Western Alliance. When the family bosses meet to discuss their next move, they receive a phone call from the kidnappers, who dodge the question of who they might be working for and demand a ransom of ¥100 million for Minami’s safe return. As soon as they put down the phone, the kidnappers delight in the news that the Togiku bosses think this is the work of the Western Alliance, and especially the possibility that a war between the Tōkyō and Kansai groups is about to kick off. It’s then that we discover that they are being led by Egawa’s nightclub associate and fellow former yakuza Mochizuki, who is especially hopeful that the kidnapping will be the final straw that prompts the now corporate Togiku family to once again take up arms against its enemies.

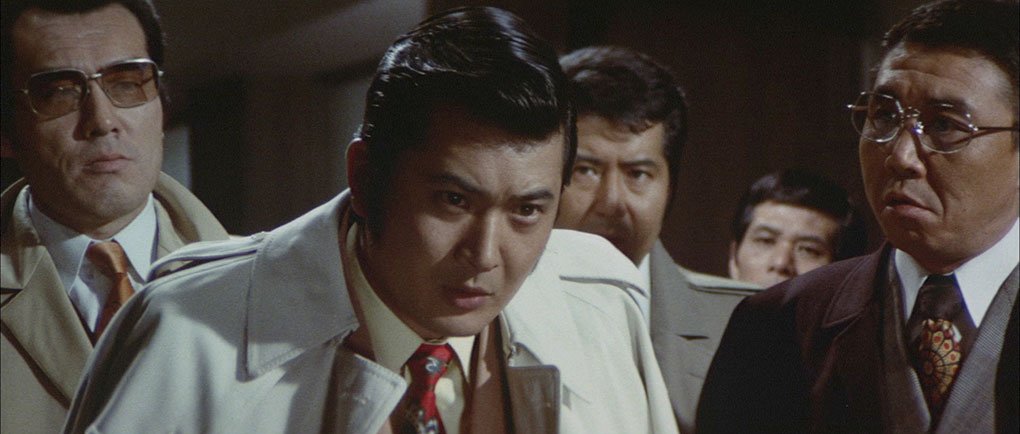

The 1974 Violent Streets (a literal translation of the Japanese original, Bōryoku gai, and also known in the West as Violent City) was far from the first film to make frustration at the waning of Japan’s warrior spirit an element of its subtext, but director and co-screenwriter (with Kakefuda Masahiro and Nakajima Nobuaki) Gosha Hideo is quick to bring it to the fore here, employing it to slyly comment on the corporatisation of Japan and the loss of individual identity. This is at its most evident after Yakazi and his men impulsively trash the offices of Star Productions, and Yakazi is berated for his actions by his superiors. As they sit around a boardroom table like the corporate executives they have effectively become, angrily expressing their concern about the reputational damage such actions could do to the Togiku Corporation, Yakazi casually paces the room, expressing his bemusement at their reticence to react to an outrage that I’ve tactfully not revealed the full details of here. Surprisingly, perhaps, Egawa seems to share the Togiku bosses’ reluctance to take up arms, albeit for different reasons. Badgered to revive the Egawa family by former comrades Mochizuki and Hama (Natsuyagi Isao), he rejects the notion as impractical, although his faltering expression does suggest a degree of uncertainty on this score. The pressure is upped when the Togiku group begins recruiting for a war that they believe may now be inevitable, and Yakazi is sent to request that Egawa return to the fold, the suggestion being that he will be allowed to keep The Madrid if he agrees to do so. It’s an offer that you suspect Egawa might be tempted to accept if the Togiku family was not under the rule of Gohara, a man he clearly holds in contempt as a leader and still despises for effectively stealing his girl.

That Egawa will eventually be given reason to take up arms again is something of a subgenre inevitability, but it’s a process that advances in small but sometimes significant steps. Things really kick off when four members of the gang that that kidnapped Minami are hunted down and killed by an oddball pair of assassins (more on them in a minute), and one of the remaining three, a local punk named Haruo (Koike Asao), is picked up and tortured for information by the Togiku boys. It turns out he’s the brother of Egawa’s current girlfriend Yuko, who then pleads with him to intervene and secure her troublesome sibling’s freedom. When Egawa unexpectedly sucks up his pride and pays Gohara a visit to humbly request that they hand Haruo over to him, he is treated with mocking disrespect by his hosts, and further humiliated when the woman who left him for Gohara enters the room in a subservient role to serve them tea. The look she passes Egawa is telling, as is his responsive breaking of eye contact and subsequent refusal to acknowledge her complimentary comments as he leaves.

Violent Streets hit Japanese cinemas just over a year after Fukasaku Kinji’s genre-defining Battles Without Honour and Humanity [Jingi naki tatakai], which effectively kickstarted a second wave of yakuza thrillers known as the jitsuroku eiga, or ‘actual record films’. Gosha’s movie eschews the documentary edginess of Fukasaku’s thrilling style-setter (which quickly grew into a series of five movies), instead opting to tell its story in a more traditional manner, with the locked-down camera, smoothly executed movements, and only occasional switches to handheld camerawork when the action hots up. The film also emphatically distances itself from the ‘based on a true story’ hook of Fukasaku's movie by stating in an up-front caption that the tale it tells is pure fiction and in no way inspired by actual events. If this seems like an unnecessary addition – the vast majority of screen dramas are fictional creations, after all – the reason apparently lies in the casting of Andō Noboru, who before becoming an actor was a real-life yakuza boss with his own family in the Shibuya district of Tōkyō, a career that came to an end when he landed a six year prison sentence for sending a hitman to shoot businessman Yokoi Hideki over an owed debt and a personal insult. Think about that, a former yakuza who crossed the line and did jail time, then on his release found some success in the entertainment business – with parallels like that, it’s no wonder that the filmmakers opted to err on the side of caution. And this is not stunt casting – Andō had already proved his worth as an actor by this point and is an excellent fit here, often sullenly inexpressive but in a manner that really works for his character, while the real-life battle scar that runs from the corner of his mouth to his ear says as much about his character as the no-nonsense manner in which he deals with troublesome customers.

On the surface, at least, Violent Streets plays initially by the 70s yakuza movie playbook, and in that respect it delivers all of the expected goods. The violence is brutal, bloody, and often realistically scrappy, and there’s a quota or sex and nudity to earn the film its upmarket exploitation badge. But in other respects it breaks with tradition, and its distinctive and occasionally offbeat (if backstory-light) characters really do help it stand out from the crowd. The insular Egawa certainly makes for an intriguing protagonist, his lack of surface emotion making it hard to predict just what his intentions are or what he might do next, his true feelings only occasionally flickering momentarily to the surface, at least while he resists the pull to return to his old life during the film’s first half. Every bit as engaging is Kobayashi Akira as Yakazi, an effortlessly smooth and smart-dressing old-school yakuza who just doesn’t gel with the new corporate model being shaped by Gohara. For the most part, he’s happy to sit on the side-lines while his minions dish out the beatings, but when a group of rival yakuza starts a ruckus that disturbs his drinking, he takes them all on and gives them a sound beating, suffering only a single injury to his hand in the process. Popular actor Tanba Tetsurō sits high on the cast list as the head of the Western Alliance, but he is only on screen for a few minutes in a couple of scenes in what really qualifies as more of a cameo appearance. The same could also be said for Sugawara Bunta’s brief role as underworld gunmaker Tatsu, but his cheerful eccentricity ensures that he makes an impression, as he jovially blackmails his way into joining Egawa on a shootout that he largely ignores to eat a sandwich and listen to music, popping up every now and again to fire a handily timed shot. Leading the pack for eccentricity, however, are the two unnamed assassins hired to dispose of the gang that kidnapped Minami. One is a bald man with a menacing glare (Yamamoto Shōhei) who travels with a pet parrot that sometimes sits on his arm or his shoulder, the other a ruthless crossdresser (played by real-life female impersonator Madame Joy), whose weapon of choice is a cut-throat razor and who that killing helps her to stay calm.

The story is initially a little convoluted, but its twists and turns are never confusing and allow all but the inattentive to quickly join the dots as it unfolds. Gosha certainly seems taken with the flamenco tunes, but outside of The Madrid, insanely prolific former Kurosawa regular Satō Masaru’s score has something of a late 60s/early 70s Lalo Schifrin vibe to it, something Gosha wisely drops when the fighting starts, which has the effect of accentuating the violence. The narrative flows smoothly and at an almost invisibly brisk pace, and has its share of stand-out scenes and set-pieces, some of which make inventive use of locations and help to broaden the look and feel what is primarily an interior-set film. These include a slickly handled ransom exchange on building site scaffolding, two scenes of violent combat in a coup full of doubtless alarmed chickens, and gangland murder in the corner of a junkyard that is packed with showroom mannequins, dead-eyed symbols of past executions that watch on accusingly as the latest victim is dispatched. It’s these offbeat elements and characters, together with the brutality of the violence, that help to lift Violent Streets above the already strong genre average. It may not quite hit the heights of the film that kick-started this second wave, but it’s is still a well-acted, neatly plotted and solidly directed work whose combat is bloody and unforgiving, and whose small but engaging eccentricities both reflect the influence of the late 60s work of Suzuki Seijun (Branded to Kill, Tōkyō Drifter), and point the way forward to the later yakuza films of Miike Takashi and Kitano Takeshi.

It's worth noting that the version on this Blu-ray has been subject to small cuts totalling 11 seconds by the BBFC, whose website to comply with UK laws on animal cruelty. The BBFC website provides the following details:

This work had compulsory cuts made to remove scenes of animal cruelty involving chickens. Cuts were made in accordance with BBFC Guidelines, policy and the application of the Cinematograph Films (Animals) Act 1937 under the Video Recordings Act 1984.

Further details of the cuts made van be found here:

https://www.movie-censorship.com/report.php?ID=204054

Sourced from a new restoration by the Toei Company, the 1080p transfer of Eureka’s Blu-ray (a worldwide debut on this format, no less) is framed in the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.40:1 and is in impressive shape. The image is clean and sits solidly in frame, and while a small number of shots are a tad soft (a grabbed wide shot of a colourfully disguised kidnap gang member merging with the daily commute, for example), I’m guessing this is down to the source material, as for the most part the image is sharp and the detail is clearly rendered. The contrast is pleasingly balanced, and while there’s and earthy look to many of the interiors, once out in the daylight, the colour feels as close to natural as the Fuji film stock would likely allow.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has a narrow tonal range, at least when it comes to the dialogue and Satō Masaru’s score, which has a treble bias and an occasionally crispy feel, though clarity is never an issue here, and there are no obvious traces of damage or wear. For reasons that may just be down to my ears or the pitch of the music, the flamenco numbers feel sonically superior. It’s probably just me – they are good, though.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default but can be disabled if you prefer. No dedicated SDH subtitles are included.

Tony Rayns on ‘Violent Streets’ (37:10)

Seriously, so well-versed is the venerable Tony Rayns in all aspects of Japanese cinema that I have a feeling you could pick any Japanese film or filmmaker at random, no matter how obscure, and he could talk about it in detail for a couple of hours straight. As expected, he is a fountain of information here, discussing not just Violent Streets but the evolution of yakuza film, director Gosha Hideo, actors Andō Noboru, Kobayashi Akira and Sugawara Bunta, the location work, and more. He clearly doesn’t rate this film as a top tier genre work, but does conclude by admitting that all these years after it was made it stands up rather well, describing it as, “an entirely serviceable and entertaining yakuza thriller.” Pleasingly, Rayns always uses the Japanese convention of family name first when discussing actors and filmmakers, one I also respectfully observe and have used throughout this review, in case you were wondering.

Fighting in the Streets (13:07)

Author, critic and Midnight Eye website co-founder Jasper Sharp is one of the few writers who could give Tony Rayns a run for his money when it comes to Japanese cinema. Here he provides the script and the narration for a visual essay that examines director Gosha Hideo’s earlier career, then focussing on Violent Streets, which he neatly describes as “a pretty eccentric entry into a genre hardly known for its restraint.” Although there is some minor information overlap with the Tony Rayns interview, this is also an essential watch.

Trailer (2:58)

The original Japanese trailer (with optional English subtitles that activate by default) unsurprisingly sells the film as a hard-boiled and action-driven gangster thriller.

Booklet

If two experts on Japanese cinema weren’t enough for you, a third arrives in the accompanying booklet in the shape of Tom Mes, author of numerous books on the subject and a co-founder of the aforementioned Midnight Eye website. Here, he takes a thoughtful and detailed look at both the film and its director, examining Gosha’s career both before and after the making of Violent Streets. Main credits for the film are also included, as is the usual viewing advice, and the booklet is illustrated with publicity imagery for the film.

Site regulars will be aware of my fondness for Japan and Japanese cinema, and this definitely includes the yakuza thrillers of the 1960s and 70s – several years ago I even sat in an independent cinema in Tōkyō and watched Fukasaku Kinji’s 1966 Rampaging Dragon of the North [Hokkai no Abare-Ryu] without English subtitles, and still enjoyed the hell out of it for its tone, its location work, and its tough action (that the print was in pristine condition also impressed). Violent Streets was new to me, and while my fondness for these movies inevitably meant I would be sympathetic to it from the off, Gosha’s handling, the ruthless and unglamourised nature of its violence, and a sprinkling of distinctively offbeat elements really give it an edge and make it a must-see for fans of the yakuza subgenre. It certainly looks damned fine on Eureka’s Blu-ray, and the special features are impeccably chosen. Warmly recommended.

|