|

It’s fair to say that Richard Woolley (born 1948) is an undersung filmmaker. He was active as a writer/director in the 1970s and 1980s, but since then has concentrated on educational activities, making music and writing scripts and novels. This box set, originally released by the BFI in 2011 and now reissued with additional extras (for details, see below) does not contain his earlliest work, such as the documentary We Who Have Friends (on attitudes to homosexuality in the wake of the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act), made while studying at the University of London, nor his short films made while at the Royal Academy of Art. It does however, contain everything since: two shorts made while in Berlin, two mid-length films and three full-length features.

Woolley’s roots were in experimental film, which bypassed commercial distribution and were shown largely as art gallery installations or in co-operatives, often made on formalist or structuralist principles. There’s an interest in the interplay of sound and image, often separated from each other in ways that you’d be unlikely to see and hear in a more conventional film. Yet, from Illusive Crime onwards. Woolley’s films do have narratives, however indirectly and obliquely they may be presented, and that’s more and more the case with his later films. The films also reflect Woolley’s experience of left-wing politics, including gender politics, and living in communes (in both England and Germany) which sometimes conflicted with his upper-middle-class background and upbringing.

Illusive Crime

Woolley received a bursary which took him to Berlin (the Western part of that then-divided city) and while there made two short films, included as extras in this set. He then returned to England.

Illusive Crime is a mid-length film which by many definitions wouldn’t qualify as a feature. It just about does by the IMDB’s definition of forty-five minutes and upward. In plot terms it’s a thriller set in a well-heeled middle-class setting, but Woolley’s treatment, based on the structuralist concerns of his earlier work, takes it somewhere else. First is what is effectively a prologue, a close-up of a sheet of paper as a typewriter produces a report. (As the film has no actual title card, you could suggest that the film is actually called the last words on the report, which are The Elusive Crime.) Then we move to the film proper, which is constructed around a series of recurring shots, from several points both outside and inside the house of a married couple (James Woolley and Amanda Reis), he with a job and given to discussing stock options with a colleague over a pint in the pub, she a housewife. Given that the positioning of the shots is the film’s guiding principle, we are not always in the best place to see what is happening, and we have to piece things together from the soundtrack, often coming from people partly or completely offscreen, and sometimes via a narrator. Very rarely do we see people’s faces clearly on screen. The story involves a home invasion and an act of sexual violence, and at a key moment Woolley breaks his pattern with a startling shot of female rear nudity. Nor is there much resolution to the “plot”. This caused some controversy, with some feminists condemning the film and others defending it.

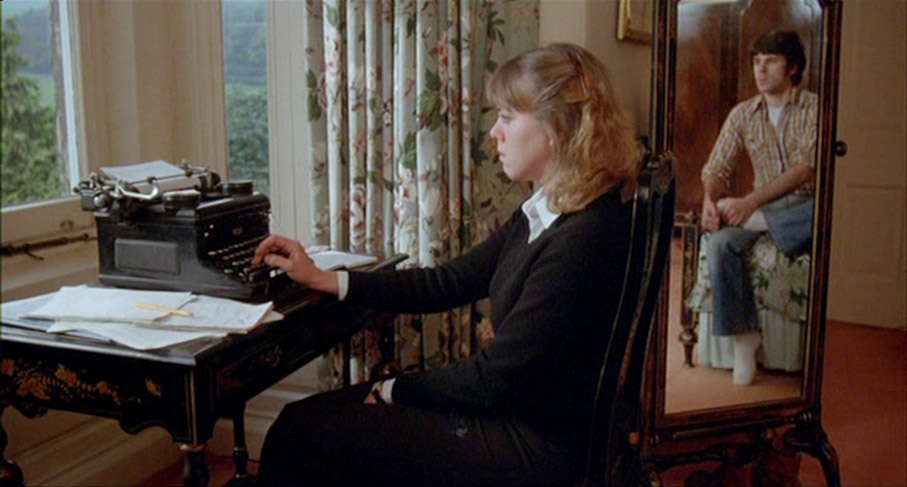

Woolley’s first feature film, like Illusive Crime shot and shown in 16mm, moves further away from the structuralist techniques, incorporating them in a more conventional narrative. That’s only relative at this stage. Telling Tales is still a challenging work, full of Brechtian alienation effects. While we are told a story, we are always aware that this is a film, a constructed work.

The Willoughbys (Patricia Donovan and James Woolley, the latter spelled this time as “Woolly” in the credits) are a middle-class couple with a son at boarding school and a maid, Sheila Jones (Bridget Ashburn), who is married to Bill (Stephen Trafford). The Willoughbys are discussing divorce, in part because she finds their life provincial and boring. Bill is a shop steward about to go on strike, industrial action which will affect Mr Willoughby.

It’s clear from the outset that we’re in the hands of the director of Illusive Crime. The opening shot lasts five minutes, with the first three having the camera fixed in a hallway, the doorway to the Willoughbys’ dining room making a frame within the frame. We listen to the dialogue between Mrs Willoughby and Sheila, the latter moving into and out of the frame. Then, the camera pans right to take in another doorway as the Willoughbys go into the dining room for their dinner.

Telling Tales is for the most part cinematically quite austere, shot in black and white. But at two points, we are told tales within the tale, as Mrs Willoughby talks direct to camera, and for the tale she tells, we are now in colour. Woolley shoots these sequences to make them look like commercials, down to Abba on the soundtrack. Though any kitsch is short-lived, as the second tale, about another couple known to the Willoughbys (and also played by Donovan and Woolley) stops any sentimentality in its tracks. (Maybe it’s a sign of the times, or an indication of the film’s feminist angles, but we have a doctor discussing a woman’s serious illness not with her but with her husband.)

Brothers and Sisters was Woolley’s first and only 35mm feature, made for the BFI Production Board (with Keith Griffiths on board as a producer) and given a cinema release in 1980. It also has, in David Barrett (Sam Dale) something of an autobiographical stand-in for the director and co-writer: a man from an upper-middle-class background, with a brother, James (Robert East), in the army, who is living with two women and one other man in a communal house run on impeccably left-wing (or, if unsympathetic, very right-on) principles. There is a serial killer, his victims all women and mainly prostitutes, operating, and that was autobiographical too. Woolley was living in the Chapeltown area of Leeds when Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, was committing his murders, and he, like every man in the area, was a potential suspect. This aspect of the film caused some controversy, though it’s clear that the film isn’t a dramatisation of the Ripper case.

Woolley tells his story in a complex manner, cutting back and forth between several timelines, so attention does need to be paid. The film is less about a resolution of a mystery (which we don’t have) and more about the attitudes, particularly to women in general and sex workers in particular, that feed into the killer’s actions. Carolyn Pickles plays two roles – Jennifer Collins, whose last hours we see during the film, and her sister Theresa Bennett, who works as a maid at the Barratt’s family home, and with whom Sam has had an affair. Pickles gives a superb performance, while Dale and East are also excellent. While James’s attitudes and politics are clearly further to the right than Sam’s, both are finely drawn. Telling Tales is a complex, often ambiguous film, and Woolley’s best.

The film was successful enough on its British release and at festivals overseas, though Woolley noted that it was beginning to find its audience when it was taken off many screens in favour of the next big Hollywood release (Coal Miner’s Daughter, as it happens). Attempts to set up another film with the BFI were not successful. He was asked to make things with a more working-class setting, which Woolley said he couldn’t do because that wasn’t his background. One project which didn’t get made was a comedy about the miners’ strike, which I suspect would have been nothing like the Comic Presents’ The Strike. Changes of decision-makers at the BFI meant that anything developed by the previous regime would no longer go ahead. However, Channel 4 began in 1982 and in its early days had its Eleventh Hour slot (11pm on Mondays) to showcase the experimental and challenging work that Woolley and others had made. Waiting for Alan, another mid-length film (not quite a feature) was made for and shown more than once on the channel – see discussion of the extras below.

Girl from the South was Woolley’s final feature film, and his most conventional. Young teenager Anne (Michelle Mulvany) travels from her well-off family in the South of England to stay with her grandparents (Daphne Oxenford, Alan Thompson). From the outset, Woolley counterpoints fiction with a harder reality: Anne is a Mills & Boon reader and her head is filled with romantic notions. (In a pointed scene, Woolley contrasts her reading her novel on the train with the man in the scene opposite, who is looking at Page Three of The Sun.) Anne meets the elderly and housebound Granny White (Rosamund Greenwood, in one of her last roles) and her grandson Ralph (Mark Crowshaw). Anne is attracted to Ralph, but her urge to help out is undercut by her naïveté, with disastrous results. Given the age of the protagonists, we’re in young-adult territory (not a complaint) and this is certainly more family- and audience-friendly than much of Woolley’s previous work, its themes of race and class lightly conveyed.

An Unflinching Eye is a set of four PAL-format DVDs (not Blu-rays), encoded for all regions. As mentioned above, the set was previously released by the BFI in 2011, but this new version adds hard-of-hearing subtitles to the four features, two commentaries which had been recorded in 2011 but not used, and a booklet. The set carries a 15 certificate, due to Illusive Crime and Brothers and Sisters (which had a AA certificate in cinemas). Girl from the South is a 12, and Telling Tales, which was an A in cinemas, a PG. The short films don’t appear on the BBFC website at the time of writing, though Kniephofstrasse is by some definitions a documentary so presumably exempt from classification – there’s nothing in it beyond a U certificate anyway.

Girl from the South

The running times given in this review are those on these discs, which are PAL format and playing at twenty-five frames per second. As most, if not all, of the films were shot and shown at twenty-four fps, PAL speed-up has come into play. (There’s a giveaway in Telling Tales, with shots of television screens, broadcasting at the PAL frame-rate of twenty-five fps (fifty fields a second) but captured at twenty-four by the film camera, with a black bar scrolling up the screen.)

With one exception, all the films were shot in 16mm and are presented in a ratio of 1.33:1. Brothers and Sisters, originated on 35mm, is in 1.85:1, widescreen-enhanced on this DVD. The 16mm-originated films are inevitably softer and grainier, but given that we are watching in standard definition, all quite pleasing.

The soundtracks are all mono, as they would have been in showings in cinemas and elsewhere. There are no issues with them, as all are clear and well balanced. English subtitles are provided for the hard-of-hearing on the four features, while the two German-language shorts have fixed English subtitles. So that leaves just Waiting for Alan putting the hard-of-hearing and non-speakers of English as a first language at a disadvantage. There are some typos (at least on the checkdiscs viewed, which may not reflect the final versions) but the subtitles are otherwise accurate.

Commentaries by Richard Woolley

Woolley provides commentaries for Telling Tales and Brothers and Sisters. These were recorded in 2011 but not used on the previous DVD release. While not without humour, these tracks have their dry moments as Woolley discusses his aesthetic strategies, which sometimes leaves him describing what we can see on screen. That said, there are quite a few anecdotes to be had, especially in Brothers and Sisters with its autobiographical resonance. For example, a man with prominent sideburns making a few brief, and uncredited, appearances in that film is Brian Hibbard, an actor and singer, best known as the original lead vocalist of the a capella group The Flying Pickets.

Interview with Richard Woolley (23:06, 14:12, 25:59, 16:12)

This is split into four parts, one per disc. Woolley is interviewed, in 2011, by Professor Andrew Tudor (who remains offscreen) and talks about his life and career up to the end of the period covered by the box set. Woolley is an engaging speaker, not afraid to name some names (including the structuralist filmmaker he seems to find cynical, prone to splicing together clear and black leader film in various combinations and calling it an art installation). Another story of his life in Berlin is his meeting with Rainer Werner Fassbinder, whose early films used similar techniques. Fassbinder invited him to a gay club, which Woolley declined.

Kniephofstrasse (24:21)

Drinnen und draussen (Inside and Outside) (33:37)

These two “films von Richard Woolley”, both made in 1974 and shot in 16mm black and white, take Woolley’s formalist interests further than anything else in the set. Kniephofstrasse (filmographers and pedants should note that the title on screen is actually Kniephofstr) is entirely non-narrative. It’s a series of shots, mostly overhead from the window of the room where Woolley was living, at different times of day of night, speeding up and slowing down, the film divided into twenty segments of equal length. In Drinnen und draussen, a young man and woman (Wolfgang M. Mueller and Ulrike Pohl) sit in the front room of a commune, with a large window looking out on the street, while a pianist plays on the soundtrack. This is intended to illustrate the two young people’s lives under two different social systems (those of West and East Germany) which force in their different ways conformity on their citizens. However, connection is possible, in the form of a kiss. Those well-versed in and sympathetic to experimental film movements of the time may get more out of these films than others, who will undoubtedly find them hard work.

Waiting for Alan (42:01)

Made for Channel 4 in 1984 and shown more than once by them (its short running time fitting into an hour-long slot with the commercials), Waiting for Alan puts its feminist concerns front and centre. There’s a possible nod to Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman (though Woolley’s film is a fifth of that film’s length) in its depiction of the domestic rituals of housewife Marcia (Carolyn Pickles), husband of the eponymous Alan (Anthony Schaeffer), trying and failing to communicate with him. She may live in a big house, with a gardener and a maid, but she is bored out of her mind. Suddenly, a short way in to the film, she breaks the fourth wall as Woolley’s protagonists have done before (in Telling Tales especially) and addresses us directly, but it may have something to do with her ability to find her voice or to have one in the first place that she is constantly interrupted by in-scene dialogue. Her situation is paralleled by that of her maid, Mrs Betts (Joyce Kennedy), whose husband is out of work and has no job to come home from, but still expects his tea. Both women resolve their situations in the same way, Woolley linking them to each other in the final shot, more of a firm resolution than in Woolley’s other films.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available in the first pressing only, runs to thirty-six pages. It begins with an essay by Anthony Nield (no spoiler warning, and these are films hard to spoil in the conventional sense, but please note that there are spoilers). This covers Woolley’s life and career up to the point where the films in this set leave off, and makes a case for Woolley being a filmmaker worth paying more attention to.

This is followed by “Writer as Director: A Case Study – Brothers and Sisters, 1980” by Woolley. This begins with a quote from Sergei Eisenstein’s The Film Sense which leads in to a blast at the formalaic nature of most film scripts, especially those aiming for financing by commercial companies, to the point where anything which doesn’t adhere to a standard three-act structure is rejected out of hand. However, he does find inspiration in some filmmakers out there, particularly Michael Haneke. He goes on to describe his methods in writing Brothers and Sisters and constructing its several timelines, with extracts from the screenplay as originally laid out. He also describes how some shots – a six-minute long take, for example, worked in the screenplay but didn’t in the film as it was edited.

Also in the booklet are full film credits, credits and notes for the extras, and stills.

Richard Woolley is no longer active as a director, but the films he made in the 1970s and 1980s make up a small but distinctive filmography. This DVD box set is a welcome chance to discover his work.

|