|

If you're an animal lover – and I'm talking about all animals, not just the cute, fluffy variety – then you might want to shield your eyes for the first minute of A Time for Dying. It opens like a wildlife documentary, with a rattlesnake coiling up for a doubtless lethal a strike on a baby rabbit, an assault that is violently cut short when a bullet blows the head of the snake clean off. And yes, like those unfortunate chickens at the start of Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it's done for real. It transpires that the shot was fired by Cass Banning (Richard Lapp), a baby-faced young sharpshooter fresh from the farm who is heading to the optimistically named Silver City to put his father-taught skills to some use, but who cannot bear the thought of a nasty rattlesnake killing a poor innocent bunny. It will be a while before the full weight of the symbolism of this opening sequence really hits home.

A few seconds later Cass encounters three riders, who from their triangular formation alone look set to give him trouble. They're led by Billy Pimple (nicely played by Bob Random), a young and intimidating gunslinger who appears to have been nicknamed for his still visible acne and who wants to know who was shooting at whom. When the nervous Cass explains about the rattlesnake and the rabbit, the irate Billy comes to the defence of the snake, adding another layer to the animal metaphor. For a short while, it looks as if Cass is going to have to put his pistol skills to the test, but when he attempts to diffuse the situation by cheerfully asking Billy what's happening in Silver City, Billy unexpectedly loosens up to tell him about a new girl who is on her way to town. The big joke is apparently that she doesn't realise that Mamie's – the establishment that she landed a job at – is the town's combination saloon and brothel. This notion has Billy giggling helplessly in a way that I, for one, did not find comforting. He also warns Cass that the citizens of Silver City don't take kindly to strangers walking around with their guns tied down as his are,* and advises him that Silver City is no place for a kid. When Cass foolishly responds, "Well, you were just there," Billy loses his rag, and barks furiously, "I was just passin' through, and I ain't no kid!" Fortunately for Cass, Billy and his boys then elect to ride on, leaving the visibly shaken Cass to continue his journey.

On arriving in Silver City, Cass has two things quickly confirmed. Firstly, that what he said about local opposition to strangers bearing sidearms was true, and secondly, that Billy is the volatile outlaw that those worrying first impressions suggested that he was. He's also someone who so hates seeing his face on wanted posters that on his last visit to Silver City he emptied his gun into one that was pinned to the wall of the saloon. In a sudden and rather rash display of his talent, Cass responds to this news by shooting another poster off the wall with a speed and pinpoint accuracy that dazzles Sam and the two ageing barflies who goaded him into it. "This here boy is even better and even faster than Billy!" Sam exclaims when the good women from Mamie's appear to enquire about the commotion. Later, we'll be given cause to recall that observation.

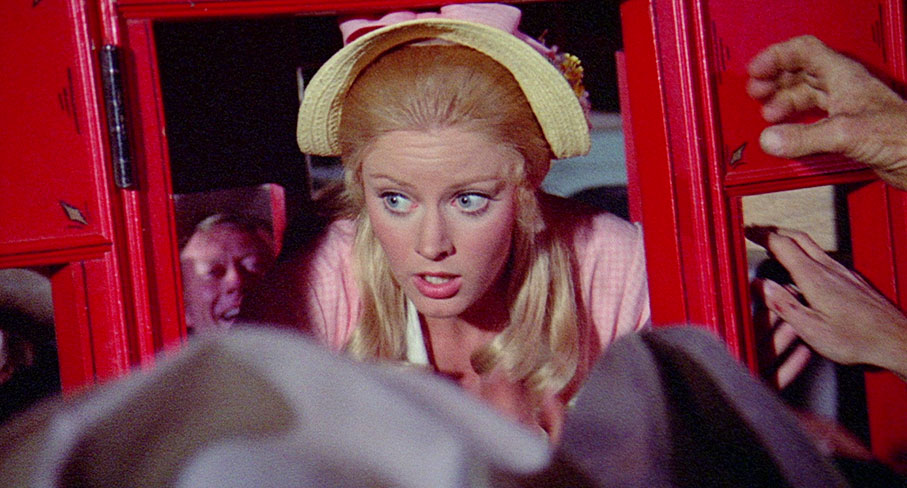

A short while later the stagecoach rolls into town, and the menfolk – whose wives, if they have them, are nowhere to be seen – all swarm around it like a swarm of hungry and noisy hornets, trapping new arrival Nellie Winters (Anne Randall) in the coach. Suddenly overwhelmed with concern for her safety, and just a little smitten by her beauty, Cass announces that he is going to rescue her, heroic intentions that get off to a shaky start when the saddle on his horse spins round onto the animal's belly, forcing him to ride bareback instead. But rescue Nellie he does, and the two ride off into the night and away from doubtless crestfallen crowd. They don't know where they're going, but Cass reasons the road that brought the stagecoach in must lead somewhere. Yeah, sounds like a plan.

Now for this viewer at least, A Time for Dying has so far felt a little off-kilter, and I'm not sure I can easily pin down why. Cass is certainly a bit of an oddity, his almost cherubic features and childlike concern for a baby rabbit's welfare being somewhat at odds with his finely honed pistol skills and gunslinger ambitions. Upbeat and impetuous, he's also visibly intimidated by Billy and his older companions, swallowing and sweating nervously both during and immediately after their encounter. When he pulls Nellie onto his horse and gallops out of town, he's given no thought at all to what he should do next, putting his faith instead in the notion that shelter will be walking distance away on a road that theoretically could go on for miles. And Silver City is not without its oddities. Before responding to Cass's enquiries, bartender Sam insists on downing a pint of beer with two raw eggs floating in it for breakfast, something actor Ron Masak clearly does for real. There's a nagging sense that on discovering that this was either Masak's party trick or part of some strange health regime, writer-director Budd Boetticher – yep, that Budd Boetticher, more on whom shortly – just couldn't resist putting it in the movie.

Then, just as we're wondering what fate has in store for Cass and Nellie, a new and tonally different chapter begins, one set in the small town of Vinegaroon and in which the two are temporarily relegated to supporting characters. Taking centre stage here is the true-life character of Judge Roy Bean, who as played by Victor Jory is a grizzled alcoholic who holds court in clothing he's probably worn for several months, stores his false teeth in a cup of whiskey, and who has a bar installed in the courthouse so that everyone can have a drink between pronouncements, himself included. He dispenses justice with a mix of poetry and cold-hearted ruthlessness, as his first, innocent-looking young customer (played by Audie Murphy's son, Terry) discovers when Bean waxes lyrical about the magic of the changing seasons, then slams his hand down on his desk and furiously barks, "But you won't be here to see none of it!" and orders the startled lad's immediate execution. Cass and Nellie's story collides with this one when they are hauled before Bean for sharing a hotel room without being married, an interesting bit of moralising for a town that is a short ride away from the region's busiest brothel. The judge solves this affront to Christian moral values by marrying Cass and Nellie on the spot, and later takes a liking to Cass because he's heard of the actress Lily Langtree, whom the drunken and slovenly Bean has never met but claims nonetheless to be in love with.

Where the film goes from here is something best left for adventurous viewers to discover for themselves, although it is, as noted in the commentary track, a film constructed from loosely connected chapters rather than one with a smooth narrative flow. There's almost a sense that the script was assembled from a series of separately written scenes, and that ways to move from one of them to the next were concocted on the fly when the shoot began. Then again, it's always possible that the low budget and tight shooting schedule (principal photography was completed in just over two weeks) forced the dropping of whole sections of a longer screenplay. There's also a sense that some scenes are only there at all because Boetticher thought they might be fun to stage, such as the boisterous wedding celebration chaired by Bean, or when bandits kidnap Nellie and ride into Silver City with the presumed intention of getting drunk and sexually assaulting her, but end up letting her run free and just wildly shooting up the town instead

The story of how this film came to be is one you'll come across a few times in this disc's special features, and may well be relevant to the uneven nature of the result. In 1968, actor Audie Murphy's box office mojo had begun to seriously wane. A teetotalling, non-smoking WW2 hero (Murphy was famously one of the decorated American combat soldiers of the war), Murphy nonetheless had a weakness for gambling and had run up some sizeable debts with potentially dangerous people. He had remained friends with Budd Boetticher after starring in the his 1951 debut feature, The Cimarron Kid, the first of a run of genuinely great westerns made by the director in the 1950s. Having spent much of the past decade chasing his dream to make a documentary on his friend, bullfighter Carlos Arruza, Boetticher had now also fallen on creative hard times. He and Murphy thus teamed up to form Fipco (First International Planning Company) to make A Time for Dying, with Boetticher directing and Murphy acting as producer, but also making a brief appearance in the film as Jesse James. As a performance, it could well be Murphy's finest, an engagingly low-key portrayal that makes the best of some of one of the script's more eloquent lines. But there's no doubt that it also sugar-coats a notoriously psychopathic outlaw in a manner that harks back to the romanticised film portrayals of James and his gang of past years. Which is all well and fine, but A Time for Dying was made when the genre was undergoing revisionist change, and was first shown just three months after Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch hit cinemas and transformed the genre forever.

A Time for Dying proved to be a fateful film for both Murphy and Boetticher, with the title in particular having a retrospectively ominous ring. Although his Carlos Arruza documentary Arruza was released in Mexico in 1971 and North America in 1972, Boetticher never directed another dramatic feature. He did write a script for Two Mules for Sister Sarah (1970), but made no secret of his deep unhappiness at the changes made to the characters and story by screenwriter Albert Maltz and director Don Siegel. Further collaborations planned with Murphy were planned, but in May of 1971, Murphy was killed when a private plane in which he was travelling crashed into Brush Mountain in Virginia. The film was also no career launcher for young actor Richard Lapp, whose body of work – just four credited film roles, two uncredited bit parts, and a few guest appearances in TV series – I was previously unaware of. Anne Randall also never made it as a female lead, but was at least kept busy in the 1970s in a range of film and TV supporting roles, and did play the title character in the 1973 exploitation movie Stacey, directed by Andy Sidaris.

A Time for Dying is a bit of an odd fish. As I noted above, it plays at times like a series of loosely connected, sometimes differently toned standalone scenes, and despite an unusually brief running time of just 72 minutes, is built around an essentially simple story that could have been told in half of that time. Richard Lapp, whom rumour has it was cast because he resembled a young Audie Murphy, certainly has the look of an innocent farm boy taking his first over-confident steps into the wilder world. Those hesitant facial close-ups during his early encounter with Billy Pimple show that he knows how to act for the probing eye of camera when required, but whether he has what it takes to carry the movie is open to question. The film itself has prompted some hostile (and occasionally facile) comments from IMDb users, and I'm certainly not going to claim it's up there with the movies that made Boetticher such a giant of the genre. Indeed, for much of my first viewing I found myself struggling to engage with its uneven structure and uninvolving lead characters, right up until…

That first time around, everything changed for me when the film moved into its climactic scene. In the spirit of avoiding major spoilers, I won't get into the details of what unfolds, but on my first viewing, this is where those sometimes disparate elements really coalesced in a rivetingly staged main street confrontation that breaks with genre tradition by playing out in the blackest of nights. It's here that Boetticher's skill as a filmmaker and western storyteller really kicks into high gear, and where cinematographer Lucien Ballard (who also shot the aforementioned The Wild Bunch) makes the lighting and framing as much a part of the storytelling as the action and dialogue. It's a beautifully handled sequence whose pivotal moment prompted me to let out a yelp of shocked surprise, and to start re-evaluating the purpose and thrust of all that had gone before. There's also a final coda that suggests one aspect of the story is set to repeat itself ad infinitum, one that seems keenly aware of where American filmmaking would be heading in the decade ahead.

Armed with the knowledge of how the story ultimately plays out, together with a clearer understanding of the film's underlying themes, a second viewing proved considerably more rewarding than the first. Yes, those chaptered tonal shifts still jar a little, and I still found myself observing Cass with a sympathetic eye instead of fully engaging with him as a character, but the film's narrative compression made a lot more sense, and seemingly superficial or throwaway elements could now be seen as visibly laying groundwork for the film's striking finale. I couldn't shift the feeling that A Time for Dying is times like a series of sketches for an ambitious painting that required more time and money to complete, but as one of cluster of films from the period that were caught midway between the genre traditions of the past and the unfolding revisionist works of the decade to come, it's an uneven but oddly fascinating work.

The result of a new restoration from a 2K scan of the original negative by Powerhouse Films, the 1080p transfer of A Time for Dying is presented on this Blu-ray in two aspect ratios, a 1.37:1 open matte version that includes the whole image as recorded by the camera, and the 1.85:1 theatrical version, which is framed how the film would have been seen in cinemas. I initially opted for the widescreen version for the more authentic cinema experience (well, as near as you can get to authentic in a darkened living room), and the framing never felt overly cramped. Yet I'd also argue that the open matte version never feels 'loose' by comparison – even when there is space above the heads of the characters, there's never a sense that it needs tightening up. The colour palette has that very slightly pastel leaning hue that was common to 35mm film stock of the day (the stock used here was by DeLuxe, in case you're interested), but in other respects the colour is handsomely captured, with vibrant blue skies and a strong reproduction of brighter coloured clothing and set dressing. The contrast is very nicely pitched, and with walloping black levels when the lighting demands, which proves particularly important in the night-set climax.

Picture detail is usually crisp on close-ups, though can soften a tad on wider shots, but herein lies an interesting difference between the widescreen and the open matte versions. The widescreen theatrical version was created by masking off the top and bottom of the 1.37:1 image recorded by the camera, resulting in a 1.85:1 image that almost fills a 1.76:1 TV screen. The 1.37:1 version is presented in the usual manner for this format, with black bars on each side of the image. Thus, the 1.85:1 version, as it appears on a widescreen TV, is effectively an enlargement of the 1.37:1 framed 2K scan of camera negative, which is why that 1.37:1 open matte presentation not only seems a little sharper than its widescreen brother, but the film grain is noticeably less prominent. Both transfers are impressive, but while the framing on the widescreen version feels 'right' for the film, visually the image on the 1.37:1 open matte version definitely has the edge.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track may have some expected restrictions in the dynamic range, but is otherwise solid, with clear presentation of the dialogue and Harry Betts' unmistakably 1960s-leaning score, and robust reproduction of gunshots and other louder sound effects.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with C. Courtney Joiner and Henry Parke

Screenwriter and novelist C. Courtney Joyner and screenwriter and True West magazine editor Henry Parke here provide a nicely balanced and thoughtful analysis of an unusual western. They outline the background to the film's production, provide details on the actors, praise Lucien Ballard's cinematography, and note the echoes of Sam Peckinpah's 1962 Ride the High Country, which was also photographed by Ballard. Having interviewed the film's female lead, Anne Randall, Parke is able to share her memories of the shoot, the most amusing of which is her claim that her young co-star was cast because of his looks, and that she wouldn't have had him as a husband because he was a dork. The claim once made by Boetticher that the film was never meant to be released caught me by surprise but perhaps explains its uneven tone, and both men lay into the film's mythologising of Jesse James, claiming that Murphy's portrayal is as far from the real James as you're likely to find. Joyner notes that the speech Murphy delivers as James is "interesting, but is also from outer space." Good stuff.

Christopher Petit: A Sense of Poetry (13:59)

Given that he's filmed in the same location as the interview conducted for the Indicator Blu-ray release of his 1982 An Unsuitable Job for a Woman, I'm guessing that writer and filmmaker Christopher Petit expressed an interest in this film and was asked if he would say a few words about it for this disc – he even begins by admitting, "I've been asked to talk about A Time for Dying…" Either way, it was a good call, as he has a thoughtful and sometimes unconventional take on the film, opening with the ominous proclamation, "Seen in any conventional sense, it's a very bad film," then going on to justify why it is nonetheless of considerable interest. He notes that the dialogue reminds him of a Bob Dylan song, compares the two old guys in the Silver City bar to Statler and Waldorf from The Muppet Show, and after praising Audie Murphy's performance, he rather wonderfully suggests he is like a ghost in his own film.

Kim Newman: The Men Who Shot Jesse James (20:04)

Here writer and novelist Kim Newman draws on his encyclopaedic knowledge of genre cinema to explore all of the portrayals of Jesse James in American westerns, from the 1921 silent Jesse James as the Outlaw (in which James was played by his real-life son, Jesse James Jr.) to Andrew Dominik's masterful The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007). He dispels the long disproved myths that James was a Robin Hood-like figure, a romanticised view of a ruthless outlaw that persisted for decades, and salutes Audie Murphy's performance in A Time for Dying as perhaps the finest of his career.

Booklet

Leading the way here is a terrific essay on the film by writer and producer Paul Duane, who so closely echoes my thoughts on some aspects I started to worry about accusations of plagiarising his text. He builds informatively on each of these areas, quoting relevant dialogue and source material to expand on information delivered in on-disc extras. This is followed by a 1969 Los Angeles Times article by Kevin Thomas that talks discusses was then Boetticher's latest project, and includes quotes about from the director an untainted-by-reality version of how the film came to be made. Next up is a 1969 overview of the career of war hero and actor Audie Murphy by Sandy Gardiner for the Ottowa Journal, which is followed by a revealing interview with Murphy conducted by Bill Libby and published in the San Antonio Express-News after the actor's death. Murphy is sometime brutally honest about his problems, his wartime experiences and even his abilities here – when asked about his rise to stardom in the 1950s, Murphy responds, "I had no talent. I told directors that. I didn't have to tell them. They protected me. I made the same movie twenty times. It was easy. But it wasn't any good. I never got to be any good." On the evidence of is small role in A Time to Dying, I beg to differ. This leads into a 1971 interview conducted with Budd Boetticher by Dorothy Manners for the Daily Advertiser a month after Audie Murphy's death, in which the director reflects on the making of A Time for Dying and his hopes for its belated release. Finally we have the booklet's oddest inclusion, a chart published in the French film journal Image et son that claims to plot the 'variations in dramatic emotion' over the course of the film's running time. I'm sure the original creator had his reasons.

A review that was delayed by my daytime workload bleeding into my free time that also stuttered along while I tried to make up my mind how I felt about a film that I quickly discovered needed that always recommended second viewing to really get a handle on. I don't think it's a great film, and the jury's out in some quarters over whether it's even a good one, but the dissatisfaction I felt for much of my first viewing dissipated when I gave it a second look, armed as I was with the knowledge of its narrative trajectory. It's an intriguing and frankly appropriate film to find on the Indicator label, and the special features, though limited in number, are all of a high quality and really contribute to your understanding and appreciation. Some will doubtless completely disagree, but I'm still going to have to recommend this disc, particularly to those with an interest in westerns that don't quite conform to expected genre norms.

|