| |

“A scientist in his laboratory is not a mere technician: he is also a child confronting natural phenomena that impress him as though they were fairy tales.” |

| |

Marie Curie |

| |

“There is nothing more dangerous in this world than an angry scientist.” |

| |

Abhijit Naskar, Vatican Virus: The Forbidden Fiction |

If Universal’s 1930s horror output was responsible for hooking me on cinema at a formative age, it was the horror-tinged science fiction films from the 1950s that really cemented my love for the medium. This time, however, the films that had me riveted to small monochrome TV screens as a child were not the product of a single studio. Warner made the desert a scary home for giant ants in Them! (1954), Twentieth Century Fox brought an alien ambassador to Earth with a dire warning in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1958), and Universal convinced us that everyone we knew could be replaced by shape-shifting aliens in It Came From Outer Space (1953), a soon popular notion that also gave us Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Allied Artists, 1956) and I Married a Monster From Outer Space (Paramount, 1958). As a kid, I absolutely adored these movies, despite the fact that they scared the bejesus out of me. When I revisited them years later with my cynical adult eyes, I was delighted to discover that they held up, and still had the power to give me nostalgic chills.

Although now one of many players, Universal did have a particularly good run here, one that included Creature From the Black Lagoon (1954) and its two sequels, Revenge of the Creature (1955) and The Creature Walks Among us (1956), as well as Tarantula (1955), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) and the above-mentioned It Came From Outer Space. Crucially, all but one of these titles was directed by Jack Arnold, a busy filmmaker whose enthusiasm for horror and science fiction made his contributions to this run of genre movies something rather special. In a career that includes over 80 titles in a wide variety of genres, these remain the films for which he is primarily remembered, the last of which has been included in this set.

I’ve covered the three films separately below, and should note that the coverage of The Monolith Monsters has been adapted from the review I wrote in 2014 of the now discontinued German Anolis Entertainment Blu-ray release of the film. It’s a movie I have something of a history with and a lingering affection for, but I also enjoyed the hell out of the other two films in this set, Man Made Monster and Monster on the Campus, both of which I caught here for the first time. I should note that that there are small sprinkling of spoilers in the coverage of those two films, so newcomers should tread carefully in the second half of each review.

Nobody did tormented angst quite like Lon Chaney Jr. Here he plays Dan McCormick, the only survivor of a spectacular accident in which a bus crashes into an electrical pylon that fries his fellow passengers, shown in an impressive (albeit borrowed) bit of model work. Indeed, when he’s visited in hospital by curious scientist Dr John Lawrence (William B. Davidson), he appears to be undamaged and in sparkling health. Maybe, just maybe, it’s down to his carnival act as Dan the Electric Man, in which he receives electric shocks for the amusement of paying customers. Dr Lawrence is certainly keen to find out more, and persuades Dan to drop in to see him when he is released and act as a subject for experiments on human electrical resistance. He’s assisted in this process by his junior colleague, Dr Paul Rigas (Lionel Atwill), who is conducting his own, more morally suspect research into the potentially manipulative power of electricity.

I’ll pause here to note that Man Made Monster was an early entry in what became known as the Mad Scientist cycle of the 40s and 50s, and in some ways sets a template for future works in this subgenre. The lead experimenter here may be one of the nicest people you could hope to meet, but his colleague fits the profile to a tee. Another common trait of such films was that scientists were often widowers with a single pretty daughter, granddaughter or niece of dating age with whom they shared a house. Somehow, these strikingly attractive young women were always unattached, and wouldn’t you know it, the man they have been waiting for turns up during the course of the unfolding story. Here, the female role is filled by Dr John’s niece June (Anna Nagel), who initially deflects the attentions of young reporter Mark Adams (Frank Albertson), but in the blink of a scene change is going out on dates with him like they’ve been together for months.

Rigas doesn’t really get the chance to play the scientific obsessive until Lawrence goes away for a few days to a conference, and when Dan shows up for his regular appointment, Rigas assures him that he’ll be continuing his colleague’s tests in his absence. Instead of the mild dose of electricity meted out by Lawrence, however, Rigas whacks the power up to a dangerous level, prompting Dan to lose consciousness and leaving him disorientated when he comes to. As these new treatments continue and the voltage is further increased, the impact on Dan’s personality is considerable, transforming this once jovial and energetic man into a morose and uncommunicative shell of his former self, but this is only the first stage of Rigas’s plan.

There’s more than a whiff of the original movie mad scientist, Victor Frankenstein, about the fanatically driven Rigas, something echoed in the briefly seen electrical equipment cutaways borrowed from the Universal Frankenstein films. Unlike the misguided Victor, however, the experiments that consume Rigas have deeply sinister overtones. “I believe that electricity is life,” he tells Lawrence at one point, “that men can be motivated and controlled by electrical impulse supplied by the radioactivities of the electron. That eventually a race of superior men could be developed, men whose only wants are electricity.” What was going on elsewhere in the world in 1941 when this film was made again? Ah, yes…

Rigas also seems oblivious to the negative effect these experiments are having on the unfortunate Dan, who is now in a glum state of utter dependency and only lives for the jolts of electrical power that Rigas continues to regularly deliver. Tucked beneath a science fiction allegory it may be, but this may well be the first time that Hollywood explored the misery and consequences of addiction – swap electricity for heroin and Dan’s journey could be the basis of a modern social realist drama. Indeed, at one point his condition and morose dependency on the treatments dished out by Rigas reminded me of scenes in French Connection II when a kidnapped Popeye Doyle is forcibly injected with heroin by his nemesis, Alain Charnier, and ends up just sitting on his bed waiting listlessly for his next hit.

Lionel Atwill is in full enjoyable flow as the increasing demented Rigas, never playing him as a pantomime villain and able to switch convincingly back to Nice Professor mode when the conciliatory police are just too charmed by him and his position to consider that he might have committed a serious crime. There’s a future for these guys in London’s Metropolitan Police. By portraying Dan in such an engagingly upbeat and energetic manner in the early scenes, Chaney makes that tortured anguish he was able to communicate with such aplomb really register here. Samuel S. Hinds, meanwhile, comes across as the epitome of gentlemanly decency as Dr Lawrence, which you know will bring him into conflict with morally bankrupt Rigas sooner or later. June Lawrence and Frank Albertson make for more likeable romantic leads than the genre norm as June Lawrence and Mark Adams, despite Adams’ wisecracking and overly pushy attempts to court June just minutes after first meeting her, a slice of gender politics that has aged like warm milk. Oddly enough, one of the touching performances comes from Corky the Dog at the Lawrence’s household pet, his friendship with Dan and seeming concern for his wellbeing laying the groundwork for a moment of genuine poignancy in the film’s final scene.

The ghost of Frankenstein (no franchise pun intended) does continue to hover over the film’s later stages, notably when the electrified Dan goes on the rampage, becomes hunted for committing crimes of violence, and at one point pick up and carries a swooned June in one of the genre’s most iconic poster images. There are, nonetheless, still several elements that set the film apart from its famous forebear. These include some smart optical effects by an uncredited John P. Fulton that make Dan’s hands and face glow with electrical charge, a willingness by Rigas to see Dan sent to the electric chair in order to trigger the next stage of the experimentation on him, and Dan escaping prison by threatening to unleash his stored-up electrical current onto the terrified warden walking slowly ahead of him. A nicely structured plot is nonetheless not without its holes, the largest of which occurs after Dan walks out of the prison with the warden as hostage, and the police somehow completely lose track of his whereabouts. Did it not occur to any of these dumbasses to just follow him from a distance? It’s night-time and he’s glowing! You could see him from a mile away! But it's a small gripe for a briskly paced, enjoyable performed, and highly entertaining slice of subtextually intriguing science fiction horror, one directed with style and assurance by George Waggner, who later the same year would again team up with Chaney for a nifty little film that you may just have heard of called The Wolf Man.

When I was a child, the scariest places on Earth were deserts of the American Southwest. I'd never been there, but childhood fascination with American 50s science fiction films had convinced me that just about anything could be lying in wait for those foolish enough to wander off the main road. Two films in particular haunted my formative years, Gordon Douglas's Them! and Jack Arnold's It Came From Outer Space. They left me in no doubt that the New Mexico deserts were home to monstrous ants, and that skulking away in the Arizona Badlands were slug-like, cycloptic blobs that could shape-shift into humans and replace my loved ones. I loved these movies to bits, and being scared by them remains one of the fondest memories I have of my childhood. It Came From Outer Space particularly obsessed me, and I remember doing endless drawings of its alien blob creatures when I was still a child. Later, I twice had the chance to see the film on the big screen in 3D (with cardboard glasses!) on a double bill with Arnold’s The Creature From the Black Lagoon, first at the beloved Scala cinema, and then at the Eros in Piccadilly Circus, the venue featured at the climax of An American Werewolf in London. By this point, I had become an enthusiastic fan of Arnold’s science fiction cinema and had seen most of the his key genre works of this period. He tended to direct from other people’s scripts, but did receive a story credit on two films. The first was for his own 1955 Tarantula, the second was on a far less widely seen work from 1957, the intriguingly titled The Monolith Monsters.

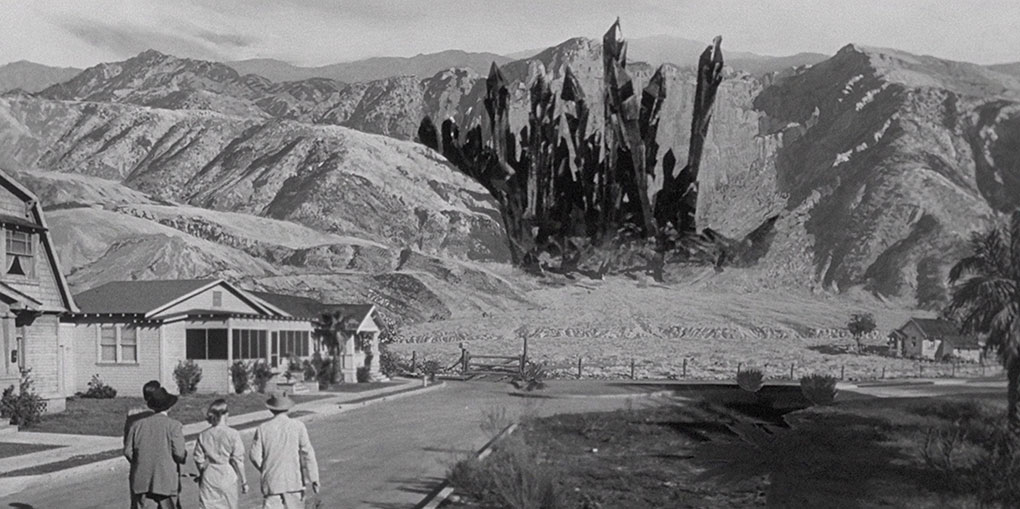

The setup is the standard 50s alien invasion tale with an intriguing twist. A meteor crashes in the desert outside of the small town of San Angelo in California, shattering into a multitude of small black crystalline fragments. The following morning, geologist Ben Gilbert (Phil Harvey) finds one of the rocks and takes it back to his office, where water spills on it and prompts it to expand. When the head of the San Angelo district geological office, Dave Miller (Grant Williams), drops round to see Ben the next day, he finds the office wrecked and Ben's body hardened as if turned to stone.

There were, effectively, two styles of science fiction film narratives at that time. There were those that kept you in the dark about what was happening until the truth was uncovered by the lead characters, and those that clued the audience in from an early stage, so that you might fret when anyone inadvertently made a move that might worsen the situation or place them in danger. The Monolith Monsters belongs firmly in the second category. We don't see exactly what happens to Ben, but we, and we only, have a clear idea what has caused it. We thus know before anyone in the film figures it out that these rocks are from outer space, that they're potentially deadly to humans, and that like Joe Dante's Gremlins, you must never get them wet. Thus, when Dave's schoolteacher girlfriend Cathy (Lola Albright) takes a group of kids on a field trip to the very same spot at which Ben found his sample, we're on edge even before young Ginny Simpson (Linda Scheley) picks up one of the rocks and takes it home to her parents' farmhouse. Her sensible mother (Claudia Bryar) refuses to let Ginny bring such a dirty object in the house, prompting a sigh of relief that is cut sharply short when Ginny takes her at her word and drops it in a bucket of water to clean it.

When fragments of the rock are discovered in Ben's office, Cathy recognises them as being similar to the one that Ginny picked up on the field trip. She, Dave and Police Chief Dan Corey (William Flaherty) thus head out to the Simpson farm, which by then has been transformed into an astonishing expressionist sculpture of twisted wood and black crystal. Seriously, this is a mother of a piece of set design, the work of art directors Alexander Golitzen and Robert E. Smith, and one that by rights belongs in a gallery on prominent display. But I digress. Ginny's parents are dead, but Ginny herself is still precariously in the land of the living, albeit in a comatose state. On the local doc's advice, Dave and Cathy drive her to the California Medical Research Institute in Los Angeles, where the professorial Dr Hendricks (Harry Jackson) discovers that whatever killed Ben is slowly transforming young Ginny into stone.

A few of the elements here were genre stalwarts even back in 1957, but are dealt with and moved on from at a disarmingly brisk pace. That the young and good-looking male and female leads are in love is no surprise (let's face it, if they weren't at the start then they would be by the end), but they're given precious little time to express it on screen. A warm greeting, a kiss and a reassuring word, and they're back into action, their encounters never slowing the flow of the narrative for more than a few seconds. And boy does the narrative move, breezing through a series of incidents, encounters and revelations with nary a pause, the savvy economy of John Sherwood's direction keeping everything clear without ever letting us feel we've fallen face-down into a bowl of exposition soup.

But it's when the rocks grow into huge monolithic crystals that the film really delivers on the promise of its title. Expanding skyward until toppled by the force of gravity, they crash down through farm holdings and shatter into thousands of smaller crystals that then also begin to grow, a cycle that looks set to repeat and expand until they reach the valley floor and lay waste to the town and everything beyond. It's a spectacularly realised vision, thanks to some excellent model work and over-cranking the camera by just the right amount required to convince us of the monoliths' gargantuan size and weight as they fall.

The thing that sets these particular aliens apart from the genre norm is that there is no conscious intent, malicious or otherwise, on the invaders' part. Their arrival on the planet was accidental, and their growth, multiplication, and effect on the human population is the result of a chemical reaction that is part of their organic makeup. In this respect, The Monolith Monsters is both a film of its time and one that looks unknowingly forward to the current pandemic, where humankind has come under siege from a primal organism that is just doing what it has to do in order to survive and propagate. At one point, the characters even speculate on how quickly and far the effect of the crystals will spread if unchecked, a favourite cornerstone of pandemic-related movies of recent years. Boy, have they found a grim new relevance.

I'm still not sure why The Monolith Monsters has not attracted the same sort of critical attention as some other notable American science fiction films of the 50s, or why it's been so hard to track down over the years, at least in the UK. Certainly, it lacks the subtextual politics that distinguish the best of these films, but its central conceit, its pacing, and its impressive production design and effects still put it on a par with its more widely seen contemporaries. The performances are all solid, but my favourite comes from an uncredited William Schallert as the wrapped-up-in-his-job weatherman that Dave calls for a rain forecast, a brief few moments of character humour in an otherwise straight-faced drama.

It's also worth noting that the ties with Jack Arnold go beyond his credit as the co-story writer. Director John Sherwood worked primarily as an assistant director and only helmed three features in the director’s chair, the second of which was The Creature Walks Among Us, the third film in the trilogy begun by Arnold's The Creature From the Black Lagoon and Revenge of the Creature. This film’s leading man, Grant Williams, went on to star in Arnold's most celebrated film, The Incredible Shrinking Man, and the opening meteor crash is an alternative take of the effects shot the opens Arnold's It Came From Outer Space. On a separate note, while it might be stretching it to suggest that The Simpsons creator Matt Groening is a fan of the film just because a family named Simpson figures in its story, it's hard not to break into a knowing smile when the professor who comes to Dave's aid turns out to be named Flanders. Intriguingly, that name appears again in...

To complete his collection of face casts tracing the evolution of humankind, Dunsfield University Science Professor Donald Blake (Arthur Franz) has just finished making one of his girlfriend, Joanna Moore (Madeline Howard), which will take its place at the end of the line as Modern Woman, next to the existing cast of Modern Man. Read what you like into the fact that no female equivalent is provided for the likes of Neanderthal Man or the long-since debunked Piltdown Man, and by positioning the new cast after Modern Man in his little exhibit, Donald seems to be suggesting that Modern Woman is an evolutionary step above her male equivalent. No arguments here.

It’s then that one of Donald’s students, Jimmy Flanders (Troy Donahue), arrives with the departmental van, in the back of which is a crate containing a large Coelacanth, a once thought extinct species of fish whose lineage dates back many millions of years. The creature has been shipped from Madagascar encased in ice that has since started to melt and is now leaking onto the road, where it is lapped up by Jimmy’s German Shepherd, Samson. This should set alarm bells ringing with anyone who knows their genre movies, particularly when Jimmy dissuades the dog with the line, “Come on, get away from that bloody water,” and he’s using the word ‘bloody’ here in its literal sense. When the normally friendly Samson then turns almost instantly feral, barking angrily at a terrified Joanna and attacking Jimmy, we have all the information we need to take an educated guess at what the origins of the monster of the title might prove to be. And when Donald then cuts his arm on the sharp teeth of the fish and accidentally dips the wound in the same water, the monster’s likely identity is all but confirmed.

A key appeal of Monster on the Campus, at least for this particular genre fan, is its refusal to go the way of the 50s teen horror works that its spell-it-out title seems to be suggesting it's part of. Despite what is clear from an early stage, the fact that Donald is being transformed into a murderous monster by this bacterial infection is not confirmed on screen until the final reel, and is instead repeatedly intimated by the circumstances surrounding attacks that are either not shown or only briefly glimpsed. That Donald is an easily likeable and clearly popular professor instead of an unsociable obsessive also lends the proceedings a degree of tragic pathos – in the opening scene he hugs Joanna and says to her warmly, “When I look at you, the future’s very bright,” a future that is soon in very considerable doubt.

Considering that we know what’s going on long before anyone in the film works it out, the interest lies less in the mystery of what is happening than how and when Donald’s terrible secret will be exposed, and what will likely happen to him as a result. His ultimate fate is dictated at an early stage by the fading but still lingering influence of the Production Code – if a character kills, then movie convention of the day means that he or she should suffer a similar fate. Clouding this a little is Donald’s unawareness of his actions whilst under the influence of the Coelacanth plasma (it’s best not to look too deeply into the science here), which acts a bit like the potion taken by a certain Dr Jekyll, transforming Donald into a murderous caveman but leaving him dazed and with no memory of what has occurred once he returns to normal. The circumstances of the first death put him in the frame with investigating police detectives, Lieutenant Mike Stevens (Judson Pratt) and Sergeant Powell (Phil Harvey), but the discovery of finger and handprints that clearly do not match his result in Powell instead being assigned to protect him against an unknown third party, one that Stevens deduces (logically, as it happens) may be specifically targeting him.

Monster on the Campus was the last of the science fiction/horror movies directed by Jack Arnold for Universal, and despite his claim that he only made it as a favour to first-time producer and former music supervisor Joseph Gershenson, he does an absolutely bang-up job. Individual sequences particularly impress, from the genuinely eerie discovery of the first body, found hanging bolt-upright by her hair with her eyes wide open, to a scene that shouldn’t by rights be as creepy as it is, when Jimmy, his girlfriend Sylvia (Nancy Walters), and Donald encounter a dragonfly that has been transformed by the plasma into a creature the size of a large bird. Arnold is aided here by ace cinematographer Russell Metty, whose impressive and extensive CV includes the likes of Touch of Evil, Spartacus and The War Lord, and whose use of smoothly executed dolly shots gives this low-budget genre work a sometimes A-movie sheen.

In common with the other two films in this set, the performances are robust across the board, in part because the actors take their roles as seriously as they would in a standard drama. Arthur Franz engages enough in a short space of time as Donald for us to feel for him when things take a dark turn, but ultimately it’s Madeline Howard’s engaging performance as Joanna that becomes the real for focus for audience sympathy. Judson Pratt proves pleasingly dependable and intelligent as Lieutanant Powell, nicely adding character to straightforward dialogue and peppering his performance with small but believable bits of business. Even Jimmy Flanders and Nancy Walters, the only two students on campus that we get to spend more than a couple of seconds with, are nicely underplayed by Troy Donahue and Nancy Walters. I also liked Helen Westcott’s too-brief portrayal of Nurse Molly Riordan, a woman with a serious crush on Donald, one the dozy git is just too devoted to Madeline to remotely reciprocate.

That the film consists mostly of build-up to a climactic transformation and countryside rampage is not an issue when the build-up in question plays out as arrestingly as it does here. Indeed, if there is a weak aspect, it’s that the monster promised by the advertising material is effectively just a man in a grotesque but ill-fitting mask who runs around grunting, seemingly only grabbing and carrying the swooning girl to provide a tried and tested image for the poster. For me, it’s here that the film loses its grip, being less focussed on character and story and all about a spectacle the budget or the tight shooting wasn’t really up to providing. The sequence still has its moments, notably the transformed Dan’s lingering memory of his affection for Joanna, and an unexpectedly brutal moment when he kills one of his pursuers by hurling an axe into the unfortunate man’s forehead.

Science fiction novelist turned screenwriter David Duncan keeps the dialogue efficient and largely believable, despite some best-not-investigated science, and an ‘oh come on!’ contrivance used to infect Dan with the plasma for a second time. He does play briefly with the idea that our genetic code dates back millions of years to primitive man, a concept that was at the core of Ken Russell's later science fiction masterpiece, Altered States. In a largely humour-free film, he does sneak in a single dryly amusing quip, when the University Dean Gilbert Howard (Alexander Lockwood) reveals that in the search of a possibly deformed sub-human, the detectives are fingerprinting the football squad. There’s also an in-joke that seems to have flown under the radar of most commentators and likely there purely for fans of genre cinema. It occurs when Donald makes an expensive phone call to Madagascar to enquire about the origins and transport of the Coelacanth fish, a call to an island that is home to strange creatures and where the principal contact’s name is Doctor Moreau…

The transfers for all three films appear to have been sourced from restorations carried out by Universal, and all are in seriously impressive shape, boasting a generous and attractive tonal range that nails the black levels and avoids any hint of highlight burn-outs, and displays a crisp rendition of well-defined detail. There are some faint traces of former wear that have been digitally cleaned up – something most visible in Man Made Monster, the oldest film in this set by several years – but for the most part the image on all three movies is clean of dirt and dust, with no movement in frame and a fine film grain. All three films look really good here.

Now let’s talk aspect ratios. All three films were shot in the Academy ratio of 1.37:1, but in the 1950s Universal’s preferred projection ratio for many of its films was 2:1 using a system that it labelled SuperScope. This was designed as Universal’s answer to CinemaScope, a then newly popular widescreen format developed by 20th Century Fox that worked by shooting with anamorphic lenses that squeezed a 2.35:1 image down to 1.37:1, which was then un-squeezed at the projection stage. SuperScope involved shooting in the regular 1.37:1 aspect ratio using normal lenses, then masking the top and bottom of the image at the projection stage to achieve the 2:1 aspect ratio. Because not all cinemas were capable of matting the film to the correct ratio, or perhaps of enlarging it to fill the screen once this was done, those making films using this process had to keep both aspect ratios in mind when framing shots.

Monster on the Campus open matte version (above) and the SuperScope version (below)

Usefully for comparison purposes, both the 1.37:1 and 2:1 versions of Monster on the Campus have been included in this set, and they help to illustrate the problems facing cinematographers when having to accommodate two ratios at the same time with the same camera. For the most part, the widescreen version feels comfortably framed, while the open matte 1.37:1 version feels a little loose, particularly when it comes to shots containing more than one character, which sometimes have a little too much dead space above the heads. But just occasionally, cinematographer Russell Metty and director Jack Arnold seem to completely disregard the effect that SuperScope matting will have on the 1.37:1 frame, resulting in a small number of shots that feel uncomfortably cramped when cropped down to 2:1. A prime example is the one pictured above, the midway point of a rather nice bit of character blocking that sees Lieutenant Stevens step out of two-shot and walk forward until his head fills the frame, an image that feels far better balanced in the 1.37:1 aspect ratio. It's also worth noting that the picture does seem slightly sharper in the open matte version, which is solely down to having more picture information in the same vertical space than the effectively zoomed-in SuperScope version.

The Monolith Monsters open matte version (above) and the SuperScope version (below)

Much of the above also goes for The Monolith Monsters, which was also shot in the Academy ratio with the intention of projecting at 2:1, and for the most part the characters are organised within frame with that in mind. That said, it seems likely that the special effects crew didn’t get the memo on this, as the hugely impressive wide shots of the towering crystals are sometimes clearly framed for the 1.37:1 ratio, as illustrated by the above effects shot comparison. I should point out that you’ll not be able to judge this for yourselves with this set, as only the 2:1 version has been included – the above grab is from a previous DVD release, where the film was framed 1.37:1. Interestingly, the restoration on this disc appears to be the same one used for the earlier German Anolis Entertainment release, and I’m thus guessing that the Universal restoration was only supplied to distributors in the SuperScope ratio.

Man Made Monster, having been made back in 1941, is in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1.

All three films have Linear PCM 2.0 dual mono soundtracks, and despite the expected restrictions in dynamic range, the clarity of the dialogue and effects, coupled with the fullness of the music scores, really lift these tracks above the genre average for this period, something particularly true of The Monolith Monsters and Man Made Monster. Seriously, I’ve heard soundtracks from late 60s films that don’t have the richness on display here.

Optional English subtitles are available for all three films.

Disc 1: MAN MADE MONSTER

Audio Commentary by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman

The first of two commentaries in this set by genre writers Kim Newman and Stephen Jones kicks off with a question about the missing hyphen in the title, before moving onto details about the film’s content and production. As ever, the two men are a bundle of knowledge and unbridled enthusiasm, and they cover a lot of ground in the film’s brief running time, including details on the actors (human and canine) and praise for the casting, the origins of the story and the development of the film, the glowing effect first used in the 1936 The Invisible Ray, the impact of the Hays Code on what could and couldn’t be shown, the music score, the climactic scene, and a lot more besides. They confirm that the original cut was longer and that it was trimmed down to facilitate more screenings per day of the double-bill that it was part of, and that it was originally planned as a project for Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Frankly, I’m happy with the cast we have.

There are two image galleries. Stills Gallery #1: Production Stills features 29 superb quality monochrome publicity stills, while Stills Gallery #2: Artwork and Ephemera has just 7 screens featuring posters, lobby cards, and a Universal Classic Collection video box

Disc 1: THE MONOLITH MONSTERS

Audio Commentary by Kevin Lyons & Jonathan Rigby

Genre writers Jonathan Rigby and Kevin Lyons get thoroughly stuck into a film they describe as being top of the second division, though do spend a little too much time picking holes in some aspects, much of which I found myself in complete disagreement with. Fortunately, compensation aplenty is provided by the wealth of background information on the actors, the filmmakers, and the science fiction boom of the period, as well as some interesting analysis of individual scenes and elements. We’re certainly on the same page when it comes to William Schallert’s uncredited performance as the weatherman, and there’s an entertaining moment when Rigby reads extracts from the film’s hyperbolic press book in the manner of an excited carnival barker.

Stills Gallery #1: Production Stills has 47 monochrome publicity stills, which include a few posed images and a couple of composites – the quality varies a little, but most are very good. Stills Gallery #2: Artwork and Ephemera consists of 7 screens of posters and lobby cards.

Trailer (2:05)

Not an easy concept to sell, I would imagine, and little about this trailer would prompt me to rush down to my local cinema to see a film I’ve now been a fan of for many years. It includes a little too much footage from the climax, but worry not, as the film apparently contains “The most startling science fiction concept ever brought to the screen!”

Disc 2: MONSTER ON THE CAMPUS

Audio Commentary by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman

Newman and Jones are back to examine a movie they intriguingly describe as, “an adult film for adults but aimed at a teenage market.” Areas covered here include producer Joseph Gershenson, director Jack Arnold, cinematographer Russell Metty, the impressive accuracy of the Coelacanth model, the actors and performances, the iffy make-up in the finale, and plenty more. They acknowledge the effectiveness of the film’s slow-build approach, question the paucity of students in a campus-based movie, and comment on the Jekyll and Hyde nature of Dan’s transformation, in the process suggesting that all film interpretations of that story are effectively tales of mind-expanding drugs. Far out.

This time, Stills Gallery #1: Production Stills has only 7 monochrome publicity stills, while Stills Gallery #2: Artwork and Ephemerais up slightly on its predecessors with 11 screens of posters, poster art, and a VHS cover.

Trailer (1:47)

“Your blood will chill in terror!” claims a trailer that reveals the ape man makeup from the final scenes, but since that’s all over the posters it hardly counts as a spoiler. Again, there’s a little too much of the climax, and the narrator has just a whiff of Criswell about him – Ed Wood fans will know who I’m talking about.

Booklet

Following the main credits for all three films, the meat of this 40-page booklet is an essay by film scholar, writer and researcher, Craig Ian Mann, and it’s an absolute belter of a read. Starting with the rise of the Universal horror film, Mann then gets into fascinating analytical detail on all three titles in this set, digging beneath the surface of the storylines to examine their socio-political subtexts. It makes for a consistently arresting read, albeit one that made my own scribblings feel woefully inadequate by comparison.

Another splendid multi-film Blu-ray release from Eureka, this one boasting three terrific horror-tinged science-fiction films from Universal’s second genre wave, all handsomely restored and accompanied by excellent commentary tracks, and an excellent booklet essay by Craig Ian Mann. I’m once again shoddily late with this review, due to more tiresome personal circumstances, but still wanted to give this release a serious push, in the hope that we will see more of its like in the future. Highly recommended.

|