|

When it comes to horror cinema, the writings of celebrated author Edgar Allan Poe have proved to be both hugely influential and, a tad paradoxically, notoriously difficult to faithfully adapt into films. Part of the problem lies in Poe’s preference for short stories over novels, tales that could be read in a single sitting rather than over the course of several days. While this may be fine for the reader, it presents a challenge for any screenwriter looking to fill a feature film running time with what may take less than 30 leisurely minutes to read. Even back in the early 1930s at the dawn of both the sound era and the American mainstream horror movie, when a feature film could run for just a whisper over an hour without complaints of being short-changed from the audience, there was just not enough of the right sort of plot or the expected range of characters in Poe’s more popular stories to satisfy the demands of a Hollywood commercial feature. This is probably why some of the more faithful adaptations of his work tend to be found in short films and in segments of portmanteau features, with feature adaptations tending to expand considerably on his words or use them as jumping-off points for their own stories, none of which is a problem if it’s done with the right degree of mystery and imagination.

The three features here, made by Universal between 1932 and 1935 as part of its classic horror cycle, are all nominally inspired by Poe stories, but while they’re happy to trade on the name recognition of the titles, only one of them even pays lip service to the text on which it is supposedly based. All three star Bela Lugosi and two of them also feature fellow horror icon Boris Karloff, who is always credited above his co-star and was paid considerably more, the reasons for which are speculated on by more than one person in the plentiful special features. The films in question are The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Raven (1935) and all three were made before the Production Code censoring of content in American movies really started to bite, and all include sequences and ideas that must have really wound up the self-styled moralists who wanted such films hidden from public gaze. All three are hugely enjoyable, and if you only know Lugosi for his legendary turn as Dracula you might be surprised just how good he could be when he was able – no pun intended – to really get his teeth into a role.

As Murders in the Rue Morgue has its own disc and special features and The Black Cat and The Raven and their extras share a second disc, I’ve elected to cover the films first, then the quality of the individual transfers, then the special features that accompany each film.

| THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE |

|

| |

‘Between ingenuity and the analytic ability there exists a difference far greater, indeed, than that between the fancy and the imagination, but of a character very strictly analogous. It will be found, in fact, that the ingenious are always fanciful, and the truly imaginative never otherwise than analytic.’ |

| |

The Murders in the Rue Morgue – Edgar Allan Poe |

Back in 2007 when reviewing the luridly titled Night of the Bloody Apes, fellow scribe Gort asked a pertinent question about the once-popular horror movie notion that there was nothing in the world scarier than an ape on the loose. What in retrospect makes this seem odder still is that the apes in question were almost always a guy dressed in the sort of hairy ape suit you’d wear to a swish costume party (and as the extras here reveal, it was almost always the same performer). It could be argued, of course, that the average Joe and Josephine in the 1930s probably knew as much about apes as they did about Transylvanian noblemen and thus could be more easily convinced of the threat that they represented. But there is more to apes as a danger than their appearance and unfriendly disposition. As well as being big and dangerous-looking when riled, apes could also be seen not just as a creature from which we as a species evolved, but one that we might once again resemble if we were to regress to a more primitive and barbaric state. It’s surely no coincidence that in Rouben Mamoulian’s 1931 film adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Frederick March’s very human Jekyll transforms into an unmistakably simian Hyde.

In the 1932 film adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, director Robert Florey seems wise to the obvious fakery of ape-suited men by only shooting his man-ape in long shot and using the face of a real ape for close-ups. It’s a theoretically savvy move, removing the need for expressive masks or still-to-be-invented animatronics. But for a modern audience exposed to years of nature documentaries there’s a small issue here, as while the man-ape is clearly a big, hairy gorilla – perhaps even the orang-utang of Poe’s original story – the close-ups are of a chimpanzee, an altogether different species of ape. Nice try, but…

As I noted above, the film only bears a passing resemblance to the story on which it claims to be based. In Poe’s original, the story revolves entirely around the character of C. August Dupin and his Holmes-like investigation of the titular murders and eye for telling detail. Indeed, it has been argued that Dupin was an influence on Conan-Doyle’s rightly celebrated consulting detective, and in that respect the author of this tale functions very much as Dupin’s Watson, accompanying him on his investigations and effectively acting as Dupin’s biographer. Florey, together with screenwriters Tom Reed and Dale Van Every, with additional dialogue by a young John Huston, use this sprinkling of building blocks to go their own way with the tale. Retained are the 19th Century Paris setting, the titular murder location (including a specific detail regarding the disposal of a body), the character of Dupin (whose first name here has been changed to Pierre), the murderous ape, and a confusion over the language being spoken by an intruder. I’ll get to that comical little aside in a minute. Poe purists may balk at the liberties taken, but for the most part the filmmakers have crafted a neat and pacey little horror-tinged thriller with strong production values, an enjoyable central performance and an intriguing and forward-looking evolutionary subtext.

The film opens on the bustle of a busy fairground peppered with sideshows designed to intrigue and startle any patrons that the barkers can lure into them. Here we’re introduced to Pierre Dupin (Leon Ames, but credited here as Leon Waycoff) and Paul (Bert Roach), who are on a date with their girlfriends Camille (Sidney Fox) and Mignette (an uncredited Edna Marion). Their first port of call is a show featuring exotic Arabian dancers, salacious comments about which earn both Pierre and Paul face-slaps from their respective girlfriends. By this point conversational hints have already alluded to the fact that Pierre and Paul are medical students, and given that Pierre must be in his late twenties and Paul a good few years old than that, I’m guessing the profession was as closed to younger men in 19th Century France as it seemed to be in 1950s Britain, at least if Doctor in the House is to be believed. We later learn that both men are short on funds, but this doesn’t stop Paul from spending what money he has in order to dress like a matador for his dates with Camille.

Once the four have had their fill of the dancing girls and a show that has not aged well at all featuring Apache warriors, who are described by the barker as “bloodthirsty savages from the wilds of America,” they are drawn towards a show that features an animal called Erik the Ape-Man, “the beast with a human soul.” When the four friends take their seats in the crowded tent they treated to a lecture by a man who calls himself Dr. Mirakle (Bela Lugosi), who converses with the caged Erik in an unknown language and outrages one of the more uptight religious patrons by claiming that humankind evolved from apes, something he plans to prove by mixing Erik’s blood with that of human. I was genuinely unsure how this would prove anything of the sort, until it dawned on me – as it clearly has on more eminent film scholars – that this was the film’s way of suggesting that Mirakle’s ultimate aim is to mate Erik with a human female.

When Mirakle offers the audience the chance to meet Erik, almost everyone promptly gets up and leaves, but Pierre, Camille, Paul and Mignette and two unknown others cautiously approach the cage for a closer look at the creature. When Erik takes a shine to a bonnet worn by Camille, she is persuaded by Mirakle to hand it to him, but when Pierre foolishly makes a move to retrieve it he quickly discovers how painful a gorilla’s grip can be when applied to the throat. Mirakle balls him out for his stupidity but insists on paying for a new bonnet and asks Camille for her address so he can send one to her, and in a display of common sense that later horror films could learn from, Pierre gruffly assures him it will not be necessary and the four friends depart. Mirakle thus orders his silent assistant Janos (Noble Johnson) to follow the couple. “I must know where she lives!” he quietly proclaims. Not a good sign.

Murders of the Rue Morgue was made in 1932, two years before the Production Code – more popularly known as the Hays Code – began being more strictly enforced to clamp down on what self-righteous conservative and religious groups regarded as corrupting content in home-grown movies of the day. And if you’ve ever wondered how a Hollywood movie of such vintage could possibly have upset this gang of self-appointed moral guardians, you’ll find examples aplenty in the scenes that immediately follow the one detailed above. It turns out that Mirakle’s experiment to mix human and man-ape blood is not a proposal for future endeavours but something he’s been working on for a while without success, and being 1845 he’s not going to go about procuring volunteers by sticking posters on lampposts or placing ads in newspapers. Instead he heads out at night in a carriage driven by Janos (and in which Erik is a seated passenger) in search of potential victims. He quickly finds one in the shape of a prostitute who is being fought over by two men who manage to somehow kill each other in the process. Mirakle approaches like a man looking to lend a helping hand, but the woman is not fooled and resists his attempts to lead her away. As she is forcibly dragged to the waiting carriage, her terrified screams make it clear that she is fully aware that she is about to suffer a horrible fate. It’s a moment that sends a shudder down my spine every time I watch it, but is small potatoes compared to what immediately follows.

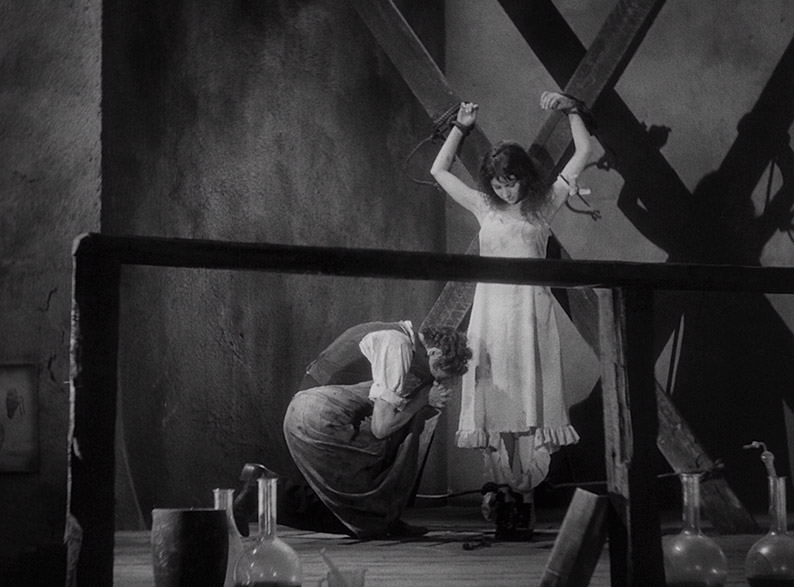

From here the film cuts to the inside of Mirakle’s lab and a shadow cast by the still screaming woman, who has been tied to an X-shaped crucifix, which Mirakle then approaches to ask if she is in pain and then assure her it will not last much longer. Those familiar with the later The Black Cat will have noted how shadow and silhouette were sometimes to suggest acts too disturbing to show on screen, but this is a pre-Code horror cinema and no sooner has Mirakle given the above assurance than the camera pans to show him cutting into the terrified woman’s arm with a scalpel (in long shot, but still…) to remove a small strip of flesh that he requires for his latest trial. Again the experiment fails and the woman expires whilst still tied to the cross, and in a moment that must have had the devoutly religious William Hays (chief enforcer of the Production Code, after whom it was nicknamed) shaking his interfering fist at the screen, the despairing Mirakle curses the crucified woman's poinsoned blood (a reference to venereal disease, perhaps?), then kneels at her feet, clasps his hands together and seems to offer up a prayer for his endeavours. Given the woman’s profession, it’s an image that I have little doubt was seen as sacrilegious in its day.

That Camille will eventually be targeted by Mirakle and Erik is inevitable given that both man and man-ape seem captivated by her and that Mirakle is now fully aware of where she lives. Those familiar with Poe’s story will likely be able to take a fair guess at how subsequent events unfold and they’d be partially correct, and while the outcome is significantly altered for the film, one of the more gruesome details has been surprisingly retained (I’m trying to avoid spoilers, so can’t really say more). A little perversely, the sequence that is probably most faithful to the source material is also for me the film’s only significant misstep, with confusion about the language spoken by an intruder turned into an Abbott and Costello-like comedy routine. It’s not the effectiveness or otherwise of the humour I have issue with – such things are a matter of taste, after all – but its placement slap-bang in the middle of the tension-fuelled build-up to the climactic scene, putting the drama unexpectedly on pause for a disorientating shift from drama to comedy and back again.

Given an expressionist undercoat by French director Robert Florey (there are several small nods to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) and sharply edited by Milton Carruth (two fast-cut montages of watching faces have an almost Eisenstein feel), the film also looks terrific, thanks in no small part to Frankenstein and Dracula art director Charles D. Hall’s expressive sets and sometimes striking lighting camerawork by master cinematographer Karl Freund. Freund occasionally gets to fire on all cylinders here, bolting a camera to a swing to stay locked on Camille as she gaily drifts back and forth (given the size of sound-shielded cameras in the day, I can’t help wondering what the rig to effect this shot must have looked like), and swooping up from a jealously watching Mirakle to a balcony on which Camille and Pierre are canoodling and back again in the manner of F.W. Murray in his silent heyday.

But the key attraction is definitely Bela Lugosi, who here shakes off the ghost of his signature role as Count Dracula in a performance whose theatrical quality is most appropriate for the role and captivatingly nuanced in places. His intolerance when speaking to a visiting Pierre certainly comes from the heart, and when accused by a pious audience member of heresy, he delivers a splendidly written response with deliciously calm and self-confident relish – “Heresy? Heresy? Do they still burn men for heresy? Then burn me, monsieur. Light the fire. Do you think your little candle will outshine the flame of truth?” Indeed, it’s in the passionate delivery of his evolutionary message (one that Pierre, it should be noted, remains sympathetic to) that Mirakle is at his most likeable, seemingly goading his morally uptight audience and the more religious enforcers of the Hollywood establishment alike with his devotion to what would, within the timeline of the film, later become Darwinian theory. There’s also a sly nod to humankind’s development when he responds to Erik’s chattering by asking his audience, “Can you understand what he says? Or have you forgotten?” It’s one of many small but rather delicious details in a film that plays even better than I remember, and one I’d frankly be happy to buy this set for alone. But there’s more…

| |

‘For the most wild, yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief. Mad indeed would I be to expect it, in a case where my very senses reject their own evidence. Yet, mad am I not – and very surely do I not dream. But to-morrow I die, and to-day I would unburthen my soul. My immediate purpose is to place before the world, plainly, succinctly, and without comment, a series of mere household events. In their consequences, these events have terrified – have tortured – have destroyed me.’ |

| |

The Black Cat – Edgar Allan Poe |

Even by the standard of these early Universal film adaptations of Poe’s celebrated short stories, the 1934 The Black Cat, directed by Edgar G. Ulmer and adapted by Ulmer and Peter Ruric, has only a gossamer link to its source material. They both feature a black cat. That’s about it. Indeed, the opening title credit stating that the film was “suggested by the immortal Edgar Allan Poe classic” contains only a sliver of truth, the sliver in question being that the studio knew the story and presumably wanted to trade on the name recognition of its title. Not that they needed to with the first pairing horror cinema’s two most famous stars to splash across the posters and billboards. Yet despite the decision to dispense with Poe’s words and go its own way with a title that may or may not have been attached to the project from the start, the film is still a gripping and most impressively creepy little horror-tinged thriller.

Newly married Peter and Joan Alison (David Manners and Jacqueline Wells) are on their honeymoon in Hungary and travelling by train to the town of Visegrád, and from there by bus to the municipality of Grunmbach. They have a private compartment and are planning to enjoy each other’s company for the journey (there’s a discussion about dinner that has just a whiff of sexual metaphor about it) when the conductor sticks his head in and apologetically informs them that the compartment has been double-booked and that another passenger will be joining them after all. The man in question is Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Bela Lugosi), a prominent Hungarian psychiatrist who has spent the previous 15 years in a Russian prison camp that he was sent to after being captured during the First World War. He is returning to Grunmbach to confront Hjalmar Poelzig (Boris Karloff), a now celebrated Austrian architect who during the war commanded Fort Marmorus, on whose ruins he now lives in a house of his own design. Werdegast believes that while commanding the fort Poelzig betrayed his country, which resulted in the deaths of ten thousand Austro-Hungarian soldiers. The three are on amiable terms by the time they reach Visegrád, but when the subsequent bus carrying Peter, Joan, Werdegast and his manservant Thamal (Harry Cording) crashes in stormy weather, the driver is killed and Joan is knocked unconscious. The three surviving and relatively unharmed men rescue Joan from the wreckage and carry her to Poelzig’s house, where Werdegast tends to Joan’s injuries and finally comes face-to-face with the man who not only presided over the deaths of thousands, but who stole his beloved wife and daughter from him while he was imprisoned.

For horror fans coming to The Black Cat for the first time, the film has a sprinkling of surprises in its opening scenes alone. The first, for me at least, is that romantic lead David Manners is instantly more engaging than he was as cinema’s dullest Jonathan Harker in Tod Browning’s Dracula. The second is that Werdegast, despite early subtle suggestions to the contrary, soon develops into the film’s most sympathetic character, a rare good guy role for Lugosi, who for my money gives what may be his finest performance in this film. The third comes when the party reaches Poelzig’s house, which after a stormy night build-up worthy of The Old Dark House, turns out not to be the gothic mansion of genre tradition but a brightly lit modernist abode that must have looked almost futuristic back in 1934. It makes sense, of course, Poelzig being an architect of considerable renown, but still catches you by surprise in a horror film of this vintage. There are other unexpected turns later, but they take us into spoiler territory and I’ll thus be throwing up a warning before getting into them in any detail.

Poelzig’s abode may be modern but Poelzig himself has all the traits of a classic horror movie villain, from his sharply angled widow’s peak to his slow deliberate movements and his penchant for silent and sinister glares. It’s a performance that initially plays far more to 1930s genre expectations than Lugosi’s far more subtle and nuanced portrayal of Werdegast, but which quickly loosens up when Poelzig is playing host to Peter, and later Karloff effectively conveys the haunted nature of the man that lurks beneath his icily cold and calculating surface.

Despite its modernist sheen, lurking within his house really are a number of genuinely disturbing secrets, some of which are directly connected to the reason for Werdegast’s visit. I should note that when I say disturbing I’m not just talking about how the film must have played in its day. The Black Cat was released on the cusp of the more strict enforcement of the Production Code, and thus includes sequences, moments and plot elements that I can’t believe would have been given the green light just a couple of years later (and if you’re new to the film and want to avoid even a whiff of spoilers then hop ahead to the next paragraph). These include a gallery in which the preserved bodies of sacrificed young virgins are displayed in glass cabinets in which they appear to be floating, as haunting an image as any in Universal’s horror output of the period. We also have what may be the first full-on Satanic ritual to appear in a Hollywood movie (complete with an inverted Patriarchal cross that is used as an altar) and a scene in which a character is flayed alive, which although captured briefly in shadow still has the power to startle the unprepared. The nature of Poelzig’s interest in Joan, meanwhile, is captured in two simple but effective moments, the first when the sight of her kissing her new husband prompts him to tightly grasp a statuette of naked woman, and later when a lascivious look he throws in her direction prompts her to quickly grasp the lapels of her nightdress and cover her chest. Earlier on the train to Visegrád we are misdirected to suspect that Werdegast has similar designs on Joan when he reaches out to touch her hair while she sleeps. When he is spotted by a waking Peter he apologises and explains away his action by revealing that Joan, a short-haired brunette, is the image of his beloved wife, whom we later discover is a long-haired blonde. This is one of the few signs of the reshoots that were ordered by studio head Carl Laemmle Snr. following his outrage at the film’s apparently even more brutal original cut.

As I noted above, despite the complete deviation from Poe there is at least a black cat in the film, albeit one whose only purpose is to trigger Werdegast’s ailurophobia at a critical moment and – a little too conveniently, though less so if you apply a semi-supernatural reading – allow a story that would have been otherwise cut short to play out to its impressively grisly climax. Poe purists may balk at the notion of a film that nicks its title from Poe and credits the author, but then dispenses with the story to tell its own tale, but I personally have no problem with that if the resulting film delivers on story and chills, and The Black Cat certainly does that. Lugosi is terrific here, Karloff is devilishly sinister, an alluring Jacqueline Wells screams and faints on cue, Charles D. Hall’s production design is consistently eye-catching, later plot twists pack an appropriate punch, and the horror, when it comes, is genuinely chilling. What really surprises, however, has less to do with what is depicted than what is grimly suggested and only really registers after the film has concluded. I also couldn’t help but smile at the revelation in the extras that this content and further originally scripted horrors were included partly at the behest of then 26-year-old producer Carl Laemmle Jr. just to piss off his more conservative dad.

| |

‘Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!”—

Merely this and nothing more.’ |

| |

The Black Cat – Edgar Allan Poe |

If the complete deviation from Poe on The Black Cat was a touch surprising, the fact that the plot of the 1935 The Raven bears next-to-no relation to the poem from which it ostensibly draws its inspiration is considerably less so. Frankly, I can’t imagine anyone fashioning a feature-length mainstream film from what may be Poe’s most celebrated work, even one running for just an hour in length. The connection to Poe is certainly stronger here than it was in The Black Cat, but in common with the other Poe adaptations in this set, the filmmakers have borrowed the title and then gone their own sweet way with the plot.

When Jean (Irene Ware), the beautiful daughter of the esteemed Judge Thatcher (Samuel S. Hinds), is critically injured in a car accident, her medical team reveals that the operation required to restore save her life can only be performed by retired surgeon Dr. Richard Vollin (Bela Lugosi). When they phone him, however, he has no interest in taking the case. Thatcher thus jumps in his car and scoots on round to Vollin’s house, where his personal pleas also fall on deaf ears, but when he persists Vollin eventually acquiesces and successfully performs the operation. A few weeks later Vollin entertaining the fully recovered Jean at his house and has clearly developed a serious crush on her, one she initially shows signs of reciprocating but that is cut short by her interfering father because she’s already engaged to a square-headed dullard of a doctor named Jerry Halden (Lester Matthews). This doesn’t sit well with the love-struck Vollin, and when notorious gangster-on-the-run Edmond Bateman (Boris Karloff) shows up at his door looking to change his appearance via plastic surgery, he devises a scheme to take revenge on Thatcher and claim Jean for himself by disfiguring Bateman in a surgical process that he agrees to reverse only if he assists him with his diabolical plan. And Vollin is a man whose obsession with the works of Edgar Allan Poe has prompted him to construct some of the torture devices outlined in Poe’s stories in the basement of his luxurious house...

Although made and released a year after The Black Cat, there’s almost a sense that for Karloff and Lugosi the two films were mirrored companion pieces. In the first Lugosi played the sympathetic victim and Karloff the monster in human form and here the roles are reversed, right up to how each affects the other’s ultimate fate. There’s even a musical signifier of this role change in the shape of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, which is played on the organ by Karloff in The Black Cat and by Lugosi in The Raven. Where Karloff paints Poelzig in sinister colours from the moment he makes his first appearance in The Black Cat, however, here Lugosi plays Vollin as a well-to-do man who is gradually driven to madness by his obsessive desire for something he can never have. That he is emotionally aloof and ego-driven is established from the off by his casual disinterest in saving Jean’s life and the fact that he only agrees to do so when he learns that his former colleagues have proclaimed him the only one skilled enough to perform this delicate operation. When Thatcher later puts a firm stop to Vollin’s romantic pursuit of Jean it thus comes as an affront, an ungrateful about-face on the judge’s part and made worse by the knowledge that jean has chosen instead to marry one of the lesser skilled doctors who so proclaimed Vollin in the first place. When it comes to saving Jean’s life, Vollin is Thatcher’s man, but when it comes to romancing his daughter, well, he thinks she can do better. What a git. Vollin may be the film’s bad guy, but at this moment I was absolutely in his corner. Of course, it probably didn’t help that the surname of his new nemesis is Thatcher...

It’s noted more than once in the extra features that despite Karloff’s top billing and far higher salary, Lugosi is very much the star of the show here and for much of the running time Bateman is effectively a supporting character. That’s not to take anything away from Karloff’s fine performance and his ability to evoke sympathy through facial expression alone, and the surgical fate that he suffers is also the point at which my sympathy for Vollin evaporated and I began hoping Bateman would instrumental in his demise. Lugosi is once again on enjoyable form here, splendidly sadistic when verbally torturing the imprisoned Bateman from the safety of a high window, effortlessly charming when regaling his dinner guests with his interpretation of Poe’s titular poem, and really relishing his steady downward slide into madness.

While much is implied, there are no scenes that startle for their day in the manner of those in The Black Cat and Murder in the Rue Morgue, and the one shock moment when the results of Bateman’s operation are revealed is undercut just a tad by the inevitability of what Vollin has done and one of makeup master Jack Pearce’s less convincing facial transformations. Ultimately it’s Karloff’s confusion and despair that sells it, and I can’t be the only one for whom the removal of the bandages to reveal the horror beneath has later echoes in a key scene in Hammer’s breakthrough horror work The Curse of Frankenstein. It’s a connection emphasised, of course, by the fact that Karloff first shot to fame playing the creature in Universal’s take on the Frankenstein story, and is brought home further by the Bateman’s furious growls, which are almost identical to those delivered by Karloff as the Creature in James Whale’s film.

The whole thing move at a fair lick thanks to breezy direction from Lew Landers (here working under his real name of Louis Friedlander), a busy director who would later reunite with Karloff for the 1942 horror-comedy The Boogie Man Will Get You, and Lugosi for the 1943 The Return of the Vampire. Albert S. D’Agostino’s art direction delivers a convincingly scary bladed pendulum that was likely the blueprint for the even more alarming one in Roger Corman’s later take on that particular Poe tale. Charles J. Stumar’s cinematography may not have the eye-catching flourishes of Karl Freund’s work on The Black Cat, but he and his director still pull one neat trick by creating the sensation of an elevator-sized room’s descent by simply raising the camera slowly within it. The Raven is a great deal of sinister fun, and watching it again I couldn’t help wondering if, given that he turned down the role of the Creature in Frankenstein, Lugosi quietly relished playing a character who transforms his horror rival into a monster, but in a manner that destroys his life instead of making his career.

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

Judging from how it looks here, I’m guessing that Murders of the Rue Morgue has undergone a full restoration, because the 1080p 1.37:1 transfer on this Blu-ray is a wonder to behold. There is a small amount of brightness flickering and the occasional tiny dust spot and scratch, but in all other respects the quality of the image belies the film’s age. Detail is crisp, the black levels solid, the contrast sublimely balanced and the picture largely clean and stable in frame. Seriously, if I’d come to this fresh and was told that it was filmed recently in the style of a 1930s horror movie, I’d probably have believed it.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has the sort of restrictions to the dynamic range that you’d expect from an early sound feature (no bass, slightly hissy trebles), but is otherwise clean, with clear presentation of the dialogue. A level of background fluff is just audible if you have the volume high.

Apart from the title sequence extract from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (a signature feature of early Universal horror films), there is no music in the film as it originally screened, though at a later date music was added to some scenes by anonymous philistines at Universal. Pleasingly, this Blu-ray includes both versions. Even more impressively, if you elect to play the version with this alternate soundtrack, a caption advises those new to the film to watch the one with the original soundtrack first, a sentiment with which I heartily concur. The added music is not bad in itself but still feels a bit wrong, being of a higher audio quality than the rest of the soundtrack and including electronic instruments that completely divorce the score from the film’s year of production. Go with the original.

THE BLACK CAT

After the visual deliciousness of Murders in the Rue Morgue, the 1080p 1.37:1 transfer of The Black Cat feels a tad less stellar, but is still very impressive in many respects. The image is sharp and the detail clearly rendered, clearly enough indeed for me to be able to easily spot when a lens diffuser was used to give Jaqueline Wells a more romantic sheen in close-up. Contrast is well balanced, with solid black levels and a good tonal range when the light levels allow, and a fine film grain is visible throughout. The image is generally clean, but there are still a fair few dust spots and small traces of damage, plus a degree of brightness flickering in places. Occasionally, the image also twitches a bit in frame (notably at the tail end of dissolves), but on the whole this is still a very good transfer.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has the expected range restrictions, but the dialogue is clear and the music, though a tad shrill a times, never distorts. There is some low-level background fluff in quieter scenes, but you’ll need to have the volume pumped up to really hear it.

THE RAVEN

The 1080p 1.37:1 transfer here, which was created from the original film elements, is also solid in many respects, though detail is noticeably softer than on the other two films in this set. At its best this still a very serviceable job for a film of this vintage and intermittently it really comes into its own – the written text on a close-up of an invitation sent by Vollin to Jean is crisply rendered – but just occasionally the image looks almost as if it has been upscaled from a standard definition print. This is largely confined to the early scenes – in a wide shot of Jean’s dance interpretation of The Raven on theatre stage, the faces of the two performers are blurred beyond easy recognition. In other the respects the transfer is fine, with decently balanced contrast, almost no movement of the picture within the frame, very few dust spots and a fine film grain, albeit one that is considerably coarser in the opening night time footage. It’s also in the early shots that traces of former scratches are at their most visible. On the whole, it’s still a very decent job and I’d probably be rating it even higher had I not watched the other two films first.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has the anticipated limits to its dynamic range, which particularly impacts the music score, but is otherwise in good shape, with clear rendition of dialogue and no distracting background hiss or damage. If you like the music, then you’ll be pleased to know that it’s in considerably better shape on the included isolated music and effects track, which is also Linear PCM 2.0.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included on all three films.

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE

Audio Commentary by Film Historian Gregory William Mank

An engaging blend of factual information and thoughtful analysis from film historian and author Gregory William Mank, whose books include the very pertinent Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration. We get details on the production and the post-release censorship problems, plus info on the cast, including quite a bit on Sidney Fox and John Bonomo, a man who made quite a career for himself playing gorillas in movies of the era. Comparisons are made to Poe’s original story, and the order in which the scenes were originally scripted to run is also usefully outlined. There’s plenty more of value here. Good stuff.

Kim Newman Interview (28:49)

Dressed in a splendidly colourful waistcoat plastered with images of horror movie posters, the venerable Kim Newman provides a detailed overview of all three films in this set with an enthralling mixture of factual information, analysis and personal opinion. I found myself in complete agreement on a number of points – including the misjudged comedy sequence in Murders in the Rue Morgue and he belief that The Black Cat gave David Manners his best film role – and I almost did an “of course!” forehead slap at his spot-on suggestion that Poelzig in The Black Cat, with his evil plan and modern gadget-filled house, is almost a prototype for Bond Villains to come. There’s loads more here, enough to make it worth saving until after you’ve watched the films themselves.

Bela Lugosi Reads The Tell Tale Heart (13:21)

A wonderfully committed and appropriately creepy reading of Poe’s celebrated The Tell Tale Heart by Bela Lugosi, whose accent and delivery really make it feel like the demented confession it was written as. The accompanying crackles suggest this was sourced from a vinyl record, but the voice is always clear and the wear and tear oddly add to its air of a recently discovered and long-lost document of self-incrimination. I enjoyed the hell out of this.

Trailer (1:35)

“Only Poe dared imagine it! Only people who can stand excitement and shock should dare to see it!” scream the final captions on this nicely creepy trailer that makes effective use of silence and screams rather than plastering the chosen clips with music.

Stills Gallery

31 screens of high quality still, posters and press ads for the film and specific screenings.

Easter Egg

I almost missed this one, but it's an absolte doozy that I only discovered when grabbing stills on my computer for inclusion in this review. If you want to find it yourself then skip to the next paragraph. On the main menu, move the cursor down the list of options to Stills Gallery, then instead of pressing Select, press left on the remote and you'll select the title of the film, which sits large on the left of screen (a subtle colour change will indicate you have it). Now press Select and a screen of text will appear introducing an alternative cut of the film based on the rearrangment of some scenes into their originally intended order, which is briefly discussed on Gregory William Mank's commentary track, but covered in more detail in the accompanying booklet. This reordering of the opening scene especially impacts greatly on how you react to Mirakle at his carnival sideshow, as in this version we've already seen the body of one of his victims retrieved from the river and watched the scenes in which he kidnaps and cuts the skin from the terrified prostitute. When he smiles at the arriving party of four in tis edition, the effect is now genuinely chilling. There are a number of other changes, but these are worth discovering for yourself, ideally after you've watched the release cut. I think I actually preferred this reordered version.

THE BLACK CAT

Commentary by film historian Gregory William Mank

Film historian and author Gregory William Mank is back for a second commentary, which like the one by Gary D. Rhodes on The Raven, appears to have been sourced from the US Scream Factory Blu-ray box set, Universal Horror Collection: Vol. 1, which explains the mid-commentary promotional push for that release and the other volumes that followed. Not that I’m complaining, as Mank once again delivers the goods with another well-balanced mixture of factual information, analysis and personal opinion about a film that was apparently a favourite of Lugosi’s, and it’s not hard to see why. Mank quotes from the original script to give an idea just how much more gruesome the film could have been and how different Lugosi’s character was as written – originally, he was meant to be as Werdegast was meant to be as evil a Poelzig. He identifies riskier elements that are alluded to rather than spoken out loud, and has some sobering tales about director Edgar G. Ulmer’s treatment of actor Lucille Lund after she rebuffed his advances – the #MeToo rebellion was still a long, long way off then. Once again, this is just the tip of the information iceberg, and you’ll likely learn a lot from this most informative extra.

Cats in Horror (12:47)

Less a definitive look at the role of cats in horror film history (almost all of the films covered are British or American and there’s not a mention of the Japanese ‘ghost cat’ sub-genre) than an examination of a select few lesser-known titles in which vengeful or sinister cats are featured, including The Cat Creature (1973), The Uncanny (1977) and Strays (1991), and few will be surprised that both adaptations of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary also get some coverage. Definitely interesting, but I’m guessing this was recorded by Gambin himself during whatever lockdown is in place at his home base, which is probably why the recording is peppered with sometimes loud bass bumps to the microphone or the table on which it is sitting.

The Black Cat Radio Adaptation (26:02)

Peter Lorre stars as the increasingly mad protagonist of Poe’s original story, which is faithfully adapted (though the gouging of the cat’s eye in Poe’s tale has been unsurprisingly replaced by an angry assault that results in a torn ear) for this 1947 radio play broadcast as episode of 12 of a series titled Mystery in the Air. It’s an enjoyable listen, not least for Lorre’s increasingly unhinged portrayal, though the broadcast itself is seriously dated by its enthusiastic sponsorship message of the benefits of smoking Camel cigarettes.

Vintage Footage (0:49)

Valuable archive footage of Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff judging a black cat competition open to children with such animals for pets and staged to promote a film that children would likely have been discouraged from seeing. One cat in particular seems keen to pick a fight with its nearest neighbours and frankly should have been signed up immediately for film work.

Stills Gallery

A misleading use of a plural in the title for a gallery that – unless my review disc is faulty – appears to contain only a single still of Werdegast and Poelzig playing chess for Joan and Peter’s freedom.

THE RAVEN

Audio Commentary by Film Historian Gary D. Rhodes

Film historian Gary D. Rhodes, who is also the author and co-author of several books on Bela Lugosi and his films, acknowledges the difficulty facing anyone looking to adapt Poe’s poem into a feature and notes that almost all early adaptations of the author’s work have had to alter or build on the story in some way. He notes that in Vollin we have what is probably the first portrayal screen of a horror fan, goes into detail about objections raised by the Production Code office, provides quotes from contemporary reviews and the written responses of theatre managers, and confirms that the notion of 30s gangsters seeking plastic surgery to alter their appearance was not in any way fanciful but drawn from headlines of the day. Although he loves the film he’s not above pointing out the odd plot inconsistency and expresses disappointment at Karloff’s face distortion makeup, but has many good things to say about the performances of the two leads. Once again, great stuff.

Audio Commentary by Samm Deighan

A second audio commentary, this time featuring Diabolique magazine’s Samm Deighan, appears to have been recorded specifically for this release and really compliments the one detailed above. Deighan really knows her classic horror cinema and is a mine of information on this and other related genre films, particularly Kiss of the Vampire, which gets a strong recommendation here and a big thumbs-up from me. She describes The Raven as more of a mad scientist movie than a straight-up horror work and links that to earlier examples of this sub-genre and other mad scientist roles played by Lugosi. There is also plenty of info on the key cast and crew members, as well as a look at what makes Lugosi and particularly his performance here so enjoyable to watch. Another very fine extra.

American Gothic (14:59)

Illustrated by appropriate clips and graphics, the voice of Kat Ellinger, an always welcome mainstay of recent British independent Blu-ray releases, takes us on a journey through American gothic literature and looks at the problems of adapting Poe for the screen, with special focus on two of the films from this set.

The Tell Tale Heart Radio Adaptation (26:42)

Boris Karloff stars in a loose adaptation of Poe’s celebrated tale, which was originally broadcast on 3 August 1941 as episode 31 of the Inner Sanctum Mystery series. The original is essentially a confessional monologue and has been reinterpreted here as a drama and altered to make the protagonist seems a little more sympathetic, providing some justification for a murder that in the original was committed simply because the killer didn’t like the appearance of a kind old man’s eye. Enjoyable, but I still prefer Lugosi’s more faithful reading of the story.

Also included is a a typically excellent Booklet opens with credits for all three films, then moves on to a detailed and enjoyable essay on the movies and Lugosi by Australian film critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who also explores the variations on the mad doctor/scientist roles Lugosi plays here. Next is a welcome and impressively thorough piece by critic and author Jon Towlson on the making and censoring of The Black Cat and The Raven. Following this is an article on the rearranging of scene order in Murders in the Rue Morgue, which opens with an extract from Gregory William Mank’s book Karloff and Lugosi: The Story of a Haunting Collaboration before moving on to scans from a Video Watchdog article that proposed a hypothetical director’s cut of the film. This is joined by the a letter sent to the magazine by Gary L. Prange offering corrections to scene order listed in the article, plus liner notes written by Prange about the assembling of this ‘reconstructed’ version that were originally handed out at an unspecified WonderFest.

Terrific. Three classic Universal horror films, all looking great (and one looking superb), backed by a slew of excellent and informative special features. Revisiting them all after many years, it was The Murders at the Rue Morgue that grabbed me the most (as time was running out, I actually cut my proposed review short), but the more I watched The Black Cat, the more I considered it its equal, not least for Lugosi’s terrific central performance. A splendid release that can’t help but whet the appetite for a couple more box sets of this sort. Just a thought. Highly recommended.

|