|

It's interesting to look back at the work of any filmmaker of note and try and spot the film in which the elements we tend to think of as defining their work can be seen to be fully formed. In the case of more recent directors who have made a Sundance splash at the start of their career, these can often be seen in their first film, but with older auteurs who may have started out jobbing for studios on any project that allowed them to sit in the director's chair, it's not so clear cut. There's an interesting extra on the Blu-ray release of Roy Andersson's A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, which takes a trip through this singular director's career via extracts from his films. While this may sound a little superficial, especially as it's not being backed up by interviews or narration, it does allow us to pinpoint the exact moment that Andersson discovered the unique approach to film storytelling that later gave us Songs From the Second Floor, You, the Living and, of course, A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence.

So what of Robert Altman? There are certain elements that tend to define an archetypal Altman film, if there can be said to be such a thing. But Altman was not an indie director who caught the eye of a studio boss in search of budding new talent – like a number of his contemporaries, he started out directing documentaries and industrial films before moving into television. His first fully fledged feature was the 1967 low budget science fiction feature Countdown starring a youthful James Caan and Robert Duvall, a project from which he was ultimately fired for refusing to cut the film down to the studio required length. I think it's fair to say that if his name was not up there on the opening credits, you'd be seriously pushed to peg this as a Robert Altman film. Two years later he directed M*A*S*H, which effectively set the style for many of the most celebrated Altman films to come, but shortly before this he made That Cold Day in the Park, an intriguing, unsettling and distinctly offbeat, slow-burn psychological drama that was a box-office and critical disaster on its release. You think I'm exaggerating? Try this from the New York Times: "If there is a sicker, and more tedious, overbaked and inane serving of psychosexual nonsense this season than That Cold Day in the Park, it will have to go far to beat the Sandy Dennis vehicle that opened yesterday at the Orleans and Plaza Theaters." Wow. Like Countdown, That Cold in the Park is not instantly recognisable as a Robert Altman film, at least in the manner that M*A*S*H unquestionably is. But there are still elements here, in his handling of group scenes and even the camerawork, that it would be accuarte to describe as 'Altman-esque'. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

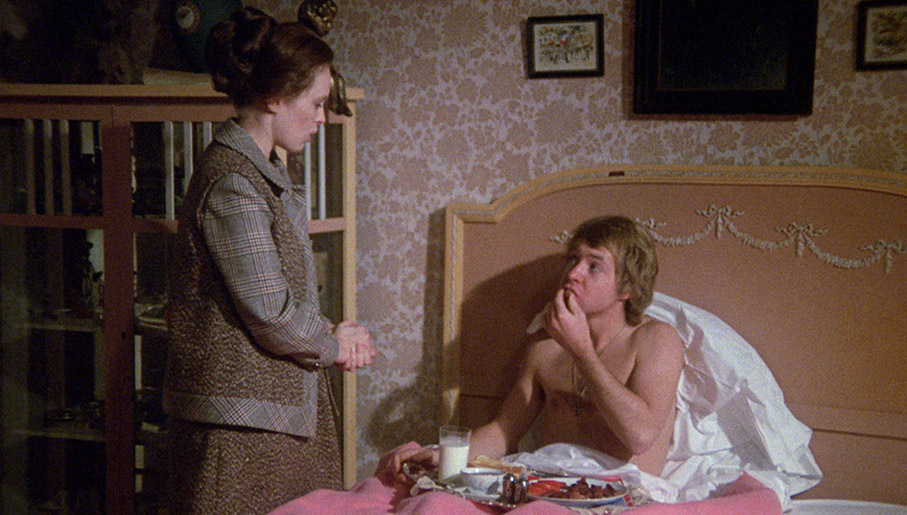

The story here revolves around Frances Austen (Sandy Dennis), a well-to-do, 30-something spinster whose life appears to be empty of purpose and meaningful companionship. She hosts dinner parties in her Vancouver apartment for her older wealthy friends, but seems somehow distanced from them and unfulfilled by their company and conversation. Before and during the course of her latest social gathering, her eye is repeatedly caught by a young man (Michael Burns) sitting on a bench in the park below. Hunched against the cold, he stays in the same spot even when it starts to rain, for which he is ill-prepared. When Frances expresses concern for the boy's welfare, her friends are dismissive in that way that society people tend to be when pestered by news that someone poorer than themselves may be having a hard time. When her guests depart, Frances calls the boy over and invites him inside to shelter from the rain. She feeds him, lets him take a bath and dries his clothes. She also talks to him constantly, but the boy remains silent and regards her with looks of curious uncertainty. Eventually she persuades him to stay the night and even brings him breakfast in bed the next morning, and still he says nothing. Is he unable to understand what she is saying or has he simply lost the power of speech? And if he does understand, what are his intentions? And what of Frances? Has she become so lonely that she is blind to the potential danger the boy she knows nothing about might represent?

Plenty of questions there, but here's another one: just how much should I reveal about what happens next? Ideally nothing. That we will eventually discover what's going on seems likely from an early stage, in spite of just how long this first and largely one-sided encounter plays out for, but the process of revelation is something best experienced by watching the film. Yet to talk about some of its more interesting aspects requires delivering at least one spoiler. So if you want to go in cold then I'd hop to the final paragraph of the main review, which you can do by clicking here. For those that remain, note that there be a spoiler ahead. Not a film-busting one, but a spoiler nonetheless.

I'll admit up front that Altman does push his luck how long he has Frances play host to this uncommunicative, almost child-like young man before he moves the story into its second act. But in doing so he cements the idea that the boy (whose name we never learn) really is either mute or cannot understand a word Frances says and is too bemused by her actions for any reciprocal attempts at verbal communication, which makes the rug pull that follows all the more effective.

It starts when Frances bids the boy goodnight at the end of their second evening together and leaves him to sleep, and on her departure he quietly dresses, hops out of the window and makes his way down the fire escape. Two surprises follow, both based on the perception that our first half-hour of exposure to the boy as a silent and friendless loner have helped to form. In the first the boy drops in on what we quickly realise is the family home, a hive of activity that the boy cheerfully becomes part of as if he's been there all evening. Fascinatingly, this entire sequence is observed from outside the house in a single crane shot that glides gently up and down to follow the boy as he interacts with relatives on different floors of the building. It's a cannily handled scene, as from this restricted viewpoint it's hard to be sure if he says anything to any of them – they certainly talk to him and do not appear bothered by his (apparent) lack of verbal response.

A short while later he enters a run-down shack and walks in on a woman in the throes of sexual activity. She angrily orders him out, and he sits silently on the steps outside while she finishes her business before being invited back inside. Again it's the woman – who turns out to be the boy's sister – who initially does the talking, but a short while later the boy is chatting away to like he's never had a quietly contemplative moment in his life. So what is going on? Well here's where the spoilers really do have to stop. Over the course of the conversation between the boy, his sister and his sister's boyfriend, we are given plausible reasons for and why he was sitting alone in the park and for his earlier silence (well, sort of), and also learn a thing or two about his social situation.

The boy's departure, when discovered, clearly disappoints Frances, but when he shows up at her door the next day bearing edible gifts, the two look set to pick up just where they left off. Just where is this going? Certainly, what we (but not Frances) have subsequently learned can't help but alter our perception of the situation and suggest that Frances is naively setting herself up for an emotional fall at the hands on a long con being played by her young guest. But is all as it seems here?

We're well into the film before the narrative tables are turned, so to speak, and whether you buy in to this may well depend on whether you've picked up on the numerous clues to its eventuality dropped along the way, and indeed whether you feel they qualify as clues at all. If you don't then you're looking at a behavioural shift whose inexplicability was one of the things that so irked those early reviewers, particularly as little attempt is made to dig beneath the surface and explore the true motivation for what unfolds. For those of us raised on horror movies (and that doesn't mean I'm claiming this is a horror movie, because it isn't), a genre in which rarely lets psychology get in the way of a good story twist or scare, this is unlikely to be an issue, and on a second viewing the signs and the precise trigger point for a later behavioural shift are more clearly evident.

While this may not sound like your usual Altman fare, it does point the way to his 1972 Images, a more overtly horror-tinged psychological thriller starring Susannah York as a woman haunted by hallucinations linked to sex and death. And there are elements of the handling here that have Altman's stamp all over them, from drifting camera moves and zooms into mid-shot or facial close-up (and at one point past Frances and into abstract patterning) to the overlapping dialogue and improvisational feel of the group scenes, soon-to-be signature techniques that would find their perfect outlet in M*A*S*H two years later. And there are interesting experiments in film storytelling elsewhere, with the through-the-windows crane shot briefly discussed above taken a step further when Frances visits a clinic to have a diaphragm fitted, which is viewed exclusively from outside the building, the soundtrack busy with overheard discussions about sex and contraception, putting us inside Frances's head even as we observe her from the viewpoint of a curious voyeur. And yes, that's soon-to-be Altman regular Michael Murphy in small but memorable role that I'm not about to add to my spoiler crimes by outlining here.

Camus recently observed that M*A*S*H is a film that has next to no story and is actually comprised of a handful of character arcs that play out over the course of a series of loosely connected and richly entertaining vignettes. And it works, sublimely. That Cold Day in the Park is also light on story, but being primarily focussed on just two characters and comprised of scenes that are driven largely by conversation – much of it one-sided – the narrative dilution is more keenly felt here, though given that it plays primarily as a two-handed character study, I'm not sure this really matters. As he would continue to be from this point on, the director is well served by his cast, particularly Sandy Dennis, whose delicately handled portrayal of Frances really does reward a second viewing, where the small signs of the direction events will later take are teasingly visible but never overstated. Some will doubtless share the views of the film's early detractors and find it trite and boring, but I'd hope that the wider range of cinematic storytelling to which we've been exposed since the late 1960s would allow the film to find a more receptive audience now. And while I'm not looking to champion it as a previously overlooked Altman masterpiece, That Cold Day in the Park is still a fascinating and unsettling early work from a director who at this point was still honing the style that would come to go on to define him as one of the key maverick filmmakers of modern American cinema.

When I first got my eager hands on the DVD of M*A*S*H I remember my disappointment at the picture quality, which felt muddy and a little soft when stood alongside other transfers of American studio films of the period. It took a while to dawn on me that part of this was down in part to a chosen aesthetic, and there's more than a whiff of that look to the 1.78:1 HD transfer here, giving some scenes a slight softness that makes them feel almost as if they were shot through a light haze filter. But odd though this may sound, this actually works well for the scenes in question, and in all other respects the transfer is on the nose, with nicely pitched contrast, solid blacks that do not suck in surrounding detail and solid reproduction of the film's earthy colour palette. When the conditions are right (check out the cardigan worn by a woman in the late bowling scene) the level of detail is also impressive. Grain is sometimes very visible, but the image is clean and stable throughout.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is a little range restricted but clean and free of any damage or noise and with very clear reproduction of the dialogue that drives the narrative.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

David Thompson on That Cold Day in the Park (28:16)

Celebrated critic and enthusiast for the film, David Thompson, provides a useful overview of Altman's early film and television career before focussing on That Cold Day in the Park, revealing details of its production (Ingrid Bergman was Altman's first choice to play Frances but was apparently disgusted by the script and shocked that he would ask her), outlining the differences between the film and the source novel, and providing an analysis of Altman's handling that picks up on some of the very same things that I'd already noted in my humble coverage. Ain't that always the way? A really worthwhile extra.

Booklet

Another top flight Masters of Cinema booklet, this one featuring a fascinating analysis of the film and its lead character from Australian critic, writer and academic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, an article on the making of the film from a 1969 issue of Motion Picture Herald, a 2003 essay on the use of Vancouver as a film location by David Spaner, a short but valuable piece by Altman himself on lead actor Sandy Dennis, credits, viewing notes and stills.

While not exactly a defining Altman film, That Cold Day in the Park is still a must-see for fans of this most singular filmmaker, peppered as it is with distinctive and inventive directorial touches and bolstered by a strong but not attention-grabbing performance from Sandy Dennis. It paves the way for later films like Images and Three Women and looks pretty damned fine on this Masters of Cinema Blu-ray. Recommended.

Additional note: That Cold Day in the Park will be available to stream on the Arrow Player from 8 April 2024.

|