|

When it comes to how quickly I engage with a film, I tend to be a bit of a cine-contrarian. If the movie I’m watching opens with an explosion of action and thick-ear dialogue, I usually find myself stifling a yawn and hoping against hope that it will get a bit smarter. If it begins with a static close-up on the face of a character I’ve yet to get to know staring past the camera, to pick a random example, then you probably have my interest, at least for a while. Why? Because that’s not how movies traditionally begin and opening on such an image can’t help but serve as an announcement that the film in question is unlikely to play by the usual rules, and these are the films I tend to be drawn to these days. Of course, if that film then subsequently goes nowhere or disappears up its own backside, then that initial engagement is likely to sour. Even this tolerant viewer’s patience will only stretch so far.

Slovak filmmaker Martin Šulik’s second theatrical feature, Neha, a possibly ironic title that apparently translates as Tenderness, opens on a montage of almost static images of a young man – whom we later learn is 20 year-old Šimon (Geza Benkö) – lying, sitting and standing in a sparsely furnished and unkempt room. At this point we have no idea who or where he is or much about his state of mind, but my immediate supposition from his expression and body language was that he had been living in this room for some time and had lost interest in life and is now just lolling around in a state of dejection. Eventually he aleaves the room, wanders into the hallway outside and pauses to peer in through an open doorway. This will prove to be the film’s signature image, one that will be repeated many times in a variety of locations. We soon learn that Šimon is looking at his father, who is lying on a bed and staring blankly at the ceiling. Šimon then wanders into the kitchen, where his mother is reading. “What happened here?” he asks her, to which she coolly responds, “You beat up your father.” A short while later, he grabs a chair and wanders off to sit on his own in the woodlands out back. A short while after he is joined by his father. “What’s wrong with you?” he asks his son, who slowly lifts his feet off of a second chair to allow his father to sit.

Before we can discover whether the two actually converse, the film cuts to a wide shot of Šimon standing on a railway station platform with a bag in one hand. A short while later a train rolls in and Šimon boards it, seemingly the only passenger travelling from this quiet hamlet that day. In the next shot he is shown sitting on the floor of a different room to the one we first saw him in, dressed in his underclothes and flipping through a book on human anatomy, which inspires him to draw an outline of his hand on the wall. Eventually he tires of his studies and, seemingly on impulse, takes a pair of scissors and crudely crops his hair, then tentatively experiments with the idea of cutting his wrist, inflicting a small wound that he then hastily dresses before the blood flow becomes too serious. When we next see him he is dressed in a vest and shorts and running across a railway bridge, accompanied by the film’s disconcerting main theme, and the picture fades to black and stays that way just long enough to prompt expectations of an early final credit role. This motif will be repeated three times and is used to signal the end of one untitled chapter and the start of another.

On a first viewing, this introductory sequence is likely to provoke a number of questions. What prompted Šimon, for example, to assault his father and somehow erase it from his memory the next morning? When he boards the train is he leaving home in response or returning to college or university digs? When we see him browsing an anatomy book in an unfamiliar but unmistakably lived-in room, is he studying for a course he has been enrolled on for some time or has the timeline of the film jumped forward a few months? With that question in mind, is his hesitant experiment with wrist cutting prompted by a long period of estrangement from a family he now misses or a nihilistic response to the question asked of him by his father? Armed with the knowledge of what subsequently unfolds and a better feel for Šulik’s minimalist storytelling, things seem much clearer on a second viewing, and while some things are still left open to interpretation, it becomes clear that they not require further clarification within the frame of the story. We can see from what unfolds that Šimon is a troubled young man and that he has a (perhaps deliberately) confrontational relationship with his father, and all we really need to know about where he lives now is that he has separated himself from his immediate family. Whether he is on an official course of study or just curious about anatomy is ultimately irrelevant, but the number and subject range of books on his shelves and his interest in them is not, confirming as it does that Šimon is no mindless thug who just likes beating up on people.

The second chapter begins with Šimon in the washroom of an upmarket but almost empty restaurant, where he exchanges glances with an attractive older woman named Mária (Maria Pakulnis), who is dining with her boyfriend Viktor (György Cserhalmi). When Mária returns to her table, a minor altercation with Viktor prompts her to walk over and sit with Šimon instead, with whom she flirts and briefly dances before returning to her boyfriend. “Don’t do this to me ever again,” warns Viktor after painting his lips with Mária’s lipstick and kissing her hand and arm. Yet in the very next shot Viktor and Mária are driving home with an inexpressive Šimon sitting in the back seat.

After stopping off at what appears to be an unlocked private bowling alley for some more food and drink (I’ve certainly got questions about this place that will probably never be answered), they arrive back at Mária and Viktor’s apartment and sit down to watch some old home movies shot when Viktor and Mária were first dating. Simon divides his attention between the films and the unaware Mária, and when she gets up to pour Šimon a drink, he runs his hand up the back of her leg and under her dress. While she says nothing and doesn’t even look in his direction, her expression hovers somewhere between pleasure and extreme discomfort. When the film moves on to an embarrassing incident in which Viktor opened the door to a changing hut while Mária was topless, she furiously tries to prevent its screening but is physically prevented from doing so by a highly amused Viktor. When released from his grasp she responds to this ignominy by angrily switching off the projector and slapping Šimon hard enough around the face to make his nose bleed. Viktor responds by telling Mária that she should be ashamed of herself and demanding she apologise, which she refuses to do. Despite this blow-up, Viktor insists that Šimon stay the night, and before he beds down on the floor the far calmer Mária pays him a visit and, laying a friendly hand on his head, tells him not to be mad.

The unpredictability and uncertainty of purpose and even emotions of this scene lay the groundwork for much of what follows, as Šimon adopts they role of curious and tempted observer and repeatedly and silently watches Viktor and Mária through doorways and windows, gradually becoming an active participant in the life of a couple whose relationship has clearly fallen on difficult times. Audience viewpoints will likely vary here, but for all his charms as a character I quickly took a dislike to Viktor, whose game-playing with Mária all-too frequently descends into the sort of bullying that seems specific to men who get off exercising control over women. On a second viewing it seems clear that the seemingly inconsequential incident that prompted Mária to flirt with Šimon at the restaurant was not a one-off irritation but the latest in a long line of annoying behavioural tics on Viktor’s part, and barely a scene goes by without him undercutting his genuine affection for Mária with actions or words designed to hurt or humiliate her. Mária, meanwhile, seems caught between her love for Viktor and the pain that he seems willing to put her through on nothing more than a whim. Discomforting though this is sometimes to watch, it rings depressingly true and is something I’ve found myself witness to more than once in my own life. Viktor is in love with Mária but clearly suspects that their days as a couple may be numbered, and I initially suspected that his true feelings for her were repeatedly giving way to an underlying anger and desperation at the thought of losing her, which he selfishly takes out on Mária and occasionally Šimon. Coming back to the film after watching it through once I suspected that the roots of his behaviour lay in who he used to be before he met Mária, and that his bullying is more about exercising power and control over others than a genuine desire to inflict physical or emotional pain.

Šimon, meanwhile, quickly evolves from being a passive observer into a sounding board for the feelings and desires of both individuals, ultimately becoming Viktor’s co-conspirator and a symbol of temptation and self-realisation for Mária. And while his attraction to Mária may see him display the sort of tenderness towards her that was once and occasionally still is expressed by Viktor, Šimon is still morally weak enough to be goaded by Viktor into sleeping with Marta (Iva Bittová), a deaf single mother with whom Viktor has been having an affair. Intriguingly, on the few times Šimon does break away from the couple he’s quickly tracked down and brought back into the fold.

I have little doubt that there is enough meat for a sizeable essay on the nature of the three-way (and at one point, four-way) relationship that develops here, one whose emotional complexity and absence of easy answers is worthy of far more detailed examination than I’ve given it here (indeed, you’ll find just such a work in the booklet that accompanies this release). Any such literary breakdown would also need to address the film’s exploration of the nature of relationships in post-Communist Slovakia, an aspect of the film that, not being as well versed in the social politics of the country as I probably should be, I am not qualified to discuss with any authority. If you lived through the Velvet Revolution then I have little doubt that you would pick up on these elements more readily, but for those who did not the signifiers are also open to alternative readings. In the accompanying documentary, for example, Šimon’s behaviour towards this father is described as a symbolic “rejection of a generation of fathers,” but in cinema as in life, directionless teenage boys have been at war with their parents for decades. Perhaps the clearest pointer to the film’s socio-political subtext comes late in the shape of a home movie that provides a clear pointer to Viktor’s former occupation, one that would go some way to explaining – though not excusing – his more controlling and hurtful behaviour.

More than once I’ve seen the film compared to the work of Michelangelo Antonioni (Šulik himself cites Bresson and Tarkovsky as key influences), from the gradual disintegration of the relationship at its centre to Šimon’s lack of emotional expression and Šulik’s coolly observational approach and willingness to leave potentially important questions unanswered and open to audience speculation. But where the emotionally damaged characters in Antonioni’s La Notte found themselves in isolation amongst a throng of partygoers, the characters here seem to exist in a world that is almost devoid of other people. Yes, they spend much of the film inside their homes, and save for a restaurant waiter and a warden who reveals the origin of a church that Mária and Šimon visit, the places they go to all have an eerily abandoned feel. It’s a similar story when Šimon is away from the couple, running alone down deserted train tracks and the only person to board a train that feels almost like an unmanned and automated ride provided solely for his use. It struck me that this is not meant to be a portrait of how the world is but how it is perceived by the alienated Šimon and the self-absorbed Viktor and Mária, a sensation emphasised by the more discomfiting strains of Vladimir Godár’s unsettling score.

As Mária and Viktor, experienced actors Maria Pakulnis and György Cserhalmi are both quietly excellent, getting completely under the skin of their characters and making me feel for (and occasionally get frustrated by) Mária and be fascinated by Viktor even as I feared what he might do next to re-assert his authority. They are effectively counterpointed by newcomer Geza Benkö’s considerably more muted performance as Šimon, who is initially presented as an emotional blank slate, a featureless ball of clay whose potential to be shaped by his involvement with Mária and Viktor is hampered by his disconnection from the world around him and his seeming inability to engage with anyone or anything on any more than a superficial level. Perhaps tellingly, the one time he drops this shield and seems to really connect with another person is when playing with Marta’s small child – when able to spend a little quality time with someone who has no power to manipulate him, he opens up and seems genuinely happy.

When I first watched Tenderness I was unsure quite how I felt about it right up to its ambiguous but oddly hopeful ending, despite it having held my attention unwaveringly throughout. If you’re well versed in Slovak socio-political history then you may well be more tuned to this aspect than of the film than I was on my first viewing, but if not then it still compels as a coolly observational study of troubled (and troubling) personal and familial relationships in a state of potentially self-destructive transition. Armed with a little more understanding of the filmmakers’ intent, the time and place in which it is set and the knowledge of how the story unfolds, a second viewing proved more rewarding than the first, and a film that I was initially intrigued by developed into one that genuinely gripped and fascinated me. It is, in its quiet and carefully constructed way, one hell of first feature, and has done me the inestimable favour of tuning me in to a director whose work I was previously unfamiliar with but now feel compelled to track down and see in its entirety.

A clean and crisply detailed 1080p transfer in the film’s original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, sourced from a new 2K restoration approved by director Martin Šulik. The image has been graded to give cinematographer Martin Štrba’s naturalistic lighting a warm, earthy feel that shuns bright prime colours and at times has an almost period look to it. Elsewhere, particularly on exterior footage, the colour is bery naturalistic. The contrast is very nicely balanced, and while the black levels are generally sound they do occasionally soften a tad in line with the interior colour grading. Any dust and dirt has been cleaned up and a fine film grain is visible.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is clean and clear, with no background hiss or fluff (each scene has background ‘atmos’ sound that can occasionally sound like errant noise but definitely isn’t), particularly important for a film the often lets is visuals do the talking. Vladimir Godár’s sometimes troubling score is most effectively rendered here.

Optional English subtitles kick in automatically but can be switched off if you’re fluent in Slovak.

On Tenderness (26:13)

A new documentary produced by the Slovak Film Institute that looks back at what proved to be a key film for many of those involved in its making, built around interviews with screenwriter Ondrej Šulaj, composer Vladimir Godár, cinematographer Martin Štrba, ‘dramaturgist’ Zuzana Gindl-Tatárová and director Martin Šulik. The genesis and writing of Tenderness are covered, and Šulaj reveals that the decision to focus on a small number of characters was driven in part by budget restrictions. Sorry, but I stand by my original reading on this. All discuss how the changing times they were living through at the time of the film’s production is reflected in the film’s socio-political subtext, and Šulik suggests that he and his collaborators were still learning their craft whilst making the film. All hold the film itself in high regard and Godár admits to liking it more now than he did when it was made and that he feels it gets better with every viewing. I do get where he’s coming from on that score. Šulik also talks about his influences, from author Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha to the films of Robert Bresson and Andrei Tarkovsky, and intriguingly regrets his refusal to include any humour, “because humour makes films more human.”

Hurá (1989) (27:55)

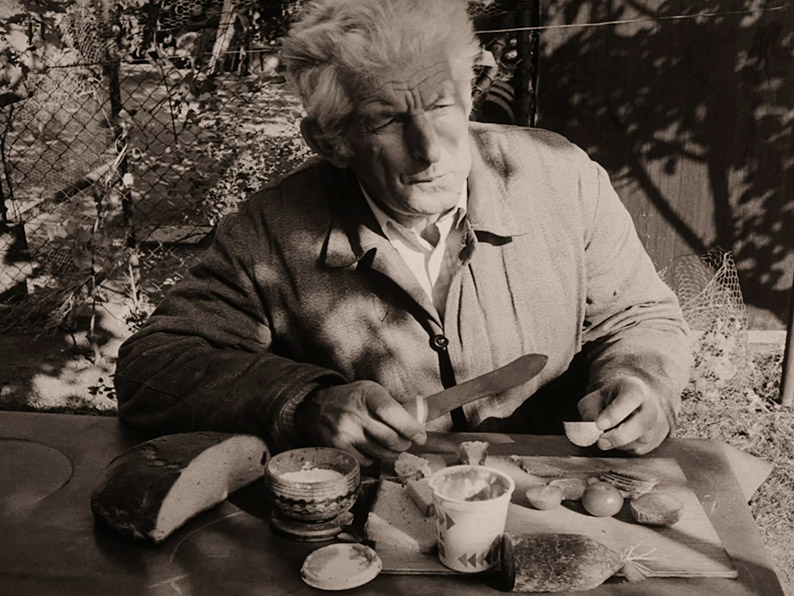

A half-hour documentary directed by Martin Šulik and photographed by Martin Štrba a year before they collaborated on Tenderness in which a middle-aged man named Alojza Paldana looks back at his life in Communist-controlled Slovakia. Based around an audio interview with Paldana and coupled with propagandist newsreels and footage of Paldana tending his garden and revisiting a key location from his past, it tells a fascinating, revealing and sometimes deeply troubling story of a man who, despite playing by the rules of a restrictive society, ended up in prison for what sounds like nothing more than befriending a couple of Japanese men in a bar. Even his willingness to sign up to work as a uranium miner as a young man came back to bite him later when he and his comrades learned just how damaging the material they were handling could be. Yet for all this he remains impressively philosophical, arguing that if you can stay healthy enough to enjoy the company of your children for a bit longer, then all bad things can be forgotten. By the way, Hurá is apparently Slovak for "Hoorah!" and the film appears to have also undergone a restoration and looks terrific here.

The accompanying Bookletis almost solely dedicated to a detailed essay on the film and the director by respected film writer Peter Hames, who in the examines the film on an almost scene-by-scene basis, before moving on to director Šulik’s subsequent film career, his involvement in Czech film and his regular collaborators. If you’re new to this filmmaker or Slovak cinema in general, this is especially useful reading.

The Blu-ray release of Tenderness is the sort of title that reminds me how lucky we are that a label like Second Run exists. It’s film I might never have otherwise seen, and having watched it twice now (and made time to do so again this weekend) I’m genuinely glad I had the opportunity to do so. It’s become a critical cliché to point out that it won’t be for everyone, but while a little bit of knowledge of Slovakia’s socio-political history might go a long way here, even if you know next to nothing about it the drama still compels and the emotional touchstones feel unsettlingly familiar. Once again, the presentation is first-rate, and the inclusion of the retrospective documentary, the Šulik short film and the Peter Hames essay really added to my appreciation of this confident and impressive first feature. Definitely recommended.

|