| |

"Women are called birds because they pick up worms." |

| |

A personal favourite feminist badge from the 1970s |

More than once I've discussed my fondness for Oliver Reed as a performer, but I've never really touched on the contradiction that separates his image from his on-screen persona. Reed's reputation as a hard-drinking, womanising macho wild man was notorious and well-earned. More than once I watched him interviewed when he was just a little drunk and have strong memories of a late-night round-table discussion where he was absolutely plastered. He'd do almost anything to get a reaction, and some of the things he got up to with his close friend Keith Moon became the stuff of showbiz legend. Yet despite his imposing physical presence and menacing stare, his voice had an almost aristocratic ring, evident in his precise and regional accent-free delivery and his tendency to speak in a thoughtful throaty whispers. This contradiction could, on occasion, make the characters he played feel a little like cultured yobs, but more intriguingly it also makes it hard to pinpoint their backgrounds. Is he a working-class brawler made good who has adopted a middle-class mode of speech to move more easily in professional circles (my late father, an East London-born salesman, could switch that on and off in a heartbeat), or the son of landed gentry who has rejected his upbringing to get down and dirty with people he can more readily relate to?

In the 1964 The System, an important stepping stone on the then young Reed's road to future success, he plays Tinker, the leader of a gang of morally suspect lads who seduce and then abandon young female holidaymakers, whom they refer to 'birds' and 'finches' and whom Tinker targets through his job as a beach photographer in the Devon seaside town of Roxam (actually Torquay). They even board Roxam-bound trains at an earlier station to walk its corridors to locate potential prey before they reach their holiday destination.

Now I have to admit that I'm not old enough to have any memories of commercial seaside photographers, and they must seem like a peculiar concept to a new generation of young people that have high quality cameras in their pockets at all times. How beach photographers made a living was by taking candid pictures of holidaymakers, most of whom did not own their own cameras, often catching them off-guard as they walked or stood admiring the view. The subjects were then approached and handed a docket telling them where they could buy a copy of the photo as a holiday souvenir. While this particular strand of the photographic profession may have long since abandoned the beaches, it still survives at theme park rides and at venues where you'll have the chance to don a costume or pose at a location where the use of tourist cameras is slyly forbidden. Earlier this year I visited a commercial spa hotel in Osaka, and my companion and I, dressed in yukatas with bamboo parasols in hand, were cheerily posed on plastic recreation of a traditional Japanese wooden bridge for a photo we were then encouraged to buy an instantly produced print of. We politely declined, but the sheer number of people that the two-person team was busy photographing each day (more than once there was a sizeable queue of eager subjects) made it clear that in the right location this is still a rather lucrative business.*

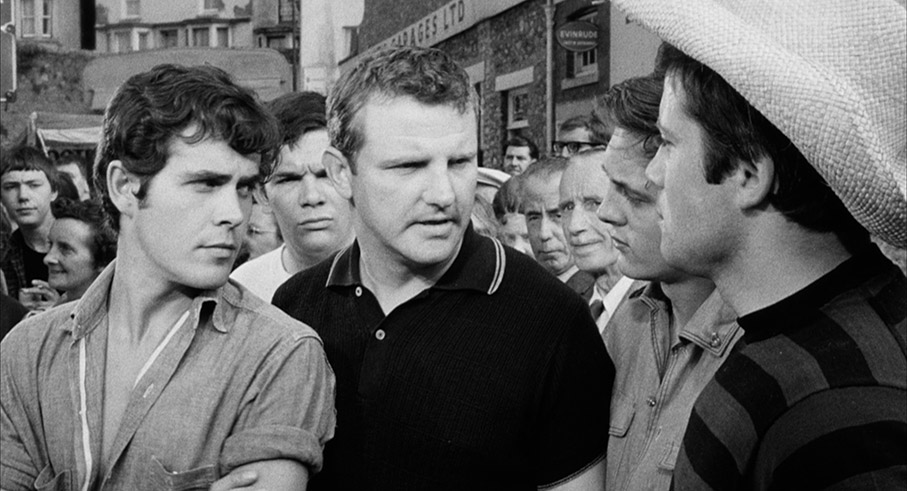

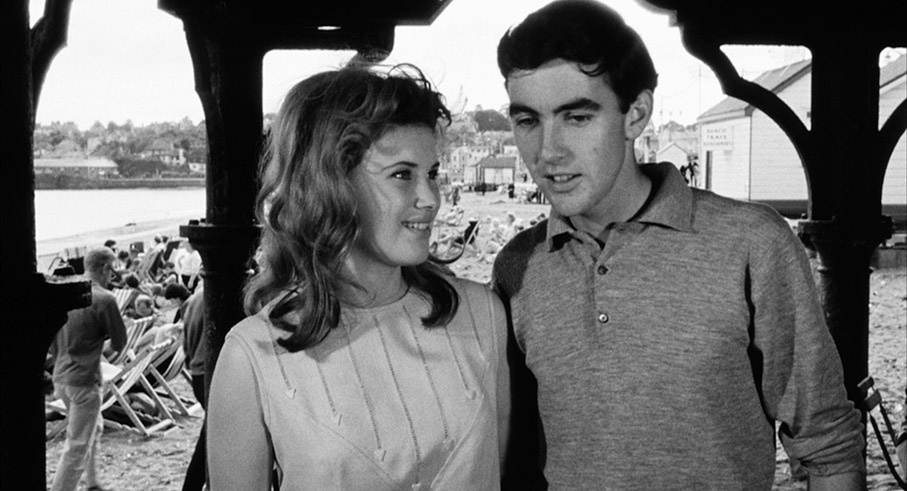

In The System, Tinker is a legitimate seaside photographer who works for a small but busy photographic company run by the older Larsey (Harry Andrews), but who uses the trappings of his profession to procure the names and guest house addresses of the girls he smilingly targets. He then shares this information with members of his gang of mod-dressed young men, which they use to approach young female holidaymakers, whom they romance on the cheap, then sleep with and discard in order to move on to the next one. This, it turns out, is The System of the title. As the film gets under way, newcomer David (a young and innocent-looking David Hemmings) is briefly introduced to Tinker by his cousin and seems initially uneasy at the behaviour of his new companions. As they boisterously but harmlessly harass attractive and well-to-do new arrival Nicola (Jane Merrow), to whom the self-confident Tinker has already taken a shine, David's initial air of discomfort at the group's shenanigans was one I found easy to empathise with. This apprehension soon gives way to curiosity, however, as David is schooled in the purpose and methods of The System in a sequence that doesn't blatantly play as the exposition it most definitely is. Surprisingly, the initially quiet David takes to The System like a proverbial duck to water, and by the end is showing signs that he might soon usurp Tinker as its leader.

The System is a less well-remembered example of British New Wave cinema of the late 1950s and early 60s, a movement whose most famous works are now widely acknowledged as British film classics. Quite why The System rarely even gets a mention when these films are discussed is a matter for conjecture, though I do have a couple of theories about this. The first is that it was directed by Michael Winner. Yep, that Michael Winner, the man behind the Death Wish films who became better known in later life as a champion of law and order and conservative politics (I wonder what he'd have made of the current shit-shower and their complete contempt for the rule of law), and for his role in condescending TV commercials, where he advised women panicking about car insurance to "calm down, dear." He was also, I should point out, a vocal supporter of gay rights, and once famously laid into tit extraordinaire Richard Littlejohn on air when the dreadful man was verbally attacking two lesbian guests he'd clearly asked on the show to belittle in this manner. What is not widely known (and this was certainly new to me) was that at one point Winner was the youngest working director in the British film industry. If you want to get that into perspective, he was just 29 when he directed The System and by that point had already helmed 7 features and a number of short films, one of which has been included on this disc. Yet so famous (or infamous) did he become for his later work and activities that his early and frankly far more interesting British films sometimes get unfairly overlooked as a result.

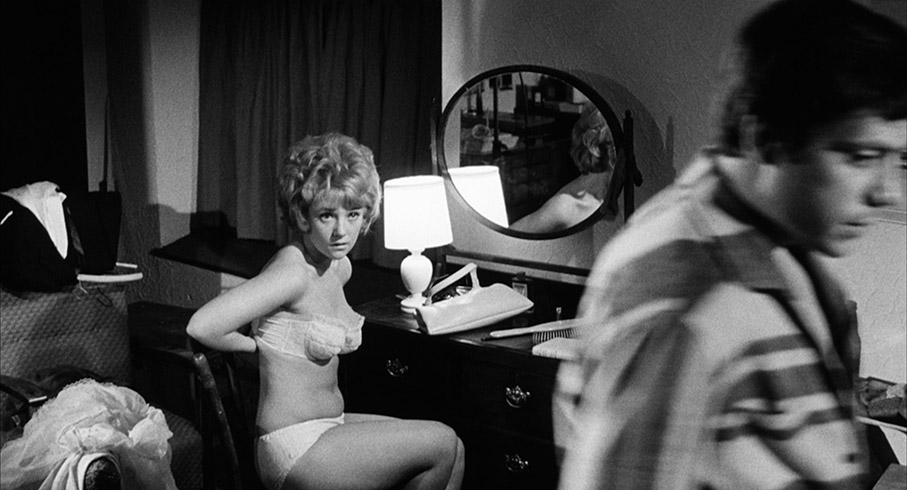

But there's more. While the film's setting certainly differs from other British New Wave works of the era, many of the topics it addresses had already been confronted by the likes of Jack Clayton's Room at the Top (1959), Karel Reisz's Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Tony Richardson's A Taste of Honey (1961) and John Schlesinger's A Kind of Loving (1962). These films were trailblazers for the British New Wave, and by the time we get to The System, many of the ground that had been broken by the New Wave films no longer had the shock of the new. As an example, consider group member Nidge (John Alderton), who reveals to Tinker that one of the girls he has slept with is pregnant. Tinker responds by giving him a phone number to call, and we don't need verbal confirmation to know the number in question is that of an abortionist. Crucially, it's something a contemporary audience would also have been able to deduce precisely because the subject of unwanted pregnancies and abortion had already been broached by the film's cinematic forebears. Herein, of course, lies the difficulty when talking about older films that pushed now broken boundaries, particularly if you didn't live through the period in question. Yet as noted in the extras, the film's subject matter was still considered touchy territory in 1963, landing the film an 'X' certificate after famed producer Michael Balcon and outgoing BBFC director John Trevelyan went to bat for it against strong objections from incoming BBFC chief Herbert Morrison, who wanted it banned. And in some respects the film was definitely (and in some ways, unknowingly) ahead of the curve, prefiguring the concept of the male sexual predator as likeable charmer that was central to Alfie (1966), while Tinker and his suit-dressed companions would not look out of place in the 1979 Quadrophenia, key sequences of which were also set in a seaside holiday resort. It must also be one of the first British films in which a woman appears topless, which despite lasting only a few frames and being captured in discreet and frankly non-exploitative wide shot, apparently really got Morrison's back up.

What's interesting about The System in relation to the films that prefigured and paved the way for it is that it repeatedly plays to expectations that it then undermines. Thus from almost the moment that Nicola inadvertently catches Tinker's eye you just know they're going to end up together and that she's going to have a transformative effect on him, but the specifics of how this unfolds are peppered with quiet surprises. For a while it even seems possible that they won't sleep together and that the relationship will develop along different lines. Yet after they do it's Nicola who proves to be better equipped to move on from a holiday romance that has become more important to Tinker than he would like to admit. This tinkering with expectations also applies to Nidge, who opts not to take Tinker's advice and to keep the baby, and it's thus only a matter of time before he's planning a wedding, a not unusual decision at a time when children born outside of a union that has church or state approval were cruelly stigmatised as 'illegitimate'. Yet having hesitantly accepted Nidge's request to perform the duties of Best Man at the wedding, Tinker's reception speech is awkwardly brief and cheerlessly dismissive of the whole concept of marriage, while the surreal procession at the night-time beach party that follows would not have looked out of place in The Wicker Man. And having established that The System as a very male activity, one that includes territorially-driven physical battles with a rival souvenir photographer and his gang, the film throws a small curve ball in the shape of Suzy (Barbara Ferris), a former girlfriend of Tinker's who is now operating a one-woman System of her own. There's also a strong suggestion that many of the targeted young women have come to Roxam looking for the very holiday affairs that The System has been set up to provide, which casts its purveyors more as gigolos than exploitative predators.

That a class difference that separates Tinker and Nicola is repeatedly hinted at in their early encounters and then more firmly established when Tinker is invited to Nicola's father's plush holiday home, where Reed the actor has to effect a comical upper-class accent to take the piss out of young men whose vocal delivery is not that much posher than his. His mocking of them sees him drawn into a tennis match that his rich and sporty opponent Ivor (Jeremy Burnham) seems destined to win from the off, humiliating Tinker in front of Nicola and a couple of Ivor's insufferable upper-class-twit friends (one of whom is played by future TV star Derek Nimmo). Intriguingly, this fails to make even a small dent on Tinker's ego, who shrugs off the defeat with a resolute smile and says to Nicola philosophically, "you know, you people are unbeatable – you always win on your level and I always win on mine."

The script, by Paul Draper, who went on to work mainly in television, is a lot smarter than a casual first viewing might suggest, and save for the 'you're watching a movie' tic of using push-wipe transitions – done, I'm guessing to emulate a film being wound on to the next shot in Tinker's camera (it doesn't really come off and sits uneasily with the film's otherwise more naturalistic style) – Winner's direction is controlled, low-key and effective. You can take how you please the claim made by actor John Porter-Davison in the special features that Winner was constantly calling on the advice of his cinematographer over where put the camera, although the fact that the cinematographer in question was Nicolas Roeg can't help but make you wonder if there wasn't at least a grain of truth in this. Here the look that Roeg brings to the film is as far from his vibrant and stylised colour work of the same year for Roger Corman's The Masque of the Red Death as you could imagine, his high-contrast monochrome imagery grounding every scene in tangible reality and walking a precise line with his night-time work especially, creating visually captivating images that never feel lit and framed to look that way.

Whatever your view on the film's look, Winner certainly deserves credit for its brisk but never overly hurried pacing and for drawing fine performances from a universally strong cast. Having just completed a short run of films for Hammer, Oliver Reed gets what may be his first chance here to really show what he can do, and he responds with aplomb. Don't get me wrong, I enjoyed the hell out of Curse of the Werewolf, but it's as Tinker that Reed really comes into his own, demonstrating a range, control and knack for nuance that makes it all the more mysterious that he had to wait another five years before Ken Russell's Women in Love really propelled him towards stardom. He's well matched by young Jane Merrow as Nicola, who exudes a sense of cool control from the moment we first see her and convinces completely as someone who could turn The System on its head.

I'll admit that it took me a couple of viewings to really warm to The System, but warm to it I definitely did. Reed is certainly a key attraction and he's at his best here, nicely underplaying (we'll give a pass for his comically gurn-peppered dancing) and getting under the skin of a role he might technically be slightly too old for but to which he seems suited nonetheless. But he gets strong support from a well-chosen and well-directed cast, who respond enthusiastically to Draper's thoughtful screenplay and have an interpersonal chemistry that really sells the various relationships as plausibly real. There's also a sometimes lively 60s soundtrack to savour, one that includes tracks by The Searchers, The Rocking Berries and The Marauders. It's a neat rediscovery from Indicator that apparently wasn't as big a hit as anticipated on its UK release, but did some serious business in America under the horribly clunky re-title, The Girl-Getters.

A solid 1080p 1.85:1 transfer of a film whose gritty, high-contrast monochrome cinematography must have presented a few challenges to the good people responsible for the restoration and transfer. Detail is crisply rendered, if not razor-sharp, but this is very much in tune with the film's chosen aesthetic, as are the coalhole black levels that swamp darker areas and some exposure-driven burnt-out white highlights. Grain is evident throughout and adds to the almost reportage feel, though is more visible in some scenes than others. There are no signs of any former damage or wear, and I didn't see any dust spots.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is generally clear, though some of the background location sound lacks finesse. The music sounds good and the dialogue is distinct, and there is no underlying crackle or damage to contend with.

Option English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Audio commentary with Thirza Wakefield and Melanie Williams

OK, here's the thing. More than once we've been prompted to point out that sometimes we'll write a review of a film, only to have some of the points we have made echoed so precisely in the special features that it makes it seem as if we've cribbed directedly from them. It is perhaps inevitable that when you're struck by an aspect of a work you've only just seen for the first time, those who've made a study of the film in question will have long ago done likewise and possibly even written a detailed paper on it. But just occasionally coincidence plays an infuriating role. Prior to The System, I have reviewed (or in one case co-reviewed) four films for this site in which Oliver Reed stars, and each time have had something new to say about the actor, including a personal story involving a close friend who has since passed away. In my pondering on how to get this review rolling, I realised that I'd not yet talked about the conflict between his image and his diction, and immediately set to work. Happy enough with my opening paragraph, I moved on to review proper, only moving on to the special features later (we do tend to do this, in part to avoid being influenced by the opinion of others). I started with this commentary, and to my absolute disbelief, 30 minutes in film historians Thirza Wakefield and Melanie Williams chose to talk about that very same thing using language so similar to my own that I'd swear they were using my review as notes had they not recorded this commentary before I even laid eyes on the film. After banging my head against a table top for ten minutes, I genuinely considered deleting my opening paragraph, but ultimately decided to include it and go on the "can you believe it?" rant above.

Anyway, I'm guessing that a good part of the reason that Wakefield and Williams talk about this here is that they cover just about everything to do with the film in what proves to be an impressively researched and engrossingly analytical commentary. They pick up on the film's links to other works of the period and how it looks forward to films to come (they even draw parallels between Tinker and Father Grandier in The Devils), as well as discussing the female characters, other British seaside-set films, the script, the cinematography, the locations and a lot more. A fine commentary, but dammit…

Jane Merrow: Getting the Girl (17:52)

Actor Jane Merrow, who plays Nicola in The System, recalls her early theatre work, landing a role that Michael Winner wanted Julie Christie for, Oliver Reed's evening drinking parties and the on-screen chemistry she had with him, the nude bathing sequence, the "wonderful" script, and more. She gives a passing mention to the fact that she and David Hemmings ended up as a couple, suggests Winner was a better producer than a director (he apparently really knew how to market a film) and says of Nicolas Roeg that he loved everything about film. Colour us unsurprised at that one.

John Porter-Davison: Drinking and Dancing (5:39)

Actor John Porter-Davison, who plays group member Grib, kicks off by assuring us that most of the actors working on film were permanently pissed and suggests that the younger generation do not realise just how much he and his contemporaries used to drink back then. I'm a little younger than him, but I can still heartily second that – frankly, I'm amazed I made it through my college years alive. He describes Oliver Reed as "the ringleader," recalls that the rest of the (young male) cast looked up to him, and remembers a drinking game that ended with Reed and fellow actor Iain Gregory tossing him into the sea from a worrying height whilst he was horribly drunk. He describes Nicolas Roeg as the best lighting cameraman he ever worked with, and suggests that it was he that made the film good, as Winner was always asking him what to do.

Jeremy Burnham: Fun and Games (3:50)

Actor Jeremy Burnham, who plays Ivor in the film but doesn't get an on-screen credit, recalls getting the role in part because he was good at tennis, what happened when Derek Nimmo was pulled over for speeding, and Oliver Reed stepping in when some local boys challenged actor Andrew Ray (who plays group member Willy) to a fight. Oddly, they weren't as keen to take Reed on.

Image Gallery

19 promotional stills and 3 posters, the most interesting of which looks to be Polish, as ever.

Haunted Britain (23:31)

An early work from director Michael Winner that has the look of one of those short films that used to play in support to main features back when the whole concept of double-bills was starting to fade. As a historical curio, it's a valuable inclusion and is in surprisingly good condition, but as a work of film entertainment I found it a slog. Introduced and narrated by David Jacobs (a name that will mean nothing to a younger audience), it's hard to tell whether the film is taking its subject seriously or is flat-out taking the piss, and I wasn't sold on either interpretation, despite the odd moment of invention on Winner's part. It includes low-budget costumed recreations of uninteresting historical events (why is it that ghosts seem largely confined to the aristocracy?) and a man who looks more like a well-fed banker than the clairvoyant he claims to be. Research suggests he was the real deal, which only makes him seem more preposterous. And yes, there's a 'jokey' ending. Oh, how I laughed.

Booklet

Following the film credits, author and critic Andy Miller makes a solid case for why The System is Winner's best British film, after which there is an extract from Winner's 2004 memoir, Winner Takes All: A Life of Sorts, in which he looks back at the film's making. Up next are extracts from three contemporary critical reviews, none of which are exactly raving. The credits for Haunted England have also been supplied, and there's an enthusiastic shout for its apparent qualities from film archivist, writer and historian, Vic Pratt. I remain unpersuaded. As ever, it's all illustrated with film stills and poster artwork.

If, as I have to admit I initially did, you balk a bit at the notion of watching a Michael Winner film, then it's worth putting that prejudice on hold for The System, an unfairly forgotten (well, not by everyone, obviously) late entry into the British New Wave cycle of films from the early 60s. It's smarter than it's pop song opening titles lead you to believe it will be and boasts an excellent cast and some captivating sequences consisting of little more than two characters in conversation. It also has the strangest wedding celebration I've ever witnessed. Another fine release from Indicator, which as ever looks great and has a strong collection of special features. Recommended.

|