|

As I may just have mentioned just a few times before on this site, I have something of a passion for Japan and its culture. It's a country I love (but can only intermittently afford) to visit, and when there I tend to completely immerse myself in the locale and all it has to offer, not always easy for someone who stands a couple of inches taller than the doorways in many of the hotels. I have a particular fondness for local cuisine, whether it be the easy availability of top quality sushi, tempura and udon dishes, or the liquid delight that is shôchû, my absolute favourite alcoholic tipple and one that while widely available in Japan, is almost impossible to track down in the UK. But despite having a sweet tooth that may one day land me in the emergency room, one food that that I have never really warmed to is the Japanese take on confectionery, notably those deserts and sweet treats made from red or (especially) black beans.

One such delectable snack, known locally as dorayaki, consists of a sweet bean paste sandwiched between two small American-style pancakes. I wanted to like it, I really did, but after slowly munching my way through two (on separate occasions), I decided that this particular food just wasn't to my taste. After watching Kawase Naomi's captivating An [Sweet Bean], I'm starting to wonder if maybe the bean paste that was the source of my culinary displeasure simply wasn't up to scratch. If the film is to be believed, creating the very best sweet bean paste is not a culinary task but an art that requires the sort of intuitive skilsl employed by master brewers of the very finest sake.

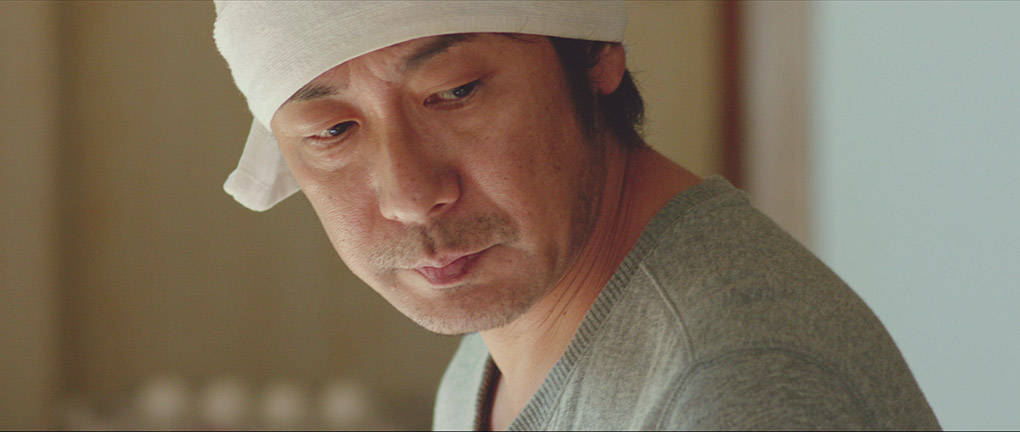

The film begins in the springtime in a suburb of an unspecified city, as Sentarô, the manager of a small dorayaki shop, wakes and shuffles somewhat glumly to work. As he goes about his duties, cooking pancakes and serving customers, we get the impression that the business is ticking over but not exactly thriving. Certainly the only customers that we initially see are three giggling schoolgirls – who seem to enjoy trying to get a rise out of Sentarô – and their more subdued classmate Wakana, whom Sentarô has befriended and to whom he gives his rejected pancakes to take home to her financially strapped mother. Sentarô has nonetheless advertised for part-time help, which attracts the attention of Tokue, a cheerfully eccentric, 76-year-old woman with a hand deformity who claims to have always wanted to work at such an establishment. Despite her enthusiasm, Sentarô believes that the work would prove too demanding for a woman of her age and physical condition, and politely lets her down, even after she offers to work for substantially less than the going rate. The upbeat Tokue is not so easily dissuaded, and later returns with a carton of sweet bean paste – the 'An' of the title – that she has made herself, which she leaves with the initially dismissive Sentarô. The paste turns out to be the best he has ever tasted and he thus agrees to take Tokue on, but only if she makes the same paste for him every day. Little does he realise the time and care required to make just a single batch, but once he starts using it in his dorayaki, word gets around and business is soon booming. A strong bond between the two begins to develop, but their friendship and working relationship is soon put in jeopardy by the misinformed prejudices of the shop's brusque female owner.

Now my problem here is the familiar one of how much to reveal about what follows, and specifically the nature of the above-mentioned prejudice. The thing is, it would be nigh-on impossible to discuss what most affected me about later events without revealing a key piece of information about Tokue, which some may well twig from an early stage but a good many others will not. Out of curiosity, I did a quick scan of other reviews to see if they were being as guarded as me, and to my considerable surprise, Sight & Sound gave away the very thing I'm so carefully dancing around in the brief sub-header that fronts their review, and it seemed to crop up in almost every other review that I checked. This does suggest that if you plan to read up on the film before giving it a look, then you're unlikely to be able to avoid this little nugget of information. So here's the deal – if you want to go in as uninformed as possible, then I'd skip to the final paragraph of this review, and do it without even a glance at what immediately follows, as I'm about to reveal what just about everyone else has already discussed and throw in a couple more spoilers of my own.

What rattles the owner of the shop about Tokue is the deformity in her hands, which she believes is evidence of leprosy (more widely known now as Hansen's Disease), and despite the positive effect her culinary skills are having on the business, that's not someone the owner wants working in her shop. Traditionally, this would be revealed over time to be a case of prejudice based on misinformation and rash a misreading of symptoms, but here it is quickly confirmed to be the truth by Tokue's address, which the owner recognises as a home for those afflicted by Hansen's Disease.

The following day, the depressed and hungover Sentarô bunks off from work, leaving the shop closed and Tokue to make up the bean paste for the following day. But when eager customers start tapping on the window, Tokue opens up and serves them anyway. When Sentarô arrives the following morning and discovers what has happened, instead of politely dismissing Tokue as the owner has ordered, he asks her to stay on and help serve the customers, a symbolic promotion that delights the older woman. Only when rumour (which we never hear) keeps the customers away does Tokue herself elect to take her leave, her end-of-day departure so loaded with finality that it triggered the first of several large lumps in my throat.

It's in the scenes that follow that the film takes its most delicate steps, teetering on the edge of sentimentality but actually radiant in its humanism (and beware, there are some spoilers ahead). By this point both Sentarô and Wakana have been deeply touched by Tokue's dreamy optimism, and elect to visit her at the home in which she resides. Wakana has done some reading by then on Hansen's disease and prepares Sentarô for what they may encounter, people missing their fingers, limbs or even their noses. And shortly after they enter the grounds of the home that's exactly what they see, but the small gathering of residents that they and we encounter are shown cheerfully interacting in the warm light of the garden in a manner that prompts you to see them as people before even becoming aware of their afflictions. It consists of just three brief shots, but they beautifully undermine a still widely held fear of a disease that we now know can be quickly rendered non-contagious by treatment. This challenging of prejudice is taken a step further when Sentarô and Wakana meet up with Tokue and her friend Yoshiko, who present them with food that Tokue has prepared, which after a moment's cautionary hesitation on Sentarô's part they both eat and enjoy, an almost unconscious rejection of the fears of the shop's more judgemental customers.

It's here that the film hits emotional pay dirt, as the older-looking and visibly weaker Tokue reflects on her childhood and quietly delights in Sentarô's enjoyment of her food, but with a tiredness that signals that the almost child-like optimism and happiness of her time at the shop are now gone forever. It really is hard to convey the emotional impact of this gentle and cinematically unfussy scene, as so much of why it works as well as it does is down to Kiki Kirin's utterly superb performance as Tokue – so beautifully nuanced and utterly, believably real is she here that I found myself almost continually wiping away tears as I realised where the story was likely to take us next. And yes, Kawase pushes a number of emotional buttons here and in the scenes that follow, but there's not a note of music used to enforce or exaggerate its effect – the power of these scenes comes solely from the performances, the imagery, and Kawase's confident but feather-light handling.

Nature is very much a character in this film, one whose beauty is celebrated but also seen as integral to human existence and the pleasures of life – it's no chance thing that the key trigger for change and development in this story is a sweet paste made from plants and lovingly farmed and crafted by humans into a new form. Even the visually stunning early shots of backlit cherry blossom that surround Sentarô's shop are in no way purely decorative (and rarely have I seen the overwhelming beauty of the cherry blossom season at its peak captured on film as sublimely as it is here), providing as they do a framework for a drama that is intrinsically linked to the cycle of life. The blossom also provides a thematic conclusion to a film that gives us only tantalising hints of what lays ahead for Sentarô and Wakana, allowing room for speculation on exactly how Tokue's time in their company has affected them and how this will later shape the course of their lives.

I have absolutely no doubt that some will claim that An has been primarily crafted to prompt an emotional response in the manner of a low-key, sentimental weepie. Certainly its storyline is free of serious complication or startling twists, and the course that it takes in the later stages is not hard to predict. But Kawase's seemingly effortless way with observational realism and her focus on character, coupled with a string of winningly naturalistic performances and an evocative use of light, framing and location sound, make for disarmingly seductive viewing. The result is a film whose considerable emotional impact stems largely from the fact that we care so deeply about these people, despite knowing precious little about them until surprisingly late in the proceedings. It's also a work whose plea for understanding and tolerance may be delivered in a whisper, but still resonates throughout the film and stays with you long after the credits have rolled.

Some sources suggest An was shot on 35mm film, but the occasional burned-out highlight and variable contrast sometimes have more digital feel. Wonderfully balanced with solid black levels on sunlit scenes, the contrast softens somewhat in darker sequences. I'm guessing this was a deliberate decision made at the grading stage, one quite possibly down to director Kawase's fondness for naturalism in all aspects of the production – none of the scenes here look artificially lit and may well have been captured in largely natural light. For the most, part, however, this feels just right, and the opening vistas of sunlit cherry blossom genuinely took my breath away. Given that this 2.35:1 transfer was likely made from the HD digital master of the final edit, the image is spotless, the detail crisp and the colour most attractively rendered.

You can choose between Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround soundtracks, both in the original Japanese (no English dubs here). Both are clearly mixed with an excellent dynamic range, but the 5.1 is more subtly inclusive, having a richer feel, spreading location ambient sound around the room and delivering pristine reproduction of David Hadjadj's score.

The optional English subtitles are clear and unobtrusive.

Listen to Azuki's Voice: An Interview with Kawase Naomi (35:28)

A busy interview with director Kawase Naomi, who frequently provides some unexpected answers to textually presented questions (asked if she is influenced by other Japanese filmmakers, her answer is effectively "No"), but her responses are always detailed and interesting. She gives her reasons for using non-professional actors, has positive things to say about the Cannes Film Festival (where she was a jury member last year), cannot understand the appeal of working in a big city like Tokyo, and reveals that things have improved for female directors in Japan during the past five years. She does, however, suggest that while technical skills and access to equipment is improving, the ability to embody the inner world is in decline. There's a lot more here, all of it good.

Trailer (1:42)

A fascinating and smartly assembled sell that avoids revealing what I danced around by focussing only on the film's first half, out of which it fashions a seemingly complete, feel-good story.

Also included in the release version is a 32-page booklet featuring a new essay on the film by critic Philip Kemp, an interview and statement from Kawase, and production images, but this was not supplied for review.

I was actually surprised to discover that An was adapted from a novel (by Sukegawa Durian, who apparently had Kiki Kirin in mind as Tokue when he wrote it), given the simplicity of its story and the unobtrusively observational nature of its telling. It may not work for all, but I'm far from the first to be utterly entranced by this film and its characters, and have little doubt that it will continue to find an appreciative audience on Blu-ray and DVD. A strong transfer is backed by a solid interview with director Kawase Naomi and what is very likely a decent booklet (they usually are). For the film, the transfer and that key extra feature, this fine release is warmly recommended.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|