|

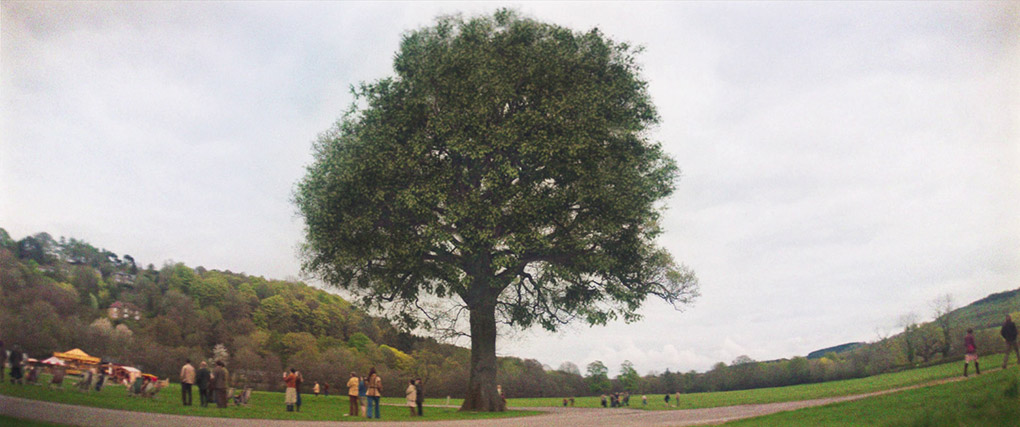

Yorkshire, somewhen in the 1970s. Richard (Matt Smith) and Juliette (Morfydd Clark) live in a remote house called Starve Acre with their young son Owen (Arthur Shaw). However, their life is disrupted when Owen starts behaving in a disturbing manner. After tragedy strikes, Juliette seeks solace in the local community while Richard busies himself with investigating local folklore, in particular a large oak tree where strange powers are centred.

Starve Acre, written and directed by Daniel Kokotajlo from the novel by Andrew Michael Hurley, is an effective latterday entry in the thriving subgenre of folk horror. While this subgenre can be found in cinema and literature all over the world, its loci classici are three British films from the late 1960s and early 1970s: Witchfinder General (1968), Blood on Satan's Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973). While these films are different in many ways, in setting (England or Scotland, historical or contemporary), and whether they include supernatural elements or not (one of the three does), they do share an emphasis on the rural parts of Britain and local folklore and customs. Starve Acre follows this tradition, with the threat rooted in stories of the past. In this case, supernatural events do occur. There are some spoilers ahead, though they are of events which have already occurred when the novel starts and which happen around twenty minutes into the film.

There's a timeless feel to the film. While it's set in period, it's not specified as to exactly when as we aren't given too many signifiers, hardly any in fact. Going along with the period setting is the usual restriction (or liberation) of having no Internet, social media or smartphones, so enabling the characters to be isolated more than they might be nowadays. The period is a little fluid. At one point, Juliette and Harrie are watching the BBC production Hamlet at Elsinore on the television, with Donald Sutherland getting a closeup as Fortinbras, which was broadcast on 19 April 1964 and not again until 2023, so how they're watching it is unknown. The two women have a conversation about the relative sexiness of Michael Caine and Gene Hackman, which would suggest the 1970s, as does Richard listening to Jethro Tull's "Living in the Past", released in 1969, on his car radio. Richard's Doctor Who reference (see below regarding the subtitles) dates this from 1976 onwards. But the story could take place more or less at any time pre-Internet.

Hurley's novel is quite short for one aimed at an adult readership (244 pages in the copy I read, at my estimate a little over 50,000 words) but supernatural horror is a genre that can support shorter wordcounts. The film follows the novel quite closely, except that Owen's (Ewan's in the novel) life and death have happened before the story starts and appear as flashbacks, while the film restructures the story chronologically. Another difference, which Hurley points out in his interview, is that there is more emphasis on what might have happened between Richard and his late father.

Daniel Kokotajlo's first feature film was the impressive Apostasy (2017), a drama set amongst a Jehovah's Witness community, informed by Kokotajlo's upbringing in that faith. While Starve Acre tells a very different story, it shares an emphasis on family dynamics, in particular its response to a tragic event which I won't spoil in the case of the earlier film. Starve Acre is set in rural Yorkshire, its bleakness well captured in Adam Scaith's widescreen cinematography, and the two leads sport creditable accents, though some Welsh inflections linger in Morfydd Clark's. The film, like the novel, works better at exploring the characters' reactions to grief rather than working out the folkloric and supernatural mechanics of the story, but it leads us to a striking final image, which comes from the novel and is well rendered on screen.

Starve Acre premiered at the 2023 London Film Festival before receiving a UK cinema release on 6 September 2024, which is followed by the present dual-format disc release.

Starve Acre is released by the BFI as a dual-format edition, Blu-ray and DVD. A checkdisc of the former was supplied for review, and is encoded for Region B only. The latter, not seen, is Region 2 PAL, so the times for the extras given below will be affected by PAL speed-up, as indeed will the feature. The film has a 15 certificate.

The film was shot digitally (no credit for which camera available, that I've been able to find) and the Blu-ray transfer is in the intended aspect ratio of 2.39:1. This is intentionally not the most brightly-lit film, with an emphasis on greys and browns, but given that this film has been in the digital realm from start to finish, there's no doubt that what you see on your television set or other viewer is what you would have seen on a cinema screen in a DCP projection.

The soundtrack comes in two options, DTS-HD MA 5.1 and 2.0, both playing in surround. There's virtually no difference between them, so the choice is yours. The surrounds are used for Matthew Herbert's score, but there are also some notable examples of directional sound – a rap on a window to screen right, and occasional panning of dialogue across the front speakers. (It's much more common nowadays to have dialogue entirely from the centre speaker, and Kokotajlo and sound designer Ben Baird talk about this in the commentary.) There is also an English audio-descriptive track in Dolby Surround (2.0). English subtitles are available for the hard-of-hearing on the feature only. I spotted one error: fifteen minutes in, Richard shows Owen a find which he calls a "Krynoid". The subtitles render this as "crinoid", no doubt having missed the reference to the 1976 Doctor Who serial The Seeds of Doom.

Commentary with Daniel Kokotajlo, Francesca Massariol and Ben Baird

This is a workmanlike commentary between, respectively, the writer/director, production designer and sound designer. As you might expect, Kokotajlo generally takes the lead, with the other two contributing most when the conversation covers their areas of expertise. There isn't as much scene-specific discussion as you might expect, but a fair amount of technical details, so this would be more of interest to filmmakers than a more general audience. That said, there are some anecdotal details to be had. Kokotajlo watched a lot of 1970s films in preparation for Starve Acre, with Serpico (1973) being a particular favourite. Its influence on Starve Acre isn't obvious, but no doubt it's in there somewhere. On the same point, and regarding Juliette and Harrie's reference to Gene Hackman mentioned above, Kokotajlo says that watching more of his work made him realise how great an actor Hackman was, given that before this he mostly associated him with Lex Luthor in the Superman films. Matt Smith dislikes mint-tasting things, so in the scene where he is seen eating After Eights, they are of the orange-flavoured variety. There is also a shout-out to Derek the Pekingese, who plays Harrie's dog Corey. Derek is a canine star in his own right due to playing Mrs Pumphrey's dog Tricki-Woo in the new version of All Creatures Great and Small, and some of his scenes had to be reshot so that he didn't steal them. The commentary finishes during the final credits, though there is a voice-over credit for engineering at the very end.

There's Something Out There (20:39)

Andrew Michael Hurley talks about his writing career. He had wanted to write from a young age, with early stories being gory imitations of Stephen King, James Herbert and Clive Barker. His first novel, The Loney, was originally published by an independent (Tartarus Press) before being taken up by a larger publisher. Starve Acre was his third novel. The name came from a big dictionary of field names and much of the process of writing the novel was coming up with a story to fit the name, with much of the folklore invented. He talks about the film's setting, near Harrogate, which pleases him as it was close to where his novel is set. He also addresses the novel and film's setting in the 1970s, which as I say above isn't heavily signposted, but does remove the possibility of smartphone use and Richard using the Internet and social media to ask advice on what is happening to him.

The Land Holds the Melody (23:26)

An extended interview with score composer Matthew Herbert. He begins by talking about his career, in particular his multi-film collaboration with Chilean director Sebastián Lelio. While Herbert talks about his appreciation for melody in orchestral film scores, which he says is somewhat out of fashion, his score for Starve Acre is dominated by textures, often produced by "found" instruments, such as the horse bones he has made flutes from. He also proudly shows us the hare skeleton he bought from Ukraine – before the war, needless to say.

On-Set Interviews

Three interviews, with a Play All option: Morfydd Clark (7:29), Matt Smith (2:48) and creature effects supervisor Sharna Rothwell and lead puppeteer Aidan Cook (16:26). The interviews follow the EPK style of text captions of the questions followed by the answers to camera. Given the short running time, the two lead actors' interviews don't dig very far, though we find out that Cardiff-based Clark knew several people who worked on Doctor Who and she had heard nothing but good word about Matt Smith, so wanted to work with him on that basis. The Hare Team interview goes further, with Cook cradling the very lifelike animatronic hare throughout. Its name is Loafy, by the way. This item would certainly be of interest to anyone interested in special effects, which on this film were mostly practical. No doubt other films would have had CGI hares.

Behind the Scenes

Two items with a Play All option. First there is some behind-the-scenes footage (4:58) with no commentary. Interesting to see this, with the camera and boom mike in action, but not more than a one-watch item. Also there is a self-navigating behind-the-scenes gallery (5:29), with stills (colour and black and white) and storyboards.

The Sandwich Scene, with optional director commentary (1:25)

A scene between Harrie and Juliette which Kokotajlo in his commentary says he liked, but which was removed early on, to the extent that what we see has not been fully edited.

The Hare, a Folk Song (1:05)

Sean Gilder, who plays Gordon in the film, reads from Hurley's novel.

Stills gallery (10:11)

As it says, self-navigating, all the stills in colour. For other production documents, you'll need to see the other gallery under the Behind the Scenes sub-menu.

Theatrical trailer (1:39)

If a trailer is reasonably short, you can tell that its makers have a reasonable idea as to how to sell their film. In cases where they're more unsure, they might add as many scenes as they can in the hope that something sticks. Therefore, this is an effective trailer, which you have the choice of listening to in DTS-HD MA 5.1 or DTS-HD MA 2.0 (in surround).

Booklet

The BFI's booklet, available with the first pressing of this release, runs to twenty-eight pages. It begins with "'Tis part of his game...To vary his name'" by the writer/director. Kokotajlo begins by saying how much religion shaped his formative years and his interest in how Christianity has assimilated pagan traditions. He goes on to talk about the symbol of the hare and how it features in the film, which he describes as "an ode to this wondrous creature".

"Approaching Starve Acre" by Catherine Spooner begins by describing the opening scenes, of landscape and the farmhouse in louring weather, emphasising that this story, like to give one example Wuthering Heights, is named for a place rather than any of the characters. Also the first shots of the film are of the landscape rather than the people in it. The essay then gives a brief summary of folk horror and its antecedents on the large and small screen. Richard and Juliette are a typical middle-class couple who headed off to the countryside in the early 1970s, a plot arc common to quite a few entries in the genre. Spooner then discusses the specifics of the films' 1970s setting and in particular Juliette's part in a "female gothic" narrative.

Dr Adam Scovell contributes "The British folk horror revival" which picks at what he calls "the ever-awkward question" of what constitutes the genre. This includes not just the 1960s/1970s "unholy trinity" mentioned above, plus antecedents going as far back as Benjamin Christensen's Witchcraft Through the Ages (Häxan, 1922). The genre's currency increased with the availability on DVD of some prime televisual examples from the 1970s, often disturbing a generation of youngsters, such as Children of the Stones (1977), Sky (1975) and The Owl Service (1969), and more adult versions coming out on disc from the BFI, such as the Ghost Stories for Christmas, the surviving episodes of Dead of Night (1972) and the Play for Today Robin Redbreast (1970). Scovell then talks about a revival in the genre, partly brought about by this interest, such as films directed by Ben Wheatley (particularly Kill List (2011), Sightseers (2012) and A Field in England (2013)) and other films and television. In the latter case there is the recent revival of the Ghost Stories for Christmas by Mark Gatiss, who could be said to have defined the genre in his 2010 TV series A History of Horror.

The booklet also contains a cast and crew list for Starve Acre, and notes on and credits for the extras on the disc.

Starve Acre arrives on disc as part of the interest in folk horror, and is not as far removed from Daniel Kokotajlo's debut feature Apostasy as it might seem at first. While the extras on this BFI disc are more specific to the film at hand, so no appropriate items curated from the archive this time, but the film is well served.

|