|

I’m not old enough (when you get to my age, you enjoy occasionally getting the opportunity to write that) to have experienced the initial impact that Italian neorealism, the French Nouvelle Vague and British New Wave had on the worldwide film scene, the pioneering works of each having been made before I came into existence. But as someone whose early film diet consisted largely of Hollywood movies and a sprinkling of popular British titles, I do still remember the eye-opening impact the likes of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Bicycle Thieves and Les quatre cents coups had on me when I first saw them. Such films gave me the feeling, perhaps for the first time, that I was watching people on screen who were close to how they really were rather than performd and stylised interpretations of them. The influence these films had on 70s Hollywood and even independent cinema was considerable, bringing a welcome degree of realism to some of the key dramas and thrillers of the period. But what of American neorealist cinema as a movement? The figure most commonly associated with it is John Cassavetes, and with good reason. His 1958 Shadows was a genuinely pivotal work of American independent cinema, but it was his 1968 Faces that became the movement’s cheerleader. And yet the very same year that Cassavetes’ electrifying film was startling critics and audiences and winning festival prizes, a neorealist-influenced micro-budget feature made by an Ohio-based film lecturer and a group of his students and graduates was struggling to find an audience and ended up being recut and retitled for distribution on the exploitation circuit. Only years later was it restored to its original cut and recognised for the achievement it unquestionably is.

Although very much realist-influenced work, Spring Night Summer Night gets off to what I can’t help thinking is a deliberately metaphorical start, as Carl (Ted Heimerdinger), the eldest son of a poor rural Ohio farming family, blows a hole in the wing mirror of his father Virgil’s tractor, symbolically foreshadowing the impact his later actions will have on his angry parent. We then join the family at supper for a scene that is primarily about getting to know them a little, and in the course of the mealtime conversation key snippets of information are dropped so casually that their significance only really registers on a second viewing. It’s made clear from the off that Virgil (John Crawford) is fed up with Carl’s lack of respect and that Carl is fed up with the way things are at home, an urge to break away that seems to have to spread to his slightly younger sister Jessie (Larue Hall). In an almost throwaway comment – one confirmed and expanded on later in the film – the mother, Mae (Marjorie Johnson), reveals that Carl is Virgil’s son from a previous marriage and that in her view the boy has never really warmed to her.

Late in the meal an irritated Jessie scurries out of the room, but against expectations the still disgruntled Carl stays and even dutifully collects the empty plates when the meal is complete. When he opens the door to the kitchen, however, he sees his sister taking a bath there and thus returns to his seat and asks one of his younger siblings to clear the table instead. This is a key moment, albeit one that will nor register as so until later and is all about the length of Carl’s pause before turning away and closing the door. When he sees Jessie he doesn’t instinctively avert his eyes at the sight of his unaware sister’s naked back but instead watches her, just for a few seconds, before turning away. Is he curious, surprised, or is there something more problematic happening here? Many young boys will get their first fleeting glimpse of a naked female when they catch sight of the sister getting changed or bathing, but with both Carl and Jessie in their late teens, this moment takes on an altogether different air.

When the father breaks a promise to take the mother dancing, she instead hitches a lift to the venue with Carl, who also, we can presume from what follows, agrees to take Jessie with him and drop Grandma off at her prayer meeting. At the barroom dance, Jessie dances with local boy Tom Morgan (Ron Parady), a move that clearly aggravates the watching Carl, who responds by angrily pulling the two apart and having a go at Tom, which nearly sparks an all-out fight that is only curtailed by the quick intervention of others. Jessie runs out into the night and Carl Pursues her in his car, and this may or may not be where you should stop reading if you’ve never seen the film and know very little about it. My indecision on this point arises from the fact that, despite the obvious advantages of going in cold, if you’re going to consider splashing out for this disc then you’re likely to read a fair bit about it before doing so, and most reviews I’ve seen and even the one-line plot summary on IMDb spell out exactly what happens to both characters after this scene. And it is worth discussing, but while it does occur early in the story, if you’ve managed to avoid stumbling over the details of what unfolds and wish to remain in the dark until you see the film itself, then skip to the final paragraph of this review or click here to scroll down the page.

What happens is that Carl catches up to Jessie and forces his struggling and protesting sister into the car, then drives off towards what I initially presumed would be home. But something happens before they get there, something whose portrayal in the film leaves a key detail shrouded in ambiguity. As they drive, Jessie is shown to have calmed down a little and is conversing tersely (but crucially not fearfully) with Carl, a conversation that is observed through the windscreen from outside and whose content we are prevented from hearing. The car speeds off and we then cut to a close-up of Jessie’s face. She’s no longer in the car and appears to be lying on the ground outside, staring blankly into space in a manner that is open to multiple readings, which is followed by a wide shot of Jessie walking back to the car doing up her dress, which pans to reveal Carl in the foreground pulling his trousers up over his naked behind. It seems quite clear that the two have just had sex, but not whether it was a consensual act. Jessie’s wide-eyed expression and her distance from Carl as she walks back to the car make it hard to be sure whether she’s trying to process what has just happened, is deeply shamed by their taboo-breaking actions, or is a shaken victim of rape on Carl’s part. And if you’re expecting a quick resolution to that conundrum then you’re going to be out of luck. Take note of that title. This is exactly where it starts to make sense.

In the blink of an edit, a few months have passed and the hitchhiking Carl is riding in a stranger’s car and heading back to home turf, from which we later learn he fled without a word to anyone following that fateful night. He’s cautious about approaching the farm, where family life has been disrupted just slightly by the fact that Jessie is now very visibly pregnant. Despite being repeatedly pressed on the matter, she flatly refuses to reveal the identity of the baby’s father to anyone, which is not sitting well with the temperamental Virgil, who remains determined to find out who it is. Whether Carl will actually approach the house and confront the results of his actions is initially uncertain, and how both he and Jessie will react if he does so could have implications for them both and indeed for the whole family.

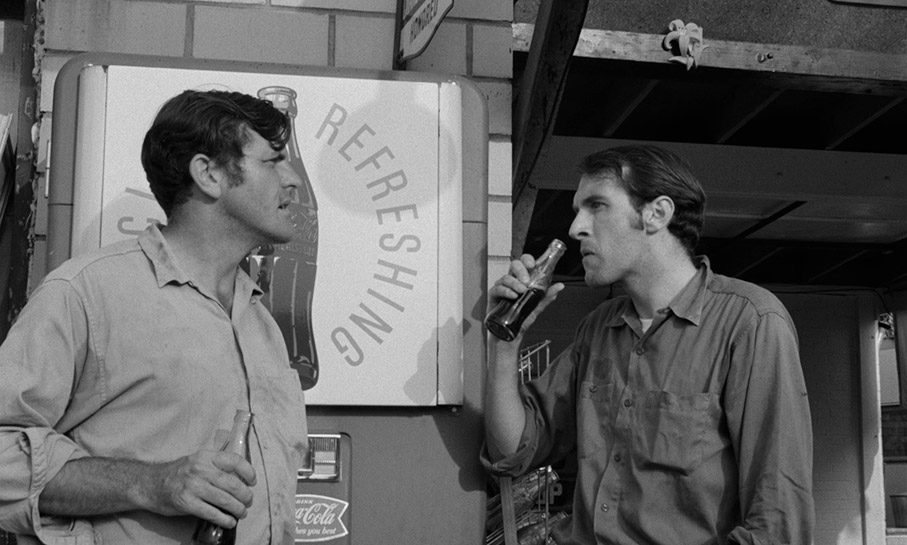

On the surface, this has all the ingredients of a taboo-busting exploitation movie, particularly given the year of its release and its reported budget of just $25,000. But as you probably picked up from the opening paragraph, the approach taken by co-writer and director Joseph L. Anderson – in the first of only two features bearing his name – has more in common with Italian neorealism than late 60s Roger Corman. And while there are a couple of elements that briefly skate close what have become too-familiar components of movies even partly set this region, nothing about the way the people or the community here are portrayed feels remotely condescending or artificial. A key factor on this score is a string of convincingly low-key performances who unforced naturalism initially had me suspecting that the principal cast was comprised of talented non-professionals, a supposition knocked firmly on the head by the riveting and revealing barroom monologue delivered by John Crawford as Virgil in which he looks back longingly on his wartime army years, then expresses his regret for the better life he feels he should have been able to provide for both of his wives. In the extras it’s confirmed that all of the lead players were experienced stage actors but that the background characters in the evening barroom dance scene were locals who were plied with free beer and encouraged to enjoy themselves whilst the actors performed their scenes in their midst. Visually the film also echoes the Italian neorealist works from which the filmmakers drew their inspiration, the naturalistic lighting and mix of static and handheld camerawork intermittently augmented by subtly effective camera moves and even the occasional and unexpected point-of-view shot, the most eye-catch of which takes the viewpoint of a polaroid camera as it’s lifted and framed. The drama is also richly textured with imagery of the local landscape and community, giving the film an ethnographic quality that some who live in the region have commended director Anderson for accurately capturing.

It’s in the second half that plot takes an almost complete back seat to character, allowing Anderson and his cast to captivatingly explore how relationships in the family have changed over time and to speculate on where they may be heading next. As Virgil continues his quest to identify who it was who knocked his daughter up he also wearily tracks down the absent Mae, whom he finds drinking with her flirty friend Rose (Mary Cass) and Rose’s latest pickup George (Miles Gibbons), and who responds to Virgil’s demands that she come home with almost bored disinterest. Tellingly, when Rose is not put off by Virgil’s initial hostility towards her and tries to come on to him out of Mae’s sight and earshot, he soundly rejects her – he may be angry at Mae’s actions but is still, in his gruff way, devoted to her. Later, in the aforementioned monologue, he lays out to an unidentified drinking companion the full extent of his regrets and touchingly makes it clear that despite frustration at Mae’s airs and graces and her daytime drinking, he believes that the blame for lies firmly at the feet of his own fate-shaped failings. Carl and Jessie, meanwhile, meet up and reconnect but have issues of their own to resolve about how they actually feel about each other and the moral implications of their actions, which Carl then attempts to justify by suggesting that Mae’s reputation for sleeping around may mean that Virgil is not her father and that they are not blood relatives after all. In another movie, I have no doubt that this would be confirmed and be used to take the edge off audience discomfort at the very notion of incest, but here seems likely from the off to remain unresolved.

Spring Night Summer Night caught me by surprise in the very best way. I knew little about it and decided not to read any synopses or reviews before sitting down to watch it. On my first viewing I was captivated by the handling, the setting, the characters and the storytelling, but on the second was better able to appreciate the film’s arresting attention to detail and appreciate the subtle sophistication of its approach and what it was saying about family and relationship and generational disconnect. And despite its microbudget and a crew consisting primarily of students and graduates, this is one seriously well-made film. The 35mm cinematography by David Prince, Brian Blauser and Art Stifel is consistently crisp and professionally composed and lit, while Joseph Anderson and Franklin Miller’s editing is thrillingly vibrant in the barroom dance sequence but knows when to slow down and just let conversations play out without the need for back-and-forth cutting to artificially accelerate the pace. It even has an ending that Iould swaer was an influence on an altogether more widely seen film had the two not been in production at roughly the same time. It’s a work whose unforced naturalism hooked me from the start, but a couple of viewings later I was left in no doubt that this is one film that absolutely deserves that too-often bandied-about accolade of criminally overlooked gem.

Spring Night Summer Night has been restored in 4K from the original 35mm negatives by Peter Conheim and Ross Lipman of the Cinema Preservation Alliance, with support from filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn, who I’m assuming is also something of a fan. The result is an utterly gorgeous 1.66:1 transfer that makes an absolute mockery of the notion that a low budget must automatically result in rough-and-ready visuals. The image is consistently sharp with an excellent level of detail and beautifully balanced contrast, with crisp black levels and a generous tonal range on lit areas of screen, really shining in the daylight scenes. Just about all traces of dust and dirt have been removed and a fine film grain is still visible. Terrific.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has also been restored, and while there are some restrictions in the dynamic range that do limit the finesse of the treble and bass, the results are still clear and free of obvious faults or damage, clear enough indeed to be just able to pinpoint some of the sequences where dialogue was rerecorded in post.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are present, as expected.

50 Years Later (24:23)

A retrospective documentary on the making of the film built around interviews with writer-producer-director Joseph Anderson, writer-producer Franklin Miller, sound mixer Tom Peterson and actors Ted Heimerdinger, John Crawford and Larue Hall. They look back at how the film came to be, the tragic death of original collaborator Douglas Rapp, and the process of making the film and what happened to it afterwards, where new material was added, some scenes were altered and the title was changed to Miss Jessie is Pregnant. The actors talk about their characters and have very positive memories of making the film, and Anderson reveals that he was approached by people who live in this region of Ohio to assure him he had painted an accurate portrait of their lives.

I’m Goin’ to Straightsville (14:07)

Writer-producer Franklin Miller travels with Peter Conheim – who appears to be the driving force behind most of the extra features here – back to Shawnee, Ohio, to revisit the locations at which the film was principally shot, which are often presented side-by-side with relevant footage from the film. Again, of considerable interest.

In the Middle of the Nights (13:19)

A featurette written, edited and narrated by Ross Lipman, in consultation with the aforementioned Peter Conheim, that explores the changes made to the film in the course of its transformation at the hands of distributor Joseph Brenner from Spring Night Summer Night to the more exploitation-friendly Miss Jessie is Pregnant. For those who have never seen the recut version – and I’m guessing that’s most of us – this is hugely informative viewing.

Cleveland Cinematheque Q&A (47:15)

A post-screening on-stage Q&A hosted at the Cleveland Institute of Art Cinematheque on 17 April 2016 featuring Joseph Anderson, Franklin Miller, Judy Miller (Franklin’s wife and the film’s continuity supervisor), Ted Heimerdinger, Larue Hall, John Crawford and Tom Peterson. While there is some inevitable crossover with other extras here, this very enjoyable extra is still rich with new stories and information about the making of Spring Night Summer Night. Anderson is keen to point out is essentially a student film due to the makeup of the crew, though the host then steps in to note that if so then it’s one of the best-looking student films he’s ever seen. Peterson talks more about the mixing of the film and his own film company than he does in the documentary, Anderson reveals a trick he learned for getting reluctant participants to signs release forms, and Miller tells an entertaining story (no big spoilers here, but hop t the next extra if you want to be sure) about keeping scripts out the hands of locals, whom they suspected would strongly disapprove of the subject matter, only to have one go missing and the film’s content to quickly become common knowledge. When Miller nervously questioned one of the town’s residents about his views on the film’s more controversial content, the person in question apparently responded, “Oh, that goes on all the time.” There’s lots more here, all of it enthralling.

16mm Behind-the-Scenes Footage (62:57)

A substantial collection of mute 16mm footage of the making of the film shot by, according to Franklin Miller, anyone prepared to pick up a camera, and with a crew of photography students, there appear to have been several willing and with the necessary skills to do so. You have the option to just watch the footage silent or with a new commentary by Franklin Miller and Peter Conheim, and that’s absolutely the way to go, as Miller provides a wealth of background information on the filming being observed, on which he is most effectively prompted by Conheim. As someone who has shot a no-budget feature that involved all manner of creative workarounds to get the shots we wanted, I was fascinated by this.

Joseph L. Anderson Short Films

Three of the short films made by director Joseph L. Anderson and his then student Franklin Miller before they started work on Spring Night Summer Night. All three are shot silent and scored with music (by Miller, as it happens) and all are inventive and really well made.

Football As It is Player Today (1962) (5:40)

An American football match, together with its preparation and its aftermath, are recorded in high-speed time-lapse whose pace is accelerated further by Franklin Miller’s breathless bluegrass score. A fascinating work that is bristling with eye-popping imagery and whose effectiveness stems from the chosen camera angles and having the action it depicts play at such a speed. This is at its most striking on the ant-like trails of spectators arriving at the stadium, the regimented parking of cars and the carefully choreographed work of an army of mid-game musicians. If Anderson had spread his net wider and expanded the concept to feature-length he’d have beaten Koyaanisqatsi to the post by twenty years. Even the title graphics are inventively devised.

How Swived (1962) (5:26)

Time-lapse imagery and Appellation bluegrass are again put to creative and effective use to paint a portrait of the average day in the life of a busy housewife and a mother of three. This is bookended by normal speed sequences of her husband going off to work and coming home and sitting down all tuckered out, the poor dear, while his wife looks on with just a whiff of contempt in her stance and expression.

Cheers (1963) (5:02)

Not a forerunner to the Boston bar comedy series but an impressively shot and edited portrait of a high school basketball cheerleading team, once again filmed mute and scored with bluegrass music that is sometimes sublimely matched to the actions and dancing of the girls.

Image Gallery

66 high quality behind-the-scenes and promotional photos shot by Jon Webb, who I believe was one of the photography students recruited to work on the film. Several of these feature in other extras on this disc.

Booklet

Indicator booklets are always a treasure trove of articles, opinions and analysis, but they move into the realm of essential reading when they accompany a film you’re really a fan of, as is the case with little me and Spring Night Summer Night. Following the credits, this one begins with an excellent essay on the film by filmmaker, writer and programmer Ian Mantgani, one that inevitably undermines my review just a tad by highlighting some of the very same things but exploring them in considerably more detail and covering far more ground. Next is a piece by television and film producer Glenn Litton on meeting Joseph Anderson and interviewing him and his collaborators for the 50 Years Later documentary detailed above, which was produced by Litton’s production company DocuThis. This is followed by a compellingly detailed breakdown of the process of restoring the film by Peter Conheim, and a really useful piece by Jeff Billington looking at the career of exploitation film distributor Joseph Brenner, whose company altered and repackaged the film as Miss Jessie is Pregnant. Finally, we have credits for and notes on the three short Joseph Anderson films on this disc, which I can’t say I was completely surprised to learn are known as ‘The Bluegrass Trilogy’, as well as information on the transfers. As ever, the booklet is nicely illustrated with still and a rather nice minimalist poster for the film that is also the basis for the Blu-ray cover.

Over the course of three viewings I fell completely in love with Spring Night Summer Night, a film whose quiet boldness, authenticity, character-centric storytelling and filmmaking chops completely won me over, and I absolutely take my hat off to Joseph Anderson and Franklin Miller for their justified conviction that they and a crew of photography students could make a significant and impressive feature debut. The film is making its UK Blu-ray debut here and I couldn’t ask for a more comprehensive package – the transfer is immaculate, and the special features provide all the supporting material you could hope for. As ever, it will prove a matter of personal taste and I’m aware that this is at the root of my fondness for the film, but this already looks like being one of my favourite disc releases of the year. Highly recommended.

|