|

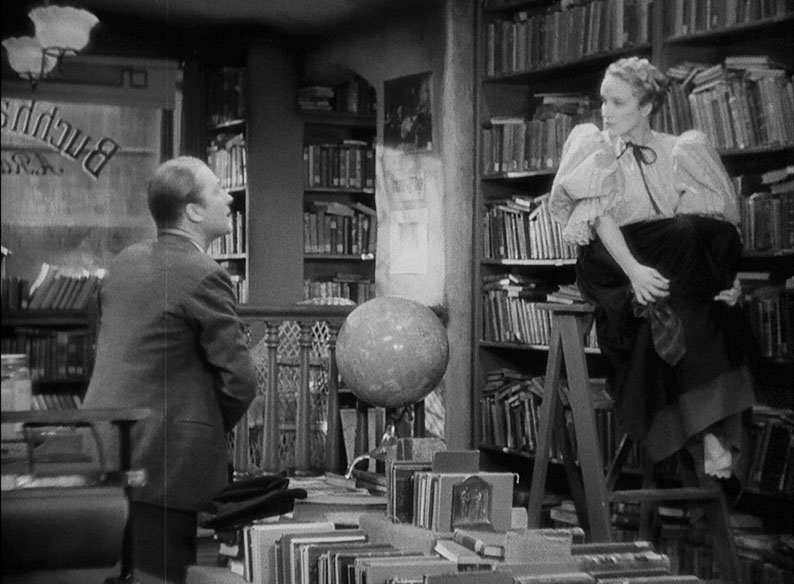

When her father dies, Lily (Marlene Dietrich) moves to Berlin to live with her aunt (Alison Skipworth). Lily meets Richard Waldow (Brian Aherne), a sculptor who lives nearby, and eventually she poses for him. They fall in love, but Richard has a rival in the shape of one of his clients, Baron von Merzbach (Lionel Atwill).

The Song of Songs, released in 1933, is a film directed by Rouben Mamoulian and starring Marlene Dietrich, both with their names in larger type than other people’s in the opening credits. Ninety years on, it tends to be overlooked compared to the films which preceded and followed it in both of their careers. However, it is certainly worth more attention.

Dietrich had made five films in a row with director and mentor Josef von Sternberg, The first of these, The Blue Angel (1930), her first talkie, shot in her native Germany in both German- and English-language versions, had made her reputation. This had brought her to the USA and Paramount and she and von Sternberg had made Morocco the same year, Dishonored the following year and both Shanghai Express and Blonde Venus the year after that. By 1933, both Dietrich and von Sternberg were in contract negotiations with Paramount, and the lack of box-office success of Blonde Venus led to the suggestion that they part company, if just for the one film. That film was The Song of Songs, which had been originally intended for Tallulah Bankhead. The Song of Songs was based on a 1908 novel (Das hohe Lied in the original German) by Hermann Sodermann and a 1914 play based on the novel by Edward Sheldon. Both English and German titles refer to the book of the Old Testament, which Lily quotes in the film. The novel had been filmed twice before in silent days, in 1918 with Elsie Ferguson under the present title and in 1924 as Lily in the Dust with Pola Negri. Both of these silents are now lost, but Paramount intended to make a sound version of the story – as it turned out the only one, other than a 1973 five-part BBC television serial starring Penelope Wilton, of which the first and last episodes are lost.

At first Dietrich did not want to make The Song of Songs without von Sternberg and was threatened with legal action as a result, but von Sternberg smoothed the waters and approved Rouben Mamoulian to direct. And so this was the only one of the eight films that Dietrich made between 1930 and 1935 which was not directed by her most famous collaborator. Dietrich was still not entirely happy, saying on set on the first day of shooting, “Jo, where are you?”. That was according to her daughter Maria Riva and no doubt didn’t put her new director at ease. (The six Paramount Dietrich/von Sternberg films were released by Indicator as a limited edition box set which is now sold out, but they are available as separate standard editions.) In her von Sternberg films, she often played an exotic woman, a creation of her director’s lighting and staging and the costume design. Here, she begins as an innocent, though that changes as the story progresses and she is in more familiar mode, or close to it, later on.

As for Mamoulian, he was as famous as any director was in Hollywood at the time. (Just look at the trailer for his previous film, Love Me Tonight, which heavily emphasises his contribution.) Born in 1897 in what is now Georgia, he arrived in the USA in 1923 and was directing on Broadway four years later. Two years after that, he made his first feature film, Applause, hired amongst other reasons for his facility with dialogue as a stage director, which he continued to be while he made films. Whatever his reputation as a director might be now, even his detractors acknowledge him as an innovator. When many early talkies abandoned the moving camera of late silents, resulting in very visually static films, Mamoulian embraced it, hiring as many as ten men to shift the camera on set. This began a great run of films, followed by the crime drama City Streets (1931), a definitive take on Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (also 1931), possibly his masterpiece, and the delightful musical comedy Love Me Tonight (1932). While his technique is not as overt as it was in Love Me Tonight, in the service of a more serious drama in The Song of Songs it’s still there. He continues to move the camera, uses superimposition at key points and opens with a shot that could have come from a contemporary or recent Soviet movie.

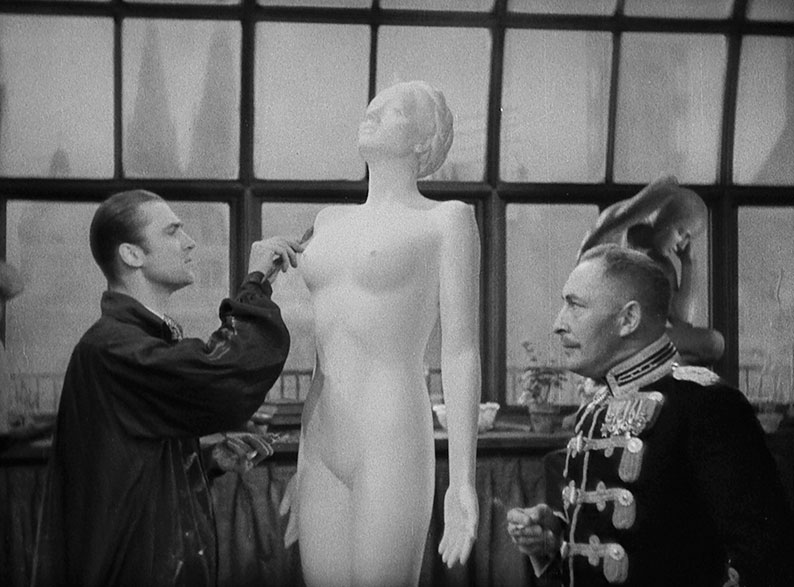

The Song of Songs is a Pre-Code film. The Pre-Code era runs from 1930 when Will Hays, after concerns at the contents of motion pictures (and, with the introduction of sound, the likelihood of salacious dialogue), drew up the first version of his code. This, comprising a list of “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls” was largely ignored by the studios when audiences were still flocking to their films, in search of escapism in Depression times. They still had state censorship boards to contend with, though. The Song of Songs could not have been made a year later than it was, as the Production Code was enforced, affecting the films the major studios made for more than the next three decades. The reason for this was the sculpture of Lily which Richard makes – fully nude, often full-frontal (though not going so far as sculpted pubic hair), nipples on proud display.

While this isn’t the only Pre-Code film to feature its leading lady undressing to her underwear – Lily’s aunt comments on the number of petticoats she has to remove – nudity was another matter. You can see occasional nudity in the Pre-Code era, usually fleeting, but not from a major star like Dietrich. Mamoulian makes much use of Richard’s sculpture of her, partly to get round potential censor objections, cutting or panning away from Lily undressing to the sculpture or a drawing, mimicking her actions (crossed legs, for example). Later in the film, Mamoulian stages a scene between Richard and Baron von Merzbach with the sculpture in the middle, the woman who has come between the two men. Dietrich had it in her contract that she would not pose nude and the only part of the statue which would accurately represent her would be the head, but later she did in fact pose for the rest of it. At one point, Richard remembers Lily’s voice, and Mamoulian has this over a close-up of the statue. At another, Richard even caresses the breasts of the uncompleted statue, as clearly an indication as to what is on his mind as you could get. This was from a director who had certainly pushed the envelope of Pre-Code sexual suggestiveness before now.

Clearly, the Production Code Administration did not find this representation of nudity acceptable after the Code was enforced from 1 July 1934. Films from before then had to be vetted to decide if they could remain in exhibition or could be reissued. Love Me Tonight was cut for this reason, and unfortunately the cut version is all that survives. This nude statue was so prominent in The Song of Songs, that the PCA clearly found it impossible to make cuts to have the film be fit for further viewing, so it was withdrawn and not seen for many years.

Fredric March and Herbert Marshall turned down the role of Richard before Brian Aherne was cast. Aherne had begun his career on stage and screen in the country of his birth, the United Kingdom, but had relocated to America at the beginning of the 1930s. The Song of Songs was his American film debut, and he’s certainly overshadowed by the leading lady, though having an affair with her may have made up for that. He would play leading roles later in the decade. Opposite Dietrich and Aherne was Lionel Atwill. Atwill specialised in villains (see his nasty piece of work in Murders in the Zoo (1932)), often with an edge of perversity, and that’s to the fore in The Song of Songs. Josef von Sternberg must have taken note, as he cast Atwill in his final film with Dietrich, The Devil is a Woman. Atwill even resembles von Sternberg.

The Song of Songs was not a success at the box office and attracted tepid reviews. Dietrich went back to von Sternberg for the final two films of their collaboration. Mamoulian went from Dietrich to another iconic leading lady imported from Europe, Greta Garbo, in Queen Christina, one of her and his greatest films. With its return to availability, The Song of Songs can be reassessed and it’s qualities recognised.

The Song of Songs is released on Blu-ray by Powerhouse, spine number 265 in the Indicator series. The disc is encoded for Region B only. The film had an A certificate in British cinemas in 1933. There’s no indication from the BBFC if the film was cut or not, but the running time on the website (84:00) is nearly five minutes shorter than the version on this disc (89:57). Nowadays, nude statuary no longer frightens the horses and The Song of Songs carries a U certificate.

The film was shot in 35mm black and white and the Blu-ray transfer is in the correct Academy Ratio, 1.37:1. The transfer is based on Universal’s HD restoration of 2008. The results are a little soft, no doubt reflecting Victor Milner’s cinematography which for much of the film is more greyscale with not so many actual blacks and whites. Grain is natural and filmlike.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. It’s genuinely clear and well-balanced, with a little hiss as you’d expect from a sound film of this vintage. There are optional hard-of-hearing subtitles for the main feature. I didn’t spot any errors in them and they ably convey Lily’s mispronunciations in the scene where she is learning French. The French dialogue and the lyrics of a German-language song Lily sings are rendered as French and German – they aren’t translated as they wouldn’t have been if you’d seen the film in a cinema back in 1933, in an English-speaking country anyway.

Commentary by David Del Valle

Recorded in 2020, Del Valle gives an enthusiastic and appreciative commentary, going through the inception and production of the film without being too scene-specific and without many dead spots. He gives details of the careers of star and director putting the film into the context of their careers, and reads the latter part of the film as a horror, with Lily subjugated by her new husband the Baron. Del Valle oddly adds letters to the names of director and co-star, pronouncing their names “Mal-moulian” and “Ath-erne”. This is also a track where you hear the commentator say, “Look at those perky breasts!”

The Mamoulian Touch (32:22)

Geoff Andrew is a long-time champion of Rouben Mamoulian. As he says in his equivalent piece on Indicator’s Blu-ray of Love Me Tonight (released after this one) but not here, he programmed a retrospective of the director’s films at the BFI Southbank in London. This item begins with advice of plot spoilers. If you watch both interviews, there will be some repetition as Andrew talks through Mamoulian’s career both before the film on the disc and after. Mamoulian’s purple patch ended with the next film he did, Queen Christina, and you could make a case that later films were not up to the same level, though they did include his directing the first feature film in three-strip Technicolor, Becky Sharp (1935), and he certainly did make considerable use of colour in that film. He was taken off two films, Laura (1944) and Cleopatra (1963), replaced by Otto Preminger and Joseph L. Mankiewicz respectively, and his final film was the musical Silk Stockings (1957). He died in 1987. Andrew also talks about Dietrich’s career and this film’s place in her own career, though his emphasis is on the director. He talks about Mamoulian’s “touch” (hence the title of this piece), which he sees as at least equal to the touch legendarily possessed by Ernst Lubitsch. He also compares this film about the making of an artwork with a much later one able to include more explicit nudity, Jacques Rivette’s La belle noiseuse (1991).

Lux Radio Theatre: The Song of Songs (53:29)

This radio adaptation of the film followed three and a half years after the film’s release, broadcast on 20 December 1937. Following an initial caption, it is presented on the disc as audio-only over a black screen. Given the running time, this is inevitably a cut-down version of the story. Marlene Dietrich and Lionel Atwill reprise their film roles, but Douglas Fairbanks Jr steps in for Brian Aherne. The producer is none other than Cecil B. De Mille, who speaks to the audience at the start, announcing that Dietrich is now an American citizen. He also says that her next film would be an adaptation of the Terence Rattigan play French Without Tears, which she had seen in London. This didn’t in fact happen, and French Without Tears was filmed in Britain in 1939, directed by Anthony Asquith and starring Ray Milland and Ellen Drew. After the play, De Mille talks to the cast. Dietrich simply wishes the listeners a Happy Christmas but De Mille shares jokes with Fairbanks about their boats and Atwill talks about his stamp collection. We end with a plug for the production next Monday night, that is the 27th, Beloved Enemy, with Madeleine Carroll and the man who hadn’t returned to his film role for The Song of Songs but would for this, Brian Aherne.

Trailer (2:41)

This can’t be accused of underselling the film it’s meant to advertise: “Bold! Daring! Exotic! The most important picture you will see this year! One of the world’s great love stories comes to the star who can make it live!” And that nude statue gets several shots in this trailer, which also includes part of one of the songs its star sings in this non-musical. Rouben Mamoulian barely gets a look-in.

Image gallery

Thirty-one of them, accessed via the NEXT button on your remote: stills (all black and white), lobby cards (black and white and colour) and a poster.

Booklet

The booklet with this limited edition runs to forty pages. It begins with an essay by Rick Burin, “I Called Him, But He Gave Me No Answer”. This alludes to Dietrich’s plaintive enquiry on set which I mention above, quoted at the start of the essay. Burin addresses the elephant in this particular room, that this is the only one of Dietrich’s first eight sound films not directed by von Sternberg has contributed to its relative neglect. He sees The Song of Songs as a possible origin story for Dietrich’s more familiar persona. We see the formation of the “cynical, sleepy-eyed vamp,” as he puts it. Burin discusses the film’s origin, with Paramount in deficit and the hope of a vehicle for its major star before her contract was up for renewal to make up for the failure of Blonde Venus. It would also enable them to move her away from her regular director, who was often difficult and by no means a good commercial bet. Mamoulian’s role in the film is also discussed, at first reluctant to take it on but agreeing when told that he had the approval of both the star and her previous director and mentor. Burin then spends some time on the film’s Pre-Code eroticism, in particular that statue. Ultimately, Burin defends the film from its latterday reputation – neither star nor director liked the result – and even considers it among Dietrich’s best work.

From the New York Daily News of 23 August 1933 we have the “Tintypes” column by Sideny Skolsky. This is a profile of Rouben Mamoulian which, the booklet rightly says, “is as eccentric as its subject”. At this point, Mamoulian was directing Queen Christina, “the new Garbo flicker” and the article could possibly be retitled “Twenty-one Things You Might Not Know About Rouben Mamoulian”, such as the fact that he owned seventeen suits, fourteen of them in blue serge, all bought in London.

On to 1966, and Andrew Sarris interviewed Mamoulian for his book Interviews with Film Directors. This extract covers his stage career and his cinema debut with Applause. He talks about his innovations in the latter, such as recording one scene with two audio channels and his moving of the camera over the objections of the cinematographer, George Folsey. (Folsey made 162 films and was Oscar-nominated thirteen times, a record without ever winning, so was clearly not chopped liver.) Another extract from this interview can be found in the booklet for Indicator’s other recent Mamoulian release, Love Me Tonight.

Also in the booklet are some of the critical responses to the film: a middling review from The Guardian, one from the New York Times praising Mamoulian’s visual style, and Tom Milne’s later reassessment in his 1969 book on the director.

Often overlooked compared to earlier and subsequent films of its star and director, The Song of Songs is worthy of reassessment for both their contributions. It is as you would expect well presented on Blu-ray by Indicator.

|