|

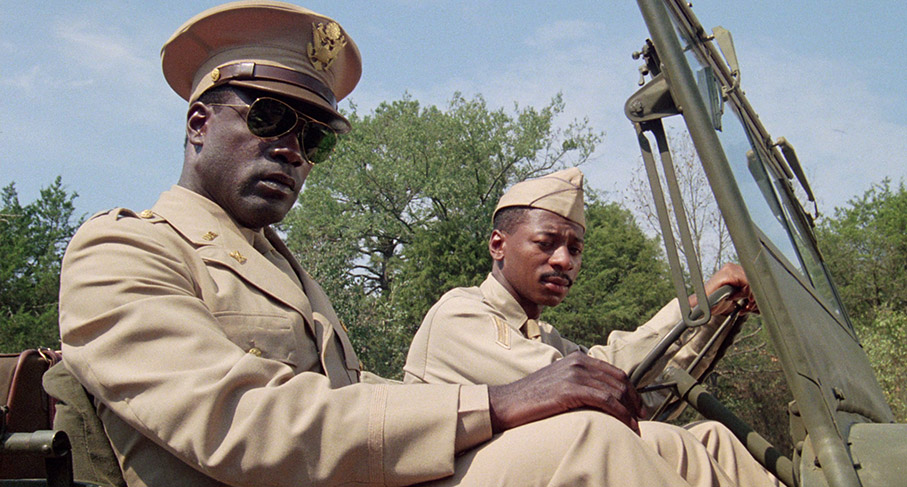

There’s a moment that comes in the 1984 A Soldier’s Story that is so deliciously cool that, despite an opening murder of an African-American army sergeant and a gruff conversation with an uncooperative colonel, made me wonder on my first viewing whether the film was a straight out drama or one with intentional comic overtones. It occurs when black US Army Captain Davenport (Howard E. Rollins Jr.) has his first meeting with white counterpart Captain Taylor (Dennis Lipscomb), and Taylor, a little unsettled by Davenport’s aviator sunglasses, asks him irritably to remove them. “I like these,” Davenport stonily replies, “They’re like MacArthur’s.” It’s a retort that put the widest of smiles on my face and I took an instant liking to this man. A short while later, Tayler irritably complains that with Davenport investigating the murder they’re unlikely to get anywhere, which prompts Davenport to stand up and bark, “Like it or not, Captain, I’m all you’ve got! Your orders instruct you to cooperate!” In its way, it’s this film’s “They call me Mister Tibbs!” moment. How appropriate, then, that A Soldier’s Story was directed by the very same man who earlier helmed the film in which that gloriously defiant declaration was made.

The murdered man is Sergeant Waters (Adolph Caesar), who in the opening scene is shown to be getting shit-faced drunk in a bar, and as he makes his way back to the army base he is accosted by an unknown figure and shot dead. We only catch the last part of this confrontation, by when his face has been bloodied and a pistol is already aimed at his head. Back at the barracks, the members of the all-black company that Waters was a part of are convinced that he was killed by local Klansmen, but Captain Taylor warns them against making unproven assumptions and bans them from going into town and stirring up trouble. When Davenport arrives to investigate the killing, everyone is surprised, primarily because they have never encountered a black officer of his rank. The soldiers are initially fired up by the sight of a black captain, but as he starts to question them it quickly becomes clear that far from being a beloved member of the company, Sergeant Waters was disliked by almost everyone, and few seem to be really mourning his demise.

A Soldier’s Story is in essence a film about racism dressed in the coat of a whodunnit murder mystery set in Louisiana in 1944, and one of its principal strengths is that these two elements are closely intertwined and do not in any way detract from each other. The situation into which Davenport walks is racially divisive by its very nature, an all-black regiment commanded by white officers that has been assigned a lowly job – generating smoke cover to hide the movements of other (white) troops – and whose recruits are being seemingly prevented from participating in a war they are all itching to be part of. Local attitudes and the rarity of black officers of any rank at the time is also brought home early when Davenport’s bus reaches his stop and the driver alerts him to this fact with undisguised contempt for his only non-white passenger, ignoring his uniform and calling him “boy” in that loathsome manner once popular with Southern racists. Once on base things don’t exactly improve, as despite his rank and the more accepting attitude of Captain Taylor, both Taylor and his superior Colonel Nivens (Trey Wilson) are unhappy with the decision to appoint a black officer to investigate a crime. Taylor believes that the locals will not charge a white man for the murder on Davenport’s say so, while Nivens would be happy to just let the whole incident slide. And having met both men, Davenport then finds himself segregated from them and the other white officers and billeted on his own in an empty barracks, where a racist greeting has been painted on a bathroom mirror.

The story of what led up to Waters’ murder unfolds in a series of flashbacks as stories told to Davenport in the course of his investigation into the crime. It’s through these that we discover that far from being the beloved old sarge of legend, Waters was often a humourless disciplinarian whose strictness and intolerance bordered on the fascistic and who really had it in for popular recruit C.J. Memphis (Larry Riley). Despite this, the older and previously demoted Private Wilkie (Art Evans), whom the other soldiers rib for having no ass to kiss after Waters is killed, has largely positive things to say about the sergeant, while Private First Class Peterson (Denzel Washington) admits up front to liking nothing about him. It’s left to Davenport’s assigned driver, Private Ellis (Robert Townsend, the nearest the film comes to having a comedy relief), to reveal that two white officers were previously questioned about the crime but not charged, information that was deliberately omitted from the case file given to Davenport.

As the investigation progresses, it seems clear that racial prejudice played a major role in the sergeant’s death, but not always in the expected ways. Few will be surprised, for instance, that the two questioned white officers, Lieutenant Byrd (Wings Hauser) and Captain Wilcox (Scott Paulin), turn out to be contemptible racists who freely admit to physically assaulting Waters, but I was a certainly caught out by the contempt that Waters expresses for the members of his own race whom he believes perpetuate a damaging stereotype. Sometimes harm is inflicted almost subconsciously, as when Captain Taylor lifts the spirits of his men by warmly congratulating them on a baseball team win, then casually cuts C.J. off in the middle of an enthusiastically told story, and by doing so gives the impression that he’s not really interested in what a man he was being chummy with just a few seconds earlier has to say.

The performances, as ever with Jewison, are first-rate across the board. As Davenport, Howard E. Rollins Jr. is suitably imposing, his determination to see this assignment through doing convincing battle with his frustration at the blocks that are repeatedly put in his way. Adolph Caesar makes for a suitably acerbic Sergeant Waters, a relentless and humourless taskmaster whose spiteful targeting of C.J. and willingness to fight dirty to teach Petersen a lesson makes him easy to dislike, while the roots of his own prejudice are revealed in a riveting, single-shot monologue growled out to an uneasy Wilkie one night in a bar. As Captain Taylor, Dennis Lipscomb walks a very nice line between genuine sympathy for the men in his company and the societal conditioning that keeps him from regarding them as equals, a lingering prejudice that is gradually chipped away by Davenport’s presence. A strong supporting cast and the freedom given for the actors to improvise creates a convincing sense of camaraderie within the company, which includes early roles for some familiar faces, including actor, writer and director Robert Townsend (Hollywood Shuffle, The Five Heartbeats), Art Evans (Die Hard 2, Fright Night), David Harris (who made a memorable movie debut as Cochise in The Warriors) and David Alan Grier, whose 100+ subsequent film and TV credits include The Player, Jumanji and the more recent The Big Sick. And yes, that’s acclaimed singer Patti LaBelle as barroom songstress Big Mary. But oozing star quality from every pore even at this early stage of his career is Denzel Washington, who makes for an instantly charismatic Private Petersen in a role that allows him to really flex his acting muscles, which he does with such authority and control that despite being only his second feature film role, feels more like a guest appearance from a long-established and experienced performer.

The screenplay was adapted by Charles Fuller from his stage production, A Soldier’s Play, which was first performed by the Negro Ensemble Company, in which Adolph Caesar, Denzel Washington and Larry Riley originated the roles they went on to play in the film and Private Henson was played by an as-yet undiscovered Samuel L. Jackson. It seems important that such a tale was written from a black perspective, but it’s a sobering reflection on unchanging times that despite the play winning the Pulitzer Prize and a respected (white) director at the helm, the executives at Warner Brothers took one look at the script they had agreed to commission and declined to fund a film with a primarily black cast. Even when Columbia agreed to make it, it took Jewison’s willingness to work for nothing to convince them to do so, and even then everyone had to work at minimum pay (or scale, as it is known) to bring the film in on a $5 million budget. The very fact that A Soldier’s Story got made at all is thus worthy of note, but that it makes for such compelling viewing is very much down to the talent and commitment of those involved it is production. And at a time when a black-centric film like Moonlight can win the Academy Award for Best Film and entries in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series are on many of the year’s Best Film lists, it’s easy to forget that not so long ago such projects were regarded by American studios as box-office poison, convinced that the white audience they still saw as their key demographic would not turn out to see them. In that respect, A Soldier’s Story is not just a grippingly told drama that was a showcase for emerging and long-established talent, but an important stepping stone in the development of mainstream black American cinema.

I’m in slightly tricky territory with this one, as it’s the first film I’ve reviewed on my new 4K OLED TV, whose black levels are deeper than any you’ll find on an LCD or plasma screen and whose settings I’m still in the process of optimising, though I am just about there now. Sourced from a Sony 2K remaster, supervised by Rita Belda, this picture on this 1.85:1 1080p transfer looks terrific here, with a very fine level of crisply rendered detail and well-balanced contrast that really shines in daylight exteriors but also doesn’t punish shadow detail in more dimly-lit interiors. And yes, those black levels are unwaveringly solid throughout. The film’s earthy, khaki-influenced colour scheme is nicely reproduced, with skin tones that look natural when the light level allows and blue skies that really pop. A fine film grain is visible and the picture is spotless and rigidly stable in frame.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack has also been remastered and is in excellent shape, with a solid dynamic range, very clear dialogue, music and effects, and some distinct separation, something particularly evident in scenes involving activity and crowds.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Norman Jewison

A most welcome audio commentary from the always-engaging Norman Jewison, who provides plenty of sometimes revealing background detail on the production and the social situation in which the film is set. The racial prejudice in America at the time is discussed, particularly as it relates to the film, as is the fact that the military practiced a form of apartheid by segregating black troops and even their officers from their white counterparts. Jewison talks about shooting on actual locations, the film’s flashback structure, the problems of getting it into production, the actors, his intention to balance the drama with some character humour, the critical response, and much more. I’ll admit that I was previously unaware that Herbie Hancock’s score was not formally composed but improvised by Hancock and his collaborators as they watched the film, or that then Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton was a big supporter of the film and was instrumental in securing the National Guardsmen used in the final parade sequence. A really enjoyable and educational listen.

The DP/30 Interview with Norman Jewison (68:37)

An extensive interview with director Norman Jewson, conducted in 2010 for the YouTube channel DP/30: The Oral History of Hollywood, that collectively cover the director’s entire film career, much in the manner of the celebrated interview with Billy Wilder by Hellmuth Karasek and Volker Schlöndorff titled Billy, How Did You Do It? (which is available as a belting extra on Eureka’s Blu-ray of The Lost Weekend). The interview is divided into three parts, which can be watched individually or as a single programme, although the latter option still contains the opening titles and closing credits for each episode.

In Part One: Tea with Hitchcock (22:32), Jewison reveals how Tony Curtis prompted his move from directing television to features and talks about each of the films he made from 40 Pounds of Trouble in 1962 to The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming in 1966. He remembers being initially typecast as a director of frothy comedies and cites the 1965 The Cincinnati Kid as the film that changed the direction of his career. The tea with Hitchcock of the title saw him unable to discuss films and filmmaking as he had hoped as Hitch was only interested in the latest gossip about actors. He also provides an indicator of the Cold War attitude of the time when, after being invited to visit Moscow on the back of the success of The Russians Are Coming the Russians Are Coming, he was refused re-entry to America and described as “unacceptable.”

Part Two: The Timing Was Right (24:23) kicks off with Jewison chasing the job of directing In the Heat of the Night (1967), where he tells a neat story of how a chance meeting with Robert Kennedy saw the famed senator predict the film would be an important one. After this, Jewison continues to discuss each of his subsequent films, from The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) to Best Friends (1982), with particular focus on Fiddler on the Roof (1971), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) and Rollerball (1975). There are interesting comments and stories about each, including the fact that Burt Reynolds (on Best Friends) remains the only actor who took a swing at him during the production of a movie.

Part Three: Capturing Reality (21:41) kicks off with A Soldier’s Story and covers the remainder of Jewison’s catalogue right up to the 2003 The Statement. He has very positive things to say about Cher, whom he pursued for Moonstruck (1987), but saves his highest praise for Denzel Washington in The Hurricane (1999), whom he remembers working harder on that film than any other actor he’d worked with. He concludes by noting with a smile that whatever film he makes, he’s always anti-something. In all, this is a terrific extra that should send all film fans scurrying to the DP/30 channel for more quality content.

March to Freedom (15:03)

A 1999 featurette produced by Columbia Tristar Home Video, possibly to accompany an earlier DVD release of this film, that takes a look back at the roles played by black servicemen in World War 2 and specifically the prejudicial attitudes they faced. This is built around interviews with three notable black veterans. Roger C Terry was a rare black Air Force officer who defied the segregation rules of the day by entering the white-only officer’s mess and was charged with a capital crime as a result. Robert Routh joined the Navy to learn a trade but, along with other black recruits, was given the dangerous task of unloading ammunition from ships and was blinded in a disaster that killed more black servicemen than any other incident in the war. Vernon Baker led an almost impossible mission and won the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions, but the full extent of his heroism was covered up at the time and only revealed 50 years later, when he was belatedly awarded the Medal of Honour. An impressively eye-opening piece that could easily be expanded on and one of whose most telling comments is delivered early by A Soldier’s Story screenwriter Charles Fuller when he says, “When black people are called upon it’s because so many white lives have been lost.”

Theatrical Trailer (1:17)

A nicely suggestive trailer that technically has a couple of spoilers that you’ll likely only see as such if you watch this immediately before the film itself. So it’s probably best not to.

Image Gallery

32 screens of promotional stills plus two posters for the film.

Booklet

Opening, as ever, with the credits for the film, this 36-page booklet really gets going with a welcome and educational introduction to writer Charles Fuller, A Soldier’s Play and Jewison’s film adaptation by Molefi Kete Asante, Professor and Chair of the Department of Africology and African American Studies at Temple University, Philadelphia, and the author of The Dramatic Genius of Charles Fuller: An African American Playwright. Up next is an extract from Norman Jewison’s 2004 autobiography This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me, in which he recalls seeing A Soldier’s Play and first meeting Charles Fuller (who, it turns out, was a fan of In the Heat of the Night) and the process of getting the film adaptation financed and into production. This is well worth a read as it includes a few details not found in the other extras on this disc. Next are extracts from an interview with ace cinematographer Russell Boyd (Picnic at Hanging Rock, Gallipoli, The Year of Living Dangerously) from American Cinematographer, in which he talks about his work on A Soldier’s Story, which unsurprisingly includes a few technical details about the equipment used. Bringing up the rear are extracts from three contemporary critical reviews, two of which have holes to pick with the film that you are free to disagree with.

A film that helped to open the gate for modern mainstream black cinema, though it would be a few more years before Hollywood would get on board with the idea that a film didn’t need a cast of primarily white characters to become a success. Smartly written, well made and compellingly performed, A Soldier’s Story is a too-rarely talked about work in the career of an often undervalued and socially committed filmmaker. It looks damned fine on Indicator’s Blu-ray, and the special features, though not huge in number, are excellent. Warmly recommended.

|