| |

|

| |

"These were guys who came to Hollywood with two dreams: to either be a rock n roll star or make monsters for the movies. There was nothing else possible for them. It was a certain breed of character and Screaming Mad George was part of that group. I liked him immediately because he was so artistic and so surreal." |

|

Director, Brian Yuzna |

I hope you understand from that quote that Screaming Mad George did not go on to forge a career in music. Thank the movie gods for that. If you're going to be famous as a monster maker in Hollywood, then his choice of project was exemplary. Society's main recognizable theme – The Eton Boating Song (with such rowing-specific contortion lyrics like 'with your bodies between your knees') – seems not only apt in terms of the physical elasticity on display in Brian Yuzna's wonderfully bizarre movie but also nails the colours and politics of the filmmakers firmly to the mast. Eton is one of the most exclusive English public schools (remember, perversely, we call private schools, 'public' over here, go figure). It's known by knee jerk liberals like me as the breeding ground or indeed the compost of the elite, the place where the privileged shoots, the darling buds of maybe are prepared for power and so naturally we are not well disposed to this concept and in David Cameron's case, not well disposed at all to the results of this particular secondary education either. Eton paves the way to Oxford or Cambridge. I'm not against paying for a service, even a private education but I am a firm believer that the majority of the ruling elite should not be sifted from the same mulch. It's irony indeed that the school was founded by Henry VI in the 15th century as a charitable enterprise to provide free education to seventy poor boys who were earmarked for Cambridge. A lot can happen in five hundred and seventy five years. Eton has congealed into a two syllable exhalation of wealth and privilege to those without means and to those with families able to afford it, it's simply 'school'. To send a child to Eton for a single year minus the trimmings costs £34,000, that's £7,000 more than the average Briton earns in a year. But hey, Eton turns out Prime Ministers so it must be worth the expense, right? Or is that just me rounding up a virulently nasty, circular logic? I'll leave the class divide to be suitably castigated by my fellow reviewer.

Right now it's time to appreciate a perverse imagination from the days when computers simply computed numbers and processed words, and didn't spew out 'wow' special effects considerably undercut by the general knowledge that it's just a load of people with number crunching power doing shed loads of underpaid overtime. Have mouse, will render. Screaming Mad George took the concept of physical union and consummation, made them horribly literal and introduced another meaning to a word that always used to (before Society that is) denote a comfortable Reverend Wilbert Awdry, Thomas The Tank Engine vibe… Not anymore. Shunting is for consenting (and non-consenting) adults and ambitious teens able to find a way in to the body, a hole to violate, a weakness to push into, limbs and torso to disrupt. In so many ways, Screaming Mad George challenged the make up – special effect divide and turned it (ahem) inside out.

Billy Whitney seems to have it all. His parents are rich, he lives in a Beverly Hills mansion and as a jock, he's popular in school and on the verge of becoming class president. He's also in therapy with a deep-seated unease regarding how he doesn't fit within his own family. He muses that he might be adopted but the answer to his concerns is slowly revealed to him by the behaviour of his own kin. And it's an answer he's not about to easily believe. There are lots of ways Society conforms to a small budget 80s fantasy conspiracy picture. The hero is likeable, credible (up against some pretty stiff competition, credibility-wise); the building shocks are evenly and pleasingly spaced. We're never given enough information to see the bigger picture until the astounding finale and the score by Mark Ryder and Phil Davies feature what were then ubiquitous synth strings dialing up the tension. Despite that musical nod to budgetary frugality, the sound design is particularly good for a film of this age and ambition (we'll forgive the stock 'splash' sound effect at 37' 33"). With one or two exceptions, everyone except the hero is creepy in one way or another. And you just know that the hero's 'normal' friend who is right about the conspiracy being hidden behind upper middle class curtains, is not destined for a happy ending. Yes, these are the 'normal' elements of a horror film that promises something, something perverse, something almost alien. What we get is something that could not have been anticipated, something new, dare I say fresh. And this is why it stays in the mind for so long. The big reveals don't infiltrate your mind in quite the same way as Giger's alien designs do. This is neon body horror, not Freudian creatures of the shadows. Society's monsters are all too believable but there is a surfeit, almost a glut of wit attached to the surreality that again to my mind seems extremely original. I will never forget the images served up by director Yuzna and his talented special effects crew but neither, I hope, did I miss the point. Class war has never been so delightfully disgusting.

| |

Oh how we all get richer

Playing the rolling game

Only the poor get poorer

We feed off them all the same

Then we'll all sing together

To society we'll be true

Then we'll all sing together

Society waits for you |

The re-written but oh-so-relevant second

verse lyrics of the Eton Boat Song |

I can't actually remember my first viewing of Brian Yuzna's glorious politically satirical horror film Society, but I'm certain it was on VHS tape rather than on the big screen. This was how those of us out in the sticks discovered a lot of what later went on to become cult cinema back in the late 80s and early 90s. I even bought a well worn copy from the local video shop when they were selling off their old stock and ran parts of it it enough times to render the scenes in question almost unwatchable.

Odd though it may seem, however, I distinctly recall the first review I read of the film, one written (and indeed read) some years after its cinema release and posted on an American review site in response to the then new Anchor Bay DVD. I remember it largely because I was such a fan of the film and this review was so hostile. And I mean really hostile. What struck me and stayed with me was the intensity of the reviewer's hated for the film. So venomous was his attack that his review had next to no critical perspective, and it quickly became clear that he was taking this very personally. Long before I reached the end of the article I was aware that the writer probably did not hail from a working class background. Everything about what he had written, and especially the way it was written, suggested that he came from money, or more specifically what is sometimes referred to as 'old money', that privileged portion of American society that likes to believe it was born to rule. Yuzna's brilliantly twisted assault on this supposedly classless society's self-appointed 'ruling class' had clearly pressed on a nerve. If anything, this further increased my already substantial admiration for the film.

It's this misconception that America is devoid of the class divisions that continue to blight Britain that Yuzna himself blamed for the film's failure to connect with an audience on its home soil. A little curiously this seems to persist to this day, with a strangely high number of American on-line reviews and comments expressing bemusement at the film's strangeness and failing to pick up on its social satire at all. Yet on its initial UK release it was warmly embraced by critics and the viewing public alike, or at least those able to stomach its surrealistic horrorshow climax. For viewers on this side of the pond, the film's satirical subtext was plainly evident and struck a particular chord with those who had watched the already substantial divisions in society widen to obscene proportions under the then incumbent Conservative government. To us, it wasn't just the remodelled lyrics of the title song that clicked, it was the choice of song itself, representative as it was of the over-privileged public school educated elite, those whose futures were already mapped and whose contempt for what they perceived as the lower orders was so great that they saw them as little more than disposable plebs.

Oh how times change. Five years after returning to power as part of a coalition government and armed with a majority that will allow then to stampede through the rights of anyone they deem as being unworthy, the public school multi-millionaires are back in power, and even as I write are laying out plans to consolidate their position and make it almost impossible to remove them from office. And with a government that even current Justice Secretary and ludicrous Pob lookalike Michael Gove once famously complained had a "preposterous" number of old Etonians, the film's retooled take on the Eton Boat Song feels more pertinent that ever.* Listening to this particular, wonderfully arranged take on the song again, it played less like a parody and more like a musical rendition of current government policy.

So what was it, exactly, that so angered that aforementioned reviewer and prompted him to vent such personal bile? Well it's simple really. While on the surface a tale dark secrets in high society, the film dares to suggest that the aristocracy are not just distanced from the rest of us by money and privilege, but are an altogether different species, feeding off the so-called lower orders in more than just a figurative sense. The message is clear – society's self-styled elite are incestuous, parasitic monsters hiding behind a front of smiling respectability. This, of course, is what many of us have always suspected, but is hardly typical subtext for an American movie, even an independent genre work such as this.

That this subtext initially failed to register with the local audience seems retrospectively odd given that there are clear similarities here to the paranoia-driven alien invasion movies of the 1950s. In those films, peeling back the surface of normality would often reveal a monstrous conspiracy, while previously familiar faces could turn out to be creatures from another world. Interesting, then, that an audience willing to swallow the idea that ordinary folk could be taken over or replaced by aliens (or subtextually, communists) would baulk at the suggestion that their lords and masters could be monsters in human form.

In this respect Society is a natural companion piece to the previous year's They Live,** John Carpenter's incisive, inventive response to the horror of Reaganomics. In that film those in positions of power were revealed to be alien invaders, shrewd monsters who had effectively brainwashed the general populace into a state of blind passivity using subliminal messages hidden in consumerist products and advertising material. Both films signal that something's not quite right from an early stage, but where They Live builds a sense of science fiction-based foreboding, Society plays with the look and tropes of a high school teen movie, aided by Rick Fichter's sunny Californian cinematography and the lead player casting of Billy Warlock, a familiar face from TV soap Days of Our Lives and about to make his name as a regular on Baywatch. Thematically it's also very much in teen movie territory, in Bill's angst about his feelings of familial dislocation, his early dealings with preppie bully Ted Ferguson (Ben Meyerson), and his fractious relationship with girlfriend Shauna (Heidi Kozak). There's even dangled female temptation in the form of the beautiful Clarissa (a seriously alluring Devin DeVasquez), who on their first encounter squirts sun cream in Bill's face like a porn movie reverse cum-shot. Did we mention that this is not like other horror films?

The build-up, like that of They Live, is peppered with hints of the scale (if not the nature) of apocalyptic events to come, and you'd have to be a surrealistic psychic to predict where the story eventually takes us. Obviously the surprise factor is neutered on subsequent viewings, but there's still tremendous fun to be had spotting just how many sometimes coded pointers there are to the climactic revelation. And while I'm not about to ruin things for first timers by explaining just what the term 'shunting' means in this context, I will second my fellow reviewer's appreciation of the practical effects and gooey puppetry work of Japanese 'surrealistic makeup designer and creator' Screaming Mad George and his crew, which has a wonderfully yucky and tactile physicality that CGI has still yet to convincingly deliver. And in a lively and committed supporting cast, actor Tim Bartell's suffering in a particularly memorable shunting sequence is convincing enough to temporarily punch a hole in the surrealistic fun and allow the horror of what is happening to really register.

Society is a true original, a one-of-a-kind horror work that I fell in love with on the first viewing and take off the shelf every couple of years to revisit, always with a degree of twisted delight. It remains one of my all-time favourite political horror films, one that gets the balance between satire, horror and black comedy absolutely right, and whose social critique feels even more pertinent than ever. It is, after all, worth remembering the tag-line that Yuzna originally wanted to appear on the posters, one that proclaimed boldly that 'This is a true story'. Absolutely.

There's a sense that I could cut and paste my comments here from almost any one of Arrow's more recent Blu-ray releases of low budget horror films of the 70s and 80s. Like many of these films, I first came to Society via its VHS incarnation and thus first got to know it in the wrong aspect ratio and with its fine detail muddied. In that respect, its later appearance on DVD was a big step up – the picture was framed in its theatrical ratio of 1.85:1, the colours were brighter and we could finally see the effects in all of their glory. But this new Blu-ray release from Arrow leaves even the DVD editions standing. Looking as pristine as any decently lit and shot 35mm film should, its richly rendered colours make daylight exteriors pop and lend a deliciously hellish quality to the glowing red tint that washes over the climactic shunt. The contrast is sublimely pitched with beefy black levels but little if any loss of shadow detail, and the crispness of the image belies the film's low budget indie origins (though if I'm being honest that's down in part to the still strong memories of that VHS encounter – back in the day, that's how we tended to think all low budget horror looked). As you would hope, there are next to no dust spots, no trace of damage, and the image sits rock solid in frame. Lovely. The framing is 1.78:1, a now common but only slight shift from the original.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo track is also in fine shape, its clarity and fidelity most evident in the dialogue and the splendidly gooey sound effects.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also on offer.

Commentary

Given that the only extra feature on Anchor Bay's 2002 US DVD release was an enthralling commentary by director Brian Yuzna, I fully expected to see that reproduced here. Yet while we do indeed have a Brian Yuzna commentary, it's a brand spanking new one hosted by Arrow extras regular David Gregory (he also directed most of the other special features on this release). And against my expectations, there's surprisingly little crossover with the Anchor Bay commentary – it's almost as if Gregory had given that a good listen and was determined to cover ground not explored in detail there. As with the previous commentary, Yuzna proves a most engaging raconteur and responds to some of Gregory's questions in considerable detail, revealing information about the film, its making and his own film career that was new to me. I was intrigued to learn, for instance, that the climactic shunting sequence was influenced in part the 1932 Michael Curtiz film Doctor X and the Dali painting The Great Masturbator, and the camera placement was shaped in part by Polanski's work on Rosemary's Baby. It's all great stuff, though my favourite moment comes when Yuzna pauses during the shunting sequence and then says, "I've lost my train of thought – it looks so much fun I just want to join in."

Governor of Society (16:52)

This interview with director Brian Yuzna does revisit some of the ground covered in the commentary, but tends to develop it or cover it from a slightly different angle, and there's still enough new stuff here to make it well worth your time. Yuzna discusses how the project came to him, its similarity to one he was developing with Dan O'Bannon called 'The Men' (which sounds fascinating) that unfortunately fell through, and his influences and main intentions for the film. He has an amusing theory about guys who become special effects makeup artists (which Camus quotes an alternative version of at the top of this review), is still surprised by the scathing review that appeared in Variety, and amusingly says of his approach to storytelling, "I never reject something because it doesn't make sense."

Masters of the Hunt (22:22)

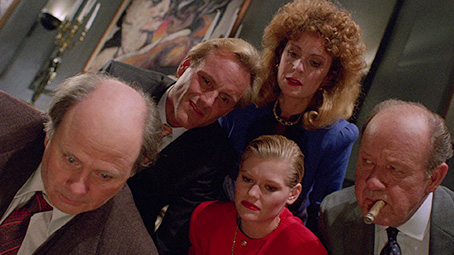

Actors Billy Warlock, Devin DeVasquez, Ben Meyerson and Tim Bartell recall their experience on what for all four of them was their first big feature role. Each outlines how they came to the project (or how it came to them) and how they got past their initial apprehension about the content of the climactic scene, memories of the filming of which prompts a few amused smiles – Tim Bartell in particular has plenty to say about this. Devin DeVasquez contradicts Brian Yuzna's commentary by assuring us that she was not at all comfortable doing the sex scene, and Billy Zane remembers attending the London premiere as "the only time I experienced the paparazzi thing" and "the best time of my life."

Champion of the Shunt (20:39)

Surrealistic makeup designer and creator Screaming Mad George tells us how he came up with his distinctive name, looks back at how and why he made the move from painting to film, and talks in some detail about his work on Society. Chipping in are 'surrealistic makeup lab technicians' (basically, George's assistants on the film) Nick Benson and Dave Grasso, and the info provided by all three on creating and operating the large sculptured puppets employed in the climax is usefully illustrated by behind-the-scenes stills.

Brian Yuzna Q&A (38:34)

Recorded at the Celluloid Screams Horror Film Festival or 25th October 2014, this post-screening Q&A with director Brian Yuzna retreads some of the ground already covered elsewhere, but Yuzna himself is so engaging and his stories so interesting that few will have cause for complaint. There's also a good deal of material unique to this extra, including a few details of his own politically fired youth and a fascinating breakdown of the setting for a possible sequel. Shot with two cameras in less than ideal lighting conditions, it's still in surprisingly good shape, but the sound – although clear enough – is at the mercy of the room acoustics, and some intermittent fiddling with one of the cameras does produce some very audible clunks on what sounds like a built-in mic.

Brian Yuzna – Society Premiere (1:56)

Brian Yuzna in conversation backstage at the Society world premiere at the Scala cinema in London (hoorah!) – it's only two minutes long and the video is low band and the sound a little raspy, but his comments on the importance of the horror genre are absolutely on the nose. Short, yes, but a most worthwhile inclusion.

Theatrical Trailer (2:08)

Not a bad sell, and it's interesting to see how the distributor tackled the problem of promoting a film whose special effects climax is its most famous and marketable feature without actually giving too much away.

Screaming Mad George Music Video (6:09)

A video made by Screaming Mad George for his own song Persecution Mania that's as much a showcase for his surrealistic art, effects and animation skills as it is for his music. Which, in its sub-Marilyn Manson way, I rather enjoyed. The video's not bad either.

Also included is a seductively produced Booklet, which includes a typically fine essay on the film by FrightFest maestro Alan Jones, some rather tasty stills (which might prove spoilers for first-timers), details of the transfer, credits for the film and repros of the poster.

This may well have changed on the release disc (or been more openly added to the special features menu), but if you highlight the Screaming Mad George music video and press the right cursor button on your remote, you get the following:

Boy in the Box (4:01)

A surrealistic short made by Screaming Mad George – the credits suggest he did just about everything on it – under the rules of his self-styled 'Psycho-Fiction' horror sub-genre. Its imagery is striking (the heads of family members are replaced with everything from light bulbs to pots of flowers), its pace frenetic, its dialogue constructed from seemingly random words, and its meanings will likely require several viewings to unpick. Which turns out to be the point, as outlined in the Psycho-Fiction manifesto that scrolls up at the film's conclusion.

One of our all-time favourite political horror films in a sublime dual format package, the gorgeous transfer backed up by a superb collection of extras. Even the packaging is lovely, so much so that despite having the film and the extras on a review disc, I've already ordered the retail version. Arrow can't seem to do anything wrong at the moment. Highly recommended.

Some elements of the above review have been adapted from our previous review of the Anchor Bay DVD.

* British composers Phil Davis and Mark Ryder were not the only ones to find satirical potential in this particular and, some have suggested, rather homoerotic song. Consider these equally pertinent lyrics written for (and we can presume by) Rory Bremner, John Bird and John Fortune for a closing sketch on their show in the lead-up to the 2010 general election:

Jolly boating weather

Vote for us if you please

You’re not so clever

You can’t afford the fees

So we’ll all stick together

With the rest of you on your knees

So we’ll all stick together

With the rest of you on your knees

** Interestingly, on the commentary track here Yuzna himself draws cultural parallels with two other late 80s cult favourites, Michael Lehmann Heathers and Bob Balaban’s superb but too-rarely seen Parents.

|