|

I’ve always been a bit surprised by Hollywood’s love affair with the English legend of Robin Hood, given that one of the things he is most well-known for is something that corporate America openly despises. Hood famously stole from the rich to feed the poor, the sort of redistribution of wealth that conservatives the world over deplore and are bribed by big business to vehemently oppose. It’s a timely tale for these troubled times. As we enter a cost of living crisis that is set to plunge millions into poverty while billionaires untainted by social conscience continue to expand their wealth, whatever the human cost, I can’t help thinking that a modern-day incarnation of Robin Hood would very quickly become the folk hero of legend. If ever there was a time when a modern day Robin Hood was needed, its right bloody now, preferably running the country. Instead we’ve been gifted a dopey stand-in for the Sheriff of Nottingham.

For Hollywood, the attraction of the tale was always the popular image of the little guy taking a stand against evil overlords and seemingly impossible odds, a grounded superhero story first coined long before superheroes were even a twinkle in the eye of comic book writers. And of course, Robin Hood has the instant appeal of being an already widely recognised and thus highly commercial brand name. The story offers opportunities aplenty for combat-based action, and features characters that viewers will at the very least be aware of even before they lay down their cash to watch the movie adaptation in question. We know Robin will meet, verbally spar with but ultimately romance Maid Marian, and we expect him to enlist the services of a big strong fellow named Little John (because he’s big, geddit?), and that he’ll recruit a rotund monk named Friar Tuck (so named because he likes to eat – who wrote this stuff?). Ballads recounting their adventures will be sung by the annoyingly musical Alan-a-Dale,* and we can expect to meet a skilled swordsman named Will Scarlet and a young fighter named Much, the Miller’s Son. The group they form hides out in the dense woodland of Sherwood Forest and remain loyal to King Richard, who’s off fighting in the Crusades, an ignoble religious endeavour that I’d happily have seen fail. Their nemesis is the Sheriff of Nottingham, who in some versions of the story is working directly for evil Prince John, who has enlisted the Sheriff’s assistance to usurp the King. Often, the Sheriff is shown to be oppressing the local populace and forcing them to pay ruinous taxes, not to provide decent public services or to help the less fortunate, but to line the pockets of the ruling elite. Sound familiar?

Despite the enduring nature of this story and its continuing relevance as a revolutionary socialist parable, any new film built around these characters is going to have to deal with a couple of issues. The first is that most will by now be familiar with the story and its characters, and will probably have already watched at least one screen adaptation already. Filmgoers my age will have seen a good many more than that. This means that every time we watch a new take on the story, we start subconsciously start ticking off the characters and by-then familiar story beats as they appear. The second issue is the insanely high bar that was set by directors Michael Curtiz and William Keighley and leading man Errol Flynn back in 1938 with The Adventures of Robin Hood. If you’re planning to adapt this story for film, that’s always going to be the first point of comparison, and if you fancy going up against such a rousingly entertaining and artistically pitch-perfect adventure tale, the best of Sherwood Forest luck to you.

It’s a challenge that was magnified for Hammer when they began work on the 1960 The Sword of Sherwood Forest, as the film was following on from 143 episodes of a TV series – one also titled The Adventures of Robin Hood – that you’d think would have explored every possible variation of the famous tale, leaving Hammer with little wriggle room for what is essentially a big screen spin-off. For contemporary fans of the series, this would not have been a problem, but if you’re coming to the film from a modern perspective without at least handful of episodes from the series under your belt, you may have questions about a storyline that treats the legend more as a jumping-off point. I’m not old enough to have seen the series even as a kid, though was keenly aware of its earworm of a theme tune, which was later hilariously repurposed by the Monty Python team for a song to accompany the activities of lupin thief Dennis Moore. I’d also somehow never seen either of the films in this set before, so approached them as someone who has seen a good many of the other film adaptations, but is also very familiar with the legend that inspired them.

And so to the films...

| SWORD OF SHERWOOD FOREST (1960) |

|

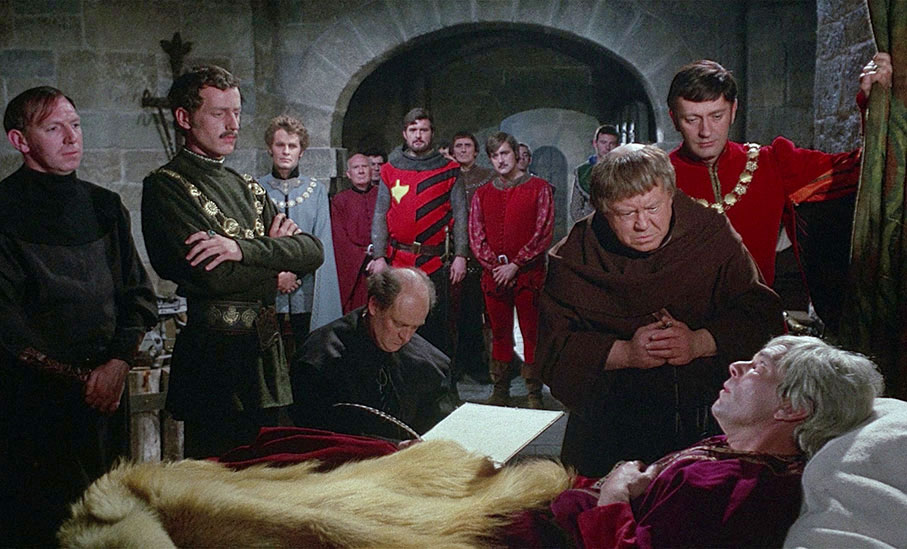

When Sword of Sherwood Forest hit British and American cinemas, for a sizeable portion of the contemporary audience, Devon-born actor Richard Greene was Robin Hood. By this point, he had played him 143 times over the course of five years in an internationally popular British television show, one whose writing staff included several blacklisted American screenwriters. There seems little doubt that Sword of Sherwood Forest was made by Hammer to cash in on the success of this series, going into production just as the fourth and final season came to an end. Visually, it differentiated itself from the black-and-white, 4:3 framed TV show by being shot in scope and in lush Eastmancolour, and it even broke with Hammer’s fondness for shooting in and around Bray Studios in Berkshire by being filmed primarily on location on the Powerscourt Estate in County Wicklow in Ireland. Hammer’s star director Terence Fisher was brought in to helm it, studio favourite Peter Cushing was cast as the Sheriff of Nottingham, and the script was the work of Alan Hackney, who had also written three episodes of the TV series and was making a name for himself as a screenwriter on sharp comedies like Private’s Progress and Two-Way Stretch.

The film almost literally begins at a gallop. A horseback rider (an uncredited Desmond Llewelyn, later to play Q in the early James Bond movies) has been stopped by a Norman patrol under the command of an unnamed Lieutenant (Edwin Richfield), and is identified as the man they looking for by an amulet he carries in his purse. Aware that he’s been rumbled, the man grabs the amulet and flees, rapidly pursued on horseback by the Lieutenant and his men. He’s hit in the back by a crossbow bolt, but keeps riding anyway, and when his pursuers try to follow him into Sherwood Forest, they are driven back by a series of dissuading arrows fired by Robin from a nearby treetop. Robin orders Little John (Nigel Green) and his companion to take the seriously wounded man to their forest camp. He remains unconscious until the following morning, when he gasps out a few desperate but cryptic words of warning before passing out and ultimately expiring from his injuries. Robin takes the amulet from the stranger’s hand, and in a bit of magical thinking surmises that this is what the Sheriff was after. He then pays a visit to Friar Tuck (Niall MacGinnis), where he encounters a band of men led by Edward, the Earl of Newark (Richard Pasco), who is curiously keen to test Robin’s archery skills. After noticing that Edward wears a similar amulet to the one he took from the fatally injured man, Robin plays along, unaware that he has stumbled across a plot to assassinate Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter (Jack Gwillim).

Given that this film followed on from the TV series, it’s no surprise that there is no origin story here. In Sword of Sherwood Forest, Robin and his Merry Men have clearly been outlaws for some time, which kicks against the sometimes heard claim that by this point Green was too old for the role. Come on, he was only five years younger when the series began, and I’ve not heard the same complaint made about his portrayal there. All the more surprising, then, that the film elects to have Robin and Marian (Sarah Branch) meeting for the first time, a part of the origin story that theoretically should have played out long before this point. It was doubtless believed that a romantic subplot was needed to offset all the manly action and intrigue, and we can’t have someone as pure-hearted as Robin moonlighting with someone other than Marian.

While Sword of Sherwood Forest does have the look and pacing of a feature film, its “this week’s adventure” storyline does sometimes give it the feel of an extended episode of the TV series, one that is aware that we know the principal characters by name – and the lead one by sight – but keen to give us a story that the series has not yet explored. Which is all well and fine if you’ve been watching the series, to which this will probably feel like a natural extension, but whether this works as a plot for a stand-alone feature is another thing entirely. Working in its favour is series regular cinematographer Ken Hodges’ scope colour cinematography, the lush Ireland locations, a sprightly score by Alun Hoddinott, and the casting of Hammer favourite Peter Cushing as the Sheriff of Nottingham. If you accept that the film is looking to put a new spin on an oft-told story, the plot also has a few unexpected turns. The first of these occurs early when Marian invites Robin to meet her at an inn, where the Sheriff of Nottingham is waiting not to ambush him but to strike a deal for the return of the man that his men were pursuing. His traditional role as the story’s chief villain is also gradually and unexpectedly usurped by Edward, whose head thug Lord Melton is played by an uncredited and peculiarly accented Oliver Reed, and a sense of escalating intrigue is created by the tests that Edward subjects Robin’s archery skills to. The simple fact that he doesn’t execute them perfectly each time somehow makes his archery feel a little more grounded in reality.

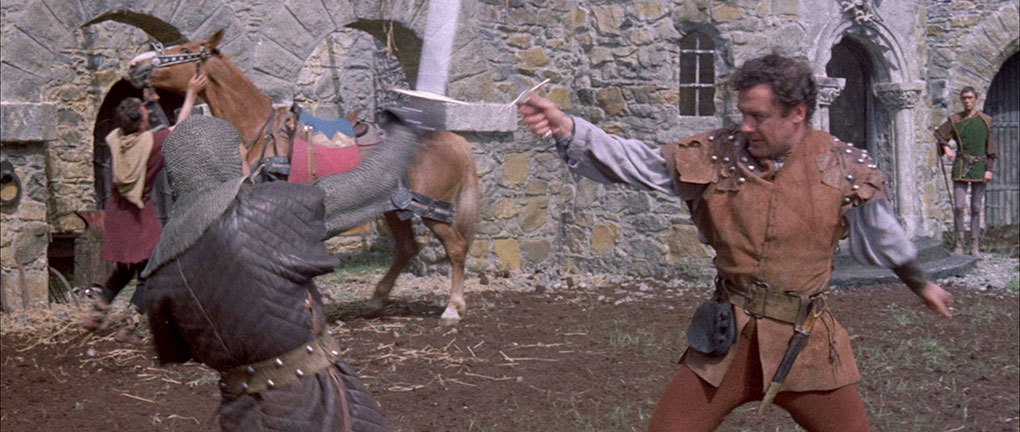

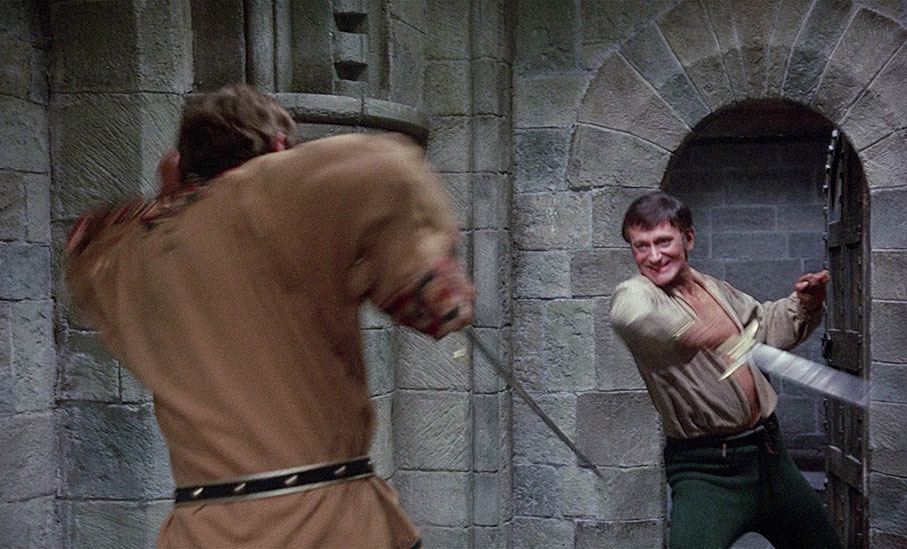

Kicking against this a little is a lack of grandeur to a story that still feels like one originally drafted for an episode of the TV show, despite a genuinely surprising late-film twist that would have never have found its way into that series. In what is a rare move for me, I’m also going to have to disagree with Barry Forshaw and Kim Newman, who on their commentary claim that the combat sequences are well staged. I’m not so convinced. Putting aside the considerable shadow cast by the skilful swordplay in The Adventures of Robin Hood, the physical conflict here sometimes has the feel of fights that are in the later stages of rehearsal, lacking as they do the speed, force and total commitment of realistic swordplay. This is especially true of a climactic battle inside a convent, where the lead fighters intermittently pause and stare at each other for a second or two after executing a move, as if trying to momentarily recall what the next one is before pulling it off. It’s still energetically staged and rather fun, but does lack a real sense of urgency and genuine danger.

If you’re not worried by this and accept the episode-of-the-week storyline, Sword of Sherwood Forest is a professionally handled and rather enjoyable family-friendly adventure tale. That cast is certainly a draw, with Niall MacGinnis as an uncharacteristically low-key Friar Tuck (this does, however, see his comedy moments fall a little flat), Richard Pasco as a most impressively shifty Earl of Newark, and the ever-reliable Nigel Green a suitably imposing Little John. The film also conforms to the unspoken rule that the moral inferiority of the bad guys is reflected in their choice of weapons, with the just-point-and-fire nature of the crossbows wielded by the Normans lacking the elegance and required skill of the Sherwood men’s longbows (the same rule dictates that guns are only used by evil men in samurai movies). It looks good, bounces along at the sort of cheerful pace that was a hallmark of director Fisher’s work, and has a climax that could be read as quietly mocking of standard notions of religious sanctity and piety. It’s also the only big screen outing for Robin Hood in which the title character was played an actor who for a whole generation was the TV incarnation of the character, which alone makes this as a work of some note. The real surprise, however, is that despite the film’s box-office success, there was never a sequel. Indeed, it would be several years before Hammer would have another stab at the legend…

| A CHALLENGE FOR ROBIN HOOD (1967) |

|

Having dispensed with the necessity for a Robin Hood origin story back in 1960, seven years later Hammer chose to deliver one after all with A Challenge for Robin Hood. Now I should start by noting that there is no definitive origin story for a man who was not a historical figure but the product of ballads and folk tales, so storytellers and filmmakers have a free reign here. The favourite take has always been that Robin was a nobleman of some means who had his property seized by the Sheriff of Nottingham, and various stories and movies cast him as Robin of Loxley (or Locksley, depending on the source), Robin Earl of Loxley, or even Robert of Loxley. In A Challenge for Robin Hood, he’s Robin de Courtenay, the cousin of Roger (Peter Blythe) and Henry (Eric Woofe) de Courtenay, whose elderly father Sir John (William Squire) is a wealthy and powerful Norman nobleman and landowner who holds the devoted Robin in higher regard than either of his duplicitous sons.

The film wastes no time in establishing Roger as an appalling little shit when he kills a local peasant in front of his young son Stephen (John Gugolka) for aiming his bow at a royal deer, which was an act of desperation on the man’s part to provide some food for himself and his hungry family. Roger, it turns out, is happy for them to eat grass like the other animals of the forest. If that wasn’t enough, the awful bastard then demands that Stephen pull the arrow (which was fired from a crossbow, of course) from his murdered father’s back and return it to him. The task eventually falls to Roger’s loyal squire Wallace (John Harvey), and on being handed back the arrow, Roger calmly wipes the man’s blood from it and returns it to his quiver. Two minutes in and I already detest him, and he’s not finished yet. When the distraught Stephen launches an arrow in Roger’s direction, the loyally obedient Wallace is ordered to return the projectile in kind, which he does by telling Stephen to run for his life and then chasing him through the dense woodland firing crossbow arrows at him in a Sherwood twist on The Most Dangerous Game. Fortunately for Stephen, he runs into Robin, who is outraged by the actions of Roger and his squire and sends the unrepentant Wallace on his way.

It's when Robin accompanies Stephen to the murder site that we learn that Stephen’s late father was a Saxon nobleman named Sir Brian Fitzwarren whose property and possessions were seized by the Normans. It’s here that the first threads connecting this Robin Hood-to-be to the characters of legend start to become slyly visible. You’ll need to keep your ears open, or you’ll miss Stephen’s anguished cry, “They took my sister Marian,” while those who know the legend will doubtless pick up on the similarity of the family name Fitzwarren to Fitzwalter, the surname first given to Maid Marian in the play The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon by playwright Anthony Munday in 1598 (it was also Marian’s surname in Sword of Sherwood Forest). I’m a fan of these low-key character introductions, which continue when Robin returns to the family castle. Here Sir John is helped down to dinner by a jovial Friar (James Hayter), who is left for us to identify as Tuck, with the film only confirming him as so a few scenes later, when we also learn that Will Scarlet (Douglas Mitchell) and Little John (Leon Greene) are two of Sir John’s loyal retainers.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, though you might not think so if you were measuring the above against the running time of the film, as it moves at a lick and crams a lot into these early scenes, both in what it shows and what it subtly suggests. Take the sequence where Tuck helps the ageing and infirm Sir John down the castle staircase to the dining table, cheering him along with friendly quips about the slow speed at which they are moving. When the chortling Sir John says, “You’ll be the death of me, Friar,” Tuck throws a quick glance towards Roger and responds, “Not I, Sir John.” These turn out to be prophetic words, as just seconds earlier Roger quietly confessed to his brother that he is itching for his father to die so that he and Henry can inherit his title and estate. It’s a wish not shared by the wily Henry, primarily because he doesn’t trust Roger one iota and is not sure where he’ll stand with him once their father has gone.

When Robin arrives and confronts Roger about the killing of Brian Fitzwarren, Roger initially responds by blaming the shooting on Wallace, then backtracks and angrily claims that the man had it coming because he was aiming an arrow at one of the King’s deer. Again, this has a contemporary ring. He commits an appalling act, tells lies in an effort to cover it up, then when the truth is exposed he U-turns and blames it on somebody else – this guy is Tory prime minister in the making. Sir John is horrified, especially when he learns the name of the victim, and Robin angrily berates Roger for actions that the arrogant bastard refuses to accept were unjust, firmly establishing that the problem here is not the Normans per se, but this particular Norman. A few seconds later, the foundations are laid for another interesting twist on the legend when Lady Marian Fitzwarren (Jenny Till) and her retinue arrive seeking shelter for the night. When greeted by Robin, the woman in question certainly fits the profile of the Marian of legend, but Robin is unexpectedly not attracted to her, but to her humble handmaid Mary (Gay Hamilton), whom Marian then curtly dismisses as “just a maid-servant.” What, exactly, is going on here?

I should note that by this point we’re just 11 minutes into a 96 minute movie and we’re thus still effectively in the setup portion of the story, but things start developing rapidly from here. At dinner, Sir John proposes a toast to King Richard, and when Marian reveals that he has been captured, the heart attack that Roger has been praying for lands Sir John on his death bed and dictating his will. He leaves money to his retainers and to Friar Tuck, and decrees that his castle, his estate and the rest of his fortune be divided equally between Roger, Henry and Robin. Unsurprisingly, Roger is outraged that his “ill-bred upstart” of a cousin should get a share, and immediately after his father expires, he tears up the will and burns it. It's a move that infuriates Robin but prompts Henry to point out that there were plenty of witnesses to Sir John’s final words, something that Roger seems curiously unconcerned by. It’s then that we get another of the film’s telling exchanges when Henry says to Robin, “Myself, I bear you no grudge,” to which Robin responds, “Thank you, Henry. We’ve never been friends nor have we been enemies, so… let it remain so.” Chance would be a fine thing. Minutes later, Roger lures Henry back to the room in which Sir John is now lying in state and kills him using Robin’s dagger in order to frame his cousin for the murder. The whole thing is secretly witnessed by Tuck, who sneaks out to warn Robin, and escapes the castle with him when Roger brings guards to Robin's door to arrest him. The following day, the two escapees are attacked by soldiers and their lives are saved by the lethal archery skills of Alan-a-Dale (Eric Flynn) and the same group of woodsmen who earlier blamed Robin for the Fitzwarren murder and were only prevented from killing him by young Stephen’s pleas. Although initially suspicious, once they learn that Robin is also now an outlaw they accept him into their ranks, and after he demonstrates his considerable skills with bow and staff and proposes measures to protect the group from the Sheriff’s men, they elect him as their leader.

Having had a lukewarm response to Sword of Sherwood Forest, I went into A Challenge of Robin Hood fully expecting to have my patience tried, but instead found myself hooked from an early stage. It’s always a matter of personal taste, of course, but for me this proved to be a more engaging Robin Hood movie all round, in its robust structure and its incident-busy story, in its thoughtful dialogue, in its unwaveringly brisk pacing, and its more convincingly staged and altogether tougher action. Indeed, as noted more than once in the special features, this may have been originally intended as a children’s film, but the Hammer that gave us some of the most memorable horror works of the 1960s refuses to take a back seat here. As a result, we have in Roger as dastardly and corrupt a villain as you’ll find in any Robin Hood movie, and fights whose energy and brutality made me wonder if director C.M. Pennington-Richards quietly told both parties that their opponent had said nasty things about their respective mothers and then let the cameras roll. The Merry Men are a convincingly hardy-looking bunch, the Sheriff of Nottingham (John Arnatt) is a lot wiser to the danger Robin represents than he’s often portrayed to be (he’s also a sleazy would-be rapist, just in case you start admiring him), and we even get a brief origin story for the outlaws’ fabled wearing of Lincoln green.

Not everything is quite as robust. A warning system that involves firing arrows some distance to alert the next in line would frankly risk the injury or death of the recipient if just slightly misjudged, and more than once Robin and his men win a fight because the Norman soldiers stumble about like untrained buffoons. The film takes its biggest chance of all at a county fair, where Robin and his men make their escape under the cover of what is effectively a custard pie fight, a sequence that risks tipping the drama into farce but that is well integrated enough into the narrative not to feel completely absurd. I’ll bet the younger audience of the day loved that scene. And sacrilegious though this may read to some, but I personally preferred Barrie Ingham’s commanding interpretation of Robin Hood to Richard Greene's more easy-going take in Sword of Sherwood Forest. I certainly liked Greene, but would more readily join up with Ingham and follow him into battle. There’s another shrewd piece of casting in James Hayter as Friar Tuck, a role he was nigh-on perfect for and had already played back in 1952 in Walt Disney’s The Story of Robin Hood. And if you’re going to have a bit of comedy relief, you could certainly do worse than hand it to Alfie Bass as the pie merchant whose goods are later put to such diversionary use.

Against my expectations, I really enjoyed A Challenge for Robin Hood. All of the key elements really click here, and while it was apparently targeted at the younger market, there’s a strong sense that the filmmakers wanted to make a movie that would also appeal to an adult audience. We’re still in the realms of a fantasy take on the legend here – grittily realistic this is not – but as such films go, for me A Challenge for Robin Hood is in the top tier of cinematic takes on what remains one of our most enduring folk legends.

Both films have been transferred to Blu-ray from high definition remasters from what looks like different sources (Sword of Sherwood Forest has the Columbia logo, whereas A Challenge for Robin Hood comes from Studiocanal), and I’m guessing they have also been restored at some point, as both are clean of dirt and damage and sit rock solidly in frame. They also look good. Sword of Sherwood Forest was shot on Eastmancolour stock in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio in what the opening titles claim is ‘Megascope’, and the results are handsome, with the greenery of the Irish countryside and the brighter colours of costumes really shining here. The contrast is nicely balanced and the manner in which the film was lit and photographed ensures that the solid black levels do not swallow any of the surrounding picture information. Surprisingly, as the more recent film, A Challenge for Robin Hood is framed 1.66:1, but the image quality here is even better than on the earlier film. Detail is really well defined, the DeLuxe colour is handsomely rendered, and the contrast grading is absolutely spot on. A fine film grain is visible on both transfers.

Both films feature Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtracks, and both are clear within the expected limitations of a dynamic range that was typical of the day, and both are free of any obvious signs of damage or wear. The music scores in particular are pleasingly reproduced.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available for both films, and for the special feature, Robin Hood Junior.

THE SWORD OF SHERWOOD FOREST

Audio Commentary with Barry Forshaw and Kim Newman

Writers and commentary maestros Barry Forshaw and Kim Newman tackle what they suggest at one point is the best of Hammer’s Robin Hood adaptations – going to have to disagree with you on that one, chaps. It matters not, as these two collect and store film facts like the world’s most committed philatelist collects stamps, and their commentaries together are always a rich and entertaining cornucopia of enthusiastically delivered information and opinion. Areas covered here include The Adventures of Robin Hood TV series and its blacklisted writers, how the film differentiates itself from its TV forebear, Richard Greene’s Robin, the Ireland locations, the interior production design, director Terence Fisher, the actors and performances, and much more. Newman suggests the sequence where the Sheriff threatens to kill Martin is one of Cushing’s best, and also makes a persuasive case for the notion that Cushing was a late addition to the cast, a theory that is then undermined by the background research done by Jonathan Rigby in his interview below. A most enjoyable companion to the film.

Interview with Terence Fisher (75:50)

A 1967 audio-only interview with Terence Fisher, conducted for the purpose of research rather than broadcast, hence the up-front warning about the audio quality, which does occasionally render questions hard to clearly hear, but is otherwise perfectly tolerable given the considerable value of the content. The identity of the interviewees is never confirmed (I initially presumed they were writer-researchers, but a later comment suggests that they may also have been filmmakers), but they pose some useful questions that prompt frank responses from Fisher. It takes a while to really get going, as the three men spend the first ten minutes hotly debating Roman Polanski’s then recently released Repulsion, a film that Fisher has considerable issues with the content of, despite his admiration for its director. Areas then explored include the notion of horror cinema as art, directing actors whose vision of the film differs from your own, the most difficult aspects of filmmaking, the preparation required when working with performers for the first time, the lack of opportunity in the British film industry for creative talent, and plenty more. Fisher admits to preferring the term fantasy to horror when applied to his films, and rather pleasingly for this particular fan looks back at the 1958 Dracula as his finest achievement, in part due to what a pleasure it was to make and how smoothly it all came together.

The BEHP Interview with Sidney Cole (79:40)

An audio-only British Entertainment History Project interview with Sword of Sherwood Forest producer and former editor Sidney Cole, conducted in 1987 by Alan Lawson, Arthur Graham and Rodney Giesler. As is usually the way with BEHP interviews, Cole begins with his early life and how he got into the film industry, then traces his career chronologically, starting with his early days as an assistant editor to Thorold Dickinson, then moving on to his work as an editor, associate producer, and eventually producer. The journey is peppered with enthralling anecdotes and the useful reminder that Cole edited one of the finest British films of the 40s when he worked with Alberto Cavalcanti on Went the Day Well?, a film he holds in extremely high regard. Absolutely with you there, sir. There are further interesting tales of working on Dead of Night and Scott of the Antarctic, and Cole does discuss The Adventures of Robin Hood and the hiring of blacklisted American writers, but does not even mention the feature film spin-off that this special feature accompanies. Fascinating stuff, nonetheless, and the audio quality is very good here.

Play it Again: Richard Greene (22:59)

An episode from the Tyne Tees television series Play it Again, the format which had host Tony Bilbow – now there’s a TV face from my younger days – interview a celebrity about his or her career, which was broken up by favourite film clips selected by the guest in question. Greene proves to be a most congenial interviewee, sharing memories of working with John Ford and his friendship with Humphrey Bogart, as well as discussing some key points in his career, including the then risky decision to move from movies into television for The Adventures of Robin Hood. Surprisingly – and this is really unusual for a disc special feature due to rights issues – all of the film clips chosen by Greene are included.

Dennis Lotis: Merry Memories (3:52)

A brief chat with South Africa-born singer and occasional actor Dennis Lotis, who plays Alan-a-Dale, or Alan A’Dale as he appears in the cast list. Several memories of the shoot are fleetingly touched on, with his most detailed recollection being of miming the playing of a mandolin.

Pauline Wise: All in a Quiver (6:15)

After quietly cursing whoever it was at Indicator who usurped my first choice of title for this review, I settled down for an engaging chat with the film’s continuity supervisor, Pauline Wise. She looks back at how living close to Bray Studios saw her trained as a script supervisor for Hammer, and how she was unexpectedly sent to Ireland to work on The Sword of Sherwood Forest after Richard Greene refused to work another day with her predecessor, only to discover that her primary task once there was to keep track of the number of arrows in Robin Hood’s quiver.

Jonathan Rigby: Riding Through the Glen (28:48)

English Gothic author and Hammer devotee Jonathan Rigby delves into the background of the making of Sword of Sherwood Forest, as well as providing information on the Powers Court Estate location in Ireland, the actors, and even the creation of the film’s attractive opening titles. He quotes from the minutes of Hammer board meetings, which confirm not only that Peter Cushing was cast even before production began, but that he was originally supposed to be partnered with Christopher Lee. Now there’s an intriguing prospect. He nicely sums the film up but describing it as “a school holidays movie that still holds up today.”

A Hero’s Fanfare: Huckvale on Hoddinott (22:40)

Our favourite music score analyst returns to outline the work and career of celebrated Welsh composer Alun Hoddinott, before examining and deconstructing his score for Sword of Sherwood Forest. As someone with the musical ability of a rusty stapler, I always find this sort of thing fascinating, and Huckvale is such a clear communicator that I always feel I have learned something new.

Isolated Music and Effects Track

As the title says, but I should note that if you switch between this and the regular soundtrack when music is playing, there is a deceptive sense that the music is a little richer here, but this is largely down to it playing at full volume instead of being intermittently lowered for dialogue and other effects.

Theatrical Trailer (1:53)

If the urgent American narrator and the “New excitement! New thrills!” graphics are anything to go by, this just has to be a trailer for the film’s Stateside release. Makes it look exciting, though.

Image Gallery

63 screens featuring promotional stills, posed portraits, behind-the scenes shots, outrageously coloured lobby cards (plus a few less garish but still tinted German ones), French press book pages, and international posters.

A CHALLENGE FOR ROBIN HOOD

Audio Commentary with Kevin Lyons and Jonathan Rigby

Here the commentary duties fall to Jonathan Rigby and Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Films and Television website editor Kevin Lyons, who admit from the start that they’re rather fond of this film, and upgrade this as the film concludes by suggesting that it belongs on the pantheon of Robin Hood movies. They do note that it’s something of a schizophrenic film, being aimed at kids but peppered with Hammer violence and brutality, and provide information on its origins, its actors, its risky stunt work, screenwriter Peter Bryan, and director C.M. Pennington-Richards. They also praise its brisk pacing and the fact that it belies its modest budget. There’s plenty more to get your teeth into here, all of it well worth a listen.

The John Player Lecture: The Hammer Forum (61:08)

Chaired by John Russell Taylor at the National Film Theatre in London in 1971, this on-stage discussion was arranged as part of a BFI season celebrating the work of Hammer Studios, and includes contributions from Michael Carreras, Peter Cushing, Terence Fisher, James Needs, Anthony Nelson-Keys and Jimmy Sangster, names that should all be familiar to Hammer aficionados. It has to be said that Taylor is a little bit sniffy about some the critical acclaim that Hammer films had by then attracted, but his attempts to prompt a similar response from his guests are instead met with wry surprise that it’s taken so long for these movies to be recognised for the fine works they are. A lot of ground is covered in the hour that this runs for (it plays as a second commentary track to the film), and it reinforces the feeling that working for Hammer was akin to being part of a large and dedicated family, and that a key thing that distinguished the studio’s films was the sincerity of those who made and acted in them. As is often the way with such archival features, this was originally taped for record purposes only and the audio quality is thus imperfect, something that only becomes an issue with the audience questions, almost none of which I was able to clearly make out. It’s still very entertaining, though my favourite bit comes late in the audience questions when Peter Cushing gets to his feet and says in his wonderfully dry manner, “I haven’t got really anything to say, but may I stand up? These seats are dreadful.”

The BEHP Interview with C M Pennington-Richards (96:28)

A 1990 interview with A Challenge for Robin Hood director Cyril Montague Pennington-Richards, often credited as C M Pennington-Richards, or on this film simply as Pennington Richards. I’ll admit his was a name I was not previously familiar with, and after listening to the details of his remarkable career, I was left feeling more than a little remiss on this score, particularly when I learned that he photographed Humphrey Jennings' extraordinary wartime drama-documentary Fires Were Started. The usual BEHP format is adhered to here, with Pennington-Richards discussing his career chronologically, first as a lighting cameraman of note and then as a director, primarily in TV, with the amount of time spent discussing any specific title dictated by how many stories he has to relate about its making. It’s an enthralling listen littered with engaging anecdotes – I certainly warmed to his description of TV commercials as “a whole industry built on rubbish,” and was oddly delighted by the revelation that when he retired from directing in his late 60s, he became a motorcycle courier and loved it so much he started his own courier company.

John Gugolka: An Excuse for Action (11:13)

John Gugolka, who plays young Stephen in A Challenge for Robin Hood, recalls being cast in the film and shares his memories of playing a role in which he modestly claims he was “not very exceptional at all” (he’s actually rather good). He clearly enjoyed the experience, even if he seems to have taken playing Stephen somewhat in his stride, and does feel the scene in which he coins the name Robin Hood is a bit corny. I wasn’t going to say anything…

Kim Newman: Sherwood on Screen (24:44)

Here Kim Newman takes a trip through the history of the portrayal of Robin Hood on film. He kicks off with how the various takes on the legend were formed into the version that effectively shaped almost all future takes on the tale, and along the way discusses one intriguing sounding production starring Patrick Troughton, of which I was previously unaware and that has now sadly been lost. A solid overview that should give at least a couple of titles to add to your watchlist.

Songs from the Hood: Huckvale on Hughes (11:23)

David Huckvale is back again, this time to tell us a little about composer Gary Hughes, and to deconstruct key themes in his score for A Challenge for Robin Hood. As before, this is fascinating and educational stuff for us musically talentless movie watchers.

Theatrical Trailer (1:57)

The narration may be typically over-dramatic, but as a plug for the film’s action credentials, it does the job, despite a couple of minor spoilers.

Image Gallery

A whopping 125 screens featuring promotional stills (the best of which are of excellent quality), posed cast and character portraits, lobby cards, pages from the German, French and British press books, and international posters.

Robin Hood Junior (1975) (60:45)

A 1975 production for the Children’s Film Foundation that is not a tale of Robin Hood’s younger days but one that takes place in the world of Robin Hood when Robin was active elsewhere. Here the Normans are once again oppressing the citizens of a Saxon village, whose defiant children take their inspiration from Robin’s rebellious actions over in Nottingham. The kid’s leader is also named Robin – hence the title – and if you listen carefully and you’ll pick up that his band includes stand-ins for Little John and Will Scarlet. We even have a teenage Maid Marion (Mandy Tulloch), who is differentiated from her adult namesake by swapping the third vowel in her name from an a to an o. The bad guy is Marion’s uncle, the Baron de Malherbe (Maurice Kaufmann), who learns that his brother, Gilbert, Earl of Shelbourne – Marion’s father and the Lord of Locksley Castle, in which the Baron resides – has been stricken by a deadly illness while fighting in the Crusades. The Baron doesn’t seem too upset by this – he was the one behind Gilbert's poisoning, after all – and is set to inherit his castle and its lands if he can just get Gilbert’s rightful heir, the young Lady Marion, to sign them over to him. She’s having none of it, and when the Baron elects to starve her into cooperating, her good friend Jugge (Tony Aitken), the castle jester, helps her to escape, and a short while later she (almost literally) falls in with Robin and his friends.

For the most part, Robin Hood Junior sticks to the CFF template by making the children smarter and more resourceful than the scheming adults, and you know from an early stage that they will ultimately triumph without sustaining a single serious injury between them. When it comes to CFF films, this was never a handicap, as their primary audience was school-aged kids like me who watched these films as part of a Saturday Morning Pictures programme. What still impresses all these years later is how good the film looks, and I’m not just talking about the handsome restoration work done here. Period-set CFF films were rare due to the extra cost this incurred, but the filmmakers here secured the use of Allington Castle in Maidstone as their prime location, and the services of Up the Junction and Cathy Come Home cameraman Tony Imi, whose colour cinematography and naturalistic lighting give the film the feel of one whose budget was higher than it doubtless was.

A little more jolting to my childhood memories was the fact that Robin is played by a teenage Keith Chegwin, someone those of my age will primarily remember as one of the most irritating TV personalities of his day on annoying kids shows like The Multi-Coloured Swap Shop and Cheggers Plays Pop. He wasn’t much of an actor and tended to get by on ebullience and energy, and that serves him well enough here, at least if you’re able to ignore the fact that you’re watching Cheggers dressed up as Robin Hood. The other child actors are serviceable without making much of an impression either way, and really are outshone here by the adults, with Maurice Kaufmann playing to the gallery at times as the evil Baron, and Fawlty Towers’ Andrew Sachs gooning it up entertainingly as a cowardly Friar who agrees to assist this band of determined child outlaws.

As a kid who went through his own Robin Hood phase and even made crappy bows and arrows from tree branches and string, I would have lapped this up, and despite a few elements that my adult self has a little more trouble digesting, I still thought it a great deal of fun. Even Cheggers ends up being tolerable here. Full marks to Indicator for including this. But wait, there’s more…

Audio Commentary on Robin Hood Junior with Vic Pratt

Film researcher and CFF enthusiast Vic Pratt is back with another of his entertaining and informative commentaries, though this one is primarily focussed on Cheggers, whose career and personality Pratt examines in far more detail than any other aspect of the film. Maybe it’s me, but something about the tone of his delivery and his choice of words suggests that while he has a grudging respect for the sort of things that Chegwin was rather good at, Pratt liked him as a TV personality about as much as I did in my youth. And did I detect a similar level of disdain for Noel Edmonds? You’ll get no quarrel with me on that one. He clearly likes the film a great deal overall, though, and responds to one particularly negative review that dismisses it as rubbish by suggesting that at least it’s cheerful and charming rubbish.

Also included with the release version is a Limited Edition Exclusive 80-Page Book with a new essay by Frank Collins, an article on Richard Greene, archival materials, contemporary reviews, and film credits, plus a Limited Edition Exclusive Poster, but these were not available for review.

Here’s the thing. Even if neither of the two films in this set were up to much, this release is so packed with top quality special features that I’d still be enthusiastically recommending it. But both films are absolutely worth a look, and the chances are at least one with tickle your quiver. I enjoyed them both, and while I far preferred A Challenge for Robin Hood, I can easily see others championing Sword of Sherwood Forest or even rating them equally highly. Either way, this is a terrific package overall and a must for Robin Hood enthusiasts and Hammer film collectors alike, so absolutely comes highly recommended.

|