|

The River was director Jean Renoir’s film in colour, made in India after a seven-year and five-feature-film sojourn in Hollywood. On the surface it’s a calm film, led by its characters rather than by a tightly-wound plot, but there are things below the surface which will snag you, and tragedy is as present as comedy.

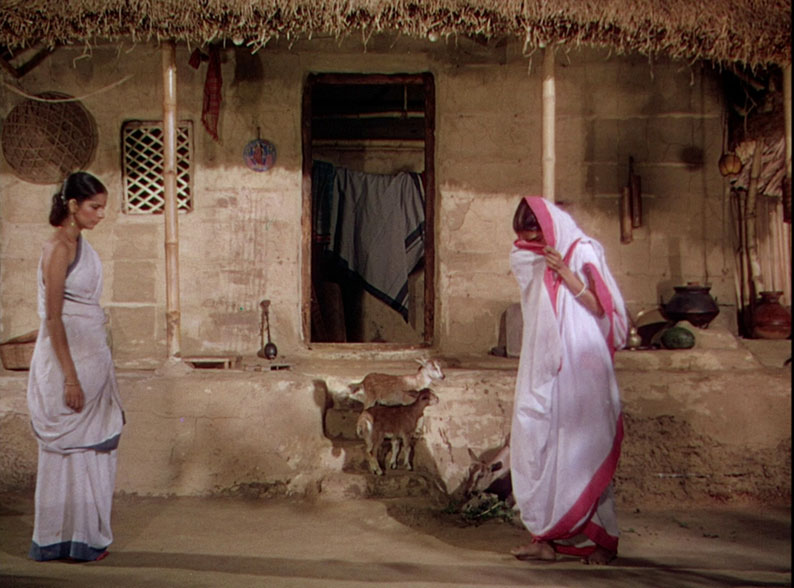

Shot in three-strip (monopack) Technicolor, The River immediately attracted notice as one of the major achievements in colour cinematography to date. In that, the obvious comparison is with a film made in 1947, also based in India and adapted from a novel by the same writer, also in Technicolor. However, the comparison ends there: great as it is, Black Narcissus was entirely studio-bound while The River was shot on location with sections of it almost documentary (shot without direct sound due to the noise of the bulky Technicolor camera). The original author famously disliked the film of Black Narcissus, but with The River she was able to cowrite the screenplay with Renoir.

Margaret Rumer Godden (1907-1998) wrote more than sixty books, novels for adults and children, non-fiction and poetry. Born in England as one of four sisters, she was brought up in what was then British India (Narayanganj, now in Bangladesh) as her father worked as a shipping company executive. Godden was a popular novelist whose works readily adapted to film or later television. She clearly had a moment in the late 1940s, as in between the films of Black Narcissus and The River, Hollywood also adapted her novel A Fugue in Time (US title Take Three Tenses) as Enchantment in 1948. Later adaptations include The Greengage Summer (filmed in 1961), In This House of Brede (made as a television movie in 1975) and her children’s novel The Diddakoi (not a title you could use nowadays) became a BBC children’s serial in 1976 under the title Kizzy, watched by me at the time. Her novels frequently centre with women or teenage girls and Black Narcissus and In This House of Brede deal with women in religious communities, and the conflicts which arise there.

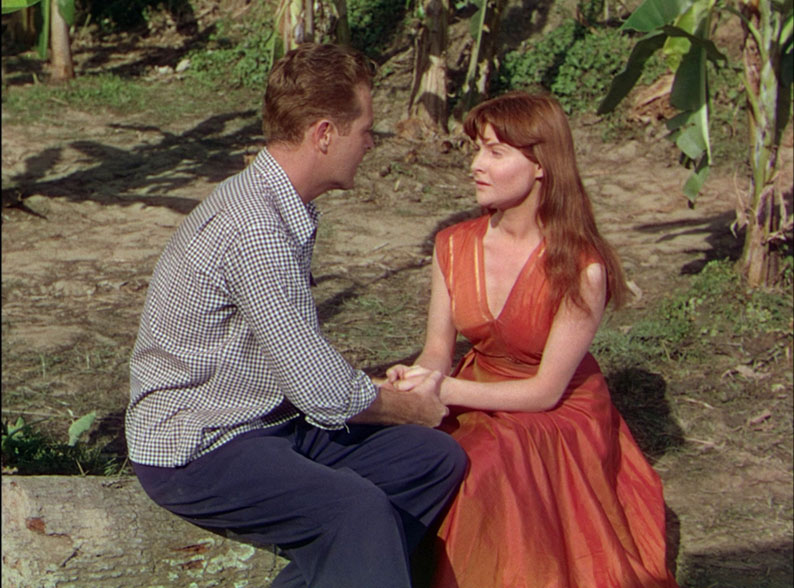

You can see the autobiographical elements in The River (the film – I’ve not read the novel). Harriet (Patricia Walters), our protagonist and narrator, is one of four sisters, but the story adds a younger brother, Bogey (Richard R. Foster). “The only male among us females”, Bogey follows his own path, often spending time with his young Indian friend Kanu. Harriet’s best friends are Valerie (Adrienne Corri) and the Anglo-Indian Melanie (Radha), all on the cusp of adolescence, and the inevitable conflicts arrive when Captain John (Thomas E. Breen), who has lost a leg due to a war injury, comes to stay. Melanie was an addition to the film, added by Godden after visiting India and noticing a decline in relations between the two peoples since she had grown up there in the teens and twenties. Melanie is the product of an interracial marriage (though we don’t see her Indian mother), which is something you can’t imagine Hollywood going anywhere near at the time and some racism directed towards her is subtly but unavoidably indicated.

Renoir had been unhappy in Hollywood, though his stay there had resulted in some fine films. He came across Godden’s novel and with producer Kenneth McEldowney in tow, went to India to shoot the film. The actors were a mixture of professionals and non-professionals, and Renoir was able to work in natural locations, something he preferred but about which he clashed with the Hollywood studios. His cinematographer was Claude Renoir, his nephew, and Satyajit Ray, four years away from his own feature debut, worked on the film as an assistant director (uncredited). The River was an arduous shoot, and the lack of processing facilities in India caused plenty of issues. Renoir had to construct the film in the editing room, with a voiceover from adult Harriet (voiced by June Hillman) having to hold much of it together, especially in the first part.

There’s no doubt that The River is a view of India through western eyes, and the film doesn’t always avoid exoticism. Yet in its unhurried pace and its open eyes to the vast and colourful landscape, it casts its spell. The river of the title is both the reason for the family’s income, and a symbol of the cycles of life, beginnings, ends and renewals. The River is a beautiful film, and was recognised as such as soon as it was released. It escaped Oscar attention, but picked up BAFTA nominations for Best British Film and Best Film from Any Source, losing in both categories to The Sound Barrier.

The River is a BFI Blu-ray release, comprising two discs both encoded for Region B only. The River and the extras relevant to it are on the first disc, while the other extras are on the second. The River itself has always had a U certificate, but the package is raised to 12 by a scene of domestic violence in India: Matri Bhumi. Around India with a Movie Camera is PG-rated.

The Blu-ray transfer is based on a restoration by the Academy Film Archive with the cooperation of the BFI and Janus films, from the original 35mm nitrate three-strip negatives held at the BFI National Archive. The Blu-ray transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.37:1. On the whole, this is an impressive transfer, with only minor issues: some speckles in places and some minor colour shifts that you do see in other three-strip Technicolor films of the time. It does look very good, and I speak as someone who has seen this film in a cinema shown in a 35mm print.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered in LPCM 2.0. There’s nothing untoward about it, with the dialogue, narration, music and sound effects clear and well-balanced. English subtitles are available for the feature and for the two items on the second disc with foreign-language narration or intertitles.

Introduction by Kumar Shahani (16:17)

“It is always great to see the work of a master, again and again in fact.” So begins Kumar Shahani’s introduction, so you can guess where he stands. He does admit that he, like many Indians, found the film a little embarrassing but has since thought again – the authenticity, he says, is being true to him/herself rather than immersion into a foreign culture and in this case Rumer Godden’s childhood. Shahani talks about Renoir’s eye for colour, which he used more for documentary purposes rather than for abstraction, as his father for example might have done.

Around The River (59:41)

An hour-long documentary made in 2008, detailing the making of the film. More than fifty years later, of course, many of the participants were no longer alive, so we hear from Jean Renoir’s son Alain, and, via archive footage, Satyajit Ray and producer Kenneth McEldowney.

Trailer (2:36)

This trailer, with an American voiceover narration, gives the definite impression that they didn’t really know how to see this film, as it’s one of those tradition-of-quality miss-at-peril-of-your-soul efforts that stops short of including actual critical quotes. It begins, “This theatre has the rare honour of presenting as a future attraction Jean Renoir’s masterpiece The River. For those of you who have been asking for something new and different in entertainment, for all of you who enjoy only the finest in motion pictures, The River is especially for you,” and continues in that vein for two and a half minutes.

Image gallery (5:04)

A self-navigating gallery of poster designs and production stills, the latter mostly in black and white.

The second disc features films which are less pertinent to The River, but deal with the larger subject of India instead. The disc begins with an advisory caption that they display attitudes of the time and are views of the country from outsiders rather than those from the culture itself. There’s in effect another such disclaimer in the booklet as well.

India: Matri Bhumi (90:13)

Roberto Rossellini made this part-fictional documentary in 1959, visiting India at the invitation of Prime Minister Nehru. Rossellini had seen The River at this point. The title translates as India: Mother Earth. The intention was to make an eleven-episode series but a series of setbacks, and objections from Indian filmmakers about this Italian interloper, so the film finished up as a ninety-minute feature, shot by the great cinematographer Aldo Tonti, in a mixture of 16mm and 35mm. None of the participants were professional actors. The final film does fall into episodes, but fewer than originally intended, beginning with elephants used to clear sections of forests. Another section shows the construction of the Hirakud dam through the eyes of Devi, a young workman. We see a local village taking part in a tiger hunt and are told the story of an old man travelling to the city with a monkey in tow.

The film premiered at Cannes with a French narration, but that version was since lost for many years. The more usual version is the one on this disc, with an Italian voiceover (English subtitles available). Only one print was made and over the years some six minutes went astray. The present restoration was carried out by the Cineteca in Bologna at the laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in somewhat yellowish colour, presented in an aspect ratio of 1.37:1

Around India with a Movie Camera (72:52)

This documentary, made in 2018 was made by the BFI in collaboration with the UK Council for British India. It’s a compilation of digitised footage dating from the earliest known shots of India on film in 1897 to material made just as the country became independent in 1947. It mixes silent footage with sound, black and white material shot by amateurs with Technicolor material with Jack Cardiff behind the camera. Inevitably, these are mainly the views of outsiders again, partly because much Indian material (for example, from royal collections) was not able to be licensed. So we have examples of singers in brownface. We also have a tiger and a lion fighting, undoubtedly not faked, though you may be glad to hear that the film cuts away before things become too graphic.

Villenour (French India: Territory of Pondicherry) (4:20)

A French-made travelogue from 1914 which is given a striking look by the use of stencil colouring.

Manufacturing Ropes and Marine Cables at Howrah, Near Calcutta (7:39)

This 1909 film, whose subject is summed up in the title (an activity we see some of in The River), is in black and white other than the title card and intertitles, which are on coloured backgrounds. Those intertitles are in German, with optional English subtitles.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet runs to thirty-six pages and is available in the first pressing only. It begins with a three-page essay by David Thompson (spoiler warning attached). If that seems shorter than many lead essays in BFI booklets, Thompson continues out of an archive with an interview with Rumer Godden conducted in 1993. Godden says that the film might not have happened as after Black Narcissus (which she thought was terrible) she instructed her agents to sell no more film rights. Not being much of a filmgoer, she had not heard of Jean Renoir when the offer came in (though she had guessed correctly that he was the son of Auguste Renoir). However, she was swayed when Renoir visited the Bengali town where Godden had grown up and visited her in Buckinghamshire and invited her to Beverly Hills to write the script. She was on set, often being an unofficial minder for the children in the cast.

Next up is Satyajit Ray, with an article, “Renoir in Calcutta”, originally published in Sequence in 1950, before the film was released. It’s a discussion in the main of how film directors often don’t fare well outside their home country and industry, and how the Hollywood system was different to the French, language obviously apart. At first Ray was disappointed that the film as originally envisaged would concentrate on the western family and have little of the actual India in it, other than being shot on location. However, changes were made to the script before the film was shot.

“Can the Indian Speak?” asks Dina Iordanova, who talks about the fact that the film, and Rossellini’s for that matter, is for all its aesthetic qualities is still a product of colonial attitudes and made with a western gaze primarily for western audiences. This is particularly the case when you consider that it was made (and is apparently set, though timescales are vague) just after India’s Partition, and Renoir had witnessed trainloads of refugees fleeing East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), but this is something you wouldn’t sense in the film itself. India: Matri Bhumi does concentrate on its Indian characters but again, they do not get a chance to speak for themselves.

The booklet (or at least the PDF copy I received for review) doesn’t contain credits for The River itself, but it does include notes on and credits for the extras, with a short essay by Tag Gallagher on India: Matri Bhumi.

Though some may find its viewpoint of its time, The River is a moving film which deserves its reputation as one of the great colour films of its time. The BFI’s two-disc Blu-ray presents it to its best advantage.

|