| |

"I've just been wanting to set a movie in Y2K for a long time. It’s a somewhat forgotten period that younger kids don’t even remember or realize just how paranoid it got. There was an entire year or two of very real, mounting fear that all things modern may come to an end. People were building shelters and stocking up. It was silly and kind of freaky at the same time. It’s the ultimate timeframe for a Potrykus movie." |

| |

Writer-director Joel Potrykus, interviewed on Split Tooth Media* |

There was a time, back in the early days of video games, when they weren’t designed to be to be completed but to just get increasingly harder as the player progressed. The sole goal when playing such games was not to finish them but beat your previous high score or those of players whom you knew only by three-character monikers on the high score table. These were cabinet-based games that you had pay to play and were designed to push you into wanting to get that bit further than you previously had and thus keep you pumping coins into the machine. And yes, I’m old enough not just to remember this trend but to have been part of it. Buy me a beer and I’ll tell you about the day that I became the first person to beat the Scramble machine located in the café on an East London Industrial Estate and loop the game right back to its beginning, all in front of the previous high score holder (who, to his credit, applauded my efforts).

Later these games and the ones that they spawned became available on early home video game consoles, and not having to pay out for each attempt to better your previous high score took the cap off the addiction factor, leaving players free to play and replay a particularly tough level until they fell asleep at the joystick. Again I’m not trying to sound judgemental but speaking from happy experience. It’s the not-too-distant memory of this that enabled the premise of director Joel Potrykus’s fourth feature Relaxer (with the impending Y2K apocalypse fast approaching, Abbie is faced with the ultimate challenge – the unbeatable level 256 on Pac-Man – and he can't get off the couch until he conquers it**) to hook me before I’d seen a frame of the film. Yet this hook – at least the video game element of it – proves to be both the driving force of the narrative and a sizeable MacGuffin, a reason to keep the lead character glued to the sofa that isn’t the real reason he stays there at all.

Okay, a little clarification is called for here. Abbie is a 20-something slacker who is crashing in his brother Cam’s small and grubby city apartment. As the film begins, he’s sitting on the couch that dominates the room dressed only in shorts and socks, playing Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater on the Nintendo 64 and attempting to trigger a glitch that flips the game world upside-down. Somewhat mysteriously, he’s also regularly chugging milk under stopwatch-timed pressure from his bossy brother. It transpires that this is the latest in a series of challenges set by Cam that Abbie has previously failed to complete, one that requires him not to move from the couch until he has consumed eight baby feeding bottles full of milk. When a last-minute rule change sees Cam pour a final beaker of liquid from a container into which a desperate Abbie has secretly urinated, the notion of even sipping it prompts Abbie to explosively vomit all of the downed milk and fail the challenge. After a heated discussion that teases information out about both brothers, Cam sets the challenge outlined in the above plot summary, then departs with a stern warning to Abbie not to move from that spot until the set task is complete. It says so much about the relationship between these two mismatched siblings that not only does Abbie do exactly as ordered, despite Cam not being present to witness any transgressions, but Cam is able to leave knowing full well that this will be the case. Although fear of retribution from Cam definitely plays its part, the driving force behind Abbie’s determination to stick to the set rules appears to be a burning desire to just once succeed at something, however absurd, and prove he’s not the loser that Cam so sharply berates him for being.

This rigid adherence to the rules creates a whole raft of problems for Abbie, who is given no time to make any preparations before the challenge is made and too hastily accepted. Rooted to the spot as he is, even getting access to the essentials becomes a task and a half. Phoning his friend Dallas to shop for supplies backfires when he is unable to cover the cost of the goods, and he ends up having to construct makeshift tools to try and open a window and collect rainwater to avoid dehydrating in the summer heat. Later, when the building’s janitor turns up to fumigate the apartment following signs of a cockroach infestation, he refuses to budge from the couch even when it is picked up and moved by the janitor and his assistant.

There is, inevitably, an absurdist element to the whole endeavour, but one that makes peculiar sense if you buy into the main premise. As the film metamorphoses almost invisibly from naturalism to something more metaphorical, decisions that make little real world sense seem logical when read for what they seem to be saying about society and the way we interact with others or choose to distance or isolate ourselves from them. A sly dig is made at our increasing obsession with the technology around which our lives increasingly revolve, which here is under threat of self-destruction at the hands of the approaching Y2K apocalypse, and if you’re young enough for that term to mean nothing to you, a quick history lesson is probably in order.

Back when computers were in their infancy, the amount of memory available for the system software was severely restricted (the first computer I owned had a whacking 48K of memory for everything, including programs, which at the time was regarded as generous), a little precious space was saved by having the year in the system clock represented by the last two characters only (this year would be 20, for example). As the decades flew by and the end of the millennium approached, it dawned on the technologically savvy that there was no way for this little piece of space-saving brilliance to tell that 1999 was going to be followed by 2000 and that it would likely reset the date to 1900 instead. So widespread was this little oversight that every computer system on which we then relied – from personal PCs to the ones running power, air traffic control, the stock markets and so on – had the potential to catastrophically fail as the millennium came to an end. Software engineers made a fortune checking and correcting company systems for what became known as the Millennium Bug, and when the predicted collapse of society failed to occur at the appointed hour, it was widely suspected that the whole thing was a monumental hoax perpetrated by coders to fleece companies out of gobs of cash (the cost of correcting the error is estimated to have cost over $300 billion). The opposing viewpoint claimed that the extensive work done to correct this potentially catastrophic glitch is what prevented the predicted disaster from occurring, despite the fact even unchecked systems continued to function without issue. In the real world, the Y2K apocalypse simply never happened and we moved on to waiting for the world to be overrun by zombies instead. In the alternative timeline in which it seems increasingly likely that Relaxer takes place, all such certainties are off the table.

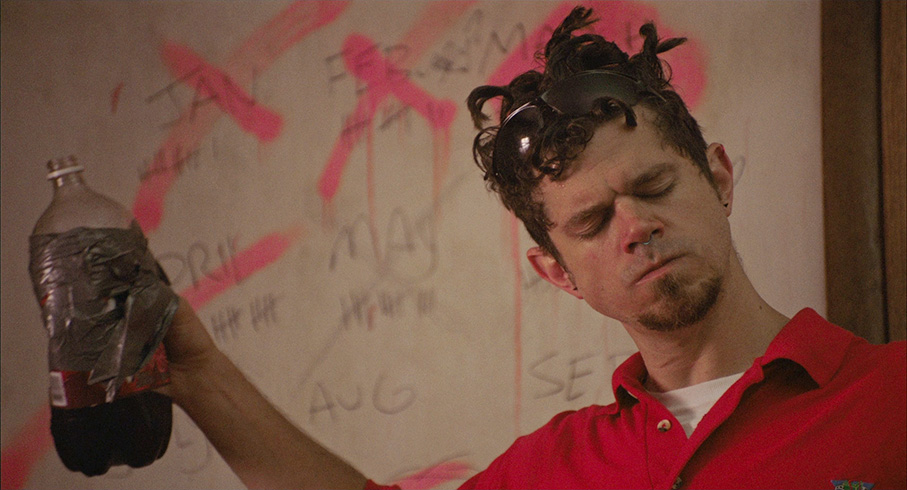

On paper at least, Relaxer shouldn’t be able to hold our attention for an hour and a half, but it absolutely does, primarily because Potrykus gets so many things right. First up is the casting. Having previously worked with lead actor Joshua Burge on two of his three previous features and his 2010 short Coyote (included on this disc) and been friends with him since childhood, he clearly knew full well that Burge had the requisite skills to often wordlessly carry a substantial portion of the film. Looking like a cross between Steve Buscemi and Buster Keaton (the Keaton haircut was a deliberate choice) and wearing an expression of nigh-on constant discomfort, Burge makes Abbie an oddly arresting screen character, one you may not fancy spending time with or imagine yourself being, but whose peculiar plight I found myself increasingly sympathising with. But he’s not alone. David Dastmalchian, a busy actor whose credits include Prisoners, Blade Runner 2049 and the upcoming Dune remake, is a convincingly intimidating ball of pent-up antagonism as Cam, while as Abbie’s not entirely sympathetic friend Dallas, Andre Hyland’s dryly witty delivery (the timing of his “This shit’s fuckin’ hypnotic” comment after staring at TV snow for longer than you’d logically wait for a VHS tape to start is priceless) makes his one-scene appearance a lively and memorable one. Later, in a sequence visually inspired by Willard’s conversations with Kurtz in Apocalypse Now but also having a whiff of Pedro Costa about it, Adina Howard really convinces as the only person who expresses real concern for Abbie’s welfare and mental wellbeing.

This all dovetails neatly into the film’s second strength, its sparky dialogue, a blend of Potrykus scripted lines and improvisations on the part of the actors, which together enliven every dialogue exchange and give pace and direction to sequences that narratively don’t go anywhere. Back story exposition, meanwhile, is so deftly incorporated into the banter that it never feels like exposition at all, with the result that the significance of Abbie’s feelings for and connection to his now absent father is something we absorb over time without having to have it explicitly spelt out. The film also benefits from Potrykus and regular cinematographer Adam J. Minnick’s use of long takes and slow camera moves, which effectively push the filmmaking into the background and create a discomfortingly tangible sense of being trapped in the room with Abbie, which the seedy hellhole feel of Mike Saunders’ production design ensures is never a remotely comfortable place to be.

Potrykus is never explicit about his subtext and there’s sometimes a sense that we’re being invited to find our own in a tale that nonetheless feels too substantial as a drama to be devoid of secondary meaning. There are also some interesting and possibly accidental links to other movies and real-world touchstones, from the titular column-squatting protagonist of Luis Buñuel’s Simon of the Desert to the isolationist existence practiced by Japanese Hikikomori. There’s also likely a whole essay waiting to be written about the unspoken events in Abbie’s past that have shaped him into the dysfunctional slacker he appears to have become and so soured his relationship with his overbearing brother. Potrykus also throws a risky curve ball by suggesting that the power over people and objects that Abbie seems to believe that his 3D glasses give him might actually be for real, producing observable effects that could also be down to handy coincidence or autosuggestion, at least until a startling climactic demonstration that may or may not all be in Abbie’s by-then isolation and temperature-addled mind. By then realism has taken a hike anyway, but in a way that works for the story and makes a kind of twisted sense, and that concludes with a to-camera gesture that I gather has had some scratching their heads but which made perfect sense to me.

Relaxer was my belated introduction to the clearly distinctive cinema of Joel Potrykus and it hooked me completely from its opening scene, an object lesson in just what you can achieve with one location, one lead actor and a small number of supporting players that will doubtless alienate as many as it delights. Wittily scripted (and improvised) by an fine cast, there is so much going on subtextually here – about social isolation, the nature of obsession, the pain of reaching high and failing, and more – that just a few hours after I watched the film I was sitting down for a second viewing to look for things I felt sure I had missed the first time around. It made me immediately want to see more of this particular filmmaker’s work – handy then, that an earlier feature and three of his short films are included in this set.

Relaxer was shot on the Arri Alexa, a popular choice on projects with the budget to stretch beyond the sort of semi-pro equipment that so many indie directors start off with. Obviously there are certain things we wouldn’t expect to see on a transfer from a digital original, such as dirt, damage and film grain, and none of those are present here. The detail is crisp and the contrast and colour have been graded to emphasise the gloomy seediness of the apartment, which does see black levels occasionally softening, but when daylight makes its way into the room the image has a considerably punchier tone. When brighter colours briefly make an appearance, as in the Pac-Man cartoon that Dallas mistakenly brings round on videotape and plays for Abbie, they are vibrantly rendered. The framing is the standard cinema widescreen ratio of 1.85:1.

The Linear PCM stereo track is very cleanly and clearly recorded and mixed, with excellent reproduction of sound effects (oh, that milk vomiting) and especially the very cool Neon Indian score.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Joel Potrykus

A welcome and enthralling commentary track from writer-director-editor Potrykus, who breaks down the process of making this low-budget feature in the hoped-for detail, with specifics on the casting, the set (which was built inside in production designer Mike Saunders’ two-car garage), the long takes and slow camera movements, the milk vomiting sequence, the set dressing and props, and more. He’s open about his influences, some of which – Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain – hadn’t occurred to me, and it’s here that I learned that the main reason Abbie looks so much like Buster Keaton (apart from sharing some of his facial features) is down to his hairstyle being modelled on Buster’s own. He has to stop at one point to take care of his infant child, which I’ve no doubt people who are not me may be rather charmed by, though quite how they’ll react to his habit of playing device-generated 80s video game-style music when he can’t think of anything to say is a different matter.

Behind the Scenes (7:05)

Unedited footage of the filming of a long, single-shot dialogue exchange and the prep for as second take. Interesting for the peek it provides at the enclosed (and clearly very warm) apartment set.

Deleted Scene (4:11)

An unnamed pizza delivery guy shows up at the apartment with his co-worker looking to have a go on the Tony Hawk game Abbie is seen playing at the start of the film, only to be rebuffed because of the Pac-Man challenge. I’m not sure whether this was a cut scene or was simply replaced by the more fleshed-out (and funnier) sequence involving Dallas, which begins with exactly the same dialogue.

Rehearsal Footage (10:00)

Director Potrykus (who throws himself into the task) takes the role of Cam for the rehearsal of a long dialogue exchange with Joshua Burge, all captured in wide shot in what I’m guessing is Potrykus’s living room.

Milk Party (9:02)

DV footage recorded by Potrykus of himself and his friends participating in a night-time challenge to drink as much milk as possible without puking, with a cash pool that everyone throws into being won by the last person to heave up the contents of their stomach. Those easily triggered by such things should be aware that there’s a LOT of for-real milk vomiting here.

Joel Potrykus Short Films and Music Video

The Ludivico Treatment (1998) (1:39)

A short film made by Potrykus on what looks like 8mm film in which experiments with stop motion pixelation are set to music that riffs on the A Clockwork Orange-inspired title.

The Ludivico Testament (1998) (4:09)

Further experimentation with stop motion pixelation that sees a young man (played by Potrykus’s brother Chuck) tormented by a telephone, a cooking pot, a blanket and a small humanoid figure, all set to an avant-grade soundtrack. The effect is pleasingly disturbing.

Coyote (2010) (24:10)

Potrykus’s first collaboration with Relaxer lead player Joshua Burge, who here plays a slacker trying to suppress his werewolf compulsions with music and drugs. Potrykus’s fondness for long-held takes is in early evidence here, notably in a heroin-cooking sequence that plays out in real time. Given the subject matter and tone, I’m guessing few will see the Bande à Part-influenced dance sequence coming.

Heavier Than Air Flying Machines: Follicle Gang (Green) (2011) (2:05)

An appropriately grungy music video for the band and song of the title.

Test Market 447b (2019) (1:46)

A gag short in which a blindfolded humanoid cow and chicken are fed snacks made from meat from their own animal group and respond to the revelation with fury, which is followed by a third test subject who reacts in a way that is probably meant to surprise but that most should see coming. Not without its charm.

Theatrical Trailer (1:54)

An intriguingly offbeat trailer with an artificially sensual, advertising-friendly female narrator who at one point breaks the fourth wall by questioning what she is being asked to read out.

David Dastmalchian Promos (1:57)

Three variations of a promo in which actor David Dastmalchian as a knife-wielding Cam aggressively challenges the viewer, in the manner of the challenges he sets Abbie, to sit and watch Relaxer, warning us of the consequences of moving from the couch or looking at our phones.

Image Gallery

A gallery of 48 behind-the-scenes stills, which you can manually advance using the remote control.

Given that this 2-disc package has been released as Relaxer instead of as a Relaxer/Buzzard double-bill, we’re invited by default to treat Buzzard as a special feature. Yet this is not an early short film by Potrykus akin to those detailed above, but the writer-director’s second feature, and it comes complete with its own solid set of extras, including a Potrykus commentary, and thus deserves to be covered in similar detail.

Here, Joshua Burge plays slacker Marty Jackitansky, who in a scene bookended by dual appearances of the main title arrives at a meeting with the manager of the bank at which he has a savings account. Marty’s open admission that he’s temping at another branch of the same bank and that he is skipping work for this meeting initially flummoxes the manager, but the man is really thrown when Marty closes his account and then asks to use the withdrawn funds to open another one that pays a fifty dollar dividend to new customers. The sequence runs for 5 minutes and 35 seconds and plays out entirely on a close-up of Marty. By the time the main title made its second appearance I was once again hooked.

Back at work, Marty is asked by his supervisor Carol (Teri Ann Nelson) to track down the new addresses of customers whose cheques for small tax refunds have bounced back as undeliverable, then mail the cheques out to the correct addresses. It says a lot about Marty that he responds by pointing out to Carol how busy he is whilst sitting at an empty desk in front of a PC that’s not even switched on. He gets onto it anyway, but during the course of a phone call to his mother that evening he learns that a cheque made out to someone else can be easily signed over to him, and despite warnings of the potential consequences from his annoying workmate Derek (played by Potrykus himself), he hoodwinks a friendly teller and pockets the cash. When the plan backfires and Carol starts looking into where the undelivered cheques have ended up, the alarmed Marty packs a few essentials and blags his way into sleeping in the basement of the house Derek shares with his father. The already fractious relationship between the two eventually sours even further, and Marty goes on the run with the stolen money and a Nintendo Power Glove he has modified by adding knives to the fingers in the manner of the handpiece worn by A Nightmare on Elm Street’s Freddie Krueger.

As a film character, Marty is another strangely compelling creation, one I found myself rooting for even as I wanted to slap seven bells of crap out of him for his selfishness, delusional lack of foresight and even simple awareness of the increasing seriousness of his situation. The duality of this response kicks in at an early stage, with any amusement at the methods he employs to wangle small but cumulatively useful sums of money out of his firm undercut by the near-certainty that sooner or later he’s going to get rumbled. That I cared at all is down in no small part to a degree of empathic recognition of Marty’s situation, of what it’s like to do a mundane office job and maybe take or do something you’re not supposed to and get so comfortable doing it that any risk you’re taking stops feeling like a risk at all. But it also stirred a few memories from my years as a workplace union rep, of cases where a simple misdemeanour quickly blew up into something more serious because instead of coming clean the person concerned unsuccessfully tried to cover their tracks with false evidence and lies, seemingly blind to the notion that a company would have the resources and motivation to investigate and expose any such infractions. It’s because of this dual-layered response, perhaps, that for all his failings Marty feels as real as any film character I’ve spent time with all year, and while his actions and attitude might frustrate, I still felt a connection to him that I found hard to break, even when the increasingly reckless nature of his actions digs a hole that only he seems unaware that he can no longer climb out of.

Joshua Burge is absolutely spot-on as Marty, getting under the skin of the character and really shining when required to carry a whole scene in long-held close-up or react to what he perceives as the unreasonable attitude of others. Surprisingly, perhaps, Potrykus’s performance as the twitchily irritating Derek never plays as the compromise move it partly was, and had I not known this was Potrykus in advance then I suspect I would have found myself researching what else this amusing actor had done. Once again, there are no weak links in the supporting cast, with even those cast in smaller roles – Alan Longstreet as a you’re-not-fooling-me gas station clerk, Rico Bruce Wade as motel manager Larry, Crystal Sparks as a startled maid – delivering performances on a par with those of the leads. I’ll give a special nod here to comedic actor Joe Anderson as business owner Craig Kowalczyk, who in scene in which he asks Marty into his office to keep him talking until the authorities arrive (whether they do or don’t I’ll leave for you to discover) is so convincingly naturalistic in his delivery and realistic in his banter that it took me in a flash back to some of the more disreputable episodes of my own misspent youth.

Having come to Potrykus via Relaxer I was expecting to have to make a few allowances for this earlier and lower budgeted film, but despite just how much I enjoyed the headline feature, I have to admit to liking Buzzard even more. I realise that this is partly influenced by the order in which I watched the films, with Relaxer’s claustrophobic one-set confinement opened up to a wider world in Buzzard, the reverse of which is likely at the root of the disappointment with the new film expressed by a small number of fans of its predecessor. Given the strong metaphorical tone of Relaxer, what caught me out about Buzzard is how grounded it is in a reality I recognise, despite being set on a different continent to the one in which I experienced my own youthful stumbles of self-centred stupidity. Chronologically speaking, it’s a substantial first half of a terrific slacker double-bill, though given the spread of its qualities it seems a little perverse that its most celebrated aspect is an unbroken five-minute shot of the lead actor lying in bed eating spaghetti and meatballs.

Buzzard was shot on a Canon 5D Mk II DSLR, which until Panasonic and Sony released models that give it a serious run for its money, was the number one choice for independent filmmakers looking to create high quality images on a minimal budget. The results here make a mockery of the notion that they were captured on a camera costing only a whisper over $2,000, though this doesn’t take account of how good the optics on Canon’s lenses are or just how far digital technology has advanced in the 20 years since the Millennium Bug failed to crash the world. Shot entirely by natural and location light sources, the depth of field is sometimes narrow but the crucial detail is almost always sharp, while the contrast is well balanced and the colour naturalistic and rich when appropriate. As with any digitally shot feature, there’s no film grain, but also no trace of dust or damage, and while the image does have a sometimes digital feel at times, I didn’t spot any major compression artefacts. For a micro-budget feature, Buzzard looks good. The framing is 1.78:1.

The linear PCM 2.0 stereo track here is cleanly recorded and mixed, and while the dialogue is occasionally at the mercy of room acoustics, it’s always clear with a strong dynamic range, and the brief but memorable snatches of music have real punch.

Again, optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been provided.

Audio Commentary with Joel Potrykus

Although an earlier film than Relaxer, this commentary was clearly recorded after the one for that film and possibly specifically for this release, and despite Potrykus’s claim here that “sometimes in these commentaries I have nothing to say,” there’s not a substantial gap anywhere in this one and thus no 80s game music used to fill the voids. I really enjoyed the commentary on Relaxer, but for my money this one is even better, being crammed with interesting background material on the making of a film whose budget was just $10,000 and whose story saw Potrykus and shooting guerrilla style on actual locations with a DSLR camera and a minimal crew. We learn about the elements he drew from experience (he also once worked as a temp at a bank), that all the costumes were sourced from Goodwill stores (the American equivalent of charity shops), why he likes to shoot in long takes, that the movie was essentially made by six people and took a month to shoot but five years to release, and plenty more. I was particularly intrigued by his admission that because he believes that mobile phones are uncinematic, they do not exist in the world of this film. Great stuff.

Buzzard: The Rehearsal Cut (64:35)

Rehearsals of many of the key scenes, shot in a variety of locations on what looks like a range of devices, assembled into a rough cut of the film with Potrykus standing in for any absent actors. By this point almost everyone seems to have their characters and dialogue nailed down, but it’s interesting to see how each was finessed for the finished film. Includes a first stab at the exhilarating climactic street run borrowed from Leos Carax’s Mauvais sang.

Buzzard at Locarno International Film Festival (8:51)

A well shot and assembled (by Potrykus’s regular DoP Adam J. Minnick) video diary of events leading up to and immediately following the film’s international premiere at the Locarno International Film Festival in August of 2014. The film didn’t win any of the top prizes (it scored a Junior Jury Award – Special Mention), but Potrykus got to meet Dario Argento and give him a Demons t-shirt of his own making.

Behind the Scenes (7:32)

Divided into three sections, Behind the Scenes #1 (2:25), Behind the Scenes #2 (1:56) and Derek Sucks (3:10), which can be watched individually or in sequence, this slickly assembled collection of material stretches the concept of behind-the-scenes footage to include outtakes, gags and even deleted sequences. Of interest, particularly the footage of Potrykus as Derek taking fall after painful-looking fall from a speedy treadmill.

Deleted and Alternative Scenes (8:44)

Seven sequences that again can be watched individually or played as a single extra. Nothing too revelatory and one of the clips is also in the behind-the-scenes collection, but there’s more of Derek being a dick, plus a sequence in which he and Marty are playing video games and Potrykus’s improvisations cause Joshua Burge to corpse.

Hidden Buzzard (0:25)

A couple of hidden snippets of symbolism in the film are highlighted.

Theatrical Trailer (1:48)

A smartly assembled trailer for a film that’s not easy to slap marketable extracts together for. Some positive critical quotes are overlaid, one of which is read out by someone impersonating Alan Rickman. Seriously.

Festival Trailer (1:51)

A slightly more punk-slanted trailer, but one that would have got me into the cinema out of curiosity alone.

Image Gallery

46 screens of very nicely shot production stills.

Booklet

There seems to be an almost template-set format for the booklets that accompany Blu-ray releases from British independent distributors now, one that everyone (myself included) seems happy with and that new label Anti-Worlds seems set to follow. The one here certainly qualifies, with the credits for Relaxer fronting an essay on the film, rather nicely subtitled Pac-Man Delirium, The End of the Century and the Pointless Challenge of Existence, by Nathan Rabin, which proves a really smart and enjoyable analysis of the film and its themes. Next is a piece entitled Fear and Loathing in Grand Rapids: Managing Anxiety While Making Relaxer, in which Joel Potrykus explores the anxieties he suffered and how he medicated them when prepping for the most expensive shoot of his career to date. The credits for Buzzard are followed by a nicely observed new essay on the film and on the state of Michigan by Caden Mark Gardner, plus an appreciation of Potrykus and Buzzard by filmmaker Alex Ross Perry, whose own movies I’ve still yet to really warm to. Finally we have credits and very brief summaries for each of the short films included in this set.

I appreciate that there some serious holes in my viewing experience, especially in the realms of recent low-budget independent American cinema (how much of it even makes it to the UK?), but I can’t quite grasp how I’ve failed to previously see any of the four features made so far by Joel Potrykus. Not only are they right up my street, but whenever Potrykus talks about the films and filmmakers he loves and is influenced by, I tend to find myself in complete sync with his views. As an introduction to his work, this two-film Blu-ray release from new label Anti-Worlds is exemplary, featuring top-grade transfers of both features and a slew of special features, including excellent commentary tracks on both films. The only mystery for me is why this release was marketed as Relaxer rather than the double-bill of Potrykus features that it most definitely is, but that’s just a pause for thought, not a complaint, as I have none about this superb release. Clearly not for everyone, but if you’ve been on the lookout for some quality slacker cinema then you’ve definitely come to the right place. Highly recommended.

|