| |

| Betsy: |

First, push the man, then the issue. Senator Palantine is a dynamic man. An intelligent, interesting, fresh, fascinating... |

| Tom: |

You forgot sexy. |

| Betsy: |

Man. I did not forget sexy. |

| Tom: |

Listen to what you're saying. You sound like you're selling mouthwash. |

| Betsy: |

We are selling mouthwash. |

|

| |

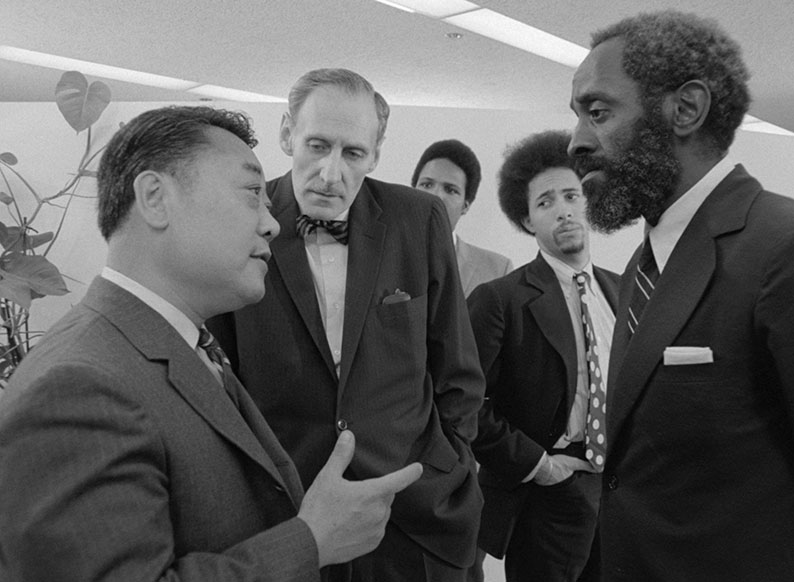

Campaign headquarters chatter in Taxi Driver |

I detest commercial advertising in almost all of its forms. Might as well get that one off my chest before I start, and if you think I’m exaggerating, you’ve clearly never met me. I have a particular loathing for the filmed commercials that used to drive me up the wall back when I still watched live TV and that now curse every visit I foolishly make to YouTube. That said, I’ve become quite adept at using keystrokes and remote control buttons presses to mute and hide the commercials in question, or even skip past them. So hostile am I to their lies and painful lack of artistry, that if I inadvertently catch one, I make a point never to buy the product it is hawking. This goes some way to explaining why you’ve never seen an advertising banner on Cine Outsider, even for movies, which is what we’re all about. Yes, we’ll often embed trailers in news stories, but we do so because some people do rather enjoy them. I rarely watch them myself, though my antipathy on this score stems largely from the often ridiculous number of spoilers and footage from the climactic scenes that most modern trailers seem to contain.

A tad ironically, perhaps, the first professional film job I ever had was for a small production company that made commercials for cinema and TV. It was a place where talented people could command outrageous salaries for creating visually attractive but ultimately vacuous dross, designed to con you into parting with money for something you don’t need and probably never really wanted. It’s perhaps no surprise that I didn’t stay there for long, and I am convinced to this day that this brush with the advertising world made a serious contribution to my early decision to walk away from commercial film production. Oh, to be in my less cynical early twenties today, when we all have the technology we need in our pockets and on our laptop computers to make our own movies without having to budget for film stock, processing and equipment hire. There are even digital platforms to which we can upload the completed work. Of course, it might then get plastered with ads by the platform’s algorithm, which brings me back to where I started this personal but obliquely relevant rant.

Putney Swope is the sort of title that will likely mean little to those new to the film to which it is attached. It’s certainly one that would instantly pique my interest had I not already become aware of the film’s reputation as a prime example late 1960s counterculture cinema. And while it’s far from the only film to take its title from the name of its lead character, the one created for this particular movie seems to have been chosen because it sounds more like a product than a person’s name, albeit one whose purpose and origin is unclear. Then again, perhaps this reading is influenced by the world in which the film is set, that of a Madison Avenue advertising agency. Mad Men, however, it most definitely is not.

The setup is straightforward enough, but that’s the only thing about this extraordinary film that is. Whilst addressing a board meeting of his successful New York ad agency, middle-aged chairman Mario (David Kirk) has a heart attack and dies. The assembled board members quickly set about choosing a successor, and after being reminded that they cannot vote for themselves, most vote instead for the only black member of the board, Putney Swope, primarily because they all believe that he is least likely to win. The newly elected Swope immediately fires all of the white board members and replaces them with people of colour, and changes the name of the agency to Truth and Soul Inc., his aim being to revolutionise the world of TV commercials.

The 60s artistic underground radicalism that infuses almost every scene in Putney Swope is evident from the dizzying opening aerial shot of Manhattan and the off-key musical drones, whines and clangs that accompany middle-aged motivational speaker, Alvin Weasely, as he descends in a helicopter towards the city. He carries a chained-up executive briefcase but dresses like a Hell’s Angel from the ‘Mensa’ chapter, and is met at the helipad by Nathan (Stanley Gottlieb), the company’s lanky business manager. As Weasely and Nathan meet, the two hit a high-five without breaking a step, and a contemporary, guitar-driven rock track kicks in and stays with them as they stride purposefully towards their destination. When they walk into the company boardroom, Weasely stands before the assembled executives and delivers an inane twenty-second speech about beer and masculinity, a slice of corporate motivational bollocks for which the company has apparently forked out £28,000. He then smartly exits, leaving a substantial part of his audience bemused. One sycophant still claims that Weasely’s words were somehow perceptive, while another is instantly inspired to start dreaming up tacky new ad slogans for Harvey’s Beer.

Come at this opening for the first time unprepared and it can seem a little jarring and even disjointed. Watch it again after seeing the whole film, however, and it makes perfect sense, as it’s here that writer-director Robert Downey lays out his gameplan for what is to follow, establishing from the opening frames that what unfolds is not meant to be taken literally but read in exclusively metaphorical terms. This is confirmed when Mario keels over and dies. Nobody calls for medical aid, and he is instead quietly looted of his jewellery and his wallet, and his body is left lying on the table as the executives proceed with the process of selecting his replacement. I can find no direct connection, so perhaps it’s a sign of these revolutionary times that just three months after the film’s US release, British TV saw the arrival of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, aspects of whose surrealistic, anarchic, absurdist comedy are in full evidence in Downey’s film.

Almost nothing here plays out realistically, but every encounter and every decision made by Swope is representative of a degree of societal, behavioural or corporate truth. Then prejudicial norms are flipped on their head, with a white bespectacled messenger repeatedly berated for using the elevator reserved for the black executives, and the only white manager is revealed to be on a lower wage than all of his black colleagues. When the man humbly brings this issue to Swope’s attention, Swope responds – in a spot-on example of managerial bullshit justification – that if he gives him a raise, then everyone else will want one too, and that this will just put them back where they started. This, it transpires, is an inversion of an actual encounter that Downey had with a manager of a company at which he once worked, where his black colleague was on a lower wage than him. But Downey doesn’t limit his targets to white prejudicial attitudes of the day, also satirising the Black Power movement, American corporate capitalism, organised religion (including the Christian and Muslim faiths), political corruption, and popular revolutionary icons of the day, from the Black Panthers to Fidel Castro. Swope himself becomes a symbol of how idealism can be corrupted by money and power, and how the greed this inspires becomes its own motivator, triggering in those it infects the desire not just to get rich, but to own all of the money in the world. For Swope, those around him all become a means to an end, disposable tools for the expansion of his wealth and his increasingly dictatorial sense of entitlement. More than once he has someone dismissed on the spot for ideas that he ends up using and making money from, and at one point he reluctantly (in a really slick montage) marries his girlfriend when she makes that the price of coming up with the successful slogan he needs for a high-prestige product.

Once this patten is established, it becomes increasingly easy to find secondary meaning in even the more absurdist elements, even if this subtext is not always immediately obvious and has sometimes been fortuitously gifted by the passing of time. When Swope acknowledges the talent of job-seeking photographer, Mark Focus (Eric Krupnik), then beats him down in price before dismissing him, it initially comes across as a comment on uncaring corporate ruthlessness, while the fact that Focus keeps returning with the same routine to increasingly curt responses plays as an amusing example of the comedy of repetition. And while it moves into the realms of the surreal when Focus walks unannounced into Swope’s bedroom whilst he and his girlfriend are canoodling to deliver a similar pitch – and later in the US President’s bedroom when he is doing likewise with his wife – it’s easy to see this as a sly dig at the intrusive persistence of the paparazzi, who were already making regular pests of themselves before Putney Swope was made. Having the President and First Lady played by dwarf actors (brother and sister, Pepi and Ruth Hermine), meanwhile, plays like a critque of the conformist image expected of those wishing to stand for elected office and a deflation of that smug sense of self-importance that so many leaders and politicians seem to flaunt. That they invite Focus to join them in bed for a threesome after listening to his job-hunting pitch apparently raised a few heckles on the film’s release, but given the sexual misadventures of the previous American president and our own disgraced prime minister, even this feels genuinely forward-looking now.

Elsewhere, gags that seem to be played purely for laughs also invite subtextual reading, and often have unexpected knock-on effects later. A prime example comes when Swope’s bodyguard (Buddy Butler) threatens the white messenger with a handgun for continuing to use the executive lift. His attempt to then look cool as he returns the weapon to its holster falls flat when it clatters noisily to the floor, forcing him to sheepishly walk back into frame to retrieve it. This not only take a bite out of the macho tough-guy-with-a-gun image that is still so much part of American society and movies, but comes back to haunt the bodyguard later when he really needs that gun and finds that he’s once again misplaced it. This incompetence sees him fired on the spot and transferred to the President’s staff, where he is given a far larger weapon, which makes him look dangerous for a short while but ultimately proves equally ineffective.

Anyone as seduced as I was by first-time cinematographer Gerald Cotts' handsome monochrome cinematography will likely get a sizeable jolt 22 minutes in when the image unexpectedly switches to richly toned colour. In another slice of multi-layered social commentary, the world of corporate advertising is painted in shades of grey, while the commercials themselves are presented in full colour, a nigh-on perfect illustration of how real life is homogenised by advertisers to present us an idealised vision of the world that simply doesn’t exist. Even here, Downey opts to play games with established form, drawing on the conventions of the medium but adding dialogue, lyrics and imagery that would never make it into a TV commercial even today, but which again are symbolic of the company’s supposedly revolutionary messaging. Thus the young man who is told by the narrator of all the good things in the breakfast cereal he is eating responds with a surprised, “No shit!”; a Dinkleberry Frozen Chicken Pot Pie is slapped into the face of a Miss Redneck beauty queen, who responds to a condescending comment from a suited male compere with, “Oh, fuck off, Bert!”; an interracial couple extols the virtues of Face Off skin cream through a song that includes lovingly delivered lines about flashed beavers and dry-humping; and the whole notion of airlines that promote themselves on the beauty of their female cabin crews (yes, this was once a thing) is sent up by lingering shots of half-naked stewardesses bouncing up and down in slow motion (this does go on a bit), and who are then shown climbing amorously all over the male winner of a Lucky Airlines special ticket. My favourite is probably the simplest but also oddest of all, and involves a woman who just oozes natural cool grooving towards the camera down a littered alleyway to a funky rock track, then pausing in mid-shot just to tell us, “You can’t eat an air conditioner,” before dancing back the same way until she is completely enveloped by expanding plumes of smoke.

Putney Swope is a gloriously contradictory movie, one littered with fly-by-wire filmmaking and performance improvisation but whose every shot, exchange and action feels planned to perfection. In many ways a product of the underground film movement of its day, it was nonetheless a commercial success and still feels fresh, vibrant and funny over 50 years later. Its cast is a mix of professional actors and amateur first-timers chosen for a particular look or trait, and it’s genuinely hard to distinguish between the two. It helps that even the small roles – and there are a lot of them – have been cast with care and as a result really register, some of whom I’m unable to identify by name because of the playful assignment of names in a cast list that also seems to have a couple of significant omissions, and even falsely (and perhaps mischievously) claims that Mel Brooks has a supporting role. There are also a smattering of faces who found a degree of fame in later roles – of particular note on this score is Antonio Vargas (later to become an audience favourite as Huggy Bear in Starsky and Hutch) as an unnamed Arabic executive who repeatedly berates Swope for betraying his original intentions, and in the end proves to be the only committed revolutionary of the group.

No fence-sitting here, I loved Putney Swope to bits. It breaks rule after rule of established film storytelling, but in a way that makes complete and oddly logical sense, rejecting naturalism for metaphor and yet somehow remaining honest and truthful right up to the final scene. Even the gravelly post-dubbing of lead actor Arnold Johnson’s voice (by Downey himself – more on this in the special features) ends up working for the film as a symbol of the false face of the products that he and his team are so amorally hawking. And despite having a white director and a universal message, the film features a primarily black cast at a time when strong roles for black actors were still shamefully rare, and counts amongst its modern day fans several notable black comedians and actors. It’s a late-60s counterculture gem, made with wit, genuine humour, and real socio-political bite, with some of the most acerbic digs tucked inside seemingly jokey exchanges. When a chemist hired by Swope to devise new products presents him with a top-notch window cleaner whose commercial potential is hampered by its unpleasant odour, for example, Swope responds, “As a window cleaner, forget it. Put soy beans in it for protein and we’ll push it as a soft drink in the ghetto.” But when it comes to lines that still feel a little taboo-busting today, look no further than the second of three calls that come in about Sonny Williams, the company’s talented but socially troublesome (white) copywriter. “Sonny Williams got picked up at the Bronx Holiday Inn with a thirteen-year-old girl,” Swope is wearily informed, to which he replies, “At least he’s not superstitious.”

Putney Swope was restored in 4K by the Academy Film Archive and the Film Foundation, with funding provided by the George Lucas Family Foundation. The restoration used the original picture negative, fine grain master, TV/censored version magnetic sound master, and original optical track. The resulting transfer looks terrific. Framed in its original Academy aspect ratio or 1.37:1, it boasts a wonderfully toned greyscale on the monochrome footage and vibrant colour on the commercials, both with solid black levels that do not suck in surrounding shadow detail. The image is sharp, with fine detail crisply rendered enough to clearly identify shots in which the depth of field was riskily narrow, plus a small number where the focus was just a tad soft. There are no traces whatsoever of any former wear, and a fine film grain is just visible. A marvellous transfer.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack does have some inevitable restrictions to its dynamic range, but otherwise is clear and free of wear or background fluff.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Robert Downey

This 2001 audio commentary by writer-director Robert Downey is a hugely valuable inclusion, as while it has its brief pauses, it’s also littered with wry comments and interesting background information on the film. If you start with this, however (I certainly did), be ready to hear some of the stories told here repeated elsewhere in the special features. Subjects covered include the film’s real-world inspiration, the low budget, the casting, the performers, the decision to dub of Arnold Johnson’s voice, getting to use actual Chase Manhattan ad agency offices for the main location, the evolution of certain scenes, the risk taken with the alarming-looking late film fire, and plenty more. I was particularly amused by the revelation that when filming the opening boardroom scene, the black actors had to all hide under the table, as everyone was confined to that room whilst they were shooting there. Downey is also refreshingly, if unjustly, self-depreciating – “Is Putney Swope my favourite film?” he says in response to what was likely an unheard question, “Uh, no. I don’t like any of ‘em.”

Audio Commentary with Sergio Mims

Recorded in 2019, this second commentary by film critic, film historian, journalist and co-founder and co-programmer of the Black Harvest film festival, Sergio Mimms, effectively expands on the information provided by Downey and examines not just the film itself, but its production, release and influence on later filmmakers. Areas covered include director Robert Downey, editor Bud Smith, several of the actors and their casting, independent distributor Cinema 5 and its founder Donald Rugoff, the central theme of absolutely greed corrupting absolutely, the satirising of the Black Power movement, and much more. He reveals why Jane Fonda was instrumental to the film’s box office success, discusses its impact in the context of the American political situation of the day, and provides a useful breakdown of how filmmakers spent years chipping away at the Production Code, and how it was eventually replaced by the modern rating system. Another excellent companion to the film that compliments Downey’s commentary rather than duplicating it.

Interview with Robert Downey (16:08)

A 2001, 4:3-framed video interview with Downey, who does cover some of the same ground here as in his commentary, including the ad agency incident that inspired the film and the dubbing of Arnold Johnson’s voice, but there are more than enough stories that are new to this extra to make it a most worthwhile watch. Topics of discussion include his early days of shooting experimental commercials, the film’s release by Cinema 5 when no other distributor wanted it, his opening title credit as ‘a prince’, and how this film and a handful of other counterculture works – notably Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider and Frank Perry’s Last Summer – held a mirror up to changing times. He confirms comments made by Sergio Mims about Paul Thomas Anderson’s love of the film, and describes that director as “a 30-year-old guy who knows more about the 60s than I do.”

Interview with Gerald Cotts (19:41)

An audio interview with Putney Swope cinematographer Gerald Cotts, conducted for the 2019 Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray edition by Brad Henderson, who as ever proves adept at asking questions that prompt interesting and sometimes revealing answers. Cotts looks back affectionately at the wonderful degree of freedom they all had on the film, at learning on the job and figuring things out as they went along, and how he gravitated towards cinematography in film school and ended shooting this, his first feature, despite having no prior experience with 35mm. He reveals that the considerable amount of marijuana smoked on set did sometimes impact on productivity, talks about the film’s premiere and its later influence, and confirms that he still holds it in very high regard. There is one point, however, on which he contradicts Downey’s version of events. Downey claims more than once on this disc that leading man Arnold Johnson was visually right for the part but couldn’t remember his lines, and that the idea of redubbing him came from Cotts when he realised that the actor’s beard made it impossible to see precisely what he was saying. Cotts seems to have no memory of this, and even disputes the assertion that Johnson had trouble remembering lines, instead suggesting that Downey had some issues with the actor and made the decision to redub him later at the editing stage. We may never know for sure.

Film Forum Q&A with Robert Downey (33:51)

An archival audio recording made at Film Forum New York 20 May 2016 after screening of Putney Swope, featuring director Robert Downey in conversation with Bruce Goldstein, the Forum’s director of repertory programming, who also provides a brief introduction. Again, some of what is discussed here is also covered in the commentary, but there’s an easy-going and even comically offhand edge both to Downey’s responses and even Goldstein’s questions and comments, which give it all a fresh and entertaining feel. One small portion of the exchange suffers a little because we are unable to see projected slides being discussed, but there’s still much that is engaging and specific to this extra, including the revelation that Downey was a serious sports jock in his college days. Questions from the audience are included, some of which also spark comical responses.

Theatrical Trailer (2:32)

I can think of clips galore that could be used to promote the film’s many qualities, so was a little surprised by what is served up here, a shot of the bouncing women from the Lucky Airlines commercial, then the whole of the Face Off pimple cream song. There’s no black-and-white footage and no shots of Swope, and while the satire is there in the lyrics of the song, I’m willing to bet some of those who saw the movie based on what they saw in this trailer got a few surprises.

Dan Ireland Trailer Commentary (3:00)

In this Trailers from Hell introduction and commentary, The Whole Wide World and Jolene director Dan Ireland reflects on how Putney Swope came to be, then briefly outlines the plot, recalls the audience reaction the cinema screening he attended, and admits that it’s a film that he regularly revisits.

Radio Spots (0:57)

Two (almost) 30 second radio spots, the first of which consists of an extract from the Face Off song, but with the words “dry hump” bleeped out (which can’t help but suggest that something more explicit was excised), the second made up of three shouts of “Putney says the Borman Six girl has got to have soul!” and nothing else. I guess it seems only right that a commercial for a film about a company that creates unconventional commercials should be, well, unconventional.

Image Gallery

25 screens of promotional stills and posters.

Booklet

The main essay here is a most enjoyable and smartly observed look at the film by critic, author and journalist, Christina Newland, who rightly notes up front that over a half-century later, it’s still funny. Next is a 1969 article from the Los Angeles Free Press by Richard Whitehall that looks at Robert Downey’s underground film career, with particular focus on Putney Swope, and notes that at a preview screening the black audience members “were more instantly and fully with the movie than the whites.” Following this is an interesting interview with Downey, conducted for Movie Journal by Jonas Mekas, who was himself a key figure of the New York avant-garde filmmaking scene and who was not as impressed with Putney Swope as he had been with Downey’s previous films. At one point the two even swap places and Downey interviews Mekas about the film, but it doesn’t get very far. Extracts from three contemporary reviews follow. David Wilson in Monthly Film Bulletin is curtly dismissive, concluding that “Visual graffiti of this order don’t merit public exposure” (ouch), but Vincent Canby’s New York Times review – quoted more than once in the on-disc special features – nails it with its opening line, “To be as precise as possible about [Putney Swope,] it is funny, sophomoric, brilliant, obscene, disjointed, marvellous, unintelligible and relevant.” Full credits for the film are included and the booklet is illustrated with publicity material.

There’s so much crammed into Putney Swope that I had to draw a line under a review that could have been considerably longer than it already is. Its reputation as a mischievous counterculture classic is well earned, and its vibrancy, energy and imagination effectively nullify any elements that have been dated by the passing of time. Indicator has done the film proud here, with a corking transfer, two terrific commentaries, and a host of other high quality special features. Love it. Highly recommended.

|