|

There are two distinct ways that a film can work to convince an audience that something is amiss in a drama even if the dialogue gives no clear indication of what. Most commonly, it will be visible in how the characters behave, how they deliver certain lines or react to each other or specific situations. It can also be conveyed through the filmmaking itself, in the choice of camera angles, the use of music and even editing decisions. This, when it works, is the more interesting approach. But what happens if you seamlessly combine the two? The too-little discussed 1964 British psychological drama Psyche 59 is a film I was previously unaware of, one that most effectively unsettled me for almost whole of its 94-minute running time.

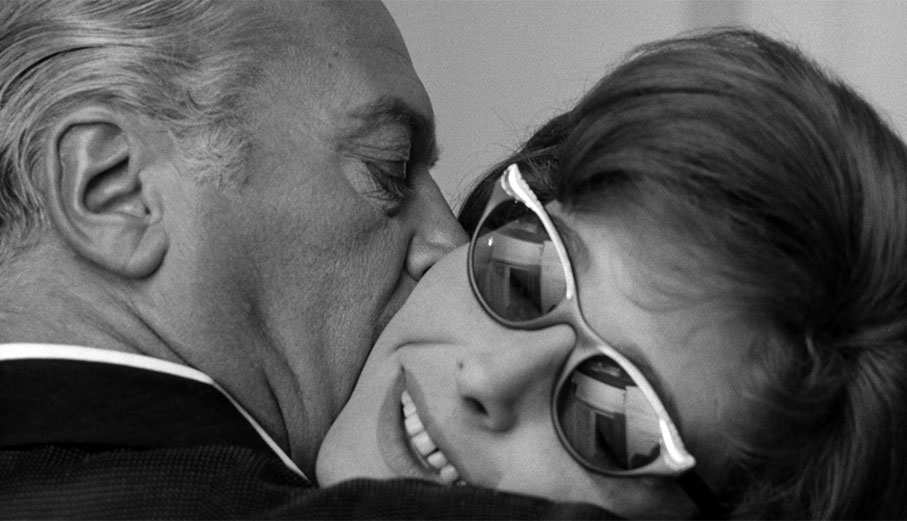

Following a title sequence that almost suggests we're about to watch an Amicus horror, the story kicks off with an interesting bit of misdirection involving documentary-style footage of a woman named Allison (Patricia Neal) and her companion Paul (Ian Bannen) riding horses through London, then cheerily conversing and walking hand-in-hand in a manner that strongly suggests that they are a couple. When they return home, however, Alison walks in and trips over an unfortunately placed suitcase, and it's only then that we discover that the sunglasses she's wearing are not for show, but because she is blind. What's more, the bag in question belongs to her husband Eric (Curt Jurgens), who has just returned from a business trip abroad and whom Allison, after gleefully embracing her two young children and leaving them in Paul's care, makes her way into his study to greet. I should point that even at this stage I was still under the impression that Allison and Paul were a couple. The children are clearly Allison's and their first words to her are "Daddy's home!" but the assumption I made in an instant was that she and Eric had separated and he was visiting purely to see his kids. This seems to be confirmed when Allison enters the study and Eric, who is on the phone talking business, makes no attempt to break off from his conversation and greet her. Yet there's something in Allison's expression and body language that suggests she is aching for Eric to finish his call so that he can focus his attention on her, which is turned up a notch when Eric picks up a wooden spatula from his desk and starts stroking her leg with it, a move she has an almost sexual response to.

If it seems that I've gone into more detail about this opening four minutes than is right for a regular plot summary, it's because the tone for much of what follows is set here, particularly the sense that there is – or perhaps was – more to the characters and their relationships with each other than surface impressions suggest. This is seriously stepped up when Allison's younger and more carefree sister Robin (Samantha Eggar) arrives to stay following the collapse of her marriage and begins subtly suggesting to Allison that her husband is not to be trusted whilst simultaneously seductively toying with the man. Intermittently Robin and Paul behave like a couple but it's clear that Robin doesn't take Paul's attraction to her all that seriously. "Why won't you marry me?" he asks her after they have kissed passionately on a deserted beach, to which she coolly replies, "because you don't love me," a response that Paul appears downcast by but makes no serious attempt to challenge.

Almost every scene and every verbal exchange not only casts uncertainty on how each of the four leads really feel about each other, but also what happened between them in the past to cause such a level of barely suppressed hostility, something that steadily inches its way to the surface as the film progresses. Questions about all four of them start to arise. Paul is in a relationship with Robin but has a connection with Allison that appears to go a little beyond friendship. Is he attracted to Robin purely because she is Allison's sister? Was he involved with Allison before she met Eric? Eric's been his friend for a number of years, but Paul clearly harbours a barely concealed hostility towards him, particularly over his attitude to Robin, his infidelities and his brutish leanings. Is Paul resentful because of how he believes Eric treats or has treated Allison or Robin or both? And what of the seemingly carefree Robin, who seems determined to sour the marriage of a sister she seems fond of and clearly has designs on Eric that flit between hostility and desire, something that infuriates Eric in a manner that he feels unable to openly express?

This constant uncertainty ensures that keeping company with these characters is often akin to visiting a friend's house while his or her family are constantly arguing with each other in the background – try though you might to ignore it, all you really want to do is get the hell away from a fight that you have no dog in. As suggested above, this discomfort is not solely down to how the characters behave towards each other, but also to director Alexander Singer's penchant for unexpectedly cutting to extreme closeups of eyes, mouths, hands or inanimate objects, often as a visual representation of Allison's blindness and fractured memory, but also to break the generally accepted rules of scene editing structure in a manner that proves (and is doubtless designed to be) disconcerting. At its most deliberately jarring it tells us nothing specific, but does help to clue us into the fact that something is very wrong here – I'd even suggest there's a sizeable essay's worth of analysis on the use of the close-up in Psyche 59 if there's a film student out there looking for a subject for their dissertation. Adding a further layer of discomfort is composer Kenneth V. Jones's score, which rarely compliments the imagery and instead almost seems to deliberately kick against it, adding a sense of troubled disharmony to even seemingly peaceful scenes and encounters.

As the story progresses, it becomes clear that much of the inter-character hostility has its roots in an unspecified trauma of some years earlier. This is established early on by the casual revelation that Allison's blindness is not a physical ailment but a psychological one that was triggered by an incident she is unable to recall and that caused her to fall down the stairs in shock. On hearing this, those familiar with such tales will be sure of two things, that the film will build to a shock revelation about Allison or Robin's past and that a second emotional jolt will likely prompt Allison to regain her sight and memory in the final act. I'm saying nothing about whether her sight is restored or not, but it is worth noting that the expected revelation does not come as a surprise at all. This is partly down to the dampening effect of the passing of time – what startled us once will almost always seem a lot tamer today – but largely to the fact that the film does not to play this as a shock reveal at all and instead elects to telegraph the scene in question some time before confirming what the audience by then should already have surmised.

The cast is a key attraction here. Patricia Neal's performance as Allison was marked down in some quarters on the film's release, with claims made that having to act behind dark glasses limited her range, especially coming on the tail of her Oscar-winning turn as Alma Brown in Hud, a gripe with which I'm happy to disagree. For me, she brings an almost desperate sense of longing to Allison that makes it easy to believe she would always take Eric's side against Robin and reject any attempt on her sister's part to drive even the smallest wedge between the them. Curt Jürgens also copped a little flack for what some felt was a rather one-note performance and I do understand that, but what he does here is right for the character and the role, particularly his pent-up anger at Robin, which we know there is more to than surface behaviour suggests. What time has left me less comfortable with is the notion that the nominal bad guy of the story is the one with the foreign accent, a now weary and casually xenophobic trope that seems to be making a comeback and gets cheerfully ignored by those praising the qualities of John Wick and the like. Ian Bannen hovers intriguingly in the background as Paul, buttoning up his frustration but a dab hand at throwing looks of barely supressed distaste at Eric. These become more pronounced when the two drive out to the country to pay Allison and Robin a visit – the expression on Paul's face as they stop for fuel and Eric immediately starts chatting up a female customer says a lot about the contempt in which holds his supposed friend, and it's certainly easy to side with Paul when Eric dispenses this little pearl of advice about what Paul should do to get Robin to take him seriously: "Beat her. Use your hand, use your belt. When she's had enough, make love to her." What a charmer. There's a nicely low-key turn from Beatrix Lehmann as Eric's kindly mother, who really comes into her own in a scene where she quietly pesters someone away from possible suicide without ever revealing to that's what she's really doing. Yet stealing just about every scene she's in is the then 25-year-old Samantha Eggar, who is just electrifying as Robin, bristling with confident and seductive intent and driven by a long-game determination to get her way whatever the cost to those she nominally cares for. Even today, the strength and sensuality of her performance is eye-opening – back in 1964 it must have felt genuinely provocative.

Psyche 59 is a film that makes for intriguing but rarely comfortable viewing, one that initially seems to be building to a big revelation whose nature is revealed long before the moment most films would choose to deliver a startling surprise. The film's primary concern is not the event itself but how it has affected the relationships between the four characters at it is core, and in the respect I'd say it really delivers, thanks to some sharp writing by Julian Zimet from Françoise des Ligneris' novel, a quartet of strong performances, Alexander Singer's purposefully off-key direction and arresting work from cinematographer Walter Lassally, editor Max Benedict and composer Kenneth V. Jones. Despite being made to feel distinctly uneasy by my first uncertain viewing, I couldn't get the film and its imagery out of my head and found myself repeatedly revisiting specific scenes and moments with a constantly refreshed critical eye. In spite of a tonally positive spin put on an ending that has the potential to bemuse but about which a small essay of conjecture could be written, it's a downbeat film that tackles issues that would have been considered off-limits just a couple of years earlier, one in which selfish people behave destructively towards those they by rights should deeply care for, and is distinctive enough in style and tone to be worthy of this rediscovery. Nice one, Indicator.

Sourced from a Sony HD master, this 1.75:1 1080p transfer is in typically fine shape, boasting a generous tonal range to the monochrome image, with contrast that feels punchy but never sucks detail into the inky blacks. The level of picture detail is excellent, a fine film grain is visible and the transfer is clean of dust and damage. There is a very slight jitter on a couple of shots during a restaurant scene, but these do not last long and could well be an issue with the source material.

The Linear PCM mono 1.0 track is very clear with some minor but expected limitations in dynamic range, and no background hiss or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

The BEHP Interview with Walter Lassally

An archive interview with the film's director of photography, Walter Lassally, conducted by Roy Fowler as part of the British Entertainment History Project in what sounds like Mr. Lassally's home (distant background noise includes passing traffic and hammering), one that provides a welcome insight into this esteemed cinematographer's life and career. Subjects covered include his childhood in Weimar Germany and his family's move to London, his early work in photographic processing, his first film work on technical films and documentaries, his surprise at finding that most people working in the movie business were not film buffs, his feature work as director of photography and much, much more. His comments on the appeal of tape recording over film are interesting and have been borne out by the subsequent advances in digital recording equipment and media, and there's an engaging story about the time he was investigated by the Special Branch due to the political leanings of people he was filming. A valuable inclusion, and it looks like more of these BEHP interviews are heading for future Indicator releases.

Come to Silence (11:53)

A welcome interview with a splendid Samantha Eggar, who succinctly outlines what drew her to the part and reveals the making of the film was a great experience and that the actors and crew were like a tight-knit theatre company. Having only watched it recently (presumably in preparation for this interview), she is struck by Walter Lassally's cinematography and the clean, black-and-white tones of the production design, as well as her own performance ("Where did that come from?"). She also has some interesting things to say about truth and screen acting, and sums her character up laughingly with the comment, "It's just sex, darling!"

Intangible Visions (13:14)

Composer Kenneth V. Jones looks back at his work on a film he remembers enjoying enormously writing the score for, as well as discussing the challenge he faced after taking on board what Patricia Neal wanted to do with the role and how he could reflect that in the music. He talks specifics of composition, notably something known as the 12-tone technique that a non-musical oaf such as myself knows nothing about and which he suggests is inconvenient for editors who prefer straight bars and regular beats. Get with the groove, guys.

An Abstract Quality (10:26)

Critic, lecturer and broadcaster Richard Combs looks at the career of director Alexander Singer, who only made five features during his long career and worked primarily in television – indeed, I knew his name primarily for his work on Star Trek: The Next Generation. He reveals that Singer was schoolfriends with a certain Stanley Kubrick and was more proactive than him in developing ideas and was instrumental in persuading our Stan to become a film director (he initially favoured cinematography) and even worked uncredited on two of his early features. Combs also examines elements that run through all of Singer's features and shares information on his later work – he's currently 90 years old but still working on science-based projects.

Theatrical Trailer (2:44)

"The screen prowls the darkest corridors of the human mind to the lonely place where lust hides…" or so the trailer assures us before dishing out a few spoilers.

Image Gallery

20 slides of production photos, front-of-house stills and posters.

Booklet

Following the expected full film credits, the booklet kicks off with a detailed, exhaustively researched and educational essay by BFI National Archive curator Josephine Botting on the film, its making and the changes made to the source novel. Next up, there is a clear and concise explanation of the film's title, a piece that does not appear to be credited to a specific author so I can't throw any praise at them, but their efforts are welcome. Reproductions of pages from the official campaign book make the film look like a William Castle production, and include suggestions for a questionnaire titled, "PSYCHE 59" Girls All Over Town. If you've seen the film, the prospect of that is not an encouraging one. The expected extracts from contemporary reviews are present, and high praise is in very short supply here, with William Mootz of the Louisville Courier Journal describing it as "dreary nonsense." Promotional stills and artwork have also been included.

An unusual, discomforting and downbeat work that remains consistently interesting for its performances and its filmmaking and is a work I am sure I'd never have seen were it not for this new Indicator Blu-ray. As ever, the disc delivers on all fronts, boasting an excellent transfer and a fine collection of special features. Recommended, but I'd leave your happy shoes at the door.

|