| |

“Let the states of equilibrium and harmony exist in perfection, and a happy order will prevail throughout heaven and earth, and all things will be nourished and flourish.” |

| |

Confucius |

| |

“It strikes me profoundly that the world is more often than not a bad and cruel place.” |

| |

Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho |

In San Francisco’s Chinatown, elderly Chinese philosopher Chang Lo (E.A. Warren) is a widely respected figure, even amongst the Caucasian criminal fraternity. He has even managed to persuade former underworld kingpin ‘Silent’ Madden (Ralph Lewis) and his daughter Molly (Priscilla Dean) – aka ‘Silky’ Moll – to abandon their criminal past and follow the path of enlightenment as taught by Confucius. Deeply unhappy with this for reasons best known to himself is a ruthless criminal named Black Mike Sylva (Lon Chaney). To that end, he’s making plans with his right-hand man, ‘Dapper’ Bill Ballard (Wheeler Oakman), to frame Madden for a crime serious enough land him an extended period in jail, the aim being to turn Madden and Molly back to the dark side, something Madden believes he will then be able to turn to his advantage. The plan proves successful, and Madden is falsely convicted and imprisoned for shooting a policeman, which prompts the infuriated Molly to reject Chang Lo’s teachings and team up Bill and Blackie to pull off a jewel robbery, unaware that she is being set up by Blackie to take the fall.

Outside the Law was an early collaboration between director Tod Browning and actor Lon Chaney, and the general consensus seems to be that it’s a relatively minor one, at least when compared to the likes of The Unholy Three (1925), The Unknown (1927), and West of Zanzibar (1928). Indeed, while Chaney was the headliner in all three of those films, plus a few more besides, here he’s effectively a supporting player. The trick is that he plays two very different roles, the ruthless Black Mike and… well, I’ll get to the second character in a minute.

The actor whose name is above the title here is Priscilla Dean, with whom Browning had previously worked on The Virgin of Stamboul (1920) and with whom he would subsequently make Under Two Flags (1922), Drifting (1923), and White Tiger (1923). She’s certainly a lively and expressive presence, particularly after she and the love-struck Bill decide to double-cross Blackie, and end up hiding in an apartment with the stolen jewels. That said, she’s outshone a bit by Wheeler Oakman’s more reality-grounded performance as Bill, except when he’s interacting with the film’s most unpleasant character, a horrible ‘cute’ moppet (Stanley Goethals) from the room across the hall, a child that Bill seems to have almost adopted as his own. He certainly hugs and kisses him a lot. Yeah, about that… The impact this mawkish creature, his dog and its army of new-born puppies (oh, you’d better believe it) has on the couple is, as pointed out by Kim Newman on this very disc, the most implausible aspect of a film that is peppered with moments of suspect logic. Religion also plays its unwelcome part, but it’s the transformative effect the child has on the more sensible Molly that is the hardest to swallow – with just a few tears and a hug, he melts her previously resistant heart and awakens in her a desire to just settle down with the man she now suddenly loves and have a similarly cloying offspring of her own. I’d love to have seen the kid try that shit on Blackie and see where it got him. And you don’t want to mess with Blackie. Chaney plays him as an archetypal silent movie bad guy, which in a way he was. Armed with a face carved out of the hardest granite and the sort of malicious grin that would give children nightmares for weeks, he certainly represents a palpable threat.

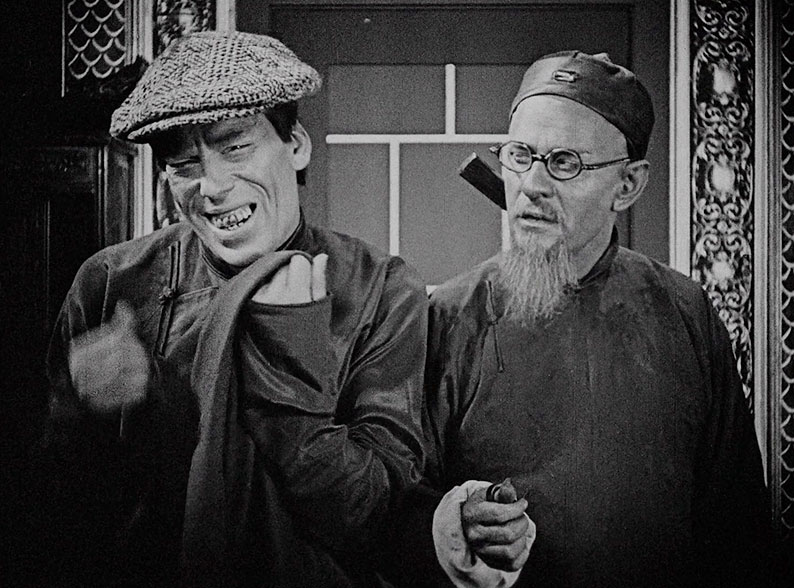

And what of Chaney’s second role? Ah, well, before I get to that, a brief contextual reminder is probably in order. Back in 1920 and for a good many years after, it was common practice in Hollywood for prominently featured ethnic characters to be played by Caucasian actors in heavy makeup. It’s this convention that shot Swiss actor Warner Oland to fame playing Chinese detective Charlie Chan in a slew of movies in the 1930s, the very same decade in which the Austro-Hungarian Peter Lorre had similar success playing Japanese secret agent Mr. Moto. Thus, when approaching any Hollywood movie from the first half of the twentieth century featuring non-white characters, certain allowances do have to be made. But even with that in mind, Chaney’s portrayal of Chang Lo’s Chinese manservant, Ah Wing, still prompted a few involuntary winces on my part. The epicanthic folds are well enough done, but Wing’s squinty-eyed looks, gaunt cheeks, and goofy false teeth do tip the portrayal uncomfortably towards caricature. Indeed, the teeth are so large that they seem to make it impossible for Chaney to completely close his mouth, and when pondering or eavesdropping on the plotting of others, he looks almost as if he is shifting them around in his mouth in discomfort.

The cartoonish nature of his character is highlighted further by the relative subtlety of E.A. Warren’s portrayal of Chang Lo – the actor here may also not be Chinese, but the calm restraint of the portrayal feels altogether more convincing and respectful. And it’s a shame, as Wing proves to be both a loyal and resourceful companion, a force for honour and righteous action in a world littered with criminal minds. And issues with casting conventions of the day aside, it’s here that is part of the film’s undeniable appeal. Although set primarily in San Francisco’s Chinatown, in Outside the Law all of the criminals are white, while the two brightest beacons of goodness are Chinese, one of whom is widely respected by criminals and law enforcement officials alike. In some ways, they helped to pave the way for Warner Orland’s portrayal of Charlie Chan, an albeit stereotypical Chinese detective who is repeatedly shown to be smarter than the Caucasian cops that he assists. Indeed, so effective is Chang Lo at persuading individuals on both sides of the law to follow his advice that I was left with the feeling that if he was elected to the Presidential Office, the whole of America would soon be at peace, with its citizens living together in multiracial harmony. The Confucius quote that opens the film suggests that Browning may have been of a similar mind.

That this crime drama is put on hold for a while to become an ultimately unconvincing romantic melodrama (that bloody kid…) should not detract from the fact that when it is a full-blown crime drama, it delivers the goods. The street shoot-out used to frame Madden is fast and furious, the mansion jewel heist is well staged, and a physical bust-up between Bill and Blackie is as convincingly desperate and violent a scrap as I’ve seen in a movie all year. Browning’s use of cross-cutting to build tension and accelerate pace is also impressive and at times disarmingly modern, adding credence to the theory that the cinematic sluggishness of some sequences in Dracula (1931) was more the exception than the rule for this oft-underrated director. It’s this directorial confidence, together with some solid work from a consistently interesting cast (which includes, in a small early role, rising star Anna May Wong), that makes Outside the Law an enjoyable and worthwhile watch even today, one whose lasting qualities easily outshine the elements that the passing of time have rendered akwardly outdated.

As the title sequence concluded and film proper began, I had to initially pick my jaw up from the floor. A key word here is ‘initially’. Outside the Law was made in 1920, over a century ago, and the 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray was sourced from a 4K restoration by Universal Pictures, which as far as I am aware (and I’ve not been able to confirm this) was created from a single nitrate print discovered in a Minnesota Barn in the 1970s. Since then, a second print was apparently located in Yugoslavia, which may or may not have also provided material for the restoration. The transfer here is certainly consistent with what I’ve read about the Minnesota print, much of which was apparently in excellent condition, and that is certainly reflected in the gorgeous image quality during the first half of the film. The contrast is well balanced, with solid black levels and no burn-outs on highlights, and the crispness of the detail is genuinely outstanding, being sharper and clearer than a good many transfers I’ve seen of films made years and even decades later. Film grain is always visible, and while some chemical damage flickers intermittently on the left or right edge of frame and a few scratches remain, they are rarely distracting. Some serious work has clearly gone into cleaning up other dirt and wear. A remarkable job.

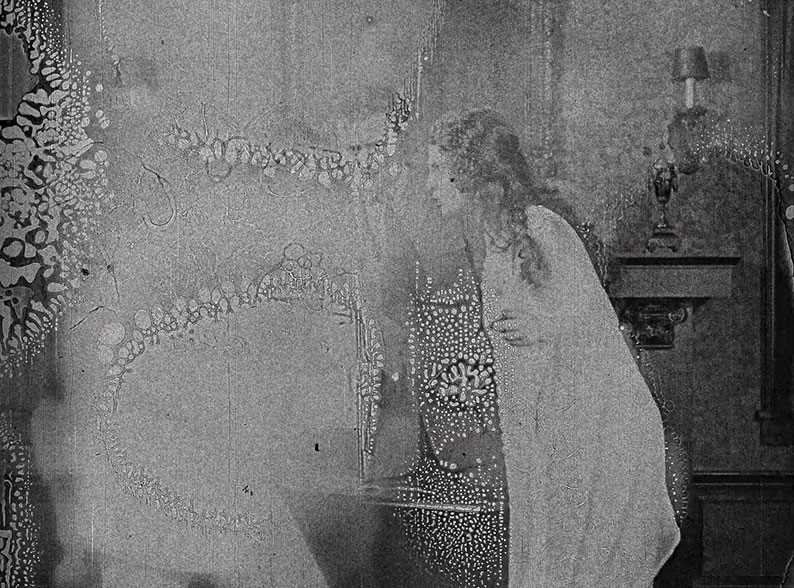

An example of the nitrate decomposition (above) and how good the image can look (below)

There is, however, one rather sizeable caveat, one that all prospective viewers would do well to be ready for. Although noted for its otherwise excellent condition, one issue with the Minnesota print was that two sequences had suffered extensive decomposition, and when I say extensive I’m talking about damage that is far beyond repair for even the most talented of restoration teams. When it starts to kick in, you quickly realise that you’re in for a rough ride, and at its worst it all but obliterates the image, a series dancing explosions of nitrate decomposition that I have no doubt would have Decasia director Bill Morrison hugging himself with glee. Astonishingly, even during this firework display of damage, the image itself remains stable in frame, which surprisingly helped me keep tabs on what was going on beneath this blitz of corrosion. Given that no complete, undamaged print has been located, this is likely as good as the film is going to look for the immediate future, and with so much of it looking as good as it does, I found the damaged sections easy to live with. There are a few shots not blighted with this level of corrosion that are visibly softer than the pin-sharp norm, and it’s quite possible these were sourced from the Yugoslav print and used to replace more extensively damaged ones on the Minnesota print. Again, I’ve been unable to confirm this either way.

As for the soundtrack, yes, it’s a silent film, but this transfer is accompanied by a very fine orchestral score by composer Anton Sanko, which is in Linear PCM stereo 2.0 and sounds terrific.

Kim Newman on Outside the Law (20:37)

The always welcome Newman kicks off by examining the film in the context of the careers of Lon Chaney and Tod Browning, and particularly the films on which they collaborated, as well as Browning’s work with Priscilla Dean. When he gets stuck into the film itself, I was almost startled by how closely our views aligned on almost every aspect, including the brutality of a key fight between Bill and Blackie, the lost-in-time awkwardness of Chaney’s performance as Ah Wing, the effectiveness (and influential nature – I missed that) of the heist sequence, and the hard-to-take philosophy and moral turnaround of the two leads. He shared my dislike of the child across the hall, whom he amusingly suggests “will turn the stomach of all kids and most adults watching.” He talks about how Chaney’s portrait of Blackie sets the tone for movie tough guys to follow, gives brief coverage of the remakes (one of which was also directed by Browning), and suggests that the movie must have seemed old-fashioned even in 1920, whilst also acknowledging its legacy.

Alternate Ending (10:06)

Sourced from a 16mm ‘Show-at-Home’ print that is believed to have been adapted from a 1926 re-issue of the film, this version of the final ten minutes of Outside the Law is made up entirely of alternate takes to the ones used in the feature itself. It displays considerably less nitrate decomposition than the main feature, but for reasons known only to those who put this version together, it completely eliminates the energetic final fight and ends instead on some anticlimactic musing on Molly and Bill’s part, the details of which I’ll tactfully avoid revealing here. There is some damage and picture instability, and at one point an alignment issue on the source print sees the top part of the image separated from the rest by a wide black bar.

Also included with the release version is a Collector’s Booklet featuring an essay by Richard Combs, but this was not available for review.

Allowances have to be made for changing times, and my personal aversion to mawkish moppets make the credibility-stretching impact the kid here has on this film’s apprentice Bonnie and Clyde even harder to swallow than it would be anyway, but there’s still much to enjoy and admire here, particularly in the performances and Tod Browning’s tight direction. The nitrate corrosion is severe in places, but elsewhere the image quality is startlingly good, and while there are many supplementary features, you can always rely on Kim Newman to deliver the goods. Recommended.

|