| |

"I always very much admired the director Curtis Harrington. I was friends with him before he passed away. He lived a very, I guess bitter life, in a way. His career, he thought, hadn’t really played the way he thought it should have. He’s very much forgotten, but I think he’s an incredible filmmaker, and I hope something like this could do more justice to how unique he was. Night Tide, which was his directorial debut, is an outstanding piece of cinema." |

| |

Nicolas Winding Refn interviewed on SlashFilm* |

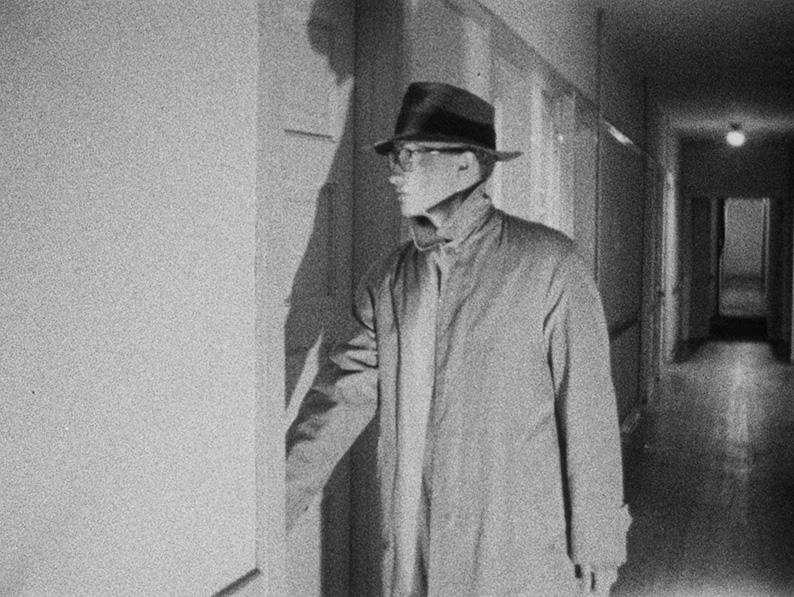

I always like it when I'm able to glean information about a film's lead character just from how they are observed when they first appear on screen. Take director Curtis Harrington's 1961 debut feature Night Tide, which opens on a low-angle shot of Johnny Drake (Dennis Hopper) as he smokes a cigarette and looks out to sea whilst resting his arms on the handrail of the Santa Monica Pier on the Los Angeles coastline in the dark of night. We know Johnny's a sailor because he's wearing his uniform, and the location suggests that he's probably on leave. Yet in movies at least, sailors on leave tend to hang out in groups ("New York, New York, it's a wonderful town!"), unless they are visiting loved ones or friends. And Johnny doesn't look like he has a friend in the world. If you've any doubt about that, the soulful notes of David Raksin's score is on hand to give you a nudge.

Seemingly at a loose end, Johnny wanders the arcades of Venice Beach before dropping in to a basement jazz bar for a drink. He looks out of place in his uniform but the rest of the hepcat customers are too focussed on the music to pay him any heed. Johnny's attention is quickly drawn to Mora (Linda Lawson), an attractive young woman who is sitting alone. He asks if he can sit at her table and she seems okay with that but otherwise ignores him. She's here for the music, not to be picked up by some random guy she's never met. But when a mysterious woman approaches and says something sternly to Mora in (untranslated) Greek, she makes a hasty exit. Johnny gives chase and despite again being rebuffed, he cajoles Mora into letting him walk with her and talk to her for a while. By the time they reach her apartment – which it turns out is on the pier above an indoor merry-go-round – they appear to be on friendlier terms. Johnny pushes Mora to invite him in but she declines, but when he asks if he can see her again she offers to make him breakfast if he comes back tomorrow. It's an offer Johnny accepts with all the suppressed delight of a teen who has just landed his first ever date.

When Johnny returns the following morning, the merry-go-round is just opening up and he strikes up a conversation with its genial owner (Tom Dillon), whose granddaughter Ellen (Luana Anders) takes a bit of a shine to this good-looking young visitor. When Johnny reveals that he's here to see Mora, however, the owner's cheery demeanour falters as if troubled by the news. Is he just being protective of a friend? Hard to say. A breakfast of freshly procured herring is served on a balcony whose view of the sea and the beach makes it one I'd be prepared to fight giant crabs with only a whisk for protection to be able to wine and dine on every morning. Here Mora tells Johnny that she makes a living posing as a mermaid in one of the pier's sideshows, and Johnny reveals that he joined the Navy to see the world after the death of his mother, to whom he was devoted after his father left them when he was young. "But I haven't seen any of it yet," he confesses. "You will," Mora assures him with an assurance that almost suggests she is able to read his future. Later, an elderly clairvoyant uses Tarot cards to do just that, and warns of a rather different fate. Mora then demonstrates her professed affinity with the sea and its creatures by grabbing a passing seagull and stroking it as you might do a pet. By this point it's hard not ignore a nagging sense that something is a little off here. But what, exactly? Mora then introduces Johnny to Captain Samuel Murdock (Gavin Muir), a jovial former English sailor who now runs the mermaid attraction in which Mora stars. While Mora gets into her costume, Samuel tells Johnny that he found Mora on an island back when he captained a ship of his own. "You know, you might be interested in that story," he adds, "It's a very unusual one," and then he invites Johnny to drop round and see him sometime. Johnny then pops in to see Mora in her costume and the effect is entrancing, enhanced by the illusion that she is lying underwater. At least we have to assume it's an illusion. That's certainly what Mora told Johnny earlier. I mean, mermaids aren't real, are they?

On their next date Mora says a little more about her background as an orphan on the Greek island of Mykonos and her relationship with Samuel, who adopted her and has been like a father to her since. As her relationship with Johnny strengthens, however, further signs that all is not quite right with her begin to emerge. A second appearance of the strange woman from jazz club causes Mora to faint while dancing on the beach that evening. Ellen then warns Johnny that Mora's two previous boyfriends both mysteriously disappeared and their bodies were discovered when they washed up on shore, cases that Police Lieutenant Henderson (H.E. West) is still investigating and still suspects that Mora had something to do with. Both Samuel and eccentric clairvoyant Madame Romanovitch (Marjorie Eaton) warn Johnny that he's in danger, and Samuel even hints at the nature of the threat with talk of mermaids and sirens leading men to their deaths. Everything seems to point to the somehow fantastic notion that there's more to Mora's relationship with the sea than her fondness for seafood and friendliness with gulls. Surely not...

All of this might sound like the premise of a Roger Corman style exploitation cheapie (as it happens, Corman was instrumental in helping to raise the film's meagre budget), but many of Harrington's previous short films were not rooted in horror but the avant-garde (they're included on the second disc in this set), working alongside Kenneth Anger, in one of whose films – Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) – he also acted. Yet he was drawn to genre filmmaking by his fondness for the classic Universal horror movies of the 1930s and the low-key atmospheric chillers produced by Val Lewton, notably the 1942 Cat People, to which Night Tide bears a number of structural similarities. It also shares Lewton's preference for subtly suggesting rather than explicitly stating, which helps to build a palpable sense of threat and mounting menace whilst keeping us guessing about Mora's true nature and whether we are watching a horror movie or a psychological thriller. And I'll come right out and admit that until the final scenes I found it impossible to make a decision either way.

In being made outside of the studio system the film was helping to break new ground, and tonally feels unlike almost any other American film of the period. This is partly due to the casting of the 24-year-old Dennis Hopper in his first lead role, and, strangely enough, to Harrington's lack of experience with actors. Hopper apparently helped the director with the cast but as a student of The Method was also free to play Johnny in a less 'performed' manner than he would likely have been allowed to under more experienced direction. This results in an interesting mixture of acting styles, with the more rehearsed performances of the supporting cast counterpointed by Hopper's easy naturalism and small improvisations. The two styles should clash but they never do, in part because Hopper's approach so effectively captures Johnny's outsider status and his hesitance, false bravado and growing uncertainty. It's a fascinating and impressively low-key performance peppered with interesting tics that always feel truthful, both to the character and the situation at hand. And he's in good company. Linda Lawson is suitably haunted as Mora, American-born Gavin Muir is convincingly English as Captain Murdock, Marjorie Eaton is just the right side of dotty as Madame Romanovitch, and famed occultist Marjorie Cameron (credited here only by her surname), is effectively creepy as the mysterious woman. Best of all, however, is Luana Anders, who subtly conveys Ellen's instant attraction to Johnny with a quick but perfectly timed smile and whose warnings about Mora seem to come from a place of genuine concern rather than jealousy. When Johnny later confirms that he has fallen for Mora, Ellen's accepts this and is even supportive, and the news doesn't sour her view of him one iota. So sweetly genuine is Ellen than long before the halfway mark I wanted to pull Johnny aside and make him realise that he was letting a golden opportunity for genuine and probably long-lasting happiness slip through his fingers.

What really makes Night Tide stand out, however, are the offbeat but strangely effective touches and influences that Harrington weaves into the story and with which he textures the drama: Mora's bongo-beat, night-time beach dance that draws on cinematic depictions of voodoo ceremonies; the severed hand that Samuel keeps in a jar as a keepsake of his travels; the strong echoes of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in the captivating sequence in which Johnny follows the mysterious woman (who at one point even takes out a pocket watch to check the time in the manner of Lewis Carroll's White Rabbit); the Mexican child with a doll and a haunted expression who may or may not be who the woman has transformed into; the way the camera doesn't linger in Mora's old room at Samuel's house when Johnny enters it but instead seems to drift through the window and be pulled towards the sea. And this is just a small sprinkling of moments and scenes that subtly unsettle without explicitly stating that something is amiss.

Night Tide is a film that really dug its hooks into me. On my first viewing, the seemingly improvisational hesitance of its early scenes took a while for me to fully engage with, but by the halfway mark it really had my attention. The second time around I had no such reservations, and with the benefit of hindsight I understood from the off what Harrington was aiming for here, and by the third viewing I found myself reading secondary meaning into just about everything that the main characters said or did. I've since watched it again with my partner, whose curiosity was piqued by my rambling enthusiasm, and she hasn't stopped talking about it since. It's a hell of debut feature for a director who clearly deserved better than Hollywood was prepared to gift him, and in common with the sea to which Mora feels so strongly drawn, there's a lot more going beneath its captivating surface than first impressions might suggest.

Had I read the section in the booklet about the condition that the original 35mm camera negative was in when it was acquired by director and film collector Nicolas Winding Refn I'd have been steeling myself up to make some serious allowances, but despite these early problems, the result of the meticulous restoration is downright lovely. Detail is sharp, the monochrome contrast is beautifully graded and try as I might, I couldn't see any trace of the former damage and wear that so horrified the restoration team when they first saw it (a fine grain preservation copy was used to replace the irreparably damaged sections). These people really are magicians. The film is framed in its original 1.66:1 ratio and has been stabilised so that there is no movement in frame, and an organic level of film grain is visible throughout.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also clean of damage, fluff or background hiss. The dynamic range is unsurprisingly narrower than you'll find on a more modern film or a big-budget studio production of the day, with little in the way of bass and a slight treble bias to the dialogue, but this is par for the course for a low-budget film of this vintage and it's otherwise fine. The music is in particularly good shape.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

DISC 1

Audio Commentary with Curtis Harrington and Dennis Hopper

Apparently sourced from an earlier laserdisc (that should help those in the know to date it), this archive commentary with director Curtis Harrington and leading man Dennis Hopper is a hugely valuable and enjoyable inclusion. Both men clearly held the film in high regard and enjoyed the process of making it, it being Harrington's first time directing actors and Hopper's first taste of low-budget independent filmmaking, which was in its infancy in America at this time. Harrington seems to recall more about the shoot than Hopper (though given Hopper's years of heroic substance abuse, this is hardly surprising), but both have engaging stories to tell, and there are some welcome details about the filming of individual scenes and some of the creative budget workarounds taken. Both praise the work of the cast, except for H.E. West as Lieutenant Henderson, whom Harrington had no hand in casting and whose line delivery on his first appearance prompts Hopper, with good reason, to say simply, "He's awful." Not for the last time in the special features, Harrington cites the influence of Val Lewton and Josef von Sternberg, and Hopper recalls that on the last day of the shoot he got hopelessly drunk and ended up in hospital after a serious motorcycle accident. A most entertaining listen and particularly valuable, given that we have since lost both of the talented contributors.

Audio Commentary with Tony Rayns

Rayns kicks off by stating that this is going to be a different sort of commentary to the ones he usually delivers, yet for me it was pretty much business as usual, which in Rayns' case means a commentary packed with facts about the film and its makers and fascinating analysis of individual elements. He provides detail on how he became acquainted with Harrington through his college friend Robert Mundy, whose later fall from grace is also intriguingly outlined. He looks at the genesis and production of the film and Harrington's early work alongside his contemporary Kenneth Anger, and even outlines some of the ways in which the film differs from the Harrington-penned short story on which it is based (in the story, for instance, Mora killed and cooked the seagull). There's so much in here. An excellent companion to the film, as ever.

Harrington on Harrington (24:38)

An archival interview with director Curtis Harrington, who responds to unheard questions about his career and how he first fell in love with film as a medium. His early experimental shorts get some coverage, as does his time living in Europe and working at Paramount on his return to America. I did smile when the first thing he says about the 1971 What's the Matter With Helen? turns out to be, "What's the matter with Helen is that she's crazy!" and was intrigued by his claim that all of his films are tragedies, something he believes American audiences resent.

Sinister Image: Curtis Harrington (57:05)

Two episodes from the video series featuring film historian David Del Valle's in conversation with key figures from cult cinema, both of which features amiable chats with director Harrington about his career. There is some overlap with other extras here, particularly the Harrington on Harrington interview detailed above, but Del Valle is an enthusiast for his subject and asks good questions, and there's solid coverage of Night Tide and interesting stories about working with Simone Signoret (on Games) and Shelley Winters (on What's the Matter With Helen? And Who Slew Auntie Roo?). Harrington also comments on some photos taken on various films during the course of his career that are displayed on screen.

Theatrical Trailer (2:17)

"Night Tide, with its boundless power ties these two together in a love tainted by strange, sinister terror." Sorry? Not a particularly persuasive sell, though it does avoid major spoilers despite using footage from later in the film.

Image Gallery

18 screens of promotional photos and posters.

DISC 2: CURTIS HARRINGTON SHORT FILMS

The films here can be watched individually or played automatically in sequence. All have optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired.

The Fall of the House of Usher (1942) (9:59)

Made on 8mm by Harrington when he was just 14 years of age, this visually primitive but still interesting work was clearly shot with an understanding of editing in mind. According to Harrington's memoirs, the film was originally shown synchronised to a recording of The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Kahn by Charles Griffes, but details of the recording and how it was used have been lost, so it is presented silent here. The occasional home-constructed title card is used for dialogue in the silent movie manner, but a familiarity with the specifics of Poe's original story will really help you make sense of what unfolds. The young Harrington also plays both Roderick and Madeline Usher, but probably could have done with some supplemental lighting – some sequences are almost pitch-black, but he still shows an early command of film form and he even built a cardboard model of the Usher house to burn down at the end. Intriguingly, this finale differs from the original story (where the house splits in two and collapses after the visitor departs) in a manner that was also used by Roger Corman for the climax for his own take on the tale twelve years later. Considering when it was made and on what format, it's frankly surprising (but most pleasing) that we can see this at all.

Fragment of Seeking (1946) (13:42)

The influence of Jean Cocteau and early Luis Buñuel is clearly visible on Harrington's first experiment with avant-garde filmmaking. It's something that Harrington was open about in his memoirs, though he also claimed not to have seen the very films from which he drew inspiration and that he'd only read about them at the time (and, I'm guessing from this film's visuals, he'd seen a few stills). Harrington himself plays a young man who enters a courtyard and is drawn to an emotionally distant and blonde-haired woman, but when he finally gets her alone events take a sinister turn. A semi-surrealistic mood piece with a horror story twist, one that kicks off with a moment that prefigures a key scene in The Shining. This is the first of three films here in which men are lured to potential doom by siren-like women, also a prominent theme in Night Tide. This was Harrington's first 16mm venture.

Picnic (1948) (22:19)

A family slowly makes its way down to a beach for a picnic on what may well be the windiest day of the summer. Once they are settled, the adult son becomes fascinated by a distant figure of a woman in white who is dancing on the shoreline, and when he follows and finds her, a whirlwind romance leads rapidly to tragedy. The siren mythology is more clearly evident here than in Fragment of Seeking and the surrealism is more inventively realised, with the son scaling a cliff face by that is shrunk in size by its distance from him, and halted in his pursuit of the girl because the steps he is climbing become as steep as a ladder, an effect achieved simply by titling the camera. It also has a splendidly unsettling ending.

On the Edge (1949) (6:12)

A middle-aged man walks onto mudflats and discovers a woman sitting in a rocking chair and going through the motions of knitting. He seems fascinated by what little she seems to have created, but his subsequent actions come at a price. A short film made to make use of an interesting location, one in which Harrington's parents play the lead roles, and his father had the sort of face that camera close-ups adore. In case you hadn't guessed, the siren mythology once again appears to have been an influence on the whisper-thin story.

The Assignation (1953) (7:31)

A masked and black-robed man boards a gondola and rides the canals of Venice in order to take a single red rose to the woman of his affections. Had this not been made in 1953 I'd have sworn there was a Jean Rollin influence on its visuals, particularly the figure of the masked and robed man and the atmospheric European setting. A mood piece that grew out of Harrington's love of Venice and the impact of his first trip on its Grand Canal.

The Wormwood Star (1956) (10:01)

Marjorie Cameron, who plays the mysterious woman in Night Tide, reads "knowledge and conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel" (I genuinely don't know what that is, but that's how it's described in the nicely drawn opening titles), while the camera frames her in disorientating fashion and drifts inquisitively over her paintings, which Harrington admits are what the film is really about. The paintings themselves, in which human, animal and mythological forms seem to be interchangeable, are genuinely fascinating, and the film itself is hypnotically scored by Philip Harland and Leona Wood.

The Four Elements (1966) (12:39)

If you watch the previous films and then go into this one without reading anything about it you're likely to need a little time to adjust. A documentary film about American manufacturing made by Harrington for the United States Information Agency after Night Tide failed to land him the studio feature directing gigs he had hoped for, it for the most part follows the format of such films (complete with shots of industrial workers and a sober narration), but makes interesting use of music and sound and almost semi-abstract close-ups of materials and machinery.

Usher (2002) (36:42)

Bringing his career full circle, Harrington's final film was a modern-day update of the very same story on which his first 8mm short was based, with the director again casting himself as both Roderick and Madeline Usher. By then in his 70s, Harrington was a better fit for Roderick Usher than he was as a young teen and he plays him well, though his age does give his portrayal of Madeline a slightly drag-act quality. He nonetheless makes this work for the film's centrepiece scene, a masked dinner party that has a distinct Queer Cinema vibe and more than a dash of the surrealism of his earlier works. He also includes a nod to director James Whale, one of the first openly gay directors in Hollywood and with whom Harrington was good friends, by having Usher offer his visitor gin and then proclaim, "It's my only weakness," a line famously spoken by Ernest Thesiger in both Bride of Frankenstein and The Old Dark House.

Also included on this second disc is an Image Gallery featuring 74 screens (well, nearly – a few of them are section title cards) of stills taken on the locations of several of the short films, plus some portraits of Curtis Harrington and even some scans of his family album.

Booklet

Indicator's booklets are always a treat, but some are so packed with worthwhile content that the term 'booklet' seems to be somehow selling it short. This is one of them, running as it does for a substantial 76 pages, all of them worth reading. First up is a reproduction of Edgar Allen Poe's poem Annabelle Lee, from which the film takes its title whose final verse is quoted in a caption at the film's end. After this we have the main credits for the film, then a chaptered essay by Paul Duane that discusses Curtis Harrington (including a collection of gathered trivia about his film career), Dennis Hopper, Marjorie Cameron, Harrington's television work, and his final years. Next we have a substantial extract from Harrington's posthumously published memoir, Nice Guys Don't Work in Hollywood, in which he looks back at the making of Night Tide, some of which is also covered in the on-disc extras, but Harrington goes into far more detail and shares more anecdotes here. Then there are extracts from a piece written by Harrington in 1952 for Sight & Sound examining the history of the 'fantastic' horror film from its earliest days to the genre's decline in the post-WWII period, with particular emphasis on Jacques Tourneur's Cat People and Carl Dreyer's Vampyr. Extracts from three contemporary critical reviews from British publications are followed by details of each of the short films included on Disc 2, complete with comments on each by Harrington from his autobiography. Next is a 1948 piece from Hollywood Quarterly looks at the work of Creative Film Associates in distributing the avant-garde shorts of the day, including the works of Harrington and Kenneth Anger, and a detailed account by Harrington of the making of Picnic, which appeared in the same publication the following year. Harrington's final contribution comes in the form of a statement made in 1956 whilst working on The Wormwood Star and expressing his growing disillusionment with the experimental film scene. Bringing up the rear are two pages devoted to the restoration and presentation of the feature and the short films, and the booklet itself is illustrated with photos of Harrington at work, at play and with friends, including one taken with James Whale in Paris in 1952.

Also included are 5 Postcards featuring front-of-house stills.

A film I was only vaguely aware of when this release was first announced and that I was unsure how I would respond to, but which I quickly found myself captivated by. It's a work that genuinely seems to get better with every viewing, as familiarity with the characters and story beats seems to open up new layers of meaning and influence, which I've only given a small flavour of above as discovering them yourself is part of the fun. If you're going to showcase a filmmaker's cult debut feature then this is how you do it, with a sparkling restoration of the film itself, a raft of excellent special features and a second disc full of short films that, as well as being fascinating in their own right, also allow you to follow the artist's journey from avant-garde experimenter to feature director. It's early days yet, but I can already see this reserving a place on my favourite disc releases of 2020. Unreservedly and enthusiastically recommended.

|