| |

"Growing up with a fascination for the macabre, I sat up alone watching every horror film that turned up on late night TV. My education included the Universal horrors of the 1930s and 40s and Jacques Tourneur's haunting collaborations with producer Val Lewton. But it came as a revelation to discover that not all tales of horror are set in some vague eastern European locale or on a remote exotic island, and they could be even more frightening when they take place in your own backyard." |

| |

Josephine Botting – Why I love… Night of the Eagle* |

Fans of the ghost stories of M.R. James – and what serious reader of horror fiction isn't? – will doubtless be well aware of his favourite narrative, where a scholarly sceptic is forced to reconsider his disbelief when confronted by a terrifying supernatural event or apparition. It's at the core of many of his finest stories, as well as the two most celebrated film adaptations of his work, Jacques Tourneur's Night of the Demon (1957) and Jonathan Miller's Whistle and I'll Come to You (1968).

Night of the Eagle is certainly in the M.R. James mould but was actually based on the 1943 novel Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber Jr., a book I must confess to still not having read. Whether Leiber himself was influenced by James I'm not in a position to say, but various sources note the influence of both H.P. Lovecraft and Robert Graves on his earlier work and Carl Jung on his later writings, and a recurring theme in his stories involves paranormal activity in modern urban settings rather than the gothic isolation of more classic horror fiction. Widely regarded now as a classic work of horror fiction and a 2019 Retro Hugo Award winner, Conjure Wife has to date been the subject of three film adaptations, with Night of the Eagle preceded by the 1944 Weird Woman and followed in 1980 by a more light-hearted take on the story, Witches' Brew.

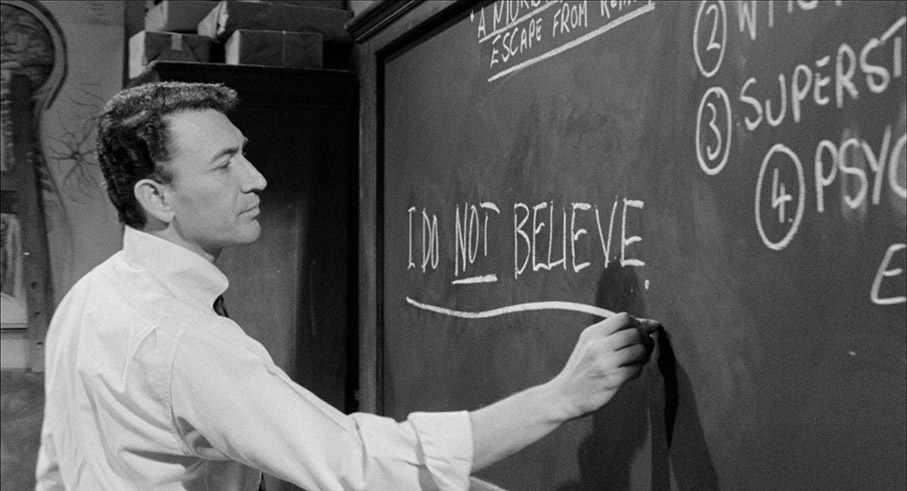

Night of the Eagle takes its subject seriously and lays out its credentials in the opening shot – the very first words of dialogue are "I...DO...NOT...BELIEVE!" emphatically stated by Professor Norman Taylor (Peter Wyngarde) of the Hempnell Medical College as he writes this mantra on the classroom blackboard in large capital letters. These four simple words, he informs his students, are the best defence against all of the superstitious nonsense out there that are getting in the way of hard scientific fact. He's absolutely right, of course, but this is not real life but a horror tale, and we thus know he's setting himself up for a dramatic about-turn in the not-too-distant future.

At this point, things are going swimmingly for Norman. His students get the best grades in the school, and it looks like he'll soon be up for a promotion. He lives in a nice house, drives a sporty convertible, and his attractive wife Tansy (Janet Blair) adores him. Not everything in Norman's life is picture-book perfect, however. One of his students, Margaret Abbott (Judith Stott), has a serious crush on him, which irritates the hell out of her jealous and underachieving boyfriend Fred Jennings (Bill Mitchell). Yet even this fails to seriously bother Norman, who responds by putting Margaret in her place and ordering Fred to pull his socks up. There's also some envy amongst the wives of the other professors, who regard Norman as the new kid on the block and believe that their husbands are more deserving of the promotion than him. Despite this, several of them meet with Norman and Tansy every Friday evening to play bridge, the very picture of a cosy and pleasant little academic community.

This particular week the evening is hosted by the Taylors, and after their guests have departed Tansy becomes unusually agitated and starts urgently searching the living room. When questioned by Norman, she claims she's lost a shopping list on which she has written the phone number of a dressmaker she wants to use, but her determination and clear concern suggest that it's something more important than that, and if she's telling the truth then she's looking for the list in places that it couldn't possibly be. She continues her search after Norman heads upstairs and returns downstairs after he has gone to sleep, and when she eventually finds what she has been seeking, she immediately picks it apart and burns it. What is it? Ah, you'll have to see for yourself.

While his wife is preoccupied, Norman is upstairs in the bedroom looking for his pyjamas, but the drawer in which the clean ones are stored is frustratingly jammed. When he finally frees it and removes it from the cupboard he finds a small jar buried within containing a dead spider. A BIG dead spider. As you might imagine, he has a few questions about this for his wife. He has many more the following day when he discovers that this is not the only strange artifact that Tansy has hidden around the house. When pressed on this, the clearly rattled Tansy reveals that it all stems back to a trip that they took to Jamaica and a witch doctor they met there who brought a young girl back from the dead before their very eyes, or at least that's how she remembers it. She's been practicing witchcraft for years, she tells him – why else did he think he was leading such a charmed life? Outraged by his wife's devotion to such superstitious nonsense, Norman destroys every last magical object in the house, despite his wife's pleas. "I will not be responsible for what happens to us if you make me give up my protection!" she cries, then flies into a complete panic when Norman accidentally burns his own photo. There's clearly more than career enhancement going on here.

From this point on, Norman's good luck all but evaporates in a nicely judged mix of earthly problems and something more supernaturally inclined. It's in the latter that the film really flexes its cinematic muscles, notably in an excellent sequence in which the Taylor house comes under assault from an unseen force, its power and malevolence suggested entirely by the lighting, camerawork and sound effects. It's a scene that scared me witless when I first saw it in my youth, and even all these years later, with umpteen horror films under my belt, it still sends chills up my spine. There are plenty of shots suggesting the physical form that this force will ultimately take, and the real surprise is how convincing it proves to be when we actually get to see it. This proves to be Night of the Eagle's trump card, that it successfully sells its witchcraft as real and its consequences as genuinely threatening. It's a rare trick managed only by a select few – that the two most celebrated examples are Night of the Demon (1957) and The Devil Rides Out (1968, another highly regarded novel adapted for the screen by this film's co-screenwriter, Richard Matheson) is only appropriate, given that Night of the Eagle bears a structural and visual resemblance to the former (the similarity in title is surely no coincidence) and has the latter's breathless, incident-packed pace.

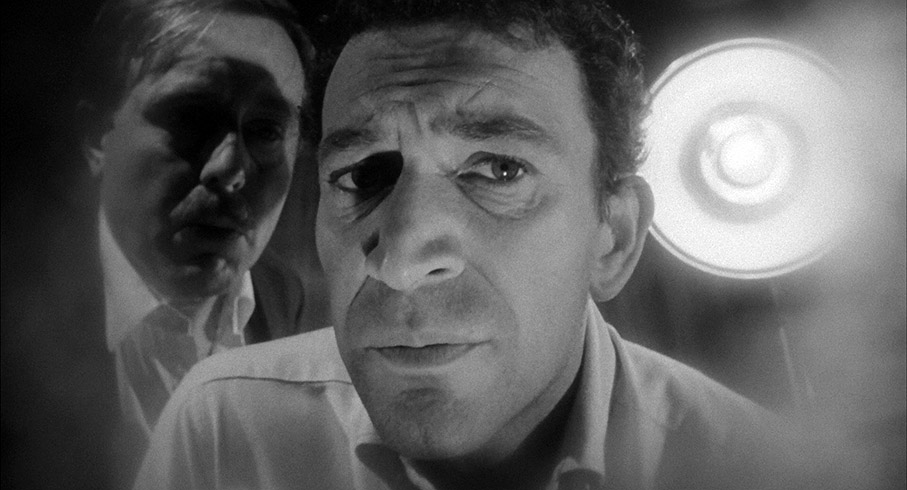

Now if any or all of this sounds a little hokey then let me assure you that it never plays that way. Right from the start, director Sidney Hayers treats the story as seriously as he would an earnest relationship drama and has clearly instructed the cast to follow his lead. As Norman, the always authoritative Peter Wyngarde is perfect casting as a no-nonsense, self-assured sceptic who is determined to confront and combat superstition wherever he finds it, and his subsequent battle of wills with his wife is both tense and believable. Crucially, he's every bit as convincing in his later terror when faced with the manifestation of the forces that Tansy has been trying to keep at bay. In that reverse-belief approach horror movie fans have to apply to their beloved genre, you know that he's talking perfect sense in those early scenes, but also that – within the context of the film, at least – he's absolutely and dangerously wrong. Watching the film some years ago with my partner, I was amused when she yelled at the screen, "Why do men never listen?" No comment.

Having already carved a successful career in Hollywood, where she was known primarily for comedies and musicals, Janet Blair here proves her metal as a dramatic actress, from the authentic urgency of her living room search to her horror at a potentially deadly mistake that Norman unknowingly makes when he accidentally burns his picture, and her palpable fear at what this threatens to unleash. But my favourite performance comes from Margaret Johnston as Flora, the wife of Norman's colleague, Lindsay Carr (Colin Gordon), but to get into the specifics of why will drag me into spoiler territory, so if you'd rather not know more, I'd hop ahead to the next paragraph. Right from the moment we first meet her there's something a little off about our Flora, and it thus makes sense when it's revealed that she is employing the very same conjure magic that Tansy has used to protect Norman in an effort to bring him down. Where Johnston shines is in her ability to project Flora's oddness in a way that, on a first viewing at least, does not come across as overtly suspicious. Whether it is the way she looks around Tansy's kitchen during their evening bridge meet, the overly enthusiastic smile she flashed when responding to Tansy's remark-triggered clumsiness, or her expression and posture when being driven to the Taylor house by her resentful friend Evelyn (Kathleen Byron), she comes across not as malevolent but as a woman whose limp and behavioural tics I'd initially put down to a medical condition. Only on a second viewing are these intriguing character moments shown to me more than just engaging bits of business, and when the truth comes out, they are not abandoned but threateningly amplified.

The tightly plotted and consistently intelligent script by frequent collaborators Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont – with contributions from crime writer George Baxt – together with the excellent performances and Sidney Hayers' smart and inventive direction are all crucial here, with Norman's transformation from hardened sceptic to desperate believer an object lesson in how to make such a switch of belief convincing. Technically, the film outshines its doubtless limited budget through Reginald Wyer's fine monochrome cinematography, Ralph Sheldon's sharp, fat-free editing, and some surprisingly convincing visual effects – there's a road crash here that's as alarming as any I've seen in a movie of this vintage, despite being created largely through editing and what I presume is back-projection.

For years it's been a complete mystery to me why Night of the Eagle does not get discussed in the same breath as its more widely celebrated contemporaries, and the fact that it has been selected for a 4K remaster by the good people at Studiocanal – and is being so well reviewed as a result – suggests that I'm not alone on this score. It stands up handsomely even all these years later, in no small part because it's built on a such a strong foundation and because everyone involved takes even the more fantastical elements as seriously as they would a prestige drama. The result is a horror tale that is consistently involving, often exciting and sometimes genuinely tense, a work urban witchcraft horror that predates this subgenre's cheerleader Rosemary's Baby by six years, and rewards rather than insults the intelligence of the viewer.

The result of a new 4K restoration (unfortunately I have no more details than that), the transfer on this new Studiocanal Blu-ray represents a significant leap over the previous Optimum DVD. For a start, it's in the correct aspect ratio of 1.85:1 rather than the screen-filling 1.78:1 of the DVD, but the real prize here is the quality of the image, whose detail is sharply rendered and whose greyscale contrast is sublimely graded, allowing for strong but not detail-swallowing black levels, cleanly rendered highlights, and a generous tonal range between. A very fine film grain is visible throughout, and if there are remaining dust spots of traces of any former wear, I must have missed them. If there's a downside to the image clarity here – and it really is a minor one – it's that a tether used to encourage the eagle of the title to fly towards the camera is now clearly visible in one shot. Given how terrific that sequence is as a whole, that's easy to live with. The disc is encoded for region B only.

The mono soundtrack is presented here as Linear PCM 2.0, and is also in robust shape, with clear presentation of the dialogue, the eerie sound effects, and William Alwyn's lively score, although the slight tonal range restrictions do mean that the louder notes of music can be a tad shrill if you have the volume of your sound system cranked up. Otherwise, no complaints, and there is no trace of wear or damage here.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Screenwriter Richard Matheson

Now this is a rare treat, a commentary by late, great novelist and screenwriter Richard Matheson, and while there is no indication on the disc where this was sourced from, Matheson's own comments date it as having been recorded in 1995 for a US laserdisc release under the American title of Burn, Witch, Burn. There are a fair few pauses here, but none are of inordinate length and are rendered irrelevant by what you get in return from a writer of Matheson's stature. He outlines how he met co-screenwriter Charles Beaumont, how this particular project came about, how he works when collaborating with another writer (this is intriguing), and reveals that once he hands the script over he is almost never involved with the production, seeing nothing of the film until it is complete. "Usually, this turns out poorly," he admits, "but once in a while it turns out well, and in this case it did." He's guarded in his praise (several positive comments are preceded by the qualifying adverb, "quite"), but still has positive things to say about the direction of Sidney Hayers, composer William Alwyn's score, and actors Janet Blair, Margaret Johnston and Peter Wyngarde, the last of whom he admits to never having seen in anything else except Jack Clayton's The Innocents (1961). He also takes a fair few diversions to talk about his screenwriting career, including his positive experience working with Roger Corman on three of his Edgar Allen Poe adaptations, and notes that the only actor who ever changed a word of his dialogue was Peter Lorre, with whom he worked on The Raven and The Comedy of Terrors(both 1963). He's open in his praise of Fritz Leiber's 1943 source novel, Conjure Wife, which he describes as "a classic" and "so complete" (I really must read it), and as the film draws to a close, he remarks that, "I haven't had much to say about this film because it speaks for itself, really." This is just a small sampling from a richly informative and welcome companion to the film from one of its key creators.

Burn Witch Burn: Anna Bogutskaya on 'Night of the Eagle' (24:35)

Critic, broadcaster, and author Anna Bogutskaya kicks off by admitting that she first saw Night of Eagle about three years ago when researching the presentation of witchcraft in cinema, and that she didn't know what she was expecting from the film, but that it wasn't what she got. She discusses the positive presentation of marriage dynamic in the film, explains why the sorcery that Tansy is practicing is conjure magic rather than witchcraft, compares her character with more typical presentation of witches in cinema of the day, and notes that in a flipside of the norm, it's the male lead instead of his female counterpart who ends up terrified and screaming at the climax. She also explores the notion that the career success enjoyed by the male characters may be almost completely down to their wives, and intriguingly wonders if this practice could be far more widespread than the single academic institution featured in the film.

Archive Interview with Peter Wyngarde (24:26)

An archive interview with a hat-and-shades wearing Peter Wyngarde, apparently conducted in 2015 to mark the first HD incarnation of Night of the Eagle. He claims to have initially dismissed the script as rubbish and tossed it out of the window, then decided to do the film solely to raise the money to buy a car he fell in love with on the very same day. He has nothing but good words to say about the production itself, however, praising the work of his fellow actors and director Sidney Hayers, and describing the shoot as a happy one. He also reveals that he attended the premiere with his fellow actor and then flatmate Alan Bates and an up-and-coming young director named John Schlesinger, only to discover that they were the only people in attendance. Pleasingly, he confirms that both he and Schlesinger were impressed by what they saw. He recalls introducing himself to the titular eagle and its one-eyed trainer, has a 'life imitating art' story about Janet Blair and her Hollywood home, and admits to not being fond of the American title. Towards the end, he tells a couple of stories about the filming of The Innocents, and does briefly touch on some of his other notable roles, including a personal favourite of mine in which he played the leader of the Hellfire Club in the delicious and once-banned Avengers episode, A Touch of Brimstone.

UK Theatrical Trailer (2:28)

A wild, borderline frantic trailer peppered with optical effects (the screen vibrates when the phone rings, for example), flashing imagery, animated graphics and titles, and urgent narration, explosively edited to some of the film's noisiest moments and music. The print here sports a fair amount of damage, but something this excitable is worth preserving, whatever the condition. Be warned, there are a couple of spoilers here.

US Theatrical Trailer (2:28)

A less hysterical US trailer for the film under its American title of Burn, Witch, Burn shows its sexist age in the captioned announcement that it stars the lovely Janet Blair and the dynamic Peter Wyngarde in a tale it describes as "a holocaust of terror!" There are a couple of major spoilers on full display here, and the animated, stylised and multi-font captions give it the feel of a Universal horror trailer from the 1930s.

US Alternate Opening Credits (3:55)

Oh boy. The opening credits for the film's American release under the title Burn, Witch, Burn are preceded by a 2 minutes and 20 seconds of black screen accompanied by a grimly narrated warning of the sort of demonic content and satanic incantations that are completely inappropriate for a film that contains neither. I actually snorted with laughter when narrator Paul Frees concludes a list of object used in witchcraft with, "charms, amulets, voodoo candles, grave dirt… and lots of hair." Those damned satanic hippies are at it again.

Behind the Scenes Stills Gallery (1:12)

A rolling gallery of 14 behind-the-scenes photos, including a couple revealing how specific tracking shots were filmed.

Also included with the release version of the Blu-ray are four art cards, which are basically hard copies of publicity stills for the film.

A personal favourite horror work from the 1960s – one that for my money stands up handsomely – is given the sort of treatment it deserves on this fine new Studiocanal Blu-ray (it's also been released on DVD, but I can't help thinking that would be doing the quality of the restoration a disservice). It certainly wipes the floor the previous Optimum DVD, in the quality of the restoration and transfer and some damned good special features (the earlier DVD had none). Highly recommended.

|