|

When I was in my second year at art school, our art history teacher set the class an interesting project. He split us into three groups and tasked each of us with recreating Pablo Picasso's iconic proto-cubist painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, completely from memory. If you know the painting, you'll doubtless be able to appreciate the difficulty of the task. This is not a realist work, and not only did we have to recall how many figures were in the image, but how they were positioned and – most complex of all – exactly how Picasso had abstracted them. It's a testament to the distinctive nature of this painting that all three groups produced surprisingly accurate approximations of it.

Picasso may well be the only twentieth century artist that just about everyone has heard of, regardless of whether they have seen any of his work. Of those who have, there are still a fair few who dismiss him and his prolific output as readily as they doubtless scorn almost anyone whose work falls under the pejorative umbrella of modern art. But to do so fails to take on board the impact that artists like Picasso had at a time when art really mattered. They found new and revolutionary ways of looking at the world, created movements whose influence can still be seen today in everything from advertising and fashion to architecture and film, and in the process redefined over and over again what could and should be classified as art. It's a rare thing indeed to be offered the chance to watch one of these pioneers at work, but that's exactly what Wages of Fear and Les Diaboliques director Henri-Georges Clouzot's 1956 documentary, The Mystery of Picasso does with mesmerising aplomb.

The film opens with the voice of Clouzot himself suggesting, a little misleadingly as it happens, that we can read what is going through the mind of an artist by observing what he does with his hands. On the evidence presented here, I'd argue that this is not actually the case. In the course of observing Picasso paint and draw during the course of the film, I'm not sure I'm any the wiser about his thinking behind them. What the film does vividly capture, however, is Picasso's technique, revealing in detail how he approaches the creation of an original artwork, and for anyone interested in art and particularly the work of Picasso, this is absolute gold.

Clouzot's approach is ingeniously simple. His camera is positioned behind a specially constructed easel, on which is fixed a frame of opaque material that allows ink to pass through it without distortion or smearing, with the result that anything drawn or painted on its surface can also be clearly seen on the other side. Thus, while filming the rear of the canvas (I know it's not actually canvas but the term still feels appropriate) means that the artwork itself is horizontally reversed – which may well have been corrected in post-production – it allows us an uncluttered view of the process of its creation, which unfolds on screen as if the image is animating itself into existence. Nor is it a purely visual experience, with the development of each painting accompanied by a different musical piece, all composed by Georges Auric (Roman Holiday, The Wages of Fear, Rififi) to compliment or counterpoint the imagery as it forms.

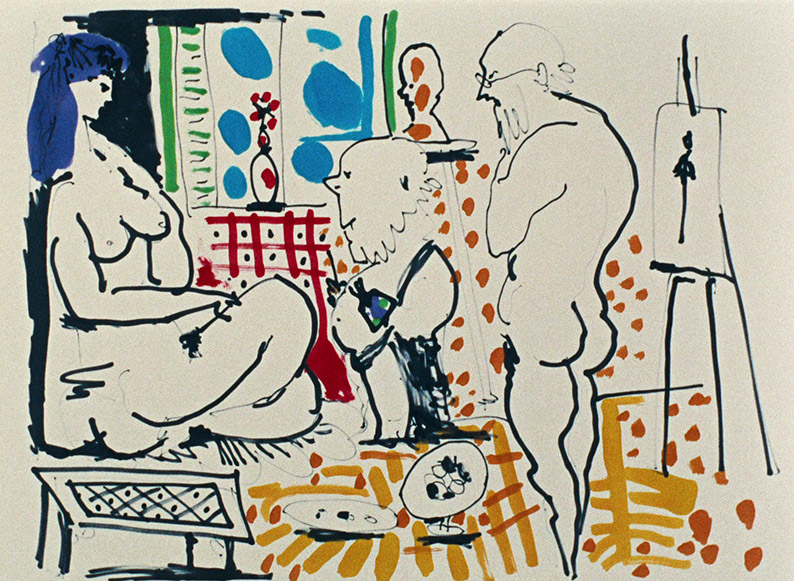

This proves a lot more compelling than it probably reads, with the development of each work creating its own narrative, as two seemingly abstract lines are transformed by a third into an instantly recognisable representation of a nude, a bull, a matador, or any number of Picasso's favourite motifs, and we're continually kept guessing about the final form that the artwork will take. Will it be realist, impressionistic or a cubist abstraction? And at what point will the artist himself consider it complete? Repeatedly, I found myself nodding in appreciation at what Picasso had created, only for him to add more and more detail, using this early minimalism as the foundation for a very different and far more complex picture.

What really struck me during the first half was the sheer assurance with which every ink stroke is made. There are no corrections or remotely hesitant moves here, making it clear that from the moment the pen or brush makes contact with the canvas, Picasso knows exactly how the seemingly improvised lines he is drawing will interconnect and fit into an as-yet undefined whole. Repeatedly, his often undiscussed skill as a realist (check out his early work if you're looking for evidence of this) and understanding of human and animal anatomy drives and underscores this approach, as a figure is defined in two or three quickly executed moves that in isolation would probably be thought of as abstract squiggles.

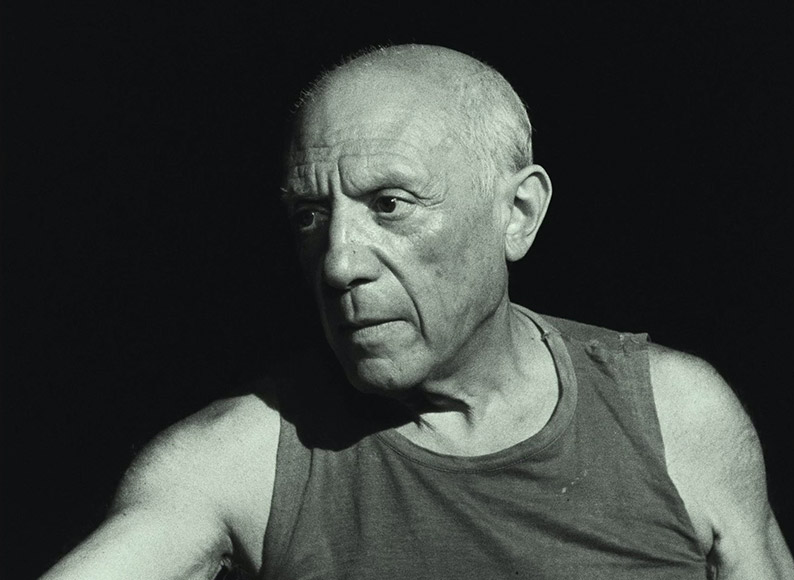

Then, 30 minutes in, the fourth wall is broken when this film about Picasso briefly becomes a film about the making of a film about Picasso, as the artist completes a piece and director Clouzot asks cameraman Claude Renoir (himself the grandson of a famous painter, of course) how much film they have left and Picasso if he is up for doing another picture, to which the then 75-year-old artist replies, "I can go all night if you want." It seems unlikely that this is the pure documentary footage it purports to be, given how carefully the scene is lit and that it is covered from a number of carefully chosen angles, but it certainly feels authentic – these men are not actors and their conversations have an engagingly naturalistic feel, and it's here we get a clear look at how the artistic process is being filmed.

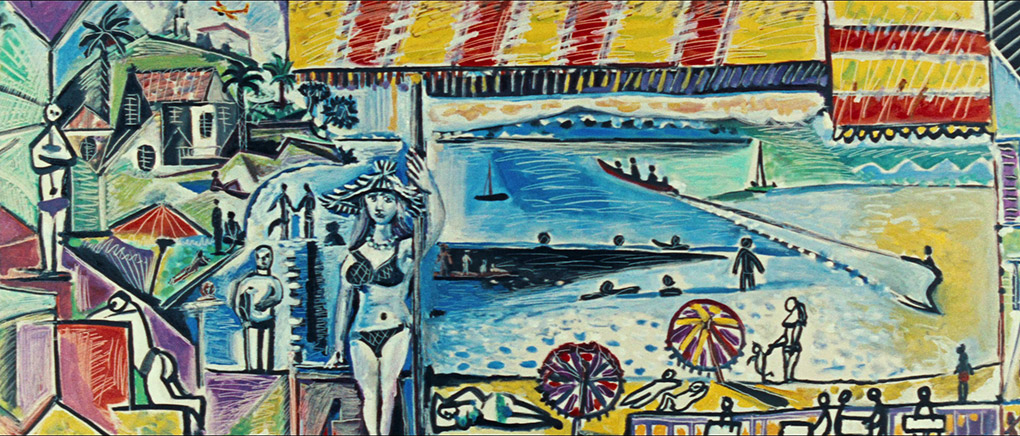

There's a similar break 20 minutes later, when Picasso joins Clouzot by the camera and suggests that he needs to take a different approach, to go deeper and reveal the different layers of his work. This requires a switch to oil paints and the abandonment of the live approach (the construction of the artworks now moves forward in stop-motion steps, a technique that has already been road-tested by this point), which ten minutes later prompts Picasso to ask for a larger canvas and the 1.33:1 framing to expand horizontally to CinemaScope. Here, the one-stroke assurance of the ink-based works is abandoned in favour of an approach in which the final form of the painting is realised through a process of continual experimentation and change. This proves both fascinating and intermittently frustrating, as an artwork comes together into a form that can feel complete, only to then be transformed as whole swathes of exquisitely realised detail are painted over, reformed or abstracted. This peaks in a final painting that initially has a proto-cubist picture postcard quality to it, but which undergoes so many, often drastic alterations that the final image bears only a passing resemblance to the one from which it has developed.

I'm guessing all this would all be a hard sell to those with little or no interest in art or the work of this singular creator, but they're likely to be warned off by the title anyway. But for those of us with a background in art or an appreciation of the pioneering and distinctive work of this most iconic of twentieth century artists, The Mystery of Picasso makes for compelling, revealing and artistically thrilling viewing. It may not really deliver on the promise of its opening monologue, but as a portrait of the artist and a study of his technique, it really has no peer.

Sourced from a restoration carried out by Le Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée, the transfer on this Arrow Academy Blu-ray here is first class, boasting robust contrast on the black-and-white live action sequences, and vibrant (but not artificially over-saturated) colour when it makes its way into the artworks. The image is sharp and the detail distinct, and the switch from 1.33:1 to 2.35:1 is subtly handled, with both aspect ratios maximising the screen space available. Dust spots have been removed (and if the restoration featurette is anything to go by, there were plenty), and the image is clean, free of damage and rock solid in frame. Very nice.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack betrays its age in its narrowed dynamic range, but in other respects is in very good shape, reproducing Auric's varied score cleanly and without distortion, while the dialogue scenes are clear and without any distracting background hiss and crackle.

Clear and optional English subtitles are activated by default.

A Visit to Picasso (20:24)

Winner of Best Documentary BAFTA award, Paul Haesaerts' 1949 film is effectively a silent movie backed by a music score and a prim English narration that usefully explores Picasso's early work and his development as an artist. The real meat of the film, however, is footage of Picasso in his studio in Vallauris, while in sequences that directly prefigure Clouzot's film, he is recorded painting on large sheets of glass positioned between himself and the camera.

La Garoupe (9:30)

A mixture of black-and-white and faded colour silent home movie footage, shot by Picasso's friend and contemporary Man Ray, of Picasso and friends holidaying near Antibes. Of interest primarily for the footage of Picasso at rest and at play.

Picasso, My Father (25:30)

In a newly filmed interview, Picasso's daughter Maya recalls growing up with her father and some specifics about the making of the film, which is illustrated with clips and some behind-the-scenes photos. She also provides some details of the inks and material used for the artworks created within the film, and in what will seem particularly out-of-step with the current discussion on exploitation within the entertainment industry, she suggests that Clouzot slept will all his lead actresses.

The Mystery of Picasso Restored (1:59)

Before and after comparisons of the restoration. On the evidence here, the restoration team must have had their work cut out for them cleaning and stabilising the source image.

Also included with the first pressing only is an Illustrated Collector's Booklet featuring new writing on the film by author and illustrator John Coulthart, but this was not available for review.

Definitely not one for those of a philistine bent, and while an appreciation of Picasso's work is not essential to get the most out of the film, I'm willing to bet that it helps. Personally, I can't think of another film that explores an artist's technique as captivatingly as Clouzot does here, despite (or perhaps because of) the technical simplicity of his approach. A fine transfer from a solid restoration is backed by a decent set of extras, particularly the Haesaerts documentary and the interview with Picasso's daughter Maya. I really like this disc. Highly recommended.

|