|

If you’re a regular visitor to this site, the chances are that you favour the offbeat and th e challenging over the comfortingly safe predictability of mainstream cinema. For you, I have a question. Have you ever been left scratching your head by a film that you found yourself strangely fascinated by anyway, one that lingered in your head for long after the end credits had rolled? I’m guessing that for many of you the answer is yes. Quite a feeling isn’t it? If this includes you, then Argentinean director Alejandro Fadel’s 2018 Murder Me, Monster [Muere, monstruo, muere] might just be up your street. Be warned, however, that it’s likely to frustrate as many as it enthrals, being a mystery to which the solutions are largely metaphorical, if indeed they are solutions at all.

It begins in grimly intriguing fashion, as the camera drifts inquisitively through a small herd of sheep and momentarily comes to rest on the legs of a slowly approaching shepherdess, who drops to her knees with struggled gasps of distress. As the camera glides gradually up to her face, we can clearly see that her throat has been cut. As her head lolls backwards, it looks set to separate itself from her body, something the shepherdess tries to prevent by grasping the back of her head and attempting to right it. As she does so, the sound of something monstrous can be heard nearby, something that she appears to be observing with a dying look of horror.

The image then cuts to black and fades up later after night has fallen on a wide shot of a mountain countryside dirt road, down which two police vehicles are unhurriedly driving, a slow pan that concludes when they reach the remote farm at which this atrocity has occurred. Inside the farmhouse, the Captain (Jorge Prado) interrogates an elderly, one-eyed farmer, whom he clearly believes is responsible for the murder. “Tell me,” the Captain asks, “where’s the head?” The farmer is initially unable to answer, but a sharp slap to the back of the head from an off-screen policeman prompts him to claim that he saw a stranger walking up toward a locally located refuge. “He looked lost,” he says. “He’s the one you want to ask where the head is.” At this point this statement means nothing to the viewer, but will soon be shown to be significant. The Captain isn’t buying it and hauls the farmer off to the station, leaving the wrestler-faced officer Cruz (Víctor López) to wait for the forensics team to arrive and to look around and see if he can find the missing head. Aha, I thought, that missing head is going to be one of the key puzzles in this story. Not so. A short while later, Cruz discovers the head lying in the mud next to a sleepy and presumably unhungry pig. Before doing so he examines the headless body, whose ragged neck wound seems to be seeping yellow goo, the first sign that this may be no straightforward homicide.

What follows is an object lesson in how to subtly deliver character information. Cruz picks up his phone and makes a call to a woman we later learn is named Francisca (Tania Casciani) to tell her that her husband has been seen in the mountains heading towards the refuge. He tells her that he’s asked for official permission to search for the man, but reveals that the snow is complicating things. “He’s probably dead,” he rather coldly adds, a statement he intriguingly follows with, “I thought that’s what you wanted to hear.” Instead, Francisca asks for his help, and he assures her that if he does this it will be for her sake only. When he rings off, his colleague Niño (Francisco Carrasco) mocks him for agreeing to look for the missing man. “It’s his problem if he wants to die,” he bluntly tells him. “It would solve everything for you.” Although never overtly stated, it’s clear from this brief conversation that Cruz is having an affair with the missing man’s wife, that he wouldn’t shed a tear if the man was to conveniently die on the mountain, that he cares enough about Francisca to help that very same man survive if she asked him to do so, and that his unsympathetic colleague is fully aware of their relationship.

Cruz is as good as his word and makes his way up the bleak and snowy mountain plain and the husband, whose name we soon learn is David (Esteban Bigliardi), sitting barefoot and uncommunicative in a long abandoned and isolated building. He dutifully returns him to Francisca and is emotionally hugged and verbally thanked for his efforts. Once inside, David mutters distractedly about the voices he hears, the specifics of which Francisca is unable to tease from him. She tells him that she’s run warm water or a bath and removes his shirt, revealing a large and alarming scar that runs the entire length of his spine. “Does it hurt again?” Francisca asks, tracing the scar with her hand, and action David stops when that hand begins sliding into his underwear. When the power cuts out, Francisca goes outside to restart the generator, and when she returns, the now naked David has made his way into the bathroom, where he collapses into a writhing, painfully gagging mess on the floor. Francisca immediately moves to tenderly comfort him, making it clear she really does care for his wellbeing, prompting me to wonder if Cruz’s attraction to her might be one-way. Apparently not, as a short while later, Cruz and Francisca are lying naked in bed, the edge taken off their post-coital relaxation by the solemn pall that seems to hang over everything Cruz says and does. Then Francisca asks him to dance for her, a request that he initially dismisses before slowly breaking into a gentle, solitary dance of writhing serpentine moves to a romantic song by Sergio Denis. It’s a performance that clearly delights Francisca and reveals a side of Cruz that remains otherwise buried beneath his hangdog looks and troubled demeanour, and an action we will see repeated at key moments of his character’s arc.

As to where the film goes next, well, once again I’m faced with the dilemma of how much plot to reveal without spoiling things for first-timers. If you want to go into the film reasonably cold, I’d quit here and skip to the final two paragraphs of this review (or click here to do so automatically), as I was certainly surprised by what happened just a few screen minutes after the above-described scene. If you’re game for a little more, then feel free to stick with me and I’ll add a further spoiler warning when I get to where the film goes – or where I think it goes – in its later scenes.

At this stage of the story I found it hard to be sure if the monster of the title (more on that in a minute) was an actual living creature or a metaphor for one, a supposition that is soundly dismissed when Cruz drives Francisca and David home that evening. As they near the abode, a sudden roar seems to physically impact the vehicle and spin suddenly to a halt, and the shape of what looks like a large, humanoid figure is briefly outlined by the dust that the skid throws up. As Cruz checks the truck for damage, David seems to sense the presence of something, only to be then nearly knocked off his feet by three darkly-dressed motorcycle riders. The vehicle is apparently unharmed, and as they reach their destination, David walks ahead into the brazier-lit darkness of the drive to their house, and after sitting in silence with Cruz for a short while, Francisca exits the vehicle and follows. As she approaches the house, however, an ominous sound prompts her to look around nervously, and seconds later she pulled to the ground and a tentacle wraps itself firmly around her neck. As she attempts to crawl away, the tentacle grips her throat so tightly that it begins to draw blood, causing her to contort her face in extreme pain and terror.

In an unexpected but economical time-jump, the film cuts midway through this shot to glum daylight of the following morning, as Cruz and his taciturn female colleague Sara (Sofia Palomino) stand over the headless body of Francisca, who is lying on the ground with her legs spread and her lower body exposed. Cruz is clearly in shock, and the look that the clearly disturbed Sara throws him suggests she is also aware of his relationship with Francisca. The comforting hand that the Captain lays on his shoulder a short while after makes it seems likely that he is too. It quickly becomes clear who the Captain believes is responsible when Niño hauls the naked David outside, throws him to the ground and presses his face into the mud with his boot. “Where is the head?” the Captain demands of the shaken and uncommunicative David. This time, a search fails to turn up anything, and when Cruz visits the morgue, the coroner coldly tells him that “the guy beat her and fucked her hard. With a stick, maybe.” David is subsequently confined to a psychiatric institution, where he is interviewed by a psychiatrist (Romina Iniesta), to whom he talks obliquely about a controlling voice, “a linguistic attack” that makes him violent, not physically, but inside. When the psychiatrist suggests that they talk about the monster, however, David gives a small but fearful shake of his head.

This can’t help but re-awaken the notion that the monster committing these crimes is one that dwells inside the mind and body of a deeply disturbed man, which itself would suggest that the attack on Francisca that we witnessed was not how the assault actually occurred but how it played out in David’s troubled mind. Yet neither of the first two arrested men seem to fit the profile of a strong and savage killer. The farmer who was initially accused of the first murder was old, frail-looking, and blind in one eye, while David is borderline emaciated and seems to lack the strength to even walk with any confidence, let alone decapitate a woman who loved him dearly. By this point in the story he has become the prime suspect for both murders, having also been seen and ultimately located in the vicinity of the first. When the body of a third decapitated woman is later found, the fact that he has by then escaped from the psychiatric hospital sees the case against him further grow. But what of that yellow goo that Cruz discovers on the wounds of the first and third victims, a sample of which he captures in a jar that he intermittently opens and smells, as if seeking some strange guidance from it? Even more concrete evidence of a monstrous physical threat is discovered when Cruz visits the morgue and examines the head of the first victim, and finds a large, sabre-like tooth embedded in the skull just behind the left ear. There’s definitely something out there, but what?

This may sound like an intriguing setup for a creature feature in the traditional American indie horror mode, but there are a couple of sound reasons why the film has frustrated and annoyed as many as it has compelled. The first is the pacing, which kicks against the horror movie norm by playing out at unhurried tempo that never shifts gear, regardless of what is infolding on screen. For those raised on the rapid-fire editing speed that of current Hollywood cinema, as well as genre fans used to a slam-bang final act, this will require some serious adjustment and patience. This, coupled with a use of locked-down shots, slow zooms and glacial pans, and borderline philosophical conversations that unfold between characters who keep their emotions in check, has seen a fair number of the film’s detractors describe the film as boring. I beg to differ. As someone who generally responds to the trend for rapid pacing over meaningful content with a muscle-stretching yawn, I’m always relieved to find a film that is willing to ease off the accelerator and take its time. That the tempo and tone set by the opening sequence never significantly alters may confound initial expectations and genre convention, but so effectively is this approach defined in those early scenes that I quickly acclimatised to Fadel’s deceptively minimalist approach. And there’s more going on here than the slow-moving surface may initially suggest, with conversations that initially seem to be more about the characters than the story later shown to have unexpected significance on narrative development and whole sequences stripped of all but the bare essentials. This approach allows Fadel to focus instead on building an almost overpowering sense of mysterious dread, a task in which he is aided significantly by Julián Apezteguia and Manuel Rebella’s moody digital scope cinematography, Alex Nante’s disconcerting score, and Santiago Fumagalli’s terrific sound design. This focus on atmosphere and location has seen comparisons drawn with Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s 2011 Once Upon a Time in Anatolia [Bir Zamanlar Anadolu'da], another slowly paced crime story that unfolds in an isolated rural location. The two films certainly share some DNA, but where Ceylan’s film developed into a reflective character-centric drama, Fadel’s moves into altogether stranger territory.

Adding to the problem for some is the film’s refusal to provide conclusive or even easily decipherable answers to mysteries that raise their own perplexing set of questions, and it’s here that those new to the film might want to skip ahead to the next paragraph to avoid spoilers regarding later developments. While some of this incomprehension may well stem from impatience with the film’s pacing and almost sleight-of-hand delivery of key information, there are elements that will likely have even those in tune with the Fadel’s approach scratching their heads just a little. A key example is the trio of motorcycle riders that seems to accompany every appearance of the monster. Are they its guardians, a modern-day spectral warning, or are they hunting the creature as it moves from village to village? Don’t hold your breath for an answer to this one because it’s never forthcoming. Occasionally, reality also takes a slightly surreal detour, as in the scene where the Captain lectures Cruz about boredom and fear whilst massaging his scalp in an ever so slightly homoerotic attempt to relieve the policeman’s tension. The film even flirts briefly with the metaphysical, when a wedding ring swallowed by David is seconds later regugitated by the startled Cruz. Then there is the creature itself, a cross-gender monster with a dangling testicular face, a lengthy penis for a tail, and a huge gaping vaginal mouth surrounded by rings of shark-like teeth. It is given no origin story or specified reason for attacking the women the way that it does, which it turns out was a deliberate decision on the part of Fadel, who teasingly suggests that it was born of the story being told within the film. Once again, this can’t help but cast it in a metaphoric light, perhaps as the physical embodiment of male dominance and aggression in a still patriarchal small mountain community, exclusively targeting women that it rapes and beheads, stripping them of their humanity and their identity. With that in mind, it’s telling that the creature is seemingly unsure how to react when eventually brought face-to-face with male potential prey, which it ultimately rapes and mutilates anyway because, well, that’s all it really knows how to do. Of course, I could be way off the mark here, but as the film leaves it for the viewer to provide their own explanations, it’s probably as valid an interpretation as any. That David appears to sense the monster’s presence and could even be the catalyst for its appearance and attacks is also noteworthy, but again, you’ll have to provide the answers and explanations here.

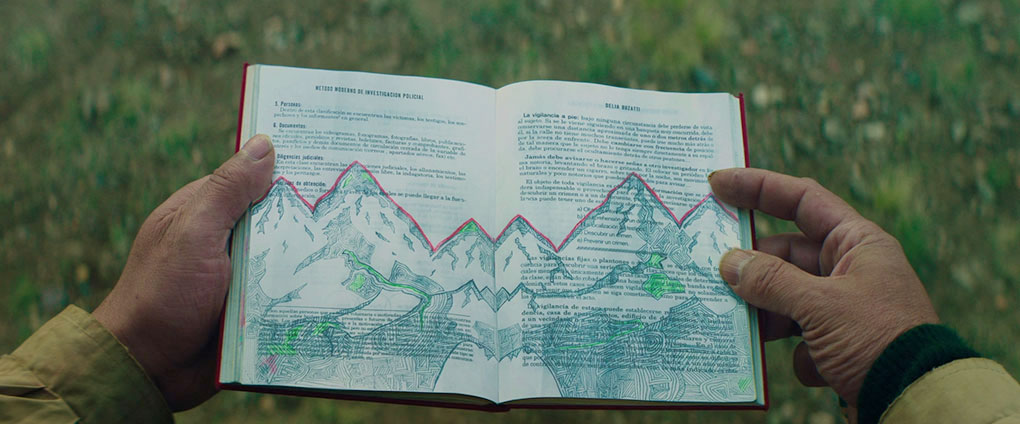

Murder Me, Monster begins with the investigation of a mystery, and over the course of the story develops into a mystery of its own. On the way, it raises questions about loyalty, honesty, locational confinement and even duality, an aspect visually referenced in a symbolically suggestive use of reflections in mirrors, and in one memorable shot, the water of a lake. It paints a troubling picture of the small provincial Argentinean police unit, whose Captain is addicted to Tramadol that he openly shares with his underlings, keeps a bottle of Pinot Noir to swig from in his jeep, and responds to every grizzly discovery by shouting loudly for forensics, as if his voice alone was enough to summon them from home base. Later in the story, the speed with which he makes the decision to cover up a fatal mistake tells a story of its own, as does Cruz’s dismissed offer to lend him a hand. And then there’s that title. It’s later revealed that the triple-M formed from the first letters of the three-word title have a particular significance – drawn from recordings of David’s sessions with the psychiatrist, they collective shape visually echoes the peaks of the mountain landscape in which the answers that Cruz is seeking may possibly lie. It’s this, I suspect, that was responsible for what on the surface is an odd title change from the Argentinean original of Muere, monstruo, muere – which translates as Die, monster, die – to Murder Me, Monster. The reasoning is sound enough, as not only is Die Monster Die! the title of a well-known H.P. Lovecraft-inspired horror/sf hybrid from 1965 starring Boris Karloff, the first letters of this translated title do not form the three ‘M’s that story development eventually requires, hence Murder Me, Monster. Feel free to suggest a more eloquent alternative.

I do get why some have reacted so negatively to Murder Me, Monster, and on a first viewing I was certainly left with a slew of question as the film drew to its enigmatically inconclusive close. But as I noted at the start of this review, I still found myself compelled by the manner in which it is told, by the downbeat and often sinister atmosphere that underscores even the quietest scene, and by the deft storytelling economy and thoughtful precision of Alejandro Fadel’s direction. Despite its sedate pace, the film is richly cinematic in its use of imagery and sound, often quietly observational, but at one point shifting to the subjective to transform a road tunnel into what feels like a reverse descent into the darkest corner of the mind, before snapping the driver and the audience back to reality with a jolt that narratively justifies its existence. As with many of the more challenging films that I tend to cover on this site, this most definitely will not be for everyone, but if you are able to tune in to Fadel’s approach, there’s a good chance you might find yourself as hooked, as intrigued, as enjoyably unsettled, and maybe even as initially bamboozled as I was.

Murder Me, Monster was shot on an Arri Alexa Mini camera fitted with vintage Hawk C series anamorphic lenses from the 1980s to achieve a very particular look that, according to cinematographer Julián Apezteguía, “include an enhanced perspective and several optical aberrations, as well as the distinctive blue flares and bokeh inherent to this kind of lens.” The resulting 1080p transfer, which is framed 2.40:1, is immaculate, boasting a bold contrast range that nails the black levels but retains shadow detail, so important in a film that takes place largely either at night, in the gloom of cloudy days, or in darkened interiors. The film’s deliberately bronze-tinted night-time colour palette is intermittently enlivened by the vivid red or bright yellow of burning flares, while the daylight exteriors have a more naturalistic feel. The image is consistently sharp and the detail is very cleanly defined throughout. Given that the transfer was probably sourced from a digital master, it’s hardly surprising that there’s not a blip of dirt or damage to be seen.

The Spanish DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track is equally impressive, having an excellent tonal and dynamic range, an atmospheric use of ambient sound, and a subtle use of frontal speaker separation. Surprisingly, little use is made of the surrounds for location effects like mountain wind, but they really come to life with Alex Nante’s score, and especially when the superbly mixed sound effects used to suggest the presence of the monster kick in. Bass response is also very good, with some effects and music thundering through the LFE channel.

Optional English subtitles are included for the film and the commentary track, and the appropriate one is activated by default when you play the film or select the commentary on the special features menu.

Director’s Commentary

Director’s commentary, huh? That’s certainly what this is listed as on the special features menu. And yes, director Alejandro Fadel is a key contributor here, but he’s joined by (takes deep breath) cinematographers Julian Apezteguia and Manuel Rebella, costume designer Flora Caligiuri, art director Laura Caligiuri, production designer and field producer Daniel Rutolo, sound designer Santiago Fumagalli, editor Andres Pepe Estrada, and producer Agustina Llambi-Campbell. On top of that, acting as host and asking pertinent questions is Santiago Calori, about whom I unfortunately know nothing more. Having so many people contributing could have led to serious confusion, particularly as it is conducted in Spanish with English subtitles, but herein lies this track’s greatest strength. At the start, each of the contributors introduce themselves by name and their role on the film, and as they do so they are also assigned identifying initials by the subtitles – AF for Alejandro Fadel, MR for Manuel Rebella, and so on. Then every time someone speaks they are identified by their initials, making it clear at every stage who is saying what, no matter how busy the discussion gets. Whoever was responsible for this, whether it be Anti-Worlds or a third party assigned the task, they really should take a bow, as it works a treat. And this is a terrific track that delivers a whole slew of interesting details on the making of the film, which I quickly realised was going to be the main focus – go into this expecting Fadel to reveal the meaning of unexplained elements and you’re likely to be left wanting. To his credit, host Calori does push him to explain what the motorcycle riders represent, but Fadel repeatedly deflects him by assuring him that this is not the time and that he’ll talk about that later. He never does. Areas that are covered include the difficulties of filming in a wild location, the authenticity of actor Víctor López’s extraordinary deep growl of a voice, the use of practical sources like fires and flares for location lighting, how the Sergio Denis song came to be in the film, shooting in and set dressing a real morgue, and much, much more. I was genuinely surprised to learn that at least one of the headless corpses was played by the actress, whose head was digitally removed (I’d have sworn it was a make-up effect), and Fadel does provide some reasoning for cutting two of the deleted scenes detailed below. This is just a sampling. Excellent.

Trailers

Both the Green Band Trailer (1:39) and the Red Band Trailer (2:04) have been included, and in case you are new to those terms, the former usually means a trailer certified for audiences of all ages, while the latter has been certified for adult viewing only. Both are essentially the same cut with more explicit material included in the Red Band Trailer – both are snappily assembled and sell the film as a faster paced horror work than it actually is. But as a sell, top marks.

El Elemento Enigmático (41:01)

This is described in a sentence of introductory text as “a spin-off from Murder Me, Monster that further explores the world hinted at in the original feature, a medium length sensory experience wherein we delve deeper into the mysteries first hinted at…” The key term here is ‘sensory experience’, and if you found the plot of the main feature confusing and frustrating, El Elemento Enigmático may well make your head explode. In it, what I presume are the three motorcycle riders from the feature wander through a snow-covered Argentinean mountain landscape without their bikes, observed by the camera either together, individually, or in pairs, sometimes visually replicated within the frame and accompanied by an overpowering electronic score by J. Crowe. Essentially an avant-garde, figures-in-a-landscape gallery work that abandons narrative in favour of audio-visual experimentation that just occasionally has the ring of a fledgling filmmaker who has just got his hands on the digital effects toolkit for the first time. For me, the simultaneous marriage and clash of sound and imagery proved oddly hypnotic, but it did ultimately leave me searching for meaning that may not even be there, and wondering what the thought process was behind the whole thing. That said, the 41 minute run time really did skip almost invisibly by. The image and sound quality are once again top-notch.

There is a collection of eight Deleted Scenes, several of which are bookended with footage from the sequences in which they were originally intended to appear in order to provide a some context for their original usage. All are edited, sound mixed and scored, and all are of interest. All are accompanied by optional English subtitles, and why they were removed is not detailed here, although a couple do get briefly discussed in the commentary track. If you’re new to the film, you might want to skip past my breakdown of the scenes below, as despite my best efforts to be vague, there are some potential spoilers.

Deleted Scene #1 (1:59) occurs immediately after Cruz finds the head of the first victim and would have provided us with our first look at his notebook (an interesting detail that I failed to shoehorn into my review) and the trio of motorcycle riders, whose appearance prompts the startled Cruz to drop the head, which tumbles to the ground and rolls down the hill.

Deleted Scene #2 (5:22) extends the scene in which Cruz contacts Francisca to tell her that her husband has been seen in the mountains and agrees to go looking for him, against the advice of his colleague Niño, whose assessment of their situation proves the backbone of the sequence. It includes a shot that establishes at an early stage that the police Jeep that later breaks down is unreliable, and a curious shot of Sara sitting naked on the side of a bath. A shot of Cruz looking through a window at the mountains beyond is referred to in the commentary, where director Fadel laments missing the opportunity to get the shot for real, which required him to stage it instead using green screen compositing instead, only to later then decide to cut the shot out.

Deleted Scene #3 (2:25) follows on from the slow zoom of Francisca standing by the lake to observe David cutting wood with the chainsaw he is later accused by the Captain of using to decapitate his wife. When he stops work, Francisca walks up behind him, places an orange in his hand, and reveals that the crops have been saved. The scene is accompanied by a most disconcerting blend of score and sound effects, which ceases suddenly when Francisca aims a mock pistol shot at a shack, a mime that produces in a visible bullet impact.

In Deleted Scene #4 (3:56), Cruz is searching a swamp for Francisca’s decapitated head, and while doing so tells the watching Sara about the birds that feed on the bones of dead animals, while she questions him about Francisca, suggests he gets some rest, and reflects on how nerves are impacting on her body.

Deleted Scene #5 (2:30) extends the first scene at the psychiatric hospital to show David collecting and taking his pills, then sitting down with the other patients in the mess hall, one of whom offers him some transgender porn and asks him if he’d like to see his dick, questions the dazed David barely responds to.

Deleted Scene #6 (4:08) sees Cruz examine the ditch dug by David to escape from the psychiatric hospital (an escape revealed in the film as almost a conversational aside), then observes David himself as he makes his way home, cold and naked, and carries actions that are shown in the film in a truncated form. I can say no more.

Deleted Scene #7 (2:30) is also referenced in the commentary, and has Sara and the female psychiatrist conversing in a car, a scene that initially seems to confirm the attraction between them subtly hinted at in the film as it stands. This is undercut somewhat by Sara’s curt dismissal of the psychiatrist’s suggestion that any of them could have been a victim, noting that the women killed were all under 30, then listing all of the unflattering signs of ageing that would rule the psychiatrist out as a target. The bikers make another appearance here, and in a genuinely creepy moment, one of them walks round to the front of the car, stares in at Sara through darkly tinted googles and a face-obscuring helmet, and begins banging his head against the windscreen.

Deleted Scene #8 (4:28) occurs late in the film after the Captain orders Cruz to leave the building in which they have taken shelter (I dare not reveal more) and shows what happens with the Captain after Cruz has departed.

Unshot Scenes Storyboards (14:12)

This is interesting. Murder Me, Monster writer-director Alejandro Fadel originally planned very different open and closing sequences for the film, but ultimately chose not to shoot them. Here he reads the script for both sequences, which are illustrated by storyboards and underscored by a subtle use of sound effects and music. The opening sequence is by far the longest of the two, and provides a seriously off-the-wall origin story for David. It’s set primarily in a grim prison on the Siberian steppe, into which famed Russian author Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky is thrown to await his execution, only to escape and be transported to the Mendoza desert of the future in by one of the bikers from the film. All clear now? To contextualise the originally planned closing scene would once again be a spoiler, but I will reveal that it involves a trio of monks debating what is the earliest zombies in cinema were, which probably would have been a bit too light-hearted and self-referential a way to end a film such as this. A fascinating inclusion.

Booklet

If you’re hoping to find concrete answers to the film’s more perplexing questions in this attractively produced booklet, you’re also out of luck, but what is here is still of real interest. Following credits for the film, there are comments from writer-director Alejandro Fadel on the location, the theme of a marginal existence, the purpose behind the story’s fantasy element, the use of the triangle motif, and the horror of boredom. A Fadel biography and filmography is followed by a useful short essay by Evrim Ersoy on Argentinean horror cinema, about which I previously knew very little. Rounding things off are some details on the film’s photography , written by co-cinematographer Julián Apezteguía, which I have quoted from in the Sound and Vision section above.

There is one more extra that’s not on the disc, and it has to be one of the neatest special features I’ve ever seen included in Blu-ray release, albeit one that many will not be able to take advantage of. On the last page of the booklet there is a QR code, which will allow you to download the files needed to 3D print your own model of the creature from the film. I mean, how cool is that? The model consists of three parts – one of which is a base with the MMM logo on it – which are then assembled into a single action figure. I do not own a 3D printer, but I have a friend who has access to one at his workplace, and just this morning sent him the files to print out. I am already twitching with anticipation for the result.

Some will and do really dislike this film, but I thought it a gripping and hauntingly executed work, and while a second viewing has failed to clarify the thinking behind some aspects, it brought others into clearer focus and made me appreciate all the more why I became so captivated by the film’s mood, characters and story the first time around. Anti-Worlds have done a typically excellent job here, with superb quality picture and sound and a fine collection of revealing special features. Now I’m just waiting for my 3D model…

|