|

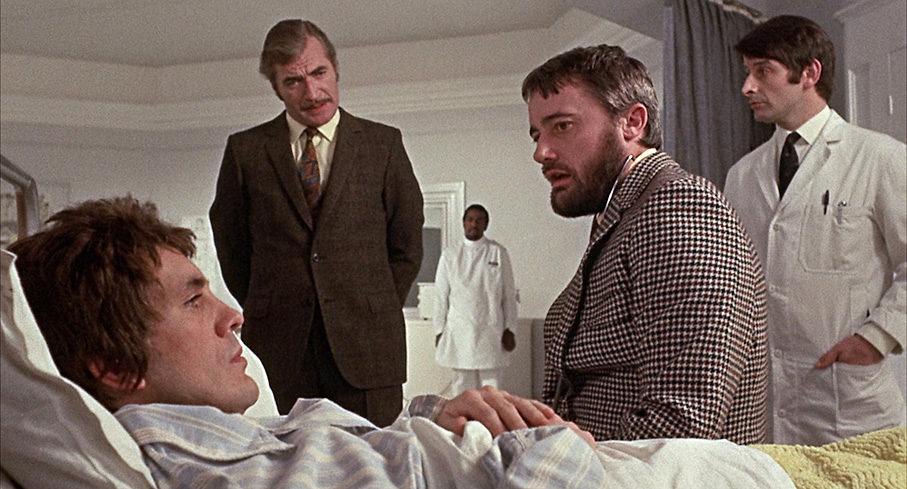

Films in which the principal character struggles to adjust to major societal and technological changes after falling into a long-term coma, being cryogenically frozen or being somehow isolated from the world or even the space-time continuum, are not hard to track down. Some of them are excellent. A couple are damned funny. But this concept is taken a step further in the 1970 The Mind of Mr. Soames, whose title character has been in a coma since birth and is kept at an institute in the British countryside, where his condition is monitored and his bodily health maintained by a medical team specifically assigned to this task. As the film begins, preparations are being made for an operation to be performed by top neurosurgeon Dr. Bergen that it is hoped will neutralise the condition that is causing the coma, waking John Soames from a 30-year sleep.

Long before John is revived you should have a good idea of where the film is going next, and if you're anything like me (and from comments he makes on the commentary track, Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema author Jonathan Rigby certainly is), then you'll be wincing in anticipation. As an adult facing consciousness for the first time in his life, John will clearly have the mind of a new-born baby, and like Mr. Rigby I tend to shudder at the very thought of watching adults of any description pretending to be children and especially infants. Which is why, if you're going to have this in your film regardless, you get an actor with the pedigree of Terence Stamp to play the role. And he really is extraordinary here, authentically capturing the responses and mannerisms of a child in a manner that never comes across as mimicry, to the extent that I quickly forgot that I was watching an actor I've admired for many years and began feeling for John Soames. I even caught myself trying to imagine how it must feel to be in his shoes, to see and experience the world for the first time whilst surrounded by creatures who look just like you but that have an understanding of things that you are ill-equipped to remotely comprehend. Even the first sound that escapes him, more a wail of confused fear than traditional birth cry, feels strangely authentic and becomes the first strand of an increasingly strong empathic bond he forms with the audience.

For some, what unfolds will doubtless play like an interesting concept in search of a story, as the film focuses almost exclusively on how John responds to the environment to which he is initially confined and how his unwitting jailers react to him and his actions. This develops into an unsophisticated but still involving examination of the 'nature verses nurture' approach to child development, with British programme leader Dr. Maitland taking an authoritarian line, whereas Dr. Bergen seems far more attuned to his childhood needs. Thus, when John becomes uncooperative and refuses to eat, Maitland's insistence on compliance get him nowhere, while Bergen gets through to him by initiating a ball game and then having all the staff sit down together and eat, allowing John to feel part of the group rather than the target of curiosity and rigid demands. Bergen then takes this a step further by surreptitiously taking John on his first trip into the woodland outside, something he responds positively to and which delivers a burst of happiness that is then undermined by Maitland's curt demand that he be forcibly taken back inside by the orderlies, even though he was in the process of heading there of his own accord.

The divisions between Bergen and Maitland run further than their oppositional approaches to John's development, as while Bergen only has John's health and welfare in mind, Maitland treats John as an experiment to be studied and probed and appears to be using this to make a name for himself. To this end, he has invited a TV crew led by self-absorbed director Joe Allan to document his work and observe John's development from a concealed location, where he, his assistant and his camera operator (played by a young and uncredited Christopher Timothy) eagerly record his every exchange and confrontation. As is noted in the commentary, this filming of a subject in a controlled location to be broadcast for entertainment anticipates the rise of reality TV. But with John unaware that he is being filmed for public consumption and confined to an environment that he has since his 'birth' believed to be the extent of his world, it also has more than a whiff of The Truman Show about it, and the implications regarding the curtailment of the free will of its subject are every bit as troubling.

While there is a degree of predictability to how the story unfolds, the film still repeatedly undercuts expectations, and as the examples I'm going to give might count as spoilers, I'd proceed with caution or skip to the next paragraph if you're new to the film. That John will find a way to escape his confinement seems inevitable from the moment he gets a euphoric taste of the outside world and is then forcibly dragged by inside by the orderlies, as is the likelihood that his innocence will alternately land him in trouble or prompt a degree of sympathy from others when it does. But it's how this plays out that sometimes surprises. We should all have a good idea what will happen when he walks into a pub, for example, and to a degree things do play out as anticipated, but the beating I expected him to take for his lack of understanding is sidestepped by an inborn instinct to scamper away from potential danger. And when his emotional immaturity comes in conflict with his adult hormonal impulses, it results not in the feared sexual assault but a moment of unexpected and restrained tenderness for both John and a woman whose unfulfilling marriage prompts her only to see goodness in him. Perhaps the most disquieting sequence comes when John boards a train and enters a compartment (not hard to see why these were abandoned in favour of open carriages) occupied only by a young female music student, whom he talks to just as a child would and with the body language of a small boy, but as an ostensibly grown man his innocent words take on an altogether more threatening tone for the unfortunate and increasingly frightened girl. This is underlined when John smilingly tells her that he doesn't like it at ‘The Institute' and puts a friendly hand on hers, prompting her to scream in panic and send him leaping from the train in alarm (a for-real stunt that was clearly done by Stamp himself).

Although it does feel a little underdeveloped at times, The Mind of Mr. Soames is nonetheless an involving and ultimately satisfying work with a keen and sometimes downbeat air of low-key realism (first-time feature director Alan Cooke had previously worked solely in television drama). But perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it was produced by Amicus, a production company primarily known for its horror and particularly its celebrated portmanteau horror films. It's perhaps because of this and the difficulty of compartmentalising the film to a commercially popular genre (I can't help but feel that attempts to categorise it as science fiction are stretching the definition of that genre a little to accommodate this notion) that made it such a tricky sell on its release and has led to it being one of the company's least discussed films. It almost has the air of a departure project, one embarked on by producers and company founders Max J. Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky in an effort to expand out of horror into the realms of prestige drama, a theory given credence by another non-horror Amicus film released that year, A Touch of Love. That Soames failed to find the audience it was looking for is, in retrospect, not all that surprising, and you really need to put the idea that this is an Amicus production out of your mind to get the best out of what the film has to offer. And there's much to admire here, not least in the strength of the performances from a first-rate (if primarily male) cast. Stamp is utterly convincing throughout, but I'll also give an enthusiastic shout for Robert Vaughan, whose impressive restraint and conviction as Dr. Bergen shows a side of the actor – one where his feelings are expressed in the smallest of gestures or changes of expression – that we too rarely got to see. Nigel Davenport is appropriately self-important and blockheaded as Maitland, and Christian Roberts is does a good line in amoral peskiness as go-getting TV reporter Thomas Fleming, despite the curious decision by director Cooke to redub his voice in post-production. Two other noteworthy performances, however, are not quite so prominent. As sympathetic institute doctor Joe Allen, Donal Donnelly is almost a background character, but he always feels like the real deal and an integral part of the medical team, and it's only at the very end that we really get to appreciate how important his role in John's development has been. And as Jenny Bannerman, the lonely wife of the businessman who accidently clips John with his car, Judy Parfitt shows a genuine tenderness and maternal concern for John's welfare that his doctors have failed to realise is completely absent from his conditioned upbringing.

Inevitably, The Mind of Mr. Soames asks questions that it is unable to answer, but it does provoke thought and contemplation on a range of issues, from how the manner in which we raise our children (having none myself, I'm talking generally here) impacts on their future development and how they view the world around them, to how easy it is to misjudge others by misinterpreting their words, their body language or just the tone of their delivery. I'm not about to make a case for the film as a lost classic of British cinema, but it is a fascinating rediscovery that warrants serious attention, and a fine choice for restoration and Blu-ray release.

Another strong restoration and HD transfer from Indicator, framed in the film's original 1.85:1 aspect ratio, that feels consistently vibrant despite the film's intentionally dour atmosphere (the grabs here really don't do it justice) – even the exterior scenes look like they were shot in the glummest weather possible, but colours are always lively, the contrast well-balanced and the image never feels as grim as the world in which the film is set often feels. A fine level of film grain is visible and almost all traces of dust or damage have been cleaned up. There are a few visible halos around heads in the early scenes, which usually suggests the use of digital noise reduction, but it only effects a handful of shots and I'm guessing it's down more to Billy William's lighting.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has the expected limitations for a film of this vintage, with little in the way of bass and a slight treble bias to the dialogue, but is otherwise clear and free of damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Kevin Lyons and Jonathan Rigby

Indicator regular Jonathan Rigby and new recruit Kevin Lyons – who edits the website The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Films and Television, and also provides a fine commentary on Indicator's Absolution disc – both reveal up front that they are fans of the film and have plenty to say about it, ensuring that there's not a dull moment here, with much of what they have to say of considerable interest. Mind you, it's also one of the commentaries that had me groaning at the realisation that just about everything I've said in my review will also receive more authoritative coverage here. This happens to us a lot, but I still prefer to write about a film before hearing or reading what others have to say about it so that I know that the views I'm expressing are my own, even if I later find that they're also someone else's. That said, I did go back to my review and reference the commentary a couple of times to acknowledge that I was not the only one holding the views in question. But I digress. Subjects covered here include the novel on which the film was based and its author Charles Eric Maine, Michael Dress's low-key and sometimes disquieting music score, the main locations, the actors, the 20 minutes that were apparently cut from the film, the underlying themes, the recurrence of the name Maitland in Amicus films, and loads more. A very fine extra.

The Mind of Mr Stamp (18:51)

A new interview with actor Terence Stamp, who at 80 still looks cooler than most 20-year-olds today. He admits at one point that he doesn't really remember too much about much of his work from this period, which is probably why The Mind of Mr. Soames doesn't even get a mention, but what he does recall is too entertaining for legitimate complaint. He talks about his early days at the only drama school that would give him a scholarship, meeting Laurence Olivier on the set of Term of Trial after earlier blowing the chance to join his acting troupe, and abandoning seven years of spiritual retreat in India in a heartbeat when offered the chance to appear in two Superman films with Marlon Brando. Although still often most remembered for his role as Sergeant Troy in the 1967 Far from the Madding Crowd, he claims not to have got on with director John Schlesinger, but still delights in the fact that he was lit in it by Nicolas Roeg.

Memories of Mr Soames (4:57)

A short collection of interview snippets from four of those who worked on the film – cinematographer Billy Williams, researcher John Comfort, actor Christian Roberts and sound mixer John Aldred – who each share some of their memories of the shoot. Comfort recalls having to watch brain operations to get a clear idea how they were performed, while Roberts remembers not getting on with director Alan Cooke and his anger at being told that his voice was to be redubbed because Cooke was not satisfied with his performance. The whole thing is too brief to be of any real substance, and speaking personally I could happily have listened to a lot more from Mr. Williams – when studying camerawork at film school, he was one of the first cinematographers whose name I took note of, primarily for his work on Women in Love, The Wind and the Lion, The Silent Partner, Eagle's Wing and the mesmerising opening Iraq sequence of The Exorcist. When we interviewed Ken Russell, he named him as one of his favourite cinematographers, and if I'm not mistaken, my fellow reviewer Camus worked with him on the 1985 Dreamchild.

Theatrical Trailer (2:40)

What the hell? Okay, we've got wearily used to seeing spoilers in trailers, but this one kicks off with the film's final scene and then proceeds to reveal most of the key plot points that lead up to it. Seriously, don't go near this before watching the film for the first time.

Image Gallery

A substantial 78 slides of promotional stills and artwork, including a couple of behind-the-scenes shots.

Booklet

Keen to see what observations of mine had already been made in more detail by others, I launched into the booklet's lead essay by Laura Mayne, and was not too surprised when it did indeed examine the film and its themes with the sort of authority I've come to expect from contributors to Indicator releases. It also makes for a very fine read. Next is a piece on the stars of the film, constructed from meetings and interviews with Terence Stamp, Robert Vaughan and Nigel Davenport and supplemented by short extracts from Vaughan's autobiography. After this, we have a brief but still welcome piece on cinematographer Billy Williams and a useful essay on the author of the original novel, Charles Eric Maine. Finishing up, there are extracts from contemporary reviews, the only really positive one of which appeared in site favourite magazine Cinefantastique. Press images and full credits for the film are also on board.

A bold and intriguingly low-key work built around an excellent and perceptive central performance and strong support from a very fine cast. I'll admit that on the first viewing it took me a while to get into the story, but I ultimately became completely involved and found myself watching the film again the following day and this time was hooked from the opening scene. Indicator have again delivered a top-notch transfer and laced the disc with worthy special features. It won't be for all tastes, but I have no hesitation warmly recommending it nonetheless.

|