|

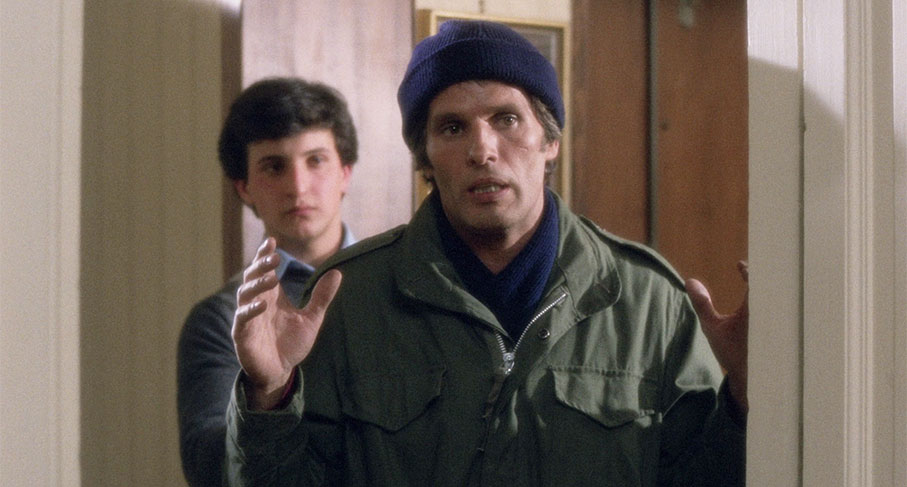

In the Sicilian city of Palermo, two men determinedly make their way down a crowded market street, finally pausing their journey in a small plaza by a drinking fountain. Here, one of them, the scruffy Colicchia (Tano Cimarosa), tells his taller, utilitarian-dressed friend Nino Peralta (Giuliano Gemma) that a well-dressed man (Michele Placido) sitting in a nearby café is a professional killer named Antonio Platamonte, and that he has been asking questions about Nino and is planning to kill him. How’s that for an opening hook? Nino initially brushes off this claim, but is forced to take it more seriously when a local tobacconist confirms that the man was asking where Nino lived and worked, and even points him out when he walks past the shop. And it turns out habitual criminal Colicchia has good reason to be sure of the man’s identity and what he does for a living. But why would anyone hire a professional killer to murder a man like Nino, who runs a small street coffee stall and lives an otherwise ordinary life with his wife Lucia (Eleonora Giorgi), his young son Paolo (Fabrizio Forte) and his rheumatic young daughter Serenella? It’s a question that Nino certainly wants an answer to, and when he sees Platamonte approach his coffee stall whilst Paolo is serving, he walks briskly over to directly confront him, only for Platamonte to assure him that this is a case of mistaken identity and that the questions he was asking the tobacconist were not about Nino but a similarly named friend.

Now, I’ll admit I’m a bit of a sucker for films that reject the traditional approach of first introducing us to the lead characters and giving us time to get to know them and bond with them before hitting them with the narrative disruption that really kicks off the story. Indeed, I have a particular fondness for films that do the polar opposite and hit us with the disruption, or the consequences of it, in the opening minutes, then leave us to become acquainted with the lead characters and discover things about them and their situation as the story unfolds. On paper at least, the initial hook of this approach lies in that Nietzschean need to find order in chaos, a desire to solve a puzzle whose pieces are only made slowly available, and when well executed, this can make for seriously compelling cinema. And so it is with the 1979 Italian crime drama A Man on His Knees [Un uomo in ginocchio], whose lead character’s life is inferred to be in peril before we know a single significant thing about him. As a result, the question of why anyone would want Nino killed is initially wide open to speculation, particularly when he is shown to be a down-to-earth but essentially honest coffee stall owner who loves his family and is working hard to make a better life for them.

That last point is established when a doctor (Fabrizio Jovine) making a house call to attend to Serenella passes casual comment on the family’s new home and the vermin and higher rheumatic disease rates of the slum area in which we can presume they used to live. This offhand remark and its secondary meaning sets the tone for the manner in which even crucial information is delivered, often as almost throwaway lines in the midst of busy conversations, an approach that will require non-Italian speakers to keep a close eye on the subtitles. It's through such conversational exchanges, primarily between Nino and Colicchia, that we learn more about Nino’s past and start to speculate on the reason that he might have become targeted. It’s revealed, for instance, that he used to steal cars for crooked local dealer Carmelo, and that he spent two years in jail for the crime, after which he used the remaining spoils from his criminal days to buy the coffee stall and go straight. Could one of those cars have belonged to someone with dangerous connections, or perhaps have been sold to the wrong person? Carmelo assures him that his operation was watertight and that the vehicles were all shipped to clients in the Middle East, but in such an operation, how sure can he really be?

Nino has good reason to ask such questions, given the power exercised in the district by two warring mafia families and their affiliated gangs, one of which is headed by a man name named Patranca (Giovanni Pazzafini), to whom the now honest trader Nino is forced to pay protection money. And then there’s the month-long kidnapping of the wife of Rao Marina, a lawyer whose underworld position is implied when Carmelo opines that she was taken by the new criminal guard to force the old boss to retire. Initially no more than a conversational news story, its potential relevance is amplified when the police sergeant (Luciano Catenacci) who arrested Nino for a car theft, and who now pays friendly visits to his stall, investigates a report of a bad smell coming from a nearby fish warehouse. Here he discovers the brutally tortured and murdered body of a watchman and a storage room in which it turns out that the kidnapped woman was held. Although the sergeant irritably refuses to confirm it, Nino quickly surmises that the woman was not set free by her captors as reported, but was rescued when the warehouse was stormed by men working for the mafia family for whom her husband works. Could Nino, who used to bring the now mysteriously absent owner Ciccio Capuana coffee orders on a regular basis, be somehow implicated?

The influence of Italian neorealism is keenly felt in A Man on His Knees, with director Damiano Damiani and his cinematographer Ennio Guarnieri stripping the story of any hint of glamour and firmly grounding it in the real world from the opening scene. Aside from top-lights used to separate the characters from the bacjgrounds in darker scenes, much of the lighting is so subtly executed that many scenes do not feel lit at all, and while there are a handful of brief dolly-mounted camera moves, the film is composed primarily of static angles that switch to hand-held coverage when characters go on the move. This realistic approach is matched by performances that even at the most emotionally expressive feel convincingly real. Impressively, neither Damiani not lead actor Giuliano Gemma go out of their way to make the sometimes hot-headed Nino easily likeable, but by grounding him in reality and making his dilemma feel oddly relatable, he becomes a figure of genuine sympathy and empathy nonetheless.

The story itself is told almost exclusively through Nino’s eyes, revealing information to the audience as he discovers it or discusses it with others. At a crucial and unexpectedly early point, however, Damiani briefly breaks with this approach, which affects how we read a key element of the story from that point on. After collecting protection money from the aggravated Nino, Patranca’s two henchmen head back to their garage, where they angrily express their unhappiness at whatever line they were asked to cross at the fish warehouse. Colicchia’s claims about Platamonte and his profession are then confirmed when he enters the premises and executes Patranca and one of his men, his ruthless efficiency tarnished only by the third man he fails to realise is hiding nearby. That fact that we are clearly shown the identity of the executioner – a detail crucially missing from next morning’s newspaper story – transforms how we read the second, more aggressive confrontation between Nino and Platamonte, whose angry insistence that they have the wrong man would have likely also have had me wondering were it not for that earlier scene, and indeed start to sow a small seed a doubt in Nino. Later, when Platamonte approaches Nino’s stall one evening and claims to be a middleman for someone directly connected to the hit, we know that he’s lying, which casts considerable doubt on his subsequent claim that the assassin could be paid off for the right price, an offer that the increasingly desperate Nino takes at face value.

Even at an early stage, it seems clear that things are unlikely to go well for Nino, particularly when Colicchia does some digging and uncovers the true reason for the murders, that eight hits in total have been ordered, and that for still unknown reasons Nino’s name is on the list. It doesn’t help that in his desperate search for answers, Nino risks making matters considerably worse, confronting Platamonte for a third time and beating him up, and paying a foolhardy visit to the home of ageing mafiosi Lamantìa, whom he mistakenly believes has ordered the killings, in the hope of persuading him of his innocence of all wrongdoing. The meeting itself goes badly and ends catastrophically, potentially placing Nino in even more danger.

As things steadily worsen for Nino, his story becomes laced with potent social commentary on how poverty pushes people with few other options into crime, and how this way of living can inadvertently be passed generationally down. Thus, despite his young age, Paolo is learning all the wrong things from a father that he is keen to help protect, instinctively tailing Platamonte to his hotel and reporting back on his current location, and seriously put out when Nino refuses to allow him to accompany him on potentially dangerous missions. He and his friends are also following Colicchia’s disreputable lead by stealing bags from pedestrians, and when the family’s financial situation worsens, the ante his upped for both father and son, when Paolo is arrested for stealing a car radio and Nino reluctantly pulled back into the activity that landed him in jail in the first place.

An accurate translation of the Italian original, the title A Man on His Knees is realised both metaphorically and literally during the course of the film, and while it’s not for me to say how the latter manifests itself, both iterations make for sobering but consistently gripping viewing. I will say that the buildup to the literal interpretation really had me tightening my fists in tension, to two new but instantly memorable characters – one of who is played by once popular leading man Ettore Manni – entering the story, neither of which I can really discuss without getting into spoiler territory. And despite the sense that the story has come to a conclusion of sorts, the film has to more dark twists up its sleeve that lay a path to a grimly toned finale whose open-ended and speculative nature stayed with me for days.

As a study of how quickly the options can narrow for those on the lower rungs of the social ladder when their fragile everyday existence takes an unexpected hit, how easily the desperate can be forced into crime, and how felonious activity can be unintentionally passed down through the generations, A Man on His Knees has the righteous shout of a social activist and kick of an angry mule. It also has no time for the myth-making of The Godfather and its American ilk (films that I do still hold in high regard), presenting the mafia instead from the viewpoint of ordinary Sicilians whose lives are impacted and exploited by these architects of organised crime and caught in the crossfire their of their territorial wars. It’s a pessimistic, deeply downbeat, but superbly handled and performed work from a filmmaker who is now recognised as one of the key directors of mafia-themed films of 1960s and 70s Italian cinema. It also serves as a deeply troubling reminder that even the smallest and most unconscious and innocent act can sometimes, in the wrong circumstances, have devastating consequences.

Sourced from a new 4K restoration from the original negative, the 1080p transfer on this Radiance Blu-ray, framed in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, may at first glance feel just a tad short of sharp, but closer examination confirms that this is not the case. In common with many a film shot largely on location with minimal lighting in the 1970s, A Man on His Knees was very likely filmed on higher speed stock than the old school studio norm, which, together with the earthy, pastel-leaning colour palette, gives the film a gritty, almost 16mm documentary feel. But take a closer look and the level of detail expected from 35mm is absolutely there, and there’s a filmic richness to the image that I’ve yet to see emulated by HD, one that is so, so right for the story being told here. The contrast is well balanced with solid black levels and decent shadow detail, a fine film grain is also visible throughout, and just about every trace of dust, damage and wear has been eliminated. A really nice job.

The original Italian soundtrack has been reproduced here in Linear PCM 2.0 dual mono, and although subject to the expected restrictions in tonal range, the dialogue is always clear, the ambient street sound is effectively mixed, and Franco Mannino’s sparsely used music score is free of distortion. I detected no obvious trace of any former damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default.

Alberto Pezzotta (23:44)

A newly shot and immensely informative interview with Alberto Pezzotta, author of book Regia Damiano Damiani (Director Damiano Damiani), who looks back at the origins of the mafia in Italian cinema and the films in which director Damiano Damiani explored the links between organised crime and high level political figures. Unsurprisingly and appropriately, there is particular emphasis on A Man on His Knees, which Pezzotta describes as one of Damiani’s best films, albeit one whose bleak pessimism he believes contributed to its failure to ignite either critically or commercially on its release. He talks about the lead actors, the long rehearsal process used to create more naturalistic characters, and Damiani’s determination to avoid presenting a picture-postcard view of Palermo. We also learn that while Damiani was beloved by his actors and crew, he had a tempestuous relationship with his screenwriters, some of whom claim that he would completely overhaul their scripts on the night before the scenes in question were due to be shot.

Giuliano Gemma (8:45)

An archival interview with lead actor Giuliano Gemma, who praises director Damiano Damiani and recalls the one point during filming on which they disagreed, talks about serving coffee to unaware passers-by from the stall used in the film, and confirms that the shoot itself went smoothly and that the local authorities were very cooperative when they had to film on the street. He also admits that he loves the film dearly and doesn’t believe it got the reception it deserved at the time of its initial release.

Tano Cimarosa (8:59)

A 2007 interview with actor-turned director Tano Cimarosa (he plays Colicchia in the film), who talks briefly about his entry into theatre and film acting and landing a role in the 1968 Day of the Owl [Il giorno della civetta] for director Damiano Damiani, with whom he worked on a total of seven films, A Man on His Knees included. He states that Damiani was “a director with a capital D,” that he loved Sicily, and that he trusted him as an actor and allowed improvisation, more so than other filmmakers that he has worked with. Although the interview is interesting for its content, whoever was responsible for the sound needs a sharp kick up the arse, as they failed to put a windshield on their microphone when shooting outside on a breezy day, and the wind-on-mic noise is so loud at times it almost drowns Cimarosa out. Thus, even if you are fluent in Italian, you may be glad of the optional English subtitles.

Mino Giarda (20:41)

Also from 2007 and shot by the same people responsible for the above (but this time filmed indoors and with a lavalier mic), this interview with Mino Giarda is a fascinating inclusion, with the fast-talking Giarda cramming a lot into a sometimes fascinating 20 minutes of recollections. He outlines how he came to film late after working as a lawyer until he was 30, and how he was unexpectedly offered the post of assistant director on the 1963 The Reunion [La rimpatriata] when director Damiano Damiani had a bust-up with the man originally hired for the job. He has some alarming stories about being threatened and shot at by the local mafia when making Day of the Owl, and outlines his role in recruiting then postman and bit-part player Tano Cimarosa for the key role of Zecchinetta and the casting of the 14-year-old Ornella Muti for the title role in The Most Beautiful Wife [La moglie più bella] (1970). There’s plenty more here, primarily about the films Giarda made with Damiano Damiani, though it is worth noting that A Man on His Knees was not one of them.

Trailer (3:15)

An Italian trailer that pushes the film as a pacy thriller and that boasts a few spoilers, including that literal realisation of the title that I deliberately avoided revealing above.

Also included with the release disc is a Booklet featuring new writing by Roberto Curti, but this was not available for review.

A prime example of a film in which the lead characters don’t have to be instantly likeable for us to engage with them and emphasise with their fate, Damiano Damiani’s portrait of the downward spiral of an ordinary man for seemingly unfathomable reasons may not be designed to put a smile on your face, but it grips from its opening scene and expertly weaves social commentary into the dense fabric of its storytelling. A rivetingly told and pessimistic work that paints a sobering picture of the devastating impact that mafia power games can have on everyday citizens, it’s impressively showcased on Radiance’s new Blu-ray, and well supported by a solid collection of new and archive special features. Excellent work all round. Highly recommended.

|