| |

"Take The Man from Laramie. Out in the middle of a plain, a man is grabbed and his two arms are held and the gunmen are going to shoot his hand off. Well, it could have been done in many places, but, in the middle of this plain, it was frightening, because there was this beautiful expanse of country with all this evil going on in it. It's the juxtaposition of the very nature of the land, the very mountains, the very rivers, the very dust. All these you use to heighten the drama." |

| |

|

My first real exposure to the cinema of director Anthony Mann came from a sublime combination of chance and youthful enthusiasm. Way back in my first year of film school, when I was still discovering the names of even the more celebrated filmmakers, I landed a holiday job in London a mere fifteen minutes' walking distance from the National Film Theatre, which has since changed its name to the BFI Southbank. Back in these pre-home video days, my only access to movies was through local cinemas (latest mainstream fare) and TV (three channels and a very small screen). Once I landed the job in London and realised where it was located, joining the NFT made perfect sense. It genuinely changed my life. I'm guessing that they screened something like 9-12 films per day in three separate venues and ran everything from old classics to little seen cult favourites to more obscure but acclaimed works from all corners of the globe, as well as conducting interviews with filmmakers and hosting lectures by film scholars. It was here that I saw my first Japanese movie (Kurosawa's Seven Samurai – I've recounted that experience in my review of the Criterion DVD), saw all three Quatermass movies in one afternoon/evening session, and even had a happy chance encounter with Star Wars composer John Williams when I left NFT1 through the wrong door.

I quickly came to an arrangement with my employer to arrive at work an hour later to skip the worst of the rush hour and make up the time at the end of the day, which gave me half-an-hour to walk to the NFT each evening and see whatever was screening. This way I was introduced to films and filmmakers I'd never previously heard of, with the added bonus that I got see the films for the first time on a cinema screen. If a themed season looked interesting, I'd try and catch as many of the films programmed in it as I could. Often I'd be drawn by a director or film that I'd read about in the film books I was slowly ploughing my way through, but occasionally I'd come across an unfamiliar name and just liked the look of the synopses of the films he or she had made. One such filmmaker was Anthony Mann. Back then I'd never heard of him nor seen any of his films, but I was rather fond of westerns and he'd made a whole string of them, each with intriguing titles and seductive programme write-ups. I saw a lot of Mann's films during the course of that season, sometimes two or three in a single day. His early noir thrillers certainly gripped me, and I really had a soft spot for The Glen Miller Story (what can I say? I liked the man's music), but as I'd predicted, it was the westerns that I responded to with the most enthusiasm. What really intrigued me is that they felt like transitional films, ones marking a midway point between the classic genre films of old and the revisionist films to come. This reading was enhanced by the way the director used his favourite leading man. At this point I knew James Stewart primarily from his work in Capra's It's a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and George Cukor's glorious The Philadelphia Story, each of which cast him as a sympathetic and thoroughly likeable beacon of decency. In these westerns, Mann cast Stewart in a different light, as an essentially good but often troubled man who would suffer repeatedly at the hands of others and who could lose his rag and lash out as readily as those who had wronged him. To someone still on a voyage of movie discovery, that made him seem even more interesting than ever.

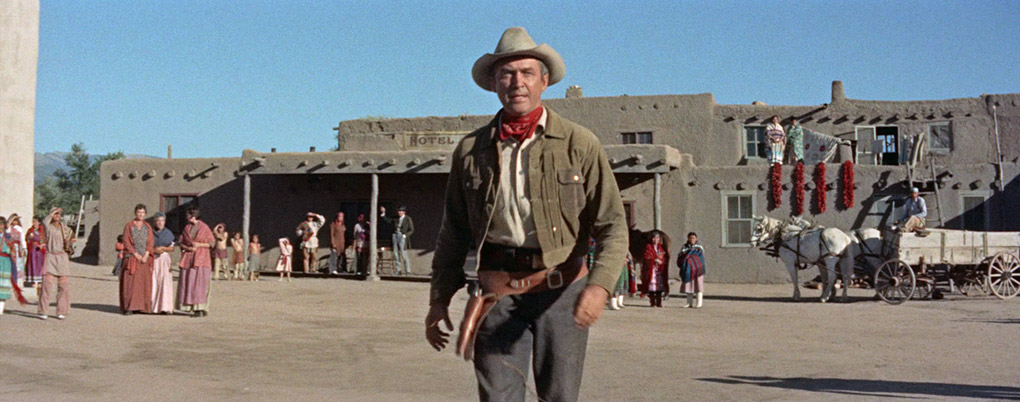

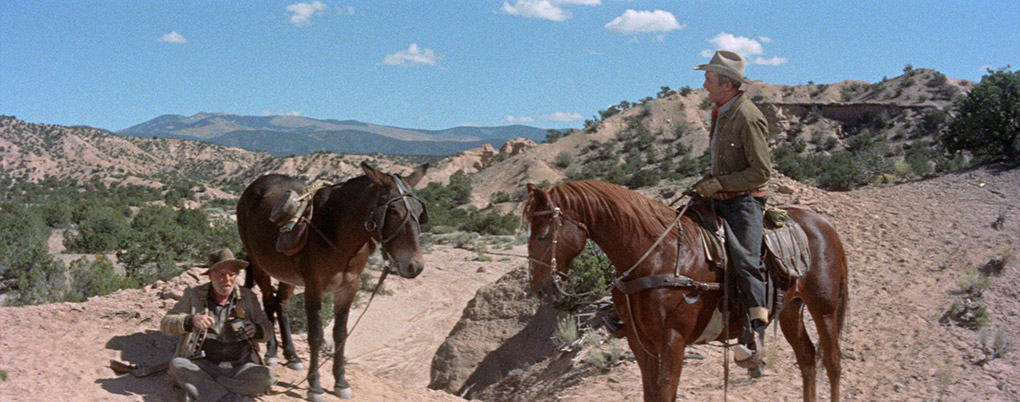

Going by release dates, The Man from Laramie was the final collaboration between Mann and Stewart,** and it's a hell of a film to part company on. Here Stewart plays Will Lockhart, a man with an only hinted-at cavalry background. As the film begins, he and his elderly companion Charley O'Leary stumble across the remnants of an Apache attack that has left wagons burnt and cavalrymen dead, the significance of which only becomes clear over the course of the film. The two men are leading a small wagon train from Laramie to the isolated town of Coronado to deliver supplies, and while there are told of an out-of-town lagoon where they can harvest the ground salt for free. They're in the process of shovelling the salt into their wagons when a party rides up led by Dave Waggoman, who aggressively informs them that they're stealing salt from Waggoman land, then has Will lassoed and dragged through a camp fire, and orders that his wagons be burnt and his mules shot. The only thing that stops him from going even further is the arrival of Vic Hansbro, the Waggoman's more level-headed foreman and the man to whom Dave is still forced by his father to answer.

After paying off his men, Will rides back to town, where he catches sight of Dave and wastes no time furiously laying into him. When Vic intervenes, Will punches him as well and a brawl ensues, one that Dave is prevented from settling with his gun by elderly spinster Kate Canaday, the only landowner whose property has not yet been swallowed up by the Waggoman empire. Kate asks Will if he'll work for her, but he declines when the Waggoman patriarch Alec offers to pay for the property destroyed by his son. When Will is falsely charged with the murder of troublemaking opportunist Chris Boldt, however, Kate makes it a condition of his release into her custody is that he work as her foreman, despite being repeatedly encouraged to leave town by Vic and Alec.

There are a number of familiar western motifs on display here, as a good-hearted stranger comes to town and inadvertently walks into a sea of already brewing trouble, then takes sides with the underdog against the land-grabbing cattle baron who is willing to sweep aside anyone who dares to oppose him. Yet every one of these tropes is undermined by the gradual revelation that nothing here is quite what it seems, or indeed what genre convention has led us to assume. That Will arrives in town with more than the task of delivering goods on his mind is signalled early on and proves crucial to his decision not to head straight back home. The evil cattle baron, meanwhile, turns out not to the malicious monster of genre tradition but a hard-nosed and pragmatic businessman, one who dotes on his spoilt and hot-headed son but who is gradually losing his sight and knows his days are the ruler of his empire are numbered. He is reliant on Vic and treats him almost like a surrogate son, but would still be willing to cast even him aside in a heartbeat to protect his unstable biological offspring. Nonetheless, when he learns what Dave has done to Will's wagons and mules, he immediately agrees to financially recompense him, an offer that Will promptly accepts instead of defiantly throwing it back in his face as expected. And it turns out that Alec's distrust of Will stems not from an anger at this newcomer's actions, but because he's been haunted by a recurring dream in which his son is killed by a man who looks just like him. More than once Will forcefully tries to tell Alec, "I'm not the man in your dreams!"

Vic, on the other hand, is initially painted as the voice of reason and a likely mediator between Alec and Will, and even Alec and his son. Engaged to Alec's attractive niece Barbara – to whom Will delivers his transported goods on arrival and to whom he is also quietly attracted – he's also shown to be a slave to ambition whose recklessness increasingly looks set to engineer his and even Alec's downfall. Even the grizzled Charley (nicely played by Wallace Ford) doesn't play to expectations, coming across as a sincere and likeable companion with none of the comical delivery or cranky demeanour that such characters tend to usually be written in to provide. He's also saddled with an interesting if only partly revealed back story that enables him to ride into Apache territory and make discreet enquiries about who is selling them guns because he is half-Apache himself.

Mann's eye for casting interesting actors into even smaller roles allows each to register in mere seconds of screen time and quietly convince us we've known them for years. Queen amongst these is Aline MacMahon as Kate Canaday, her confident demeanour, self-depreciating humour ("You're just a hard, scheming old woman, aren't you?" Will tells her when she reveals the conditions of his release, to which she immediately responds, "Ugly, too") and cheerfully Winchester-aided intervention into Will's fight with Vic and Dave made me wonder how Will could possibly resist her offer of a foreman's job on her ranch. I'd have done it for nothing more than food and a bed. And yes, that's genre favourite Jack Elam as the dodgy Chris Boldt, whose small but still significant role is still well written enough to allow the character to make his mark.

Mann's direction has its quietly show-stopping moments, a personal favourite being the brilliantly executed dolly shot that travels with Will as he angrily marches towards an unaware Dave, his intentions written all over his face and the camera movement timed to allow him to walk up into mid-shot and then stay with him as he turns and pulls Dave off his horse. Mann also anticipates and simultaneously deglamourises the violence of westerns to come, and the formal fist-fights and showdowns of convention, by focussing instead on the cruelty, messiness and dishonourable nature of physical conflict in all of its guises. Will's punch-up with Vic is a roughhouse brawl in which neither man appears to have the upper hand, one fought in the dirt amidst and even under the legs of horses and cattle. Shoot-outs are similarly shorn of any trace of formalism and traditional 'a man's gotta do' nobility. When Dave finally decides to take a shot at Will, he does so sneakily from behind a rock, and when his hand is injured in the resulting scrappy gunfight he responds by having his men hold Will's hand outstretched and shooting a hole through it at point blank range. In keeping with Mann's approach to violence elsewhere, his camera stays locked on Will's face as it contorts with the pain that this injury has caused. A later conflict between Alec and Will is similarly stripped of its potential violent allure by pitting a man forced to balance a rifle precariously on his bandaged shooting hand against one who can't hit his target because he's almost blind.

The main cast is terrific. Stewart ends a five-film run of westerns for Mann with one of his finest performances, particularly when made to suffer or when his signature amiability gives way to rousing flashes of teeth-clenching anger. Donald Crisp brings just the right mix of authority, ambition and pragmatism to his portrayal of Alec Waggoman, fleshing out and humanising a man who could have easily (and in other films has) been painted as a two-dimensional monster. Arthur Kennedy, meanwhile, presents Vic as a reasonable and essentially decent man, even when he is in conflict with Will, which strips his fall from grace of the satisfaction that casting him as a villain from the start would likely have provoked. Only Alex Nicol's wilder turn as the neurotic Vic plays a little to convention, a portrait of sadistic psychopathy so unhinged at times that it seems miraculous he's not already been beaten or shot before, probably by his own men. Yet it's his twitchy unpredictability makes a key later plot twist disarmingly easy to swallow, as a drastic, spur-of-the-moment decision made by Vic feels triggered in part by his long-standing experience of Dave's behaviour.

A little perversely, perhaps, The Man from Laramie works so well precisely because it refuses to play to genre expectations, despite early indications that it will do just that. Its setup – a man with a mysterious past walks into a conflict that pits a solitary resistant rancher against a powerful cattle baron, and ends up siding with the underdog – is similar to that of Shane, another iconic western classic of the era, but in all other respects the two films are completely different. Here, almost no-one finds what they are looking for – or at least think they're looking for – and there are considerable compromises made by the few that do. Those seeking vengeance end up wreaking it instead by proxy, and as a consequence the satisfaction that they seek and that we as an audience traditionally respond to is intriguingly tainted. Even a romantic union that second-half events seem to be clearing a path for does not play out as tradition would normally demand.

Looking back, it's easy to see why the NFT would screen a season of Anthony Mann films. Mann was an important and greatly talented filmmaker with a string of excellent films to his name, but back then just didn't seem to have the name-drop rep of some of his more celebrated contemporaries. Even today, with our instant electronic access to information and the welcome re-evaluation of his work and influence, I'm guessing that many would have to sit and think hard to name even five of the 42 films he directed, and there are a fair number of genuine classics in there. That he's primarily remembered for a handful of westerns he made with James Stewart gives little indication of the scope of his career behind the camera, but these are still terrific films and The Man from Laramie is one of the best. It's a work that challenged and usurped the codes and conventions of the genre without sacrificing audience engagement or its primary role as cinematic entertainment, and in that respect, it's as important to the shaping of the modern western as the more widely celebrated titles from the likes of Ford and Hawks, and deserves to be held in similar standing.

You know you're in for a treat when even the pre-feature Columbia logo looks great, and this utterly gorgeous 2.55:1 transfer (this was the original CinemaScope aspect ratio) lives up to and even surpasses expectations. Everything is absolutely spot-on here and sings a hymn to Charles Lang's ravishing scope cinematography. The colour is naturalistic without any serious age-related hues, the contrast range generous and kind to low light detail without sacrificing the deep blacks, and the detail throughout is wonderfully crisp – at one point I even caught myself marvelling the clarity of the patterns on crockery in the background. Dust spots and damage have been completely eradicated, and it seems likely that the film was remastered from the original negative, as the quality only momentarily drops during dissolves, which I'm guessing were sourced from a print rather than digitally recreated from the negative scans.

Given the film's vintage, you may be expecting a mono Linear PCM soundtrack, but research suggests that the film was originally screened in 4-track stereo, and that has been remastered here as a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track. Clarity is impressive, the dynamic range good, and the sound effects and music make effectively inclusive use of the front and rear speakers. There is also no trace of damage or background hiss.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Commentary

We've become big fans of Australian film writer Adrian Martin's commentaries for Eureka's Masters of Cinema titles, and once again he delivers an information-packed commentary, albeit one that feels even more like an intensive film theory class than usual. There's next to nothing on the making of the film, but oodles of perceptive analysis of its themes and its characters and of individual scenes (including a wealth of elements I've not even touched on above), which peppered with quotes from other writers and even Mann himself. My favourites on this score are Mann's claim that he is more interested in the exhaustion of his lead characters than their exaltation (that makes so much sense here), and Jean-Luc Godard's suggestion that Mann's westerns are all built around the concept of a man getting himself into a situation and then spending the rest of film looking for a way out.

Video Interview with Critic and Novelist Kim Newman (20:17)

A typically engaging interview with Newman, who seems to misremember James Stewart's "whiskery sidekick" Charlie as a more comical character, but otherwise provides an enjoyable and useful introduction to the film and its many merits. He also touches on the film's theme song and reveals (I didn't know this) that it was a hit twice in the UK, once for Al Martino and once for radio DJ Jimmy Young.

Theatrical Trailer (2:09)

A standard-definition trailer that begins with a fourth-wall breaking intro from James Stewart on the set of the film, then kicks off properly with the above-praised dolly shot and includes a couple of spoilers, so save this for later.

Also included is a 32-page Booklet that features an excellent essay on the film and its making by Philip Kemp, which usefully covers ground not addressed in the commentary. This is followed by extracts from interviews with Mann conducted by Christopher Wicking and Barrie Pattison and originally published in Screen, vol. 10, no. 4/5, July/Oct 1969. Surprisingly (to me, at least), the quote at the top of this review from the very same article has not been included. A little something extra from us, then. Credits for the film, production stills and the usual notes on viewing have also been included.

A personal favourite, lovingly presented in the sort of transfer all such great American westerns deserve. There may not be many extras, but the sheer depth of Adrian Martin's commentary track, coupled with Kim Newman's overview and the booklet material, will leave few people wanting. Highly recommended.

* Anthony Mann interviewed by Chris Wicking in Screen, Vol. 10, No. 4-5.

* Mann's 1955 Strategic Air Command, which also starred Stewart, tends to be listed after the same year's The Man from Laramie, but according to my research, Strategic Air Command was first released in the US on 25 March, while The Man from Laramie didn't hit cinemas until 31 August of the same year.

|