|

If cinema persists for centuries onward it's unlikely to approach the daring commercial gifts of Hollywood in the 1970s. When Elliott Gould was essentially master of the universe he somehow got his M*A*S*H studio 20th Century Fox to make a movie called Little Murders. He initially had Jean-Luc Godard in mind to direct, with Bonnie and Clyde writers David Newman and Robert Benton doing the screenplay, but when that fell through Alan Arkin, who'd never directed a film before, was brought in for his first time behind the camera as well as a one-scene supporting role playing a nervous detective. Adapted by Jules Feiffer from his Obie-winning play about a dispassionate man who photographs literal fecal matter (when he's not getting physically beaten up) and the woman who's intrigued enough to marry him, the film is miraculous in its existence. It's a comedy that's very funny at times and uncomfortably affecting at others.

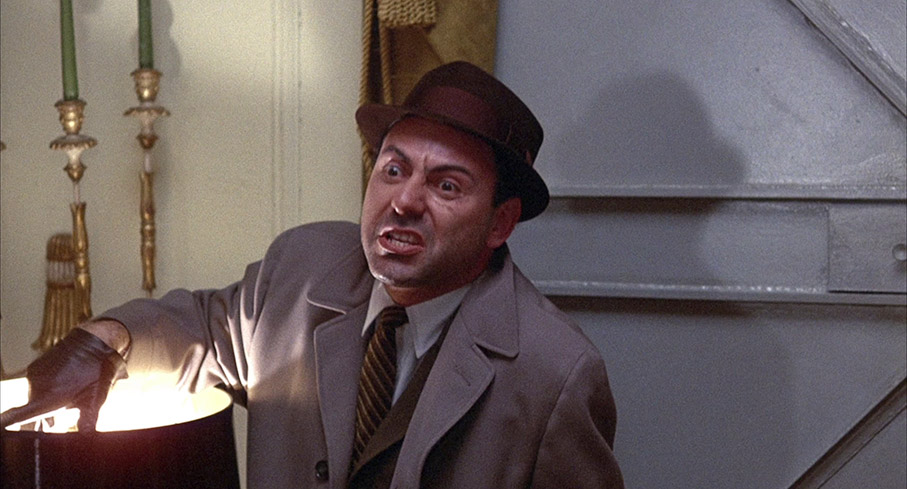

Gould plays Alfred Chamberlain, first seen getting pummeled by youths as Patsy Newquist (Marcia Rodd) runs into the melee to help this stranger she'd heard being attacked from her apartment window. Instead of Alfred showing his gratitude or helping Patsy fend off the attackers he sees an opportunity to move on and wanders away from the fracas. She escapes and confronts Alfred, who actually chastises Patsy for jumping in because the kids, he says, were wearing down. Such is the beginning of a most unusual relationship between disenchanted photographer Alfred and interior designer Patsy amid an incredibly dangerous New York City backdrop. By the time Arkin's detective appears, there have been 345 unsolved murders in the past 6 months, plus some weirdo keeps calling Patsy and breathing into the phone.

After a very cute, albeit brief courtship involving horseback riding and hitting a few golf balls, Patsy takes Alfred to meet her family in yet another strange, off-kilter sequence. Her father Carol (Vincent Gardenia) is quick-tempered while mother Marge (Elizabeth Wilson) seems to willfully ignore much of the craziness in the household, which also includes the creepily unhinged brother Kenny (Jon Korkes). The lights constantly flicker off and on and an earthquake-like disturbance strikes out of nowhere. Conversations prove somewhat enlightening but the real kicker is that Patsy decides to commit herself to Alfred even stronger afterwards, leading to quite the wedding. It's Donald Sutherland presiding over the ceremony and stealing pretty much the entire film in the process. Sutherland has never been better. (Lou Jacobi as a judge also has a super memorable one-scene performance.)

The film turns significantly darker after probably its funniest scenes. Patsy is frustrated at Alfred's seeming inability to show emotion and this progresses into a spellbinding monologue from Gould as he sits at a table in their apartment. What he says concerns an incident from his college days where he became paranoid about being monitored but it speaks to a much larger theme in the film. More than any other scene it's the key to unlocking what can be a fairly difficult film to penetrate. Feiffer's title of Little Murders is at once a reference to the frightening potential of violence to be normalized as well as, maybe, a death by a thousand cuts sort of thing. The metaphorical erosion of the soul by everyday struggles is also something of an effect that comes with such frequency of violence. Feiffer has stated that his initial inspiration writing the play was John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963 and Jack Ruby killing Lee Harvey Oswald two days later. When the movie turns more serious its message is illuminated and, aided by Gould's performance, resonates in a rather unexpected way.

I first saw Little Murders nearly ten years ago, in Brooklyn during an Elliott Gould retrospective with the star on hand for a Q&A after the screening. The audience, a mixture of twentysomethings and those who were probably that same age upon the picture's initial release, ate it up with frequent laughter and intent listening of Gould's every word after it ended. The movie still plays, probably to the same types of people it did in 1971 but maybe there are less of them now than there were then. Its relevancy hasn't been diminished one bit by the passage of time. Vietnam-era politics persist and a late scene where the three male characters act like energized apes following their use of firearms gets its message across as loudly now as it must have when it first opened (and perhaps even better).

Seeing it again is a reminder that Jules Feiffer was a great writer and that Gould was a seventies titan. His work on the three Robert Altman pictures (M*A*S*H, The Long Goodbye, California Split) was more than enough but once this film is factored in and maybe don't forget about his work on Ingmar Bergman's oft-maligned The Touch and something crazy like Busting and only a half dozen or so American actors had as good of a decade as he did. But none were in his specific groove and none had the guts to produce a movie as risky as Little Murders. There's also the easily overlooked contributions of Gordon Willis as cinematographer and Michael Chapman (who'd go on to photograph Taxi Driver and Raging Bull) serving as camera operator. Even as an outlier in Willis' esteemed filmography, it's reassuring to keep in mind that the images were captured by perhaps the single most distinctive director of photography in the history of Hollywood. Little Murders, befittingly I'd say, looks as grimy and frightening as any comedy you'll likely see.

This new Blu-ray release by Powerhouse's Indicator Series might give Little Murders more attention than it's had since it debuted in cinemas in 1971. The film has never received much notice and a previous DVD release via Fox, despite an audio commentary, showed none of the care of a boutique edition like this. This is the first time it's been issued on Blu-ray worldwide. Of note, however, is that unlike the majority of Indicator releases this Blu-ray is locked to region B. The initial run is limited to 3,000 copies.

Video quality is generally consistent and free of damage. The 1.85:1 aspect ratio image keeps a good deal of grain and resembles its era more than some other transfers we've seen from this time period. In short, it looks unrestored to some degree and thick with grain but still pleasing to the eye. Colors are true in what is a generally darkly lit (a Willis trademark) picture. Still, the digital transfer itself seems beyond reproach. The booklet indicates it was sourced from Fox's HD remaster.

The main audio track is an English LPCM affair. It sounds clear and without disturbance. All dialogue and occasional music emerges cleanly minus issue or hindrance. Subtitles are available in English for the hearing impaired.

Bonus material is quite extensive here. Of note, though, is that most supplements are remembrances and little in the way of critical analysis has been offered - perhaps owing to the underseen nature of the film and also its hard to crack tone. They are detailed below:

Elliott Gould and Jules Feiffer Audio Commentary

Taken from the 2004 Fox DVD release, this contains quite a bit of information later repeated among the other supplements as Gould and Feiffer talk a lot about the origins of the film and play.

Samm Deighan Audio Commentary

Writer Deighan goes a different route in her commentary, offering up more of a general discussion placing the film among what was going on at the time of its release and referencing numerous other American pictures from 1971. She seems to be aiming for broader context - also reminding us what a great year this was for outsider-type cinema with Carnal Knowledge, Harold and Maude, Minnie and Moskowitz and A New Leaf, among others, all coming out that year. Consequently, we don't really hear about what's happening on the screen but it still amounts to a smooth, interesting listen.

Introductions by Alan Arkin (0:31) and Jules Feiffer (0:45)

Separate, short intros by the director and writer newly filmed

Beginner's Luck (18:24)

Alan Arkin, wearing three pieces of clothing that are somehow all the exact same color, talks about his first time directing for the screen, including his reluctance and eventual acquiescence of also acting in the film in this interview produced especially for this release.

A Certain Amount of Black (17:34)

The ever-eccentric Elliott Gould talks about Little Murders, including his originating the lead character in the brief first run on stage and eventual role as producer on the film version (which also included a flirtation with Jean-Luc Godard directing). Some tangents are explored but it's also interesting to hear Gould reminisce, and this too was made for Indicator's edition.

Acts of Random Violence (31:30)

Jules Feiffer, cartoonist and writer of both the play and film adaptation of Little Murders, starts by linking the JFK assassination as his inspiration for the mindset that brought him into his work. This lengthy new interview lets Feiffer detail the history of his play, from its writing to the initial productions and onto the film version.

Speaking of Films: 'Little Murders' (30:11)

Susan Rice hosts a panel discussion of Sean Driscoll, Robert Geller, Leonard Maltin, and Jules Feiffer recorded in 1972. This is audio-only and the film plays on the screen as we hear these academics talk to Feiffer about the movie. It's an interesting time capsule and really the only thing we have beyond promotional materials dating from the original release.

Radio Interviews (31:37)

Promotional radio interviews with Gould (7:15), Arkin (7:39) and Sutherland (7:20) done by 20th Century Fox for radio syndication, wherein the local station would ask questions and the vinyl promo record would allow the illusion of live interviews. Here we get to see the scripted questions with the actors' audio playing over it. After the audio we hear an example of exactly how it would've sounded with an interviewer. These are particularly notable as an insight into the marketing of the picture and how things were generally promoted at the time of its release. The answers themselves aren't terribly revelatory but the somewhat deceptive way they were used - with the studio literally scripting the questions for local markets - is interesting.

Theatrical Trailer (3:32)

The original preview seems to play up the satirical elements of the movie.

Larry Karaszewski Trailer Commentary (3:48)

A Trailers from Hell take by screenwriter Karaszewski as he offers a brief appreciation of the film while the trailer plays on screens.

TV Spots (1:51)

A trio of short commercials that would have aired on television upon the original theatrical release.

Radio Spots (2:33)

From 7" vinyl records sent to US radio stations by Fox, there are four total ads ranging from a minute to ten seconds. A picture of the vinyl is shown as we hear the audio.

Image Gallery

49 image screens show stills, posters and press materials including the radio interview scripts.

Booklet (40 pages)

A 2011 essay by musician Jim O'Rourke leads things off. The four-page article allows O'Rourke to share his recollection of first seeing Little Murders as well as offer appreciation for the film's unique qualities, including Gould's haunting soliloquy. The remainder of the booklet opts for mostly shorter pieces, opting for things like Arkin's thoughts on cinematographer Gordon Willis, a correspondence Jean Renoir sent Arkin after seeing the film and a brief exploration of Jean-Luc Godard's flirtation with directing it. There are also reprinted original promotional materials supplied by Fox upon release. One is taken from the sleeve of the LP containing the 30-minute discussion (included in the disc's special features) and another is a discussion guide for "school, college, press, church, and family discussion groups" that seems remarkably optimistic in terms of the projected interest the film would have gained. A short bio of Marcia Rodd (who, unfortunately, isn't heard from at all in these supplements) and a round-up of critical response closes us out.

Little Murders is remarkable and feels quite unique even among the wealth of great films that came out of seventies American cinema. This package from Indicator is more or less an embarrassment of riches, particularly for a film with such a low profile. Its idiosyncratic combination of social commentary with elements of both horror and comedy - a cocktail that helped bring Get Out enormous attention last year - has rarely been attempted much less resonated on the multiple levels we get here. It's maybe not so surprising that Arkin's film of the Jules Feiffer play has existed deep in the periphery since its release but a major edition like this seems certain to find more people willing to embrace its brilliance.

|