|

Following on from the six-film Karloff at Columbia and the three-film Universal Terror, Eureka has released a third Boris Karloff Blu-ray collection, this time sensationally titled Karloff in Maniacal Mayhem. Whether this is appropriate for the included titles I’ll leave for you to judge, but it consists of three films from different decades, the 1936 The Invisible Ray, the 1940 Black Friday and the 1951 The Strange Door. Both The Invisible Ray and Black Friday also co-star fellow horror icon Bela Lugosi, and all three films feature commentary tracks and a small smattering of other extra features, with The Strange Door being the best served on this front.

As ever, I’ve reviewed the films in chronological order, and despite some admittedly petty but good-natured niggles about the science in the first two, I had a great time with all three.

The 1936 Universal horror-science fiction hybrid The Invisible Ray opens with a caption that claims, “Every scientific fact accepted today burned as a fantastic fire in the mind of someone called mad.” Seriously? Try as I might, I’ve not been able to find evidence that people were dismissing the discoveries of scientific minds like Louis Pasteur or Alexander Fleming as the preposterous ravings of unsound minds.

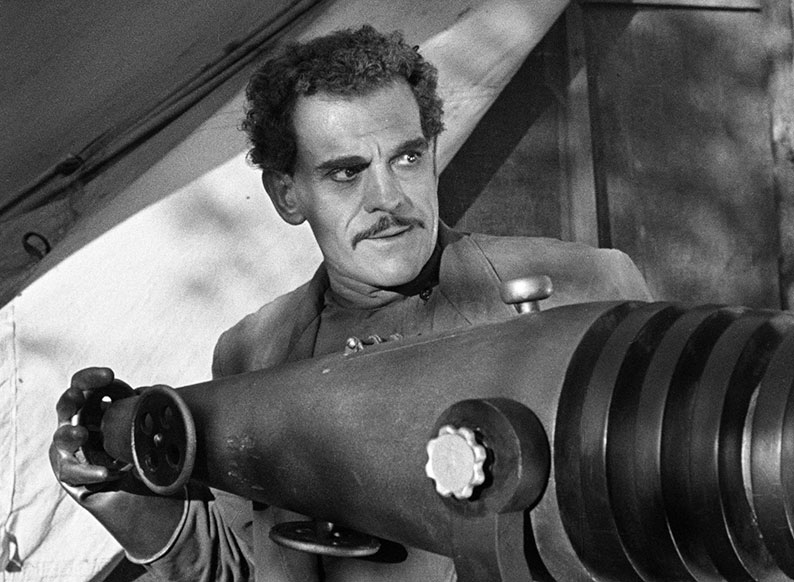

Whether the film’s lead character, Dr. Janos Rukh (Boris Karloff), is mad or simply dedicated to his work and misunderstood by his more conservative peers is initially uncertain. As the film begins, he’s tucked away in a cavernous laboratory in his house in the Carpathian Mountains studying the stars through an observatory-sized telescope, when his young and attractive wife Diana (Frances Drake) informs him that the group he has invited to see his new discovery has arrived. The party in question consists of Lady Arabella Stevens (Beulah Bondi) and her husband Sir Francis Stevens (Walter Kingsford), their adult nephew Ronald Drake (Frank Lawton), and Dr. Felix Benet (Bela Lugosi), with whom Janos clearly has a less than cordial history. To demonstrate the validity of his theory that a meteorite crashed into the Earth eons ago, Janos employs a technological breakthrough that takes the fact that the light from even our nearest galaxy takes millions of years to reach us and runs with it like a terrified cheetah. Using unspecified electronics that spark when activated, Janos is able to ride that light wave all the way to the Andromeda galaxy and back as if doing so whilst carrying a movie camera, on the return journey observing a meteor as it makes violent landfall somewhere in Africa. It’s a scientifically suspect but wonderfully fanciful notion, and the intergalactic journey itself is an impressive bit of effects work for its day.

Far from scoffing at the presentation, Dr. Benet confirms to his initially sceptical companions that what they have witnessed was real and congratulates Janos, even inviting him to join their upcoming expedition to Africa, which would give him the chance to maybe locate this meteor and determine its composition. A genuinely surprised Janos ponders only briefly before accepting but is warned of the dangers of doing so by his ageing mother (Violet Kemble Cooper), who was blinded years ago by an experiment conducted by Janos and his father. Janos goes anyway, and while the others are engaged in their own pursuits, he heads off into the jungle with a party of native helpers. Eventually he locates the meteor, a small piece of which he is able to use to melt a large boulder (another great effect) by harnessing its power to create the invisible ray of the title. He dubs this newly discovered substance Radium X and is excited by potential, but that night when the light levels drop, he discovers that his face and hands have become luminescent (impressive effect number three), and that if he touches another living creature it results in their immediate death.

The Invisible Ray is a film in three distinctive acts of unequal length, each of which is shaped by the changing nature of Janos’s behaviour. In the opening scenes, he is the driven scientist of legend, a man who has dedicated his life to proving a theory that his peers have effectively shunned him for postulating. In the second act, he becomes so obsessed with his quest that his humanity falters, prompting threats to vaporise his native helpers when they want to flee from a site they regard as demonic. His concern for the welfare of others soon returns when one touch from his irradiated hand prompts his dog to drop dead on the spot. Read what you like into the notion that he seems to care more for this animal than he does for the lives the African natives, but he’s outclassed on this score by Dr. Benet when he uses an experimental treatment on the baby of a local woman and refers to it almost contemptuously as “this little creature.”

Janos is greatly concerned about the effect that Radium X has had on his body and – more crucially – the threat it represents to others and makes his way back to the camp in protective clothing to secretly seek the help of his former rival. After studying a sample of Radium X, Dr. Benet develops a serum that supresses its effect on Janos, albeit one that he must take regularly to prevent the condition from reoccurring. This friendliness between the two men is not long-lasting, with the third act anticipating the slasher formula of 1980s horror cinema, with Janos cast as the vengeful killer with a distinctive method of murder and the members of the African expedition party as his hapless victims. This stark shift in attitude on Janos’s part is born of his anger at Dr. Benet for appropriating his discovery – for which Janos was awarded the Nobel Prize, it should be noted – and employing it in his hugely successful private medical practice to cure conditions that would previously have been considered untreatable.

Anyone familiar with the Universal horror cycle and its story arcs should be able to predict that while Janos will indeed kill some of those he rather unfairly holds responsible for his fate, Diana will ultimately be spared and Janos himself is ultimately doomed. For those new to these films, a whopping great pointer is provided in the opening scene when Diana and Ronald first clap eyes on each other – they’re both good-looking and of similar age, and they’re clearly attracted to each other from the off. But Diana is married to Janos, and by 1936 the Hays Office was starting to really put its foot down on things like on-screen infidelity, so you know that Janos will need to be out of the picture before the two can openly admit their love and get together as convention dictates. The film does intrigue on this point by suggesting that all it really takes for Diana and Ronald to be free to marry is to just believe that Janos is dead, even if he’s actually still alive. As far as I’m aware, this is still technically bigamy, but somewhat surprisingly the Hays Office elected to let this one go.

If I seem to be having a few small digs, then know that they are good-natured ones, as The Invisible Ray is a most entertaining late entry into the first Universal horror cycle, one that helped to signal the transition from the monster movies of the 1930s to the cycle of mad scientist tales that was soon to follow. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that in a solidly engaging cast, Lugosi’s low-key performance as Dr. Benet feels more grounded than Karloff’s more larger-than-life turn as the increasingly malevolent Janos. I’ll also give a shout out to Frances Drake, who brings substance to a traditionally lightweight character as young love interest Diana, and Beulah Bondi makes the most of her comparatively small role as Lady Arabella. The various elements are all nicely marshalled by director Lambert Hillyer, a busy jobbing director who also helmed one of my favourite Universal horror franchise sequels, Dracula's Daughter, a film that explores elements of the genre that are more usually associated with modern vampire movies. It may later skimp on the horror and science fiction elements in its last act rush to the finale and tease us with special effects in the first half that are oddly rationed in the second, but this is still a well-structured, niftily paced and highly engaging cross-genre work with a first-rate cast and a rare non-villainous role for Lugosi.

As the ominously titled Black Friday (no cut-price deal jokes here, please) begins, a surgeon named Dr. Ernest Sovac (Boris Karloff) is shown standing in jail cell awaiting execution. As he is subsequently led to the electric chair, he hands his notes to an unnamed newspaper reporter (James Craig), whose publication he claims was the only one that reported his story fairly. As the reporter scans the notes, the film flashes back to reveal the events that led Ernest to this fatal moment.

It all starts when Ernest’s friend George Kingsley (Stanley Ridges), a popular Professor of English History at a Newcastle University (that’s Newcastle in America for us confused Brits) ends the semester with the announcement that he has been offered a post at an establishment of some standing and may not be returning next term. The students all wish him well, then one of them – Ernest’s daughter Jean (Anne Gwynne) – accompanies him to the car in which Ernest and George’s wife Margaret (Virginia Brissac) are waiting. As they head into town, the absent-minded George asks Ernest to stop off at the cleaner’s so that he can collect his laundered hat, and as he crosses the road, he is narrowly missed by two cars in a sequence of rather nifty choreography and timing. Out of the blue, two cars come thundering down the road to the sound of rapid gunshots, which cause one of them to veer off and crash into the building in front of which George is standing. George is critically injured and rushed off to hospital in the same ambulance as the wounded car driver. He is revealed to be notorious gangster Red Cannon, who crashed whilst attempting to flee his former associates, Eric Marnay (Bela Lugosi), William Kane (Paul Fix), Louis Devore (Raymond Bailey) and Frank Miller (Edmund MacDonald).

When they reach the hospital, Ernest discovers that George has suffered irreversible brain damage and that Cannon is paralysed from the waist down and takes the decision to transplant Cannon’s brain into George’s body, something he somehow does in secret, presumably without assistance. To everyone else’s considerable surprise, George then starts to recover, but when Ernest learns that Cannon had $500,000 dollars hidden away (that’s over $10 million in today’s money), he convinces his friend to accompany him to New York, telling him a change of pace will do him good. Instead, he takes him to some of Cannon’s old haunts in the hope it will trigger some lingering memories in Cannon’s brain that might lead him to the money, which he only wants to build a new research centre, of course. At first this seems to be working, but in a moment of emotional crisis, Cannon’s personality resurfaces and takes full control of George’s body, physically transforming the doddery professor into a dangerous gangster with a thirst for revenge against his former comrades.

If I had some questions about the astrophysics of The Invisible Ray, I’ve got plenty more about the medical science of Black Friday. Sovac saves Kingsley’s life by transplanting Red Cannon’s brain into his body, and yet Kingsley still has his own memories and personality. So where the hell is this electrochemical information stored? In his spleen? Of course, if you want to get into a philosophical discussion about the existence and nature of the soul, be my guest, but you’ll be wasting your time debating that stuff with me. But does it matter? Of course not. This is a horror movie made at a time when most of a science was a big bag of potentially sinister mysteries for a sizeable portion of the viewing public and viewed as a genuine threat by some. Thus, the very idea of a brain transplant must have seemed so wildly futuristic a concept that any effect the film might suggest that it would have on the donor must have seemed as abstractly plausible as any other. It also makes for an intriguing take on the Frankenstein story, with the doctor who performs a brain transplant losing control of the unexpectedly destructive donor. There’s also an inescapable Jekyll and Hyde element to George’s transformation to Cannon and back, particularly as both characters are played by British actor Stanley Ridges. This connection to Robert Louis Stevenson’s celebrated and oft-filmed novel is established in the first transformation, a nicely executed dissolve from which we are distracted by the actor’s hand movements and optically overlaid imagery, making it seem like that whole thing happens in a single uninterrupted shot.

It's common knowledge now that Karloff was originally cast in the George Kingsley/Red Cannon role but decided at the last minute that he wanted to play Dr. Ernest Sovac, a part that was originally intended for Bela Lugosi, who was then relegated to the role of gang leader Eric Marnay instead. I say relegated because it’s a comparatively minor part, but once again Lugosi makes a solid job of it, his penchant for delivering lines with a stony face and an amused smile infusing even his more mundane dialogue with a suggestively sadistic undercurrent. Karloff by this point had his ageing boffin persona down to a tee and employs it here to humanise a man who I’d otherwise find it hard to sympathise with, given that he decides early on to sacrifice the life of a man he doesn’t know in a risky attempt to save his friend, a friend he then repeatedly exposes to trauma in pursuit of Red Cannon’s hidden half-million. But stealing the film by some margin here is Stanley Ridges, whose performances as both George and Red Cannon are so distinct – not to mention how different the removal of his glasses and rearrangement of his hair makes him look (eat your heart out, Clark Kent) – that it took me a while to cotton on to the fact that they were played by the same actor.

Black Friday – whose original title was Friday the Thirteenth, a date that appears prominently at moments in the story to suggest it really is cursed – has a few plausibility blips and a somewhat bemusing and unsatisfying conclusion to Marnay’s story, but this is still a smartly paced and entertaining melding of elements from the gangster and horror genres. There’s even a whiff of the noir works to come in a superbly lit and framed wide shot of a reservoir stairway, an ominously lit structure in which the threat is represented by shadows rather than shapes. There’s also a noir feel to the fate of the main characters and an ending that has no time for the traditional comforting shot of two happy young ordeal survivors in each other’s arms. I shall say no more.

At a lively inn somewhere in 15th century France,* Sire Alain de Maletroit (Charles Laughton) walks in, throws a look of barely concealed disgust at a female singer, then sits at a table occupied by his two underlings, Corbeau (William Cottrell) and Renville (Morgan Farley). “Which of these fine fellas is it?” Maletroit asks as he looks around the room with an expression of clear distaste. “Right over there, sire,” says Corbeau, pointing his cane at a man named Denis de Beaulieu (Richard Stapley), who is forcibly snogging one of the serving women, only to then laugh heartily and go in for a second helping when she angrily slaps his face in response. The underlings reveal that Denis seems to be chasing a different woman each night and suggest that he is all that Maletroit could ask for, “a drunken, brawling, cheating villain.” “I’ve seen enough,” Maletroit proclaims after hearing further details of the man’s debauchery. “He’ll do very nicely.” What, one wonders, is going on here?

The three men take their leave, and on their way out give the nod to one of the patrons, who gets to his feet and starts a fight with Denis. It’s a ruse that several other customers seem to be in on, rigging it so that it concludes with Denis grabbing a carefully placed pistol and shooting his opponent. The man is pronounced dead and the place erupts as everyone attempts to apprehend Denis, who flees the inn and jumps into a waiting carriage in which he makes his escape. But wouldn’t you know it, the carriage driver is also in on the plan, and a short while later stops and refuses to budge unless Denis pays him the fare. It’s no surprise that he doesn’t have it, and with the angry posse still chasing, he is forced to abandon the carriage and run. He soon finds himself at the imposing front door of an isolated mansion, a door that then mysteriously opens, allowing him to dive inside. The door closes of its own accord, and once the posse has moved on, Denis attempts to leave, only to discover that the door has no handle. When he ventures further into the house, he is met by the seated Maletroit, who offers him the hospitality of his home as protection from his pursuers. He then reveals that this sanctuary comes at a price, and that Denis has been selected to marry Maletroit’s niece, Blanche (Sally Forrest).

It's an intriguing setup, for which we have to credit Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde author Robert Louis Stevenson, on whose short story The Sire de Maletroit's Door the film is based. Much of what else occurs and most of what is said is down to screenwriter Jerry Sackheim, and it’s difficult to overstate his contribution here. The source material is used as a jumping-off point for a considerably expanded and more convoluted story, and much of the dialogue is superb, and I’m not talking about witty one-liners and ripostes but a quite delicious use of the English language. Pleasingly, this is not reserved for the lead players but is also gifted to the supporting cast and often delivered with the authority, timing and inflection of a Shakespearean play. The story also delivers a couple of neat surprises, even if we can all guess from the moment Denis rejects the idea of being married to “some toothless hag” that Blanche will prove to be anything but, and that she will ultimately awaken in Denis a sense of honour and decency that he has seemingly abandoned.

Karloff plays a supporting role here, much as he did in the following year’s The Black Castle, which was also written by Jerry Sackheim and is widely regarded as the sister film to The Strange Door. Here he plays Maletroit’s abused manservant Voltan, and as with the later film, his role in the story proves to be more significant than first impressions might suggest. It’s a low-key performance in which he tends to be outshone by the superb supporting cast, but even they are effectively pushed into the shadow every time Charles Laughton appears. Laughton is always enjoyable to watch at work, but he’s clearly having an absolute ball here, relishing his lines and littering his delivery with lovely bits of business, seemingly amused by everything he does and says – as Kim Newman astutely notes in his commentary, he plays Maletroit as a man who just enjoys being evil. While his performance does tend to dominate, it’s never to the detriment of the film as a whole, in part because he’s intermittently off-screen for long enough for other cast members to make their mark, then popping up again to delight at everything from the quality of the mutton served at breakfast to what he fully realises is Denis’ deceptively friendly scheming. Fortunately, Richard Stapley has the necessary swagger and self-confidence to hold his own as Denis, and while the role of Blanche may initially seem a decorative one, Sally Forrest injects some welcome life and substance into the character. That the two are ultimately destined to fall for each other despite being forced into a marriage that neither want will likely surprise few, though even I was caught out by the speed with which this occurs, and I’m well used to lightning fast romances in classic era Hollywood movies.

In common with the other two films in this set and a good many of Universal’s early horror works of note, The Strange Door moves at an impressive and fat-free lick, but thanks to Sackheim’s screenplay and that stellar cast, the characters feel more there-dimensional here. The story is well-structured, there are a couple of nicely handled surprises (plus a couple more that you should easily see coming), and first-time director Joseph Pevney pulls off a small miracle in the final scene by getting me seriously wound up (honestly, I was shouting at the TV at one point) by a sequence whose ending is easy to predict. Despite its dismissal in some quarters for its lack of overt horror and the fact that Karloff plays only a supporting role, I enjoyed the hell out of my belated first viewing of The Strange Door, though have to admit that it’s Laughton’s colourful performance that has drawn me back to it repeatedly since.

All three films have been transferred in 1080p in their original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, but whether they have been fully restored or just digitally remastered is something I’ve not been able to confirm. I suspect the latter. Although never razor-sharp in the manner of from-the-negative restorations, all three are in very good shape and have clearly been cleaned up and stabilised. Contrast is decent, with beefy black levels – beefier in some shots than others on The Invisible Ray – and while the picture detail is more crisply rendered in some shots than others, the best material is impressive. Of the three, The Strange Door is in the best shape, perhaps unsurprisingly given that it is the newer film – it certainly is the cleanest and has the most generous contrast range – and for consistency I’d probably give The Invisible Ray a small edge over Black Friday, though both have their quality high points. There are a few remaining dust spots here and there on The Invisible Ray and Black Friday, quite a few at what I’m guessing was a reel change on the first film, and while I spotted a couple of small scratches on both titles, they don’t last long and are not distracting.

All three films boast Linear PCM 2.0 dual mono soundtracks and all betray their age in the narrowness of their dynamic range, though the dialogue is always clearly audible. There’s pleasingly little trace of background hiss or crackle, though there are a few pops on the soundtrack of Black Friday, a small number of which are quite loud.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are present, as expected.

The Invisible Ray

Audio Commentary by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman

The favourite duo of writers and genre experts Stephen Jones and Kim Newman get their teeth into a film they clearly hold in high regard, praising the work of director Lambert Hillier and cannily categorising the film itself as a science fiction work dressed up as horror. They note that this is one of Karloff’s less subtle performances and that Lugosi effectively underplays his character, and praise Francis Drake in what is usually a disposable ingenue role. They pick up on the racism of Lugosi’s description of the native child, suggest that the film is an unofficial adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft’s The Colour Out of Space, discuss the scenes that should be in the film but aren’t, and talk about the lead actors, the characters and the supporting players. There’s plenty more here, and I liked Newman’s suggestion that all you need for a film is a villain with a grudge and a series of elaborate deaths.

Trailer (1:43)

A straightforward trailer that announces its lead player as ‘Karloff the Uncanny’, but has no such exotic suffix for Bela Lugosi. That said, he does come off better here than Karloff, clips of whom seem to have been specifically chosen to accentuate the madness of his character. The trailer is in less than perfect shape, but it’s still a worthwhile inclusion.

There are two Stills Galleries. Production Stills has 26 black and white promotional photos, many of which are of impeccable quality, while Artwork and Ephemera includes 19 screens featuring international posters, coloured-in lobby cards, a single magazine ad, and two VHS video covers.

Black Friday

Audio Commentary by Kevin Lyons & Jonathan Rigby

Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Films and Television website editor Kevin Lyons and English Gothic author Jonathan Rigby are on hand to talk about a film they both like a lot but are not above criticising on a couple of points. They note that it feels more like a Warner gangster film of the period than a Universal horror work, speculate on why Karloff suddenly didn’t want to play the dual central role (Rigby bluntly suggests “he couldn’t be arsed”), opine that his replacement Stanley Bridges walks away with the film, and provide details on a number of the cast members and director Arthur Lubin. They comment on the film’s noir-like aspects, and detail some of the more horrific elements that were in the original script but given a boot by the Hays Office. It’s not hard to see why.

Trailer (1:55)

This fascinating trailer kicks off with a (probably staged) behind-the-scenes shot of Lugosi being hypnotised to play a key scene, a publicity gimmick whose inclusion here includes a massive spoiler for the film. It’s not the only one. A fast-paced sell with cast names written large and fancy transitions between the shots, it’s in a bit of a state, but is still a valuable find.

Again, we have two Stills Galleries. Production Stills has 34 screens of high quality monochrome promotional photos, while Artwork and Ephemera consists of 16 screens containing posters, lobby cards, a nice bit of promotional artwork and a VHS video cover.

The Strange Door

Audio Commentary by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman

Jones and Newman are back to pass comment on a film that they suggest marks the end of the Universal horror cycle, and unsurprising link it to the following year’s The Black Castle. They salute the work of the actors but admit that Charles Laughton overshadows everyone else and come to his defence against reviews that have suggested he was laughing his way through a role that he wasn’t taking seriously. Joseph Pevney is praised for doing a rip-roaring job on his first time in the director’s chair, and there is plenty of discussion on the cast and performances. It’s all typically fine stuff, though my eyes did widen when Jones suggested that the film might have been better if it had been shot in colour, and bulged considerably when he implied it could be colourised. Heresy! Then again, he admits to being a fan of those lobby cards whose garish hand-colouring makes my eyeballs melt. On this point, good sir, we will forever have to differ.

Radio Adaptations

Now this is a bit of a treat. Included here are three radio adaptations of Robert Louis Stevenson’s original short story, each recorded in a different decade and each expanding the tale in different ways. All are ultimately more faithful to Stevenson’s plot than the film is, though frankly that’s one of the reasons I so like the big screen version.

The Sire de Maletroit’s Door (1947) (29:27)

Originally aired on 4 August 1947 as an episode of the CBS series Escape, this audio interpretation stars Elliot Lewis as Denis, Peggy Webber as Blanche, and Ramsay Hill as the Sire de Maletroit. It was adapted by Les Crutchfield and produced and directed by William M Robeson, and does follow the plot of Stevenson’s story, but for the most part goes its own way with the dialogue, but always in the spirit of the original. Only Webber attempts a French accent, and it’s a pleasingly subtle and believable one.

The Sire de Maletroit’s Door (1953) (29:18)

Probably the most prestigious of the three productions here, this adaptation by Britain’s Theatre Royal originally aired on 1 November 1953, is introduced by none other than Laurence Oliver, and stars Robert Donat as Rene and his wife Renée Asherson as Blanche. Despite some research, I’ve been unable to identify who plays the Sire de Maletroit, as he’s only thanked at the end by Olivier as “the rest of the cast.” This is the closest of the three radio adaptations here to Stevenson’s story, and even uses much of its dialogue with only minor changes, sometimes just to bring the language more up to date. Unlike its predecessor, it has a first-person narration, and does flesh out the sequence in which Rene and Blanche fall for each other, making their dual declaration of love seem a bit less of a snap decision. But only a bit.

The Sire de Maletroit’s Door (1975) (43:22)

An episode of the CBS Radio Mystery Theatre that first aired on 6 February 1975, this adaptation is introduced by E.G. Marshall, who also narrates elements of the story that are not told in the first person by Michael Wager, who plays Rene. Blanche here is played by Marian Seldes, and the Sire the Maletroit by William Seldes. This version also follows Stevenson’s story but expands on it by dramatizing some elements that were either communicated through dialogue in the original or left for the audience to imagine, as well as adding a brief opening scene, which like the one in the film takes place at a local inn. Intriguingly, it also includes a narrated postscript, one seemingly drafted to comfort the ultra-moralists in the audience who might be offended by the notion that Blanche would so quickly cast her first love aside. He was just trifling with her, we are assured, and soon after got into a whole heap of trouble that ended in his death, so she shouldn’t and couldn’t have married him anyway.

Once again we have two Stills Galleries, with Production Stills boasting 74 screens of crisp monochrome promotional photos, and Artwork and Ephemera having 23 screens featuring posters, magazine ads (essentially black and white versions of the posters), poster artwork and a single VHS video cover.

Also included is a Limited Edition Collector’s Booklet featuring new writing on all three films by film writers Andrew Graves, Rich Johnson, and Craig Ian Mann, but this was not available for review.

Another terrific Karloff set from Eureka, with three immensely enjoyable films featuring one of cinema’s true horror icons, though it has to be said that he’s ultimately outshone in all three titles by at least one – and sometimes more – of his co-stars. Although the set is not exactly loaded with special features, the three commentaries are all first-rate, and I for one was delighted by the inclusion of those three radio adaptations of The Sire de Maletroit’s Door. Once again, highly recommended.

|