|

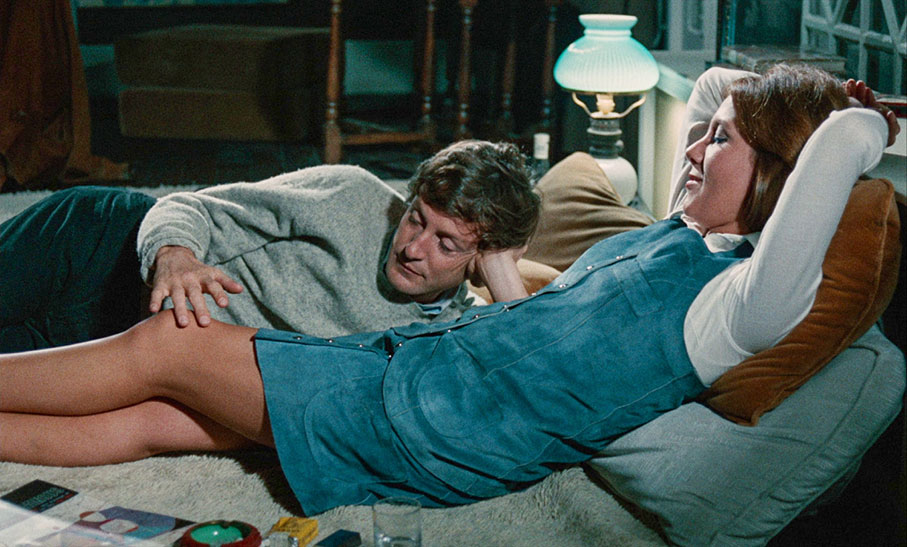

Following a suicide attempt, Claude Ridder (Claude Rich) is approached by a research institute to take part in a scientific experiment in time travel. They have successfully send a mouse back for a minute at a time, and now they need to do the same to a human subject. However, as humans have a sense of time and memory that animals lack, Claude experiences the past in a highly disjointed manner, at times his memories taking him back several years, circling around his unhappy love affair with Catrine (Olga Georges-Picot)...

Je t’aime je t’aime (1968) was Alain Resnais’s fifth feature film, and one that has sometimes been overlooked amongst his works. However it is worthy to be numbered among them. It displays Resnais’s abiding preoccupation with time and memory and its weight on us, here given a science-fictional version. (I first knew of the film from the late Peter Nicholls’s entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction*. SF from now on, as I’m old-school enough not to use the term “sci-fi”, though that battle has no doubt long since been lost.) Like many of the French New Wave, the audience for this and Resnais’s other films in the UK and USA was a small one, those inclined to see subtitled foreign-language films in arthouses, but among them were writers and directors taking note and the devices and techniques used could then percolate into more commercial cinema. The use of jagged memory flashbacks, sometimes less than a second long, which first featured in Resnais’s work in his first feature, Hiroshima mon amour (1959), began to be seen in American and British films in the 1960s. (The Pawnbroker (1964), is a good example.) As for Je t’aime je t’aime, if it has been undersung it has still had its influence, for example on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

Resnais often didn’t write his own films** but liked to collaborate with writers, often favouring those in other media who had not written for film before. For example, with Hiroshima and Last Year at Marienbad (L’année dernière à Marienbad, 1961) he had worked with the novelists Marguerite Duras and Alain Robbe-Grillet respectively, both of whom went on to be film directors in their own right. In 1967, Resnais took part in the portmanteau film Far from Vietnam (Loin du Vietnam), which was supervised by Chris Marker. It was through Marker that Resnais met Jacques Sternberg, a prolific Belgian writer, much of it science fiction and fantasy. Sternberg wrote Resnais’s segment of the film, “Claude Ridder”. Using the same character name for their protagonist (though played by a different actor), they went on to Je t’aime je t’aime, with Sternberg writing at least 250 pages of scenes which Resnais then structured to form the eventual screenplay. Resnais doesn’t take a writing credit, which he could have done, but a measure of the importance his writer had for him can be seen in the opening credits, where they share a title card, with Sternberg is on the left and lower down, Resnais on the right and higher up, the kind of “joint-lead” contractual billing you sometimes find with films with two lead roles (The Towering Inferno and Grease being two well-known examples).

In the opening section, Resnais and Sternberg go into some detail of the mechanics of time travel, but any technical stuff goes out of the window when see the machine itself, the work of art director Jacques Dugied Pace. It’s a very organic-looking device, akin to a brain on the outside and a womb inside, or even perhaps a giant tumour. Resnais films the flashbacks usually in single takes, with the camera only moving to follow characters. As we return to particular scenes, Resnais doesn’t reuse his shots but uses different takes, so Claude’s memory throws up small variations as our memories do. In external reality, Resnais uses a more classical style, cutting back and forth between speakers in dialogue scenes. There are also some fantastical scenes, maybe distortions of Claude’s memories. One memorable image is of a drowning man on the phone.

A major contribution to the film is the editing, credited to Albert Jurgenson and Colette Leloup, enabling the film to remain coherent. Another significant collaborator is Krzysztof Penderecki, who provides a choral-dominated score. His concert work, including five operas and eight symphonies, has been used in films and television (The Exorcist, The Shining and the third series of Twin Peaks, amongst others) but he also wrote some film scores, for example in his native Poland one for Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie,1965). Je t’aime je t’aime was his only collaboration with Resnais, who gives him a showcase of sorts, ending the film with the score over a black screen for two minutes after the final credits.

Je t’aime je t’aime is a complex film which repays close attention, but it’s one which gains on further viewings. It was released in France on 24 April 1968. The following month it was to play in competition in Cannes, but the festival that year was aborted due to the events of May 1968 in France. The film was released in the UK in 1971 under its original French title (not as I Love You I Love You) and this Blu-ray is its first commercial availability in this country since then. It has as of this writing not had a showing on British television.

Je t’aime je t’aime is released by Radiance on a Blu-ray encoded for all regions. It had an A certificate (roughly equivalent of today’s PG) in UK cinemas in 1971, but for this release it now has a 15, the reason for the uprating being Claude’s suicide attempt.

Muriel (Muriel ou le temps d’un retour, 1963) had been Resnais’s first feature film in colour, and for his next film The War is Over (La guerre est finie, 1966) he returned to black and white. However, monochrome was rapidly becoming obsolete in commercial cinema on both sides of the Atlantic, and even arthouse auteurs had to get with the programme and shoot in colour. Je t’aime je t’aime was shot in 35mm Eastman Colour by Jean Boffety and the Blu-ray is in the intended aspect ratio of 1.66:1. I don’t have a copy of any previous version to hand, but Radiance have removed a blue tint from the previous master, so the results do look warmer. Although I’d not seen the film before this Blu-ray, the film’s look is consistent with other Eastman Colour films from the period that I have seen.

The sound is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. Nothing much to report, with dialogue, sound and Penderecki’s score clear and well-balanced. English subtitles are available for the feature and the French-language extras, optional and on by default. These aren’t hard-of-hearing subtitles, and a couple of scenes conducted in English (set in Glasgow) do not have subtitles available. As for the available subtitles, I didn’t spot any errors in them.

Propos de Alain Resnais [sic] (12:45)

This and the next two items were produced for a 2007 DVD release from Editions Montparnasse. In all three François Thomas (author of the book L’atelier d’Alain Resnais) features, here as an offscreen interviewer. Here, Resnais is offscreen as well, presumably by choice, so this interview is audio-only over mostly extracts from the film itself. Resnais says that Je t’aime je t’aime was not his original title, but instead he envisaged something like a beep beep, of a vessel in distress, a SOS. He talks about how he has often worked with writers who have not written screenplays before their collaboration. He bonded with Jacques Sternberg over a love of the cartoons in the New Yorker. He discusses how the film nearly folded due to lack of funding, and if François Truffaut had not pressed Mag Bodard to complete the budget, it would not have been made. Resnais said that if Claude Rich had not played the lead, he would not have made the film either. He argues that the film actually contains no flashbacks, as the memories, scattered as they are, are present for the film’s protagonist.

Interview with Claude Rich (15:45)

Rich, interviewed by Thomas (again offscreen), describes Je t’aime je t’aime as his best cinematic memory, though at first he would not have appeared onscreen, though of course he does a lot in the finished work. He closely identified with his character as not only did they share a given name, he wore his own clothes on screen. He also talks about the film’s appearance at Cannes in 1968 and again at a special screening there in 2001. By then, obviously, he had aged and so he had the experience of watching someone on screen who was “him but not him”.

La rencontre Resnais-Sternberg (20:31)

François Thomas again, this time onscreen. Sternberg appears in extracts from an archival interview from 2001, as he had passed away in 2006. Thomas points out that Sternberg’s main virtue was concision. Although Sternberg had written novels (Un jour ouvrable (A Working Day, 1961) was a favourite of Chris Marker), after a while he stopped writing them and concentrated on short fiction, producing some 1500 to 2000 stories, many of them assembled in fourteen collections. Je t’aime je t’aime used material from some of them: Claude Ridder is a character name in several of them (and, as mentioned, in his segment of Far from Vietnam), as is Catrine, whom he based on his own wife. Sternberg would in turn reuse material from the film in his later work. Thomas goes into some depth about the film in hand, describing its timespan (memories going as far back as 1951) and its shooting style. Although the film does seem very fragmented, Thomas points out that while it does contain around 330 shots that’s a third of the number in Muriel (admittedly twenty minutes longer).

David Jenkins on Je t’aime je t’aime (12:46)

This appreciation by Little White Lies editor Jenkins was recorded for this release. To begin at the end, he regards Je t’aime je t’aime as perhaps Resnais’s masterpiece (no small claim) and one of the great unheralded films of its time. He saw the film in about 2011 and makes the comparison in its style and techniques with Terrence Malick’s later work, particularly The Tree of Life (2011), serving as possibly its template. To return to the beginning, Jenkins talks about the origins of the film, from Resnais’s meeting with Sternberg and a description of their episode of Far from Vietnam, in which Claude Ridder was played by Bernard Fresson. This Claude Ridder delivers a monologue about Vietnam while a young woman (Marie-France Mignal) listens or is perhaps being talked at. Though this was a more political piece and Je t’aime je t’aime is science-fictional, Jenkins sees a connection beyond simply the character name as the later feature does centre on the relationship between a man and a softly-spoken woman. He talks about the use of time in the film, particularly the jazz-inspired editing and the writing process. Jenkins sees this as not so much a time-travel film as an investigation into memory and how it and the mind works. It is possible, he says, to feel “alienated” by the seemingly random events we see on screen. I do have to take issue with some of this, as Jenkins seems to be wanting to move the film away from being SF towards other things, with which SF is not incompatible. (SF can quite easily have realistic settings along with its genre elements, for example, for all Jenkins’s attempts to distance the “fantastique” from it. If the film has elements of murder mystery and especially romance, that doesn’t mean it can’t be SF as well.) Jenkins talks also about Penderecki’s contribution and some of the themes it shares with earlier works such as the legacy of war (Nuit et brouillard (Night and Fog, 1956), Muriel). Although I have some reservations, this is a very useful piece. It’s best watched after the film, or at least your first viewing of it.

In the Ears of Alain Resnais (Dans les oreilles d’Alain Resnais) (54:31)

Much has been said about the use of editing in Resnais’s films, and the input of his cinematographers has been discussed, but in this 2020 documentary made for French television, directed by Géraldine Boudot, here we have his use of sound, especially music. Resnais had no musical training, but it was an art form that had a lot of impact on him. Some of his films even feature musical numbers, for example La vie est un roman (literally Life is a Novel but released in English-speaking countries as Life is a Bed of Roses, 1983) and On connaît la chanson (Same Old Song, 1997). The latter features characters periodically lipsynching to songs Dennis Potter style, with Potter thanked in the credits. As Resnais frequently worked with different writers from one film to the next, so it was with composers. He had a principle not to work with the same one more than twice, although he did break that rule towards the end of his career. The composers he worked with covered a wide range. Stephen Sondheim was a particular favourite of his, though they worked together just once, on Stavisky (1974). Krzysztof Penderecki was another one-timer, on the film at hand. The composer Philippe-Gérard was a two-timer: La vie est un roman and Mélo (1986). Resnais was a fan of The X Files and indeed was the President of the French X Files fan club, and as a result he hired the show’s composer Mark Snow to score his final four feature films. Snow is interviewed, as other interviewees include the actor Lambert Wilson (who says that Resnais often cast his films by means of voices rather than looks or anything else), actress/writer/director Agnès Jaoui (who worked with Resnais twice, acting in and co-writing On connaît la chanson and co-writing Smoking/No Smoking), Bruno Fontaine (score composer for On connaît la chanson), Resnais’s regular editor Hervé de Luze and critics Michel Ciment and François Thomas. Clips from several of Resnais’s films are included, though the device of superimposing the interviewees over some of them while sitting in their chairs could have been done without. An in-depth item like this is a welcome addition to this disc. I can’t imagine something like this being made for British television, then or now.

Booklet

This limited edition contains a booklet with new writing by Catherine Wheatley, but this was not available for review.

Je t’aime je t’aime is one of Alain Resnais’s more undersung films, but it’s certainly a major one. This Radiance Blu-ray restores it to commercial availability in the UK, with some very well-chosen and insightful extras.

**He is credited with adapting four stage plays for the screen, starring with Mélo (1986). However, on Wild Grass (Les herbes folles, 2009), You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet (Vous n’avez encore rien vu, 2012) and his final film Life of Riley (Aimer, boire et chanter, 2014) he used the pseudonym Alex Reval.

|