|

Hollywood films headlined by two major stars must seem like both a gift and a curse to those tasked with marketing them. Theoretically, you have twice the star-pulling power of other movies, but you also have agents and egos to deal with, and you run the risk of upsetting both if you favour one star over the other in your promotional material. This, of course, is how we end up with posters featuring equally sized images of both lead actors with their names above them, but reversed so that each of them gets to be first in one way or another if you’re reading left to right, as we tend to in the west. Oh, the fun poster designers must have if there are three of them…

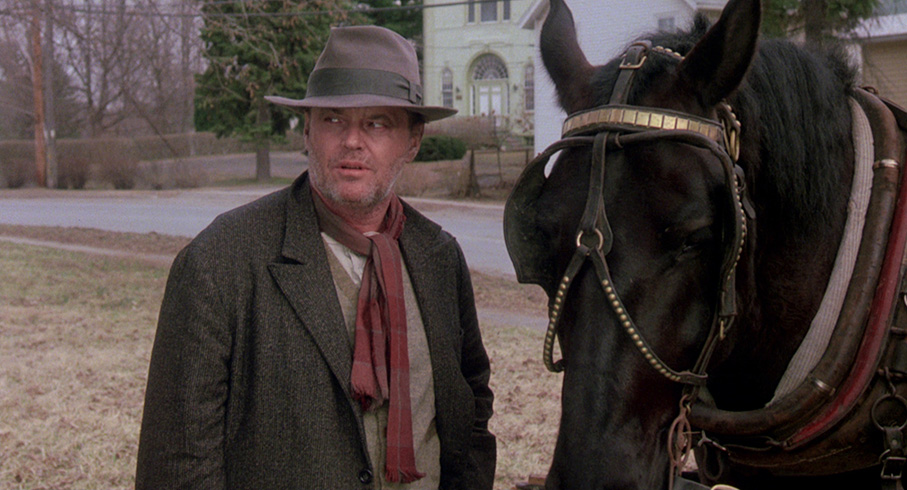

One such film is the oft-forgotten 1987 Ironweed, which stars the heavyweight duo of Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep (or, for balance, Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson) and whose poster follows this name-swap convention, while the status of both actors is signified by the fact that only their surnames are used. What intrigues most about this poster, however, is that both actors are framed in close-up but locked in a kiss that sees their faces obscured by Nicholson’s hat and the shadow it casts. So well-known were these two at this point in their respective careers that we didn’t need to told their first names or see their faces for the poster to act as a hook. Or at least that’s the theory. Whilst the pairing-up of action stars may pay commercial dividends, it doesn’t always work the same way with dramas and particularly, it would seem, with period dramas. Ironweed had a production budget of $27 million but made about $7.3 million at the box office, and that’s despite Oscar nominations for both of its lead actors. Quite why audiences gave this one a miss is anybody’s guess – eight years later when Streep teamed up with Clint Eastwood for The Bridges of Madison County, another drama based on a highly respected novel, the film pulled in a by-comparison whopping $182 million against a $22 million production budget. Of course there’s a considerable difference of tone between these two movies. Both have love stories at their core, and while there is sadness in Bridges, it’s not a downbeat movie. Ironweed, on the other hand...

To describe the plot would probably do the film a disservice, as while a narrative of sorts unfolds and character arcs play out, Ironweed is primarily a character study that also paints a picture of the time and place in which the story takes place. Set in the Albany district of New York on the cusp of winter in 1938, all of its principal characters are homeless, victims of fate at a time when so many of their countrymen were in the same boat. Millions had been driven into destitution by the stock market crash of 1929, which gave birth to the Great Depression from which America at this point had still not recovered. One of these unfortunates is middle-aged Francis Phelan (Jack Nicholson), who as the film opens is seen slowly unwrapping himself from the coverings that have kept him from freezing on the windy, rubbish-strewn side street on which he has been forced to sleep and who then makes his way to a local Mission, outside which his fellow bums gather around the welcome warmth of a brazier. One of them, Rudy (Tom Waits), greets him warmly wearing a smart but ill-fitting suit and a fine pair of shoes, which he reveals that he picked up at a hospital where he has just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. “First thing I ever got,” proclaims the ever-upbeat Rudy triumphantly before revealing that he has been given just six months to live and that has decided instead to drink himself to death.

Francis has got word that there is a day’s work digging graves at a local cemetery and invites Rudy to join him, and it’s here that the film pulls what for me was its first structural surprise. The standard approach would be to drop small hints about Francis’s backstory before later revealing – probably in a pivotal scene – how and why he ended up on in dire straits, but here that revelation, or at least a key part of it, comes just ten minutes into a film that at this point still has well over two hours to run. It happens when Francis kneels before the gravestone of his infant son Gerald, who died just 13 days after he was born when he was accidentally dropped by Francis who may or may not have been a little worse for drink at the time. We learn all this when he breaks down and recalls this most painful incident in an apologetic conversation with Gerald’s memory, and a short while later he’s being haunted by the ghost of a tram driver that he inadvertently killed during a confrontation with authorities during a labour strike. As you might be starting to gather, Ironweed is not an ideal date movie, but it’s worth noting that we’re just getting started here.

After returning to the Mission for a meal and turning a cynical ear to the hymns and words of a tolerant pastor who gives him a tip for where he might find some more work, Francis is joined by Helen Archer (Meryl Streep), a twitchy and contrary down-and-out whom Francis has clearly known for some time and is, in his way, rather fond of. Helen is also carrying some serious emotional baggage, and over the course of the film it becomes clear that both she and Francis once notable in their respective fields, she as a singer and Francis as a baseball player. Both also do have story arcs of sorts, neither of which it would be fair to elaborate on here, despite the fact that their conclusions are telegraphed well in advance of their occurrence.

This, I would suggest, is where the fault lines of audience division will likely set in, as if you don’t engage with the characters then a sizeable portion of the film’s first hour is likely to prove a slog, and the key to the success or otherwise of that engagement lies in the lead performances. It is, without question, a powerhouse teaming, but not without its risks, given Streep’s occasionally distancing commitment to technical perfection and Nicholson’s post-Shining penchant for sometimes playing to the gallery, but here both are on phenomenal form. Well, kind of. As ever, I’m speaking from a personal perspective here, and one that did undergo a gear shift as the film progressed. Allow me to clarify. When the film was released, praise aplenty was heaped on Streep’s performance and it’s not hard to see why. Yet on my first viewing of the film I was perhaps a little too aware that I was watching an actor playing a role. Nicholson, by contrast, gets so completely under the skin of his character that I came close to forgetting that I was watching an actor whose face I know only too well. For the first half at least, Streep creates a fascinating character in Helen, whereas from the moment he first wakes up on the roadside and shuffles into town, Nicholson somehow feels as if he has lived as Francis for a number of years. In a career liberally peppered with great performances, this, for me, is one of his very best. Only later in the story, when it dawned on me that as a former singer of note, Helen has lived her adult life as a performance and is still struggling to come to terms with the fact that she is no longer in the limelight. This realisation on my part prompted me to re-evaluate how I felt about the more seemingly ‘performed’ aspects of Streep’s portrayal and see them not as tics of the actor but the character she is portraying. Later (and hop to the next paragraph if you want to avoid spoilers), as things take a further downward turn for Helen, Streep really comes into her own, notably in a scene set in a café when she has the money for tea and toast, then hesitantly nibbles at the latter in a manner that signals clearly to us, without a hint overstatement, that she is no longer able to ingest even the most basic of foods and that she is now on a probably irreversible and very private slide towards impending death. All this from how she toys with a piece of toast.

The harsh nature of life for those who have fallen victim to the collapse of American capitalism is certainly brought home, though in the characters of Francis and Helen is just occasionally at risk of being romanticised. Individual sequences still hit home, notably when Francis, Helen and Rudy discover homeless alcoholic Sandra freezing on the streets and carry her to the Mission, where she is refused entry for only hinted-at reasons and is only given a bowl of soup and a blanket by these supposedly charitable people because the indignant Francis demands it. The film also explores the very real issue that in times of economic hardship, even seemingly secure and successful can be plunged into poverty by the sort of unexpected turns of fate that any of us could fall victim to. Though nowhere near as hard-hitting as the portrait of life on the lowest rungs of society found in director Héctor Babenco’s searing 1981 breakthrough feature Pixote, it still serves as a potent warning at a time when our own society’s broken excuse for a safety net is on the brink of being torn into shreds, and when a sizeable proportion of the population is calculated to be a mere two pay cheques away from destitution and potential homelessness.

In spite of the presence of two major stars of the day, Ironweed doesn’t have the feel of studio picture (it was a co-production between Taft Entertainment and HBO) and it benefits from that, able as it is to retain the appropriately downbeat tone of the Pulitzer Prize-winning source novel by William Kennedy, who also wrote the screenplay for this film. It never tries for the cinematic gut-punches delivered by John Ford in his 1940 adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (another Pulitzer Prize-winning novel set in the Great Depression), instead adopting a more sombre and melancholic approach that feels appropriate for the material but that some will definitely struggle to engage with. And it takes its time, an increasingly rare quality that allows us to get know the lead characters a little before they embark on their clearly telegraphed but still moving narrative journeys. Downbeat, yes, but still involving and authentically humanist and bolstered by strong performances across the board (Waits’ hoarsely spoken twitchiness is just right for the doomed but upbeat Rudy), the film’s warning of the consequential suffering created by the greed and the failings of unchecked capitalism frankly couldn’t be more timely.

In common with many of its cinematic brethren, Ironweed elects to visually suggest its period setting and the glumness of the protagonists’ hand-to-mouth existence by stripping back the colour and favouring earthy tones. Pleasingly, however, this has not been overdone, and has been achieved in part through the set design and costumes, allowing for more natural flesh tones in some daylight scenes and the occasional bright colour (the red neon of lights of shop signs), though when the Francis, Helen and Rudy hit a bar run by Oscar Reo (Fred Gwynn), the colouring goes full sepia on us. About the 1080p 1.85:1 transfer I have no complaints, as even with the colour tinting becomes more pronounced, the contrast is always nicely balanced and the black levels never slip into washed-out greys or sepia browns. Detail is crisply rendered and the image is free of damage and dust.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack boasts a solid dynamic range, reproducing dialogue and music clearly with no crispness to the trebles, some decent bass heft to the rumble of trains on tracks, and some clearly detectable frontal separation.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Trailer (2:07)

A less-than-pristine, 4:3 framed trailer whose sound is slightly out of sync with its picture (evident when Meryl Streep is seen singing the song that dominates the trailer’s latter stages) and that promotes the film primarily on the strength of critical acclaim for its two lead performances.

Also included with the release version is a Collector’s Booklet featuring new essays on the film by Lee Gambin and Simon Ward, but this was not available for review.

I have to admit that I approached Ironweed a little apprehensively, convinced as I was that its star power would prove a distraction for a story that theoretically would be better served by lesser-known character actors, yet here I’m happy to concede that in this case the director really did know best. It’s a downbeat and ultimately tragic film, one driven more by its characters than its slender narrative, but is so well acted and so richly textured that it rewards and even demands a second or third viewing. Having been released on the Eureka Classics label, there is precious little in the way of extra features, but the transfer is first-rate and even this shortly after its release can be picked up for less than £13, and it thus comes heartily recommended.

|