|

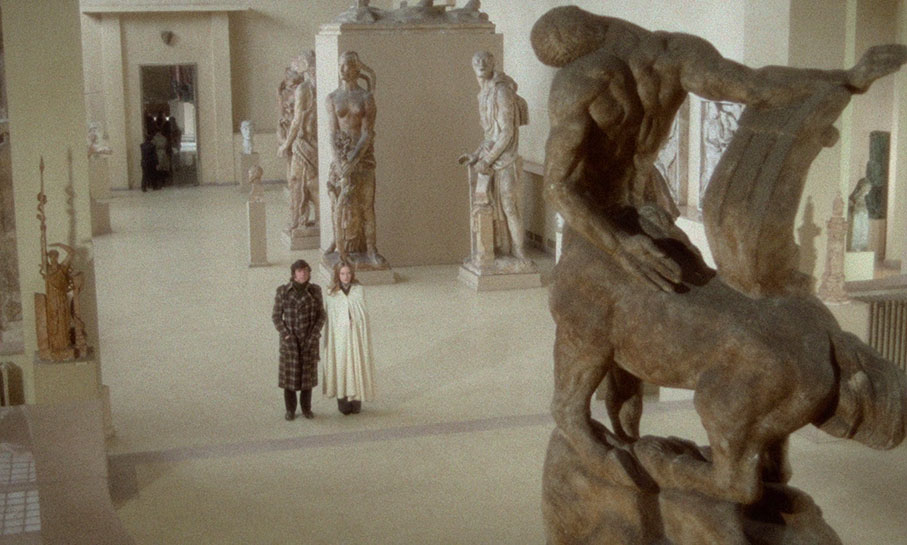

Depending on which version you elect to watch first (more on that below), the 1973 Impossible Object kicks off with a scene that is open to multiple readings. It begins a little disconcertingly on a close-up of a sculpted hand that focus-shifts to a young woman, who is observing the artwork and those around it with the expression of someone who is as disturbed by the work as much as she is curious about it. It’s a perception enhanced by Michel Legrand’s score, which alternates between the urgent and troubled strings of a psychological thriller and something altogether gentler and more contemplative, which is then undercut by low, off-kilter cello notes to subtly unnerving effect. As the woman continues her journey through what we soon see is a museum, she is noticed by a man who is making notes in front of one of the exhibits. He continues to observe her as she walks over to a sculpture a short distance away, and after a pause he walks quietly over to stand beside her. The film then cuts undramatically to an exterior wide shot of the entrance to the museum, through which the man and woman emerge, now hand in hand with wide smiles on their faces. The camera then pans slowly right to reveal that we’re on the bank of the River Seine in Paris just a short distance from the Pont-Neuf bridge, identifying the museum as the world-famous Louvre. As the titles unfolded, the two walk down the bank of the river and enter a busy brasserie, sit down for lunch and exchange looks that are equally open to interpretation. “Would you…?” begins the man. It’s at this point that the film cuts almost jarringly to the next scene.

So what exactly happened here? Here are three possible options that struck me the first time I watched it:

-

The man is seeing this woman for the first time and is struck by her beauty, and when she pauses to look at a particular sculpture, he walks quietly over to stand beside her with the aim of starting a casual conversation about it, and the two quickly find that they are attracted to each other;

-

The man and the woman used to date and have not seen each other for some time, and the man is surprised to find himself in the same location as his former lover and apprehensively approaches her – when she sees him and realises who he is, their former attraction to each other is instantly revived;

- The two are secret lovers who have planned a clandestine meeting at the museum that the man was convinced the woman would not keep – after seeing her and pausing to contemplate the risk they are taking, he approaches her and the two head off for their planned date.

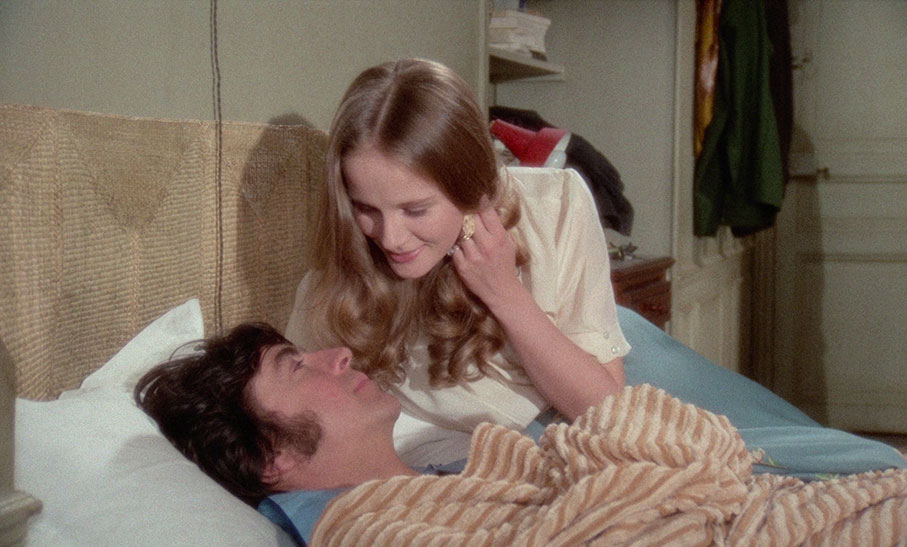

Which is correct? Well, here’s thing. Even after watching the original cut of the film twice, and a third time in its recut international version, I’m still not completely sure. It could be any one of them, a combination of all three, or even a complete fantasy or a misremembering of past events. The man’s name is Harry (Alan Bates), and in the very next scene he’s shown working busily at a typewriter with a small pile of notebooks at its side. In the spacious garden of his French countryside house, a group of children play, and as Harry gets up and puts on his jacket, he reflects on his years of married life in a foreign land, his three sons, and the question of what he should now do with his life. He then heads downstairs to join his American wife, Elizabeth (Evans Evans), and briefly assist with her preparations for a birthday party for their youngest son, Richard (Michael McVey). Once in the garden with the kids, the jovial Harry energetically holds court, but when called back to the kitchen by Elizabeth, this upbeat façade briefly falters, as his cheer visibly fades and he momentarily pauses his walk, his eyes closing briefly in a beautifully judged expression of suppressed unhappiness. Moments like this are why you hire actors of the calibre of Alan Bates. He brightens considerably at the arrival of the Cléo (Laurence de Monaghan), the beautiful young French girlfriend of his eldest son Adam (Sean Bury), and soon is back to merrily entertaining the children. With the assistance of his parents, young Richard blows out the candles on his cake and Harry merrily proclaims, “Now, everyone’s happy!” “Yes,” replies Elizabeth sardonically, “everyone’s happy.”

Then, without warning, we are transported to the plush country house of the wealthy TV executive Georges (Michel Auclair), as his domestic staff prepare the dining room for a formal dinner party and argue about the absence of asparagus, a foodstuff that Georges had the foresight to buy himself. When he enquires about the whereabouts of his wife, Natalie (Dominique Sanda), he is directed to the garden terrace, where she is dozing in a garden chair with a book on her lap. It’s immediately evident that she is the woman from the opening scene, and it’s quickly established that the two have a young daughter named Danielle. Natalie tells Georges that she knows that the dinner party guests are important but wishes they weren’t coming, prompting an expression of mild exasperation from her husband. “Were you up here all day?” he asks Natalie as she heads off to assist with the preparations, prompting her to pause and reply coldly, “Of course.”

Then, in what seems like mid-sentence, we’re back at Richard’s birthday party, where a wizard bird-dressed Harry leads the children into an old outbuilding to play the eagerly requested “cellar game,” a variant on hide-and-seek played in the dark. During the course of the activity, Harry finds himself in close proximity to Cléo, and despite their considerable age difference, the two are clearly attracted to each other, much to Adam’s considerable chagrin. His jealousy triggers a small but unfortunate chain of events that results in Cléo being electrocuted, knocking her cold and triggering bodily convulsions. A startled Harry quickly responds by administering some of the worst mouth-to-mouth resuscitation I’ve ever seen, and when Elizabeth arrives, she angrily berates him. “Why, why do you do it?” she barks before rushing off to fetch a doctor.

Before we can discover more about Cléo’s fate, the scene cuts abruptly to a three-second shot of a clothed but soaking wet Harry collapsing onto a face-down and equally drenched Natalie on the shoreline to the sound of crashing waves. It’ll take a sharp eye – or a second viewing – to register the desperation in Harry’s body language and the anguish implied by Natalie turning her head sharply away and clutching at the wet sand beneath her. Then, just as suddenly, we’re back with Harry and Natalie in the brasserie, but dressed differently to how they were in the opening scene, indicating that this assignation is taking place on a different date to the first. Here, Harry is recounting to Natalie what happened to Cléo, a tale that clearly has Natalie enraptured. “She’s all right, then? She’s not…,” she asks worriedly, to which Harry replies correctively, “No, no, no, no, of course she’s not. That part of it’s only in the story.” Hang on a minute…

From this point, all bets are effectively off as the lines between fact, fiction, fantasy, memory, and premonition become sometimes invisibly blurred. Harry proves to be a most unreliable narrator who is drawing on his life and his experiences to shape the characters and narrative of a novel he seems frustratingly unable to get to grips with. The core factual elements appear to be his relationship with his family and his affair with the much younger Natalie, a passionate romance that increasingly risks toppling both of their marriages. Yet even here there are small doubts, and just occasionally we are subtly teased by the notion that Natalie herself may be a product of Harry’s wishful imagination. “My God, Harry,” says Natalie as this short sequence concludes, “I never know what’s true and what isn’t with you.” “Us,” replies Harry sincerely after a pause, “This is true.” “Is it?” Natalie responds, a question probably intended to be about the strength of their relationship that could just as easily be read as a realisation on her part that she may just be a character in Harry’s novel.

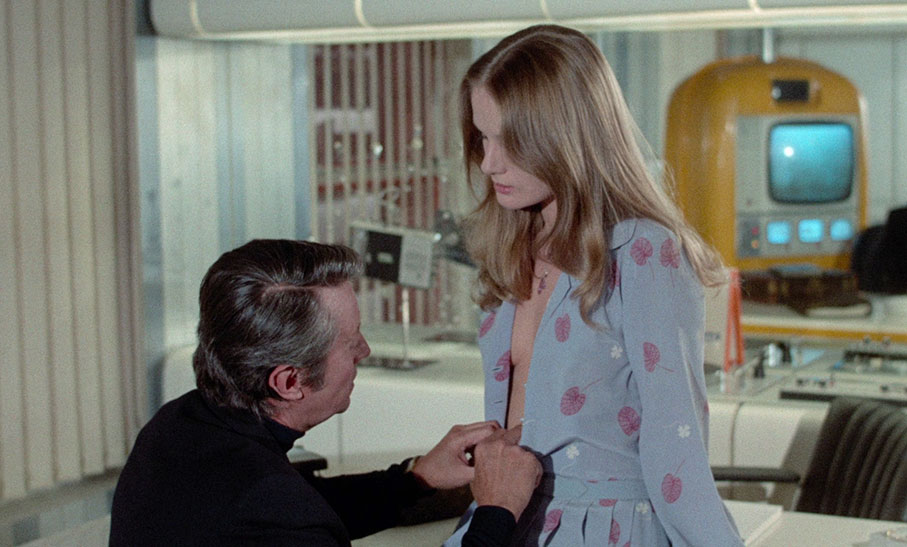

We are certainly invited to take scenes in which Harry plays no part at face value, notably when Georges has Natalie followed by a private detectives and later confronts her about her infidelity at the brasserie in which she and Harry regularly meet. But are we being shown what occurred or how Harry imagines events unfolded while he was off vacationing in Morocco with Elizabeth? This question is perhaps most pertinent when Natalie visits Georges at his workplace, whose decor looks like something out of A Clockwork Orange, jarring violently with the otherwise naturalistic settings. These scenes also give rise to an intriguingly offbeat sequence in which Harry is confronted by the two private detectives outside of the small Paris apartment he has rented as a place to meet and sleep with Natalie, under the guise of needing a place in the city to work on his novel without interruption. On being challenged, he mistakes the two detectives for policemen and has to pull off a bluff about having lost his keys to prevent them discovering that Natalie is waiting for him inside in a sequence that Tim Lucas in his commentary rightly labels Kafkaesque. Indeed, the two men – one (Vernon Dobtcheff) graced with an angular face and kitted out in a black overcoat and tie, the other (Henri Czarniak) a gruff, mackintosh-wearing heavy with an intimidating glare who lets his partner do most of the talking – look more like the secret police of a totalitarian state than low-key real world private detectives. Elsewhere, a comical encounter with an inept plumber and a tentative experiment at suicidal wrist-slashing – both of which take place in the Paris apartment – have the feel of episodes dreamt up by the struggling author, yet both trickle over into the scene that follows in which Elizabeth and his sons pay him an unexpected visit.

A bout of hypocritical jealousy on Harry’s part ultimately cuts the Moroccan holiday short, and as Elizabeth drives them away from the resort, Harry falls asleep in the passenger seat and the film takes a swan dive into surrealist dream imagery. It’s a visually striking sequence set in bright sunlight at a garden swimming pool surrounded by statuesque female nudes, and is peppered with people from Harry’s waking life. Here, Elizabeth dances trance-like with a young man she met in Morocco, Cléo reclines on a chiase-longue and mouths the line that she whispered to Harry in the cellar game, and Harry is seduced by the cheery and glamorous host, Hippolyta (Lea Massari), who is being pushed around by two topless muscle men in the manner of the mythical queen of her namesake. Initially in pig heaven, Harry is startled when he catches a glimpse of a shirtless Adam, and is dizzied by the sight of Natalie dancing unemotionally with an unidentified male partner. Eventually, he is led by Hippolyta to her bedchamber for his only truly satisfying sexual encounter in the film. Initially, he offers a vague resistance. “Perhaps I don’t want to be loved,” he tells his seducer, to which she responds with a smiling shrug, “No-one does. It’s easier to love than be loved.” Intriguingly, this locational switch is briefly interrupted by a return to the real world, where Harry is writing notes in a busy café, suggesting that what started as a dream composed of random imagery is developed – once the action moves into Hippolyta’s bedchamber – into a story under Harry’s direction. In that respect, his repeated references to himself throughout the film as God feels less like a delusional notion of self-importance than an admission of his role as the creator of this narrative.

Primarily adapted from his own highly regarded novel by Nicholas Mosley – before he was fired – the film was directed by John Frankenheimer at the tail end of a run of films that are still not widely championed to this day, shortly after he and his actress wife Evans Evans had – like Harry and Elizabeth in the film – made a home for themselves in France. On that score, the material has an inescapably autobiographical element (Frankenheimer, like Harry – and, indeed, the actor who plays him – was something of a philanderer), while as a director it sees him at his most experimental, with the Novelle Vague and French surrealist cinema key influences on this film’s style and structure. This is particularly evident in the non-linear aspects of the narrative, where future events are briefly glimpsed, like inspirational ideas being contemplated for later expansion in Harry’s novel. It took me a second viewing to pick up on all of them, particularly those that appear in a surrealistic sequence where Harry walks down a leafy pathway lined with identical and evenly-spaced black doorways, which stand unsupported like Kubrickian monoliths. As he intermittently stops to open and look though individual doors at himself interacting with others, I initially assumed he was recalling past events, but a second viewing confirms them instead as predictions, possible story threads in the narrative of Harry’s life.

This predictive element is also sometimes reflected in the dialogue. Early on, Harry claims to Natalie that “People like an unhappy ending,” to which she responds almost sorrowfully, “I don’t,” a moment that has considerably more impact the second time around. Much later, Harry flips this on its head by claiming that she doesn’t like happy endings, which prompts the telling response, “It was you who made it unhappy.” This kicks off a final half-hour in which the authorship of the story is unexpectedly transferred to Natalie, and it’s here that the film finds its true emotional feet. I’m not going to get into what unfolds here, but it builds to a superbly shot sequence in which several of the actors – including several children – are placed in a situation that looks genuinely dangerous, making me wonder how the hell it was filmed and just how much risk was actually involved. Major props here to a cast that clearly trusted the director, and to Frankenheimer and top cinematographer Claude Renoir for so convincingly creating such a nail-chewing illusion.

My first viewing of Impossible Object left me intrigued but not completely sure how I felt about a narrative that repeatedly tickled the intellect but failed to engage me emotionally, at least until the tense climactic scene. But a second viewing of the French original and a viewing of the international version – the accurately but less poetically titled Story of a Love Story – made it clear just how intricately structured, how complex, and how artistically and intellectually stimulating a film this is. The lead players are a key factor here, with Bates perfect casting as Harry, while Dominic Sanda is quietly captivating as Natalie. Both are impressively unabashed in their nudity (which for the most part does not feel remotely gratuitous), though it’s Sanda who goes the extra mile here, particularly when shown naked while genuinely pregnant, a single static shot that compresses an entire scene of exposition into a single expressive image. I’ll also give a shout to Evans Evans and Michel Auclair as the lead players’ spouses, neither of whom overplay the frustration and unhappiness they experience as a result of their faltering marriages and their suspicions about their respective partner’s infidelity.

For all my positive words, I’m not going to claim that Impossible Object is an overlooked masterpiece, but it definitely deserves far better than the near obscurity that circumstances conspired to consign it to. It’s definitely not a film to judge on a single viewing alone, and being able to watch both versions really bumped up my appreciation of a work that genuinely seems to get better every time I watch it. It was apparently not well reviewed in France on its initial release, being dismissed by some critics as Novelle Vague light, the work of an American director toying with techniques that French filmmakers had pioneered and already explored to greater effect. While I do get where they were coming from, for me it’s not that these elements feel or were intended to be revolutionary – what makes them work so well here is the effective use to which they are put and how seamlessly they are woven into the narrative. Retrospectively, the film also plays like a substantial taster for an even more complex, challenging and rewarding take on the same central concept from 1977, when writer David Mercer and director Alain Resnais collaborated on the extraordinary Providence. There’s a touch of irony to the fact that that the lead role in that film was played by Dirk Bogarde, the very actor that Impossible Object's orginal director Joseph Losey had wanted for the pivotal role of Harry, having worked with him previously on the 1967 Accident, which was adapted by Harold Pinter from a novel by none other than Nicholas Mosley.

Two alternative edits of the film have been included in this release, the original French theatrical version titled Impossible Object, and the international version titled Story of a Love Story. I’m not going to start listing all of the differences between the two cuts here, as that’s covered handsomely in the special features of this disc, primarily by the comparison featurette and Tim Lucas’s commentary track. Having watched both versions in quick succession, I was certainly aware of some of the more significant alterations, and like Tim Lucas, I found specific merit in both cuts, and was left secretly wishing there was a third version that combined the things l liked about them both into a single work.

In terms of the film’s structure and editing, I definitely prefer Impossible Object. Some of the alterations may be small but are often still significant, such as the insert of Harry in a café making notes midway through the surreal fantasy sequence. This is completely absent from Story of a Love Story, effectively rendering the scene in Hippolyta’s bedchamber as a continuation of the dream rather than an extension of it created by Harry. Far more impactful is the decision to open the film with the scene in which Harry is writing at his country home while the kids play in the garden, with the gallery sequence that opens Impossible Object truncated and delayed until Harry is established as a creator of stories, which can’t help but cast doubt on its authenticity from the off. This also messes with the original version’s beguiling symmetry, with the film starting and concluding (spoiler ahead – skip to the next paragraph to avoid) with a chance meeting between the same two people and opening and closing with the same line of dialogue.

Where Story of a Love Story does score is in the authenticity of its dialogue delivery. Both films are bilingual, with all conversations between French characters delivered in French in both cuts, while except for a few phrases, Harry speaks English in the international version, but flits between French and English in the French original. The thing is, the actors clearly spoke English in scenes with Harry and their dialogue was thus redubbed in French in post-production, and while I am reliably informed that the actors redubbed their own dialogue, the process still presents two potential barriers to complete engagement. The first is the usual problem with dubbing, that it results in a mismatch between the audible dialogue and what you can clearly see the characters saying. The second is a tad tricker for me to explain. For reasons I can’t be sure of, the pitch and tone of much of Bates’ delivery of his French dialogue is noticeably different to its English equivalent. This would not really matter if all of his dialogue had been dubbed into French, but it wasn’t, offering a model for immediate comparison that is audibly different enough to have me initially assuming that he had been dubbed by someone else. This, for me, has a distancing effect, and may well have been partly responsible for the uncertain reaction I had to the film the first time I watched it. Don’t get me wrong, the mix of French and English dialogue makes complete sense in the context of the story, but it feels more authentic in Story of a Love Story, where the actors deliver all of their lines in the language that they were speaking when the cameras were rolling.

The 1.66:1, 1080p transfer on Indicator’s Blu-ray was sourced from a 4K restoration from the original 35mm negative by Studiocanal, and the results are consistently impressive. Despite a sometimes filtered look that slightly softens the fine detail, the image is generally crisp and the detail well defined, and the contrast is very nicely balanced, with solid black levels that do not eat into shadow detail. I particularly liked the warm rendition of the pastel-leaning colour palette, which flatters the locations and helps create a seductive feel for the period in which the film was made and set. Film grain is visible throughout, and there are next to no traces of dust or wear.

The film’s original mono soundtrack has also been remastered and is presented as Linear PCM 1.0 on both versions, and although the tonal range is a little narrow when compared to modern works, the dialogue and Michel Legrand’s score are always clear and distortion-free, and I did not hear any obvious evidence of wear or damage.

Optional English subtitles are available for both versions when French dialogue is spoken. In addition, both include optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired.

Audio Commentary with Tim Lucas

Novelist and critic Tim Lucas delivers a compelling analysis of the film and its production, one littered with information that was new to me, and observations that both supported and occasionally presented intriguing alternatives to my own reading of what I had watched. Having not read Nicholas Mosley’s novel, I was particularly grateful for the detail provided on its content and structure, as well as the differences between it and the film. When it came to revelations, I was completely unaware of just how close John Frankenheimer came to being killed alongside his good friend Robert Kennedy when he was assassinated, or of the impact the man’s death subsequently had on him (it was a key factor in his decision to move to France). Detail is provided on the lead actors, and in a reflection of the film’s non-linear narrative, Lucas saves talking about the director and his career until we hit the final scenes. I’d love to have heard a little about how that hair-raising climactic sequence was shot (it’s quite possible that details on this are not available), but this is still an essential and informative listen.

Le Cinéma à…: John Frankenheimer (4:14)

An excerpt from the French television programme Le Cinéma à, which was broadcast on 13 May 1973 and recorded a month earlier during one of the first public screenings of Impossible Object. It opens with a pre-screening introduction by John Frankenheimer (the first 30 seconds of which is audio only), then moves on to an interview conducted with him and Nouvelle Vague filmmaker Jean-Gabriel Albicocco in what looks and sounds like a busy restaurant as the screening is close to concluding. Frankenheimer talks about the tension of waiting to see how an audience will respond to your film, while Albicocco suggests that you get a more balanced response from an audience that has paid to see it than you do from a private test screenings. After the film, Frankenheimer takes the stage to answer questions from the audience, provocatively asking them to identify the aspects of it they disliked, which does elicit two responses. Frankenheimer then replies to a more positive reading from a female audience member by telling her, “You perfectly understood the film, madame.” Unsurprisingly, the entire segment is conducted in French (a language in which Frankenheimer was fluent) with optional English subtitles.

These Obscure Subjects of Desire (13:20)

A video essay written and solemnly narrated by Daniel Kremer that compares Impossible Object to Sidney Lumet’s The Appointment (1969) as ‘lost’ films of the same period by two highly regarded directors, also exploring how both are about male self-delusion and the objectification of women. It’s an always interesting piece that is peppered with quotes from both filmmakers, plus one from Joseph Losey, whose plans to film Impossible Object were abandoned after a falling-out with the producer.

Stories of a Love Story (9:27)

The two versions of the films – Impossible Object and Story of a Love Story – are compared using clips, side-by-side comparisons of sequences that differ in each film, and textual detail on the specific changes made to the international version. I always really appreciate such inclusions, and even though watching both versions back-to-back enabled me to pick up on most of the differences this time, there were still a few here that I missed. As with previous such features on Indicator discs, this was written and edited by Michael Brooke.

There are two Image Galleries. Promotional Material contains 71 screens of promotional stills, a single lobby card, two posters and plenty of full page scans and close-ups of press book pages. Story of a Love Story Script Gallery has 41 screens featuring full page scans and close ups of the script for the first 38 minutes of the international version of the film.

Booklet

The lead essay here is by writer and filmmaker Adam Scovell, who kicks off by noting how unreliable a narrator Harry may be, then discusses the film’s production, its parallels with Joseph Losey's Accident (1967), and its cast and crew. This is followed by an equally enjoyable analysis of the international cut by artist, record producer and curator, Russell Haswell. He recalls seeing the film for the first time on TV in 1995, and is the first contributor to this release who appears to share my view that the early gallery scene involving Harry and Natalie may not be all it initially seems. Next is an article that focusses on author Nicholas Mosley, one rich with quotes and in which the production and the conflict of ideas that led to Mosley’s eventually dismissal from the film is explored. John Frankenheimer then discusses the film and its post-production fate in extracts from a range of articles from the 1970s and interviews conducted by Gerald Pratley for his 1998 book, The Films of John Frankenheimer. This is followed by a extract from one of the few contemporary reviews of the film and a couple of later re-evaluations. As ever, full credits for the film have been included, and the booklet is handsomely illustrated with promotional photos.

A fascinating work that quickly grew on me and that really does reward multiple viewings, which for me revealed subtle and clever foreshowing of events that I did not pick up on at all the first time around. An intelligent script, strong performances, and Frankenheimer’s confident direction mark this as a most worthwhile rediscovery from Indicator. As ever, the presentation and special features are of the highest calibre, and the inclusion of both cuts of the film is a major bonus. Warmly recommended, though it really made me want to see Providence again.

|