| "The most evil and perverted script I've ever read. It must never see the light of day." |

| Lord Brabourne on the screenplay for If.... |

| "It is the duty of the artist to bite the hand that feeds." |

| If.... director, Lindsay Anderson |

In Britain at least, the term 'public school' is a peculiar misnomer, at least in the form they exist today. Schools they may be, but public they are not. Some favour the term 'independent schools', but the American equivalent 'private schools' seems altogether more apt. They are, I have been assured by the few individuals I have known over the years who were educated at one of these elite (or should that be elitist?) establishments, worlds unto themselves. Here the offspring of the wealthy can receive a classical education, comfortably segregated from the working class plebs they are simultaneously being conditioned to rule and control. It's a notion that was neatly encapsulated by the American writer Ambrose Bierce, who in his 1911 publication The Devil's Dictionary, defined the word 'Distance' as "The only thing that the rich are willing for the poor to call theirs, and keep."

Public schools, of course, have given us some of our favourite writers, directors and comedians, but they've also helped create the likes of David Cameron, George Osborne, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage.* On that score alone, I'd say they have a lot to answer for. A public school background certainly opens doors, and has for almost as long as these establishments have been in existence. An art school acquaintance who experienced such an education certainly knew his way around Latin, Greek history and classical English literature, but he also had the common sense and world awareness of a cobwebbed breeze block. Rarely have I met someone less suited to lead or make high-level decisions, something even he seemed dimly aware of. Yet after dabbling drunkenly with fine art for a couple of years (and surviving a spectacular motorbike crash), he walked into a highly paid management position that was handed to him on a plate thanks to connections made back in school with well positioned families.

I think it would be fair to say that while If.... was probably not the first time I encountered the British (and let's face it, primarily English) public school system on film, it was the one that made the biggest and most long-lasting impression. I was well into my twenties before it occurred to me that just about every British film I'd watched on TV as a child in which schoolchildren featured was set in a public school, from the comedic antics of Will Hay's bumbling schoolmaster in Good Morning, Boys to the touching sentimentality of Goodbye Mr. Chips. The school life portrayed here was not one that bore any real resemblance to my own experience, but it didn't really matter. These were not documentaries, but fantasy narratives from a bygone era. But If.... was a different matter. From the opening scenes it felt disarmingly real, and I clearly remember one of those aforementioned acquaintances swearing to the accuracy of the film's depiction of public school life. He remembered his own schooldays with bitter resentment, and once claimed to me, when we were drinking one evening and letting a few home truths fly, that the homophobia I frequently berated him for had grown out of his anger at the sexual assaults he had suffered at the hands of the senior boys at the school.

But there was more. When I first encountered If.... I had only recently discovered the seductive wonders of surrealism, and had no idea at that innocent age that there were feature films out there with surrealist elements. And yet here was such a beast. And it wasn't a French or Spanish film from the 1930s, but a British commercial feature. Wow. This was my introduction to the cinema of Lindsay Anderson. I later caught up with This Sporting Life and O Lucky Man!, and was in London for the first week of Britannia Hospital. If.... and O Lucky Man! in particular proved a bonding agent with all of my close friends from film school onwards, every one of whom had seen both films and loved them. I'd go as far as to suggest that if I was magically able to gather all of the close friends that I subsequently made (and on occasion, lost) in a single place and could somehow persuade them to agree on just ten films, then those two would be in there.

Although this introduction is starting to ramble, a full review of the film is not required from me here, as the job has already been admirably handled by Camus in his detailed coverage of the previous Paramount DVD, which you can read here.

I will, however, add to his fine words to highlight a scene that stayed with me long after that momentous first viewing, specifically the unbroken and semi-improvised wide shot in which Mick, Johnny and Wallace wait outside the gym for their turn to be beaten. As Johnny and Wallace individually enter the gym, our apprehension is upped by the sounds that follow, a punishment we can hear but cannot see, and by staying with Mick until it is his turn to enter, Anderson cements our growing alliance with him. On paper this sequence shouldn't work as well as it does – wide shots are traditionally used to establish location before going in close to bond us to the emotional state of the character (that comes later, and how). But it works sublimely here, in part because Anderson places us in a situation we've all experienced to a certain degree. We may not have been caned by a trio of toffs, but who hasn't at one point in their young lives stood outside a door, or sat in a corridor, apprehensively waiting to enter a room where they will experience something they would rather avoid, whether it be a balling out for misbehaviour or a visit to the dentist that you've been forewarned is going to involve extensive drilling.**

Yet, in spite of my engagement, I was utterly bemused by the notion of a group of self-satisfied über-prefects who announce that they intend to beat a trio of unruly boys of similar age for their rebellious behaviour, and astonished that the boys just accept their punishment. If a prefect at my school had tried something like that he'd have eaten a knuckle sandwich. But here they not only take their beatings, which in Mick's case is extended to the point of barbarity, but they shake hands with their torturer and thank them afterwards. The first time I saw this my jaw hit the floor. For me this remains the point at which I absolutely knew, in my head and my heart, that the system that creates and enables such people, those who grow up believing in their own superiority and their right to govern others, needs to be torn down by any means necessary. By the time we reached the now famous climax, I absolutely knew which side I was on. Even as a teenager, I wanted to be up on the chapel roof with the Crusaders, Sten gun in hand, taking aim at an establishment and class system that continues to divide and conquer and suppress all hope of fairness and equality.

The anamorphic transfers on the previous US Criterion and UK Paramount DVDs were both impressive, and the HD transfer on the new Masters of Cinema Blu-ray shares many of their best qualities, particularly in the robust contrast and colour reproduction. You won't have to look far, however, for clear evidence of the upgrade in picture detail. When Rowntree orders Biles to take his golf clubs to his study in the opening scene, there is a box on left of screen bearing the logo 'Ancient Age'. Above and below this are words that you'll have to strain your eyes and make some educated guesses to accurately translate on the DVD, but on the Blu-ray there are crisply rendered and easy to read. This improvement is particularly visible in the wide shot of the chapel congregation at the climax of the film, where the increased detail on faces and clothing is immediately and most pleasingly apparent. The monochrome images are also well rendered, and only occasionally is a very faint flickering detectable. As you would expect, there is almost no sign of dust, damage or picture instability. Overall, an excellent job – I've not seen Criterion's own Blu-ray edition, but comparisons made elsewhere suggest the Masters of Cinema disc matches it on every score.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has some inevitable restriction of dynamic range, with a shallow bass response and some sharp trebles on the climactic gunfire. Dialogue is always clear and the organ music in particular is solidly reproduced. There is a faint background hiss, but you'll likely only pick up on it in the quietest scenes if you have the volume cranked up.

Optional English SDH subtitles are also available.

The extra features have been reviewed by Slarek, with the exception of the commentary and the short film Thursday's Children, which have been covered by Camus and reproduced from his review of the Paramount DVD.

Feature Commentary: Star, Malcolm McDowell and film critic and historian David Robinson (as a critic he was present at some of the filming of the movie)

This is a very good, informative and solid commentary. The 50-50 division between Robinson's and McDowell's contributions seems almost as if it must have been a cut and paste job but a few remarks tell you that the two men are there at the recording at the same time watching the movie. The fact it almost feels scripted is, in this case, a compliment. Robinson quotes "Intuition, pattern and convenience..." Lindsay Anderson's definitive answer on the arbitrary choices of one of the movies' most long standing arguments. Colour or black and white? And why? Let that be a final (three) word until the next time I bring it up.

McDowell – at 24 years of age, in his first film role – was quite happy for actress Christine Noonan to briefly appear wholly naked. But when it came to his own penis, Anderson apparently said "Help yourself!" and allowed McDowell to edit the one shot as it appears. He had no such qualms acting naked as a Frankenstein's monster in Britannia Hospital.

From recollection, Anderson comes across as a fascinating iconoclast with a withering opinion of those he saw beneath him (that would be all of us). He even directed McDowell on A Clockwork Orange, or rather before shooting (but no one told Stanley). But his talent and his unique position (he was sexually unreadable – assumed gay – read the Telegraph but was a committed anarchist) within the establishment and played up to this by taking acting roles that affirmed this lofty status and conveniently sloughing off his political intent. Like Chris Morris, even iconoclasts have to eat.

Interviews

Michael Medwin – Producer (4:17)

Medwin talks about getting the film off the ground, and Lindsay brusquely rejecting Charterhouse School as a filming location after their sixth formers told him that the script was rubbish. He confirms that the final draft of the script was almost exactly what was filmed, unlike Anderson's follow-up film O Lucky Man!, which Medwin claims aged him fifty years.

David Sherwin – Writer (4:46)

A dryly amusing interview in which screenwriter Sherwin talks about Albert Finney's involvement as uncredited producer, casting Robert Swann as the Chief Whip (who was apparently selected when producer Medwin said "God, that Robert Swann didn't half scare the shit out of me!"), and working with Anderson. The selection of how the title came about is revealed to be a suggestion by Albert Finney's secretary, "Then Lindsay came in and said, 'with four dots.'"

John Howlett – Writer (16:55)

Howlett recalls in compelling detail the process by which he and David Sherwin, who were at the same public school, wrote and developed the script for Crusaders, as it was originally titled, and why it took eight long years to bring it to the screen. I particularly liked his suggestion that exposure to films of the French nouvelle vague saw the script 'Godardified', and his telling choice of words when explaining their choice of subject matter: "We came swiftly to the conclusion that there was only one thing we should be writing about, and that was the strange institution from which we'd recently been liberated."

David Gladwell – Editor (13:19)

David Gladwell (who clears his throat frequently and at quite a volume) recalls first meeting Anderson, the process of becoming an editor, and eventually landing the job of editing If...., his first dramatic feature. He downplays his role as creative contributor with the claim that Anderson was standing over his shoulder for the entire process making the editing decisions, and even suggests his only real function was to physically operate the editing bench, which Anderson seemed reluctant to do.

Gavrik Losey – Production Manager (5:24)

Losey talks about the change in filmmaking style of the period from studio bound pictures to those shot entirely on location, and provides a brief overview of the pioneers of UK-based location lighting. He also suggests that Lindsay Anderson was not very fond of actors or the process of shooting films, and that what he really enjoyed was working on the edit.

Brian Harris – Camera Operator (2:23)

In a very brief chat, Harris talks about working with colour and black-and-white on the same film (always have a magazine of each ready at all times) and getting merry with Czech cinematographer Miroslav Ondříček at a Fulham football match.

David Wood – Johnny (Crusaders) (46:04)

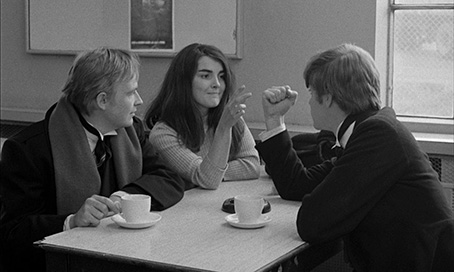

In what is far and away the longest interview here, actor David Wood discusses landing the role of Johnny and working on the film, all in engaging and anecdote-peppered detail. Topics covered include his first meeting with Anderson ("I've split my trousers!"), how he and his fellow Crusaders were prepped for their roles, the motorbike scene, the beating, the café sequence and a lot more. There's a lovely story about how Anderson managed to fool Wood and his fellow Crusaders into thinking they were improvising, while what he was actually doing was surreptitiously steering them to perform the script as written. He talks about the dummy script prepared solely to deceive the headmaster of Cheltenham College about the true content of the climax that they planned to shoot there, and apparently still has a ringing in his ears due to the noise of the gunfire.

Hugh Thomas – Denson (Whips) (4:32)

Thomas talks about landing the role (which he only knew he'd got when he was asked to come in for a costume fitting) and speaks briefly about filming the beating scene.

Geoffrey Chater – Chaplain (Staff) (7:53)

The now elderly Geoffrey Chater fondly recalls playing the role of school Chaplain "just slightly over the top" and discusses delivering the fiery sermon, the now famous drawer scene ("it seemed to have some symbolism, but no-one seemed to have a theory about what the symbolism was"), and shooting the final sequence. He also states that If.... was the most interesting film he has ever been in, and that he was not surprised that it won the awards it did.

Philip Begenal – Peanuts (Seniors) (9:01)

Begenal talks about the process of landing one of the film's most memorable support roles, playing the role of Peanuts, having his once spectacular teeth removed, how he landed at public school, how they are now full of the sons and daughters of money makers (you don't say), and the accuracy of the film's portrayal of public school life.

Sean Bury – Jute (Juniors) (4:13)

As with all of the other actors interviewed here, Bury talks about landing his role in the film, but also briefly covers being directed by Anderson, the atmosphere of freshness that pervaded the filming, and having his nipples pinched by Geoffrey Chater as the Chaplain.

Short Films

Three Installations (1952) (23:12)

An industrial documentary of the old school directed by Anderson, complete with a very British and fact-rattling narration (by Anderson himself), tripod-locked camerawork, stock background music, an absence of sync sound, and sequences that were clearly staged for the camera. The film outlines three mechanical installations and is designed to promote the engineering expertise of conveyer belt manufacturers Richard Sutcliffe Ltd, and is a product of their own film unit. The content will likely appeal primarily to those with an interest in industrial history, but it's really well shot in crisp monochrome by Walter Lassally, whose later work included A Taste of Honey, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Tom Jones, as well as the other two short films featured here. The camera operator was Desmond Davis, who went on to direct the decent version of Clash of the Titans.

Thursday's Children (22:08)

This is a black and white Oscar winning short (check out the BBFC's certificate, takes me right back) about a group of deaf children from Margate. Richard Burton – working for nothing, it's noted – provides the commentary and it's a caring and concerned look at (in my day in school certainly) the outcasts due simply to the fact they could not hear.

Henry (1955) (5:31)

A filmed appeal for the work of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children that focuses on a young boy who runs away from his home at night to escape his parents' bickering. Simple and to the point, the scenes with Henry wandering the busy streets of London have the invigorating look and feel of the Free Cinema work that Anderson pioneered with his friends Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson and Lorenza Mazzetti.

Trailers

U.S. Trailer 1 (3:00) is better than expected and concludes with the question, "Which side will you be on?" I think I've answered that. U.S. Trailer 2 (3:39) is the very same trailer, but concludes with a series of positive press quotes set to wretchedly inappropriate music, and finishes with the execrable tagline, "There's no if.... about If...."

Booklet

Lots going on in this excellent companion not just to the film, but the package in general. It includes a most entertaining new essay on the film by David Cairns; a brief piece by Cairns on the follow-up films, O Lucky Man! and Britannia Hospital; a useful and detailed interview with actor Brian Pettifer, who plays Biles, by David Cairns (he's been a busy fellow); a revealing 1968 article in which Lindsay Anderson interviews himself about the film; short pieces on Three Installations and Henry by Peter Hoskin, and Thursday's Children by Ros Cranston; film credits; stills; notes on viewing; and a fascinating poster pitching positive and negative quotes against each other in a manner that was to be recycled some years later by Lars von Trier to promote the then controversial Dancer in the Dark.

One of our all-time favourite films and one of the greatest calls to revolution ever commited to film looks better here than ever and boasts an excellent and comprehensive collection of extra features, more than you'll find on the Criterion disc, as it happens, making this THE version of the film to own. Marvellous stuff, and highly recommended.

* Odd though it may seem, David Cameron has apparently claimed that If.... is his all-time favourite British film. Read into that what you will.

** It is worth mentioning that this little masterstroke was put to even more stomach-knotting use by Stanley Kubrick back in 1960 in Spartacus, as Kirk Douglas and Woody Strode wait for their turn to fight in the arena for the amusement of a visiting dignitary (icily played by Laurence Olivier). Again Kubrick stays with our man and the preceding battle can be overheard but not clearly seen, encouraging us to focus on the faces of two men as they try to emotionally prepare themselves for a fight to the death.

|