|

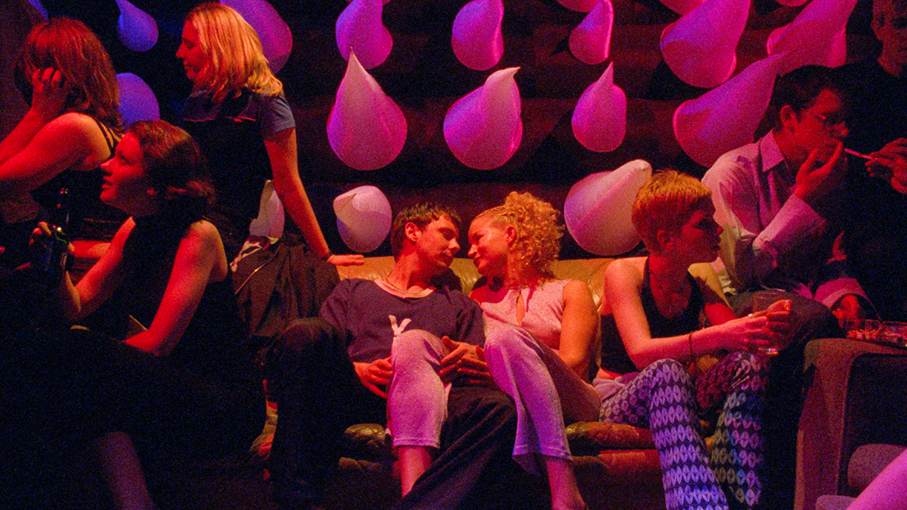

“You lucky, lucky people,” says Jip (John Simm) to camera at the start of Human Traffic. He’s stuck in a dead-end job (in one of the film’s several fantasy scenes, being literally shafted by his boss) and with what he describes as a monumental case of Mr Floppy. But it’s Friday and for the next forty-eight hours he’s going to ignore all that and get out of it with his friends in his Cardiff club of choice. Along for the ride are Nina (Nicola Reynolds), who has just walked out of a job she was being sexually harassed in, her sometimes jealous boyfriend Koop (Shaun Parkes) who is Jip’s best mate, Lulu (Lorraine Pilkington), Jip’s friend and dropping partner, and Moff (Danny Dyer), a transplanted Cockney, unemployed, a small-time drug dealer whose activities are unknown to his policeman father.

Human Traffic, made by and for twentysomethings very much au fait with the scene it depicts, was something new when it was released in British cinemas in 1999. It was a film that took notice of club culture, of young men and women spending their weekends spending their wages getting out of it and, yes, taking drugs to do so and having a good time on them. There were antecedents of course. Trainspotting, three years earlier, dealt with drugs and had a prominent musical soundtrack. But in that case, the drug was harder (heroin) and the comedown for some of the characters much worse, indeed sometimes fatal. In Human Traffic, while drugs are present you don’t actually see anyone take any. The most you have is someone cutting lines of cocaine on a glass table top. Whether or not writer/director Justin Kerrigan saw the film I don’t know (it had a limited cinema release in 1988 and had been released on video), but I was also reminded of the Australian film Dogs in Space in its concentration into a short period of time and place – Melbourne’s punk/”little band” scene of the late 1970s – its being a seemingly freeform ensemble piece, including Michael Hutchence in his best acting role, and the non-judgemental acknowledgement of drugs and their role in the characters’ lives. Needless to say, many older and more conservative people were appalled that a film like Human Traffic was playing in local cinemas across the country, even though youngster viewers would have to pretend to be over eighteen to be allowed in.

The film was made about a decade after acid house had come on the scene. Scare stories abounded in certain newspapers about illegal raves, often held in fields or other out-of-the-way places. In 1994, John Major’s Conservative government passed the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, which banned gatherings of more than ten people where music with “repetitive beats” was played, and gave the police powers to intercept and break up any raves they came across. The result was that the culture, fuelled by DJs who had become major names on the scene, moved indoors and into clubs, many of them large venues in big cities, such as the film’s fictional Asylum in Cardiff. Justin Kerrigan was a regular, often returning home and writing down the things he had seen and heard, and from that he developed the script of Human Traffic. While it’s clear whose side the film is on, we do hear the establishment view, with a doctor explaining that ecstasy acts as a serotonin suppressant and could lead to depression in later life, and that it causes overheating and excessive drinking of water is dangerous. (That was the cause of death of Leah Betts just after her eighteenth birthday, headline news in 1995.) However, this is countered by characters, especially Jip, advising that the number of deaths involving ecstasy is much fewer than those involving alcohol, and that’s a taxed and regulated drug that’s not the province of young people. Knowledge rather than scare tactics is the thing. And so on.

As writer and director, Kerrigan throws a lot at us, including fourth-wall breaks, fantasy interludes (including Howard Marks talking about “spliff politics” and the voice of Reality (Jo Brand) addressing Moff at one point), even a scene of a communal alternative national anthem complete with subtitled lyrics and a bouncing ball to help you sing along. Given that the cast is predominantly young – early to mid-twenties for the most part – it’s inevitable that there are several people who were just breaking through at the time and would go on to bigger things. Top-billed John Simm was among the oldest at twenty-eight when the film was shot, and was probably the biggest name. Human Traffic was his third feature film, but he had been on television since 1992, making an impression in the Jimmy McGovern-scripted series The Lakes, first series in 1997. This was Danny Dyer’s cinema debut at age twenty-one. As he was unwilling to put on a Welsh accent, his character was rewritten to be a Cockney, relocated to Cardiff due to his father’s promotion. (That’s also the reason why his line originally written as “Nice one, bra” became “Nice one, bruvva”.) Further down the cast, Jan Anderson, as Karen Benson, with whom Jip “fails his physical”, was a regular on Casualty at the time. And, after This Life and before Teachers and The Walking Dead, this was the fourth film for Andrew Lincoln, who like Simm had made his big-screen debut in 1995 in Boston Kickout. To date, Justin Kerrigan has directed only one more feature, I Know You Know (2008).

Kerrigan keeps the film moving at a fast clip, only slowing down as he needs to, when we reach Saturday and then Sunday and the film has a comedown along with its characters. Dialogue is well observed and often profane*. Inevitably what was up-to-the-minute at the time is now a period piece. People move on as no doubt the club scene has, and one generation has been replaced by the next. However, Human Traffic still stands up well a quarter-century later.

Human Traffic is released by the BFI in UHD and Blu-ray. This is a review of the latter format, which is encoded for Region B only. The film had an 18 certificate in the cinema and on homeviewing formats until 2002, but as of this year it was lowered to a 15.

The film was shot in 35mm colour and the transfer, in the intended ratio of 1.85:1, is derived from a 4K restoration from the original negatives. If the film is a capsule of its time and place, it’s also a capsule of its time from a technical perspective. This was a time when you would have seen this film projected from a 35mm print made up of six reels, a year or so too early for digital intermediates or digital projection (the earliest film I’m aware of having seen projected from a DCP was in 2000) and about a decade before digital capture became widespread to the point where it is now the main medium for making films instead of shooting on actual celluloid. Even though much of the film is set at night, this is an intentionally colourful film with those hues, especially reds, suitably vibrant. Blacks are solid and the grain looks filmlike. Although I didn’t see this in the cinema, this does look like what a fresh 35mm print would have if I had, before it picked up any wear and tear.

The original Dolby Digital soundtrack is rendered here as DTS-HD MA 5.1 and LPCM 2.0, the latter playing in surround. The surrounds are mostly used for music, with the subwoofer helping out with the bass in the club scenes. Otherwise, there’s not much to choose between the two tracks. English subtitles for the hard of hearing are available on the feature only. I spotted one typo: “base line” for “bass line” nine minutes in. It may say something about the subtitler’s music background that he or she identifies all the rave tracks on the soundtrack but doesn’t with an older disco track, Indeep’s “Last Night a D.J. Saved My Life” from 1982, which features notably in one scene.

Commentary by Mark Searby

For this newly-recorded commentary, Mark Searby begins and ends by laying out his credentials: he’s a critic but was also a DJ for twenty years, worked in a record shop and was an old-skool raver. As he points out, the film is as authentic as was possible to be. He begins by filling in the background of the rave and club scene beginning in the late 1980s, leading up to the passing of the Criminal Justice Act and the banning of outdoor raves and the founding of the club culture we see in Human Traffic. Searby also recommends other films about the subject, including Doug Liman’s Go from the same year, Mia Hansen-Løve’s Eden (2014), inspired by her DJ brother and co-writer Sven’s life, and even Kevin and Perry Go Large (2000). He also discusses the film’s critical reception, with the surprising revelation that The Guardian’s then-thirtysomething Peter Bradshaw seemed to get the film more than Empire’s presumably younger critic did, when you’d expect the opposite. A critic who certainly didn’t get the film was Roger Ebert, though as the film was re-edited for US release (removing many of the Britishisms and references like Richard and Judy in the process) he didn’t see the same version as Bradshaw. Searby also points out some of the soon-to-be-better-known names in small roles, including director Justin Kerrigan’s uncredited bit. There’s a little too much simple description of what’s on screen, but there’s useful information to be had. It’s a commentary from someone who is or was an insider on this scene, if not the same part of the country at the time, and as such it’s worthwhile. He ends the commentary by saying that Human Traffic is the best British film ever made.

Show Me the Money (19:12)

Executive producer Renata S. Aly begins by saying that she didn’t go to film school but broke in to the industry at the ground floor. Much of her role was raising finance. She read the Human Traffic script, which she saw as an accurate view of the scene and culture she was familiar with. Aly acknowledged that the film might not be an easy sell, given its lack of narrative structure and sensitive subject matter, particularly the use of drugs. She tells us that on her first visit to the set, Danny Dyer liked her yellow-lens glasses. When the film was finished, Madonna asked to see it.

Nice One Bruvva (14:09)

Mark Searby again, also newly-shot for this release. Inevitably, this overlaps somewhat with his commentary, though here what he says is illustrated with clips from the film. He talks about how Justin Kerrigan originated the script and this film, and the film (and the two-CD soundtrack album) are structured like a night out, the speed of the beats increasing as the night goes on, before a comedown kicks in. Again, Searby gives his credentials for saying that the film is entirely authentic and almost like a documentary.

Danny Dyer in Conversation (69:23)

A video recording from the BFI Southbank in 2023, with Danny Dyer interviewed by Nia Childs. If you thought the film was sweary, Dyer here rivals it relative to running time. He says that he is glad to be doing something he loves, and being able to make a living for it, though he is the first to say he has “made a lot of shit”. A weekend drama club led to a meeting with a casting agent and an audition for the role of what was then called a rent boy in Prime Suspect 3 (1993), broadcast when he was sixteen. He does say that David Thewlis, playing his pimp, was “a bit method” in their scenes together. As for Human Traffic, he says that there were plans for a Human Traffic 2, but then Covid hit. (Justin Kerrigan has since denied that there will ever be a sequel.) He auditioned for the play Celebration, by Harold Pinter, without having heard of the great man, and played a waiter in the original production in 2000. He worked with Pinter several times since, though confesses that while he might have acted in No Man’s Land, he didn’t understand a word of it. He acted in The Dumb Waiter during time out from Eastenders, in which be was in 1178 episodes over ten years. He also talks about his work with Nick Love, starting with The Football Factory (2004), which he compares unfavourably with Green Street (2005), the other film about football hooliganism from around the same time, starring a less-than-convincing Elijah Wood. He also acknowledges Gillian Anderson (with whom he worked in Straightheads (2007)) putting in a word for him, which resulted in his acting opposite Ray Winstone in All in the Game (2006) and dyeing his hair ginger.

As usual in these Q&As, relevant clips from film and TV are shown. While we see an extract from Human Traffic, clips from Prime Suspect 3 and The Football Factory are edited out. Questions from the audience, starting at 62 minutes, are displayed as onscreen captions before we see and hear Dyer’s answers.

Rave (11:37)

A short documentary from 1997, directed by Torstein Grude. In between shots of clubs in action, we hear from three people. Paul aka DJ Mack, aged twenty-eight, Adrian, the same age, a “techno tourist” who travels round Europe in search of raves, and Sarah, twenty-one, a raver who has been on the scene for four years at this point. She tells us about what it is like to take ecstasy, that it’s a halfway point on the spectrum from stimulants like cocaine to psychedelics like LSD. As with the main feature, we do hear the words of the establishment in the form of text captions and scare-story newspaper cuttings, but they are countered by the three interviewees. It’s quite significant that at one point someone spraypaints a K and a W to the beginning and end of the final word of the anti-drugs slogan JUST SAY NO.

Deleted Scenes (22:23)

A selection of scenes not in the final version of the film, presented in 1.33:1 letterboxed, with timecodes in the black bars. As usual with these things, you can see why they were taken out, as they would have added very little, padding out even such a loosely-wound film as Human Traffic. We have more of Jo Brand as “Reality”, seeing her (in a wig) onscreen rather than just hearing her voice, and with other characters than Moff on her couch.

Human Traffic pop promo (3:55)

As it says, featuring John Simm. This presumably played in cinemas as an alternative to the trailer. It’s presented in 1.37:1 but letterboxed into 1.85:1, so that the projectors of commercial screens could show it, though the bars top and bottom are yellow rather than black.

1999 trailer (1:34)

2025 trailer (1:21)

The original trailer emphasises the music and clubbing aspects, given that this was a new film by an unknown director and mostly then-unknown actors. The reissue trailer (available with DTS 5.1 and 2.0 soundtrack options) has the advantage of the film’s reputation, so we have some critical quotes, including the one from The Guardian calling it “the last great movie of the 1990s”.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release, runs to twenty-four pages plus covers. Following a warning of possible spoilers, it begins with “How Human Traffic Brought Rave to the Big Screen” by Lou Thomas. He begins by saying that every choice in art is political, and by making a film about rave and club culture, Justin Kerrigan was making a statement that this subject matter is worth viewing. And that’s a mindset that all that matters are “mates, music and anything but work”. Thomas makes the point that it’s clear whose side the film is on – that of the clubbers, not the authorities behind the 1994 Criminal Justice Act, protests against which feature in archive footage during the opening credits, with police attacking rioters. Thomas says that the film is honest about the reasons people on this scene take drugs and for the most part have a good time on them. This made the film a hard sell at the time: it’s a film involving drug use where no one dies. Thomas then discusses the film’s actors, beginning with Danny Dyer, then moving on to John Simm, who was the best-known name in the cast at the time. Although, especially following Trainspotting three years earlier, normalised drugtaking and music-heavy soundtracks weren’t unknown in British cinema of the time, but Human Traffic still stood apart from the social-realist fare and post-Four Weddings romantic comedies then being made. Thomas says that while there have been some exceptional clubbing scenes in films, but relatively few where the scene is the focus, and fewer good ones. Other than Human Traffic, he names just two: Eden, and the Scottish film Beats from 2019.

Renata S. Aly is next, with “Human Traffic, 25 Years On, Still Raving, Still Relevant” She says that the film is “the most unfiltered love letter to British dance music culture” and suggests that it still speaks to later generations struggling with coming of age and political disharmony. The soundtrack is genre-defining and the film’s visual style anticipates today’s meme and TikTok culture. Granted that she is hardly unbiased, being the film’s executive producer, her points are well made.

After a cast and crew listing, we have “One Nation Under a House Groove” by Tim Murray. He waxes nostalgic for a scene which may seem quite alien to Gen Z clubbers: a time where there were no smartphones and few mobiles, and the most you could do was text someone. The rise of dance music, starting with acid house in the late 1980s, was reflected in the large number of magazines devoted to the scene. Murray quotes several DJs and clubbers who were around at the time, and in some cases saw the film then. The scene had become mainstream, with the years 1999 to 2005 being the last of it as “progressing and feeling dangerous”, hedonism rather than idealism. “And we’re still here with all our marbles” says Terry Farley, then and now a DJ.

Also in the booklet are notes on and credits for the extras, and several stills.

Maybe you were there or maybe you weren’t. (I wasn’t, never being on the club scene and about ten years too old at the time.) Maybe you were too young for the time and place that Human Traffic captures. However, the film remains, looking and sounding very good in a new 4K restoration, and that’s what available on the BFI’s disc.

* At the time of writing, Human Traffic is 152nd in Wikipedia’s list of Films That Most Frequently Use the Word Fuck (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_films_that_most_frequently_use_the_word_fuck) with 174 uses in 99 minutes. That’s a rate of 1.76 fucks per minute, just in case any horses out there are liable to be frightened.

|