Note: This disc is only available at present as part of Eureka's Fuller at Fox, Five Films 1951-1957 box set.

Strange as it may now seem, there was a time when Samuel Fuller was not as critically revered as he has since become, though those who did admire his work tended to be passionate about it. I had personal experience of this, having attended an on-stage interview with the man at London's National Film Theatre as a 21-year-old film student, and the empty seats outnumbered the attendees by something like 5 to 1, possibly more. Yet those of us in attendance were genuinely thrilled to be seated just a few feet from a filmmaker we greatly admired, and hands aplenty shot skyward when the time came for him to answer questions from the audience.

Back then, films like House of Bamboo tended not to be taken that seriously by many in the critical fraternity. Its detractors tend to have the same complaints, that the Japan setting is irrelevant, that indigenous Yakuza gangsters don't even get a mention, and that the concept of a group of ex-American servicemen running rackets on Japanese soil behind the front of pachinko parlour management is impossibly far-fetched. These factors, they inferred, rendered any other qualities largely irrelevant. I and many others since would beg to differ. A gripping, hard-boiled and noir-tinted thriller in its own right, House of Bamboo is also a fascinating barometer of western attitudes to Japan in the post-war years, one whose plot and characters are nowhere near as fanciful as some have suggested and whose daring subtext clearly flew under the radar of contemporary critical evaluation.

In mid-50s Tokyo, a train is hijacked and a consignment of arms is stolen in a robbery that leaves an American army sergeant dead. Five weeks later, a man named Webber is injured whilst participating in a factory payroll robbery and instead of picking him up, his fellow gang members shoot him and leave him for dead. What piques the interest of the investigators is that the bullets they pull out of Webber match those in the body of the murdered army sergeant. The fact that he is an American civilian and former soldier also catches their attention, as does the fact that he has a Japanese wife named Mariko and a letter from an old army buddy named Eddie Spannier, who has just been released from prison and is apparently planning to pay Webber a visit. He's nothing to do with this, Webber assures them, and dies before they get anything useful out of him.

Three weeks later the aforementioned Eddie (Robert Stack) steps off of a frieghter from San Francisco and hits the streets of Tokyo, dressed in an ill-fitting raincoat and sporting an attitude. He goes looking for Webber and only learns that he is dead when he chases and confronts the frightened Mariko (Shirley Yamaguchi), who seems as surpised as Eddie that her husband would have got involved in a robbery. Eddie then takes his attitude and uses it to lean on local pachinko parlour managers for protection money. He doesn't get far. He's only on his second such threat when he is thrown through to the feet of Sandy Dawson (Robert Ryan), the head of a gang made up of former dishonourably discharged American ex-servicemen that runs a sizeable number of the city's pachinko arcades, which serve as a front for their criminal activities. Impressed by Eddie's shady history, Sandy takes a liking to him and persuades him to join his organisation, unaware that the surly Eddie is not quite what he seems.

The first post-war American feature to be shot on location in Japan, House of Bamboo does sometimes present us with a tourists'-eye view of Tokyo, with reality doctored to conform to a 1950s American view of how Japan should look. Thus almost every female character is dressed in a kimono, Mount Fuji and Kamakura's Daibutsu (giant Buddha) are prominently featured, and walls and shops are plastered with signs that sometimes make no literary sense, kanji characters selected for their visual appeal rather than their meaning. But the location shooting also captures a snapshot of reality that would simply not have been present in a US-based production. These include the western hairstyles being sported by local women already developing a taste for all things American, early signs of the country's economic and industrial recovery, and main streets that are startlingly light on traffic, at least when compared to modern day Japan. And it's always good to hear actual Japanese spoken instead of comically accented English, even if it is largely confined to the background characters.

Made just ten years after the end of World War 2 and only three years after official US occupation ended, the film also works as a reflection of America's (and Japan's, as it happens) evolving but still uncertain attitude to mixed race relationships. Eddie's evolving romantic and (we presume) sexual involvement with Mariko and her former marriage to Webber had its real-life equivalent in the GIs stationed in Japan who had relationships with and in many cases married local girls, but this was still largely uncharted territory in American movies (Joshua Logan's prejudice-busting Sayonara was still two-years off). It's something Yamaguchi's slightly western looks and accent and word-perfect English (she had been living in America for four years when Fuller cast her as Mariko) were likely a concession to. The film also captures the local hostility to such relationships, with Mariko subsequently shunned by her immediate neighbours, a prejudice you'll still find traces of in present-day Japan.

The concept of a group of American gangsters running pachinko parlours has come in for particular scorn, and while I'll accept that the notion is a little fanciful, it is worth noting that in post-war Japan the pachinko arcades were largely under Chinese or Korean ownership, and their link to organised crime is the stuff of local legend. I'm not aware of evidence that gangland America had a stake in this business, but given that many of these parlours were indeed under foreign criminal control, in the 'what if' stakes this is perhaps not as far-fetched as some have suggested.

Not every aspect of the film is specific to the time it was made. Eddie's embarrassment at the whole Japanese bathing experience is something I've observed more than once as westerners encounter their first onsen bath, and his attempt to communicate with locals by irritably speaking English slowly and loudly remains a depressingly common trait of lazier western tourists. And in the present world situation you can read what you like into the concept of ex-members of an occupying army exploiting the local population in the pursuit of unprincipled profit.

Where the film walks an interesting and potentially risky path for its day is in a homoerotic subtext that strongly suggests that Sandy hires Eddie not for his criminal skills but for the simple reason that he is attracted to him. Mock the notion if you like, but the indicators are everywhere, in Sandy's protective attitude to Eddie when he's injured, in the ferocious jealousy of his current ichiban Griff (Cameron Mitchell), and in the conspicuous lack of a female companion that by then had long been a gang-boss standard for American crime films. It's even visible in the manner in which Eddie is sometimes positioned and dressed – that he wearing a yukata (a casual kimono) in one scene is not in any way unusual in Japan, but that he at one point is shown lounging casually in one when his fellow gang members are dressed in suits does feel like it's subtly trying to tell us something. As it happens, Fuller has confirmed that this was indeed very much part of his game plan, revealing also that only Robert Ryan cottoned on to this and that having done so started to incorporate small signals into his performance from this point on.

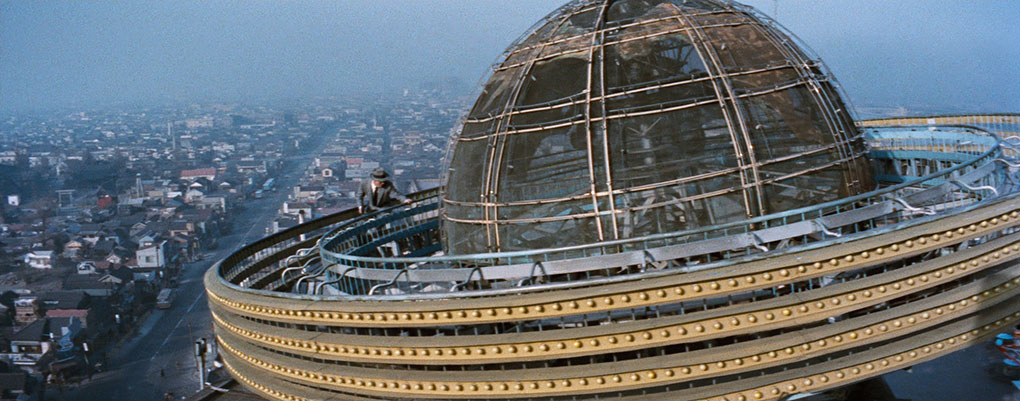

Ultimately, however, House of Bamboo lives or dies not by its social subtext but by its effectiveness as a crime thriller, and although a partial remake of William Keighley's 1948 The Street with No Name, it delivers on all fronts. Fuller's brisk pacing, his confident use of camera movements and extraordinary organisation of characters in frame, coupled with Joe MacDonald's frequently gorgeous CinemaScope compositions and Robert Ryan's deliciously judged turn as the cool but deadly Sandy Dawson, invigorate the story and charge it with the sort of fat-free energy that gave so many of Fuller's movies the edge over their bigger-budgeted brethren. And Fuller's distinctive stamp is evident throughout, from the unflinching brutality of Dawson's justice to the thrillingly executed tracking shot as the gang flee a robbery and an audacious climactic high-rise funfair shoot-out. House of Bamboo may not quite be Fuller and his most experimental or boundary-pushing, but it's still a riveting drama whose location shooting and multi-layered socio-political subject alone make it essential viewing.

Sourced, as far as I'm aware, from a 2K restoration by Fox, the 2.55:1 1080p transfer here is rather lovely, with a vibrant reproduction of the film's rich colour palette, well-balanced contrast in the daylight scenes and clearly rendered night-time sequences in which the shadows are jet black and the lit areas are always clearly visible. Detail is consistently crisp and the image is surgically clean and free of damage, and a very fine film grain is visible throughout. The transfer on the earlier Optimum DVD was a good one, but this leaves it standing.

The film's original 4-track stereo soundtrack is the basis for the Linear PCM 2.0 stereo track here. Dialogue, music and ambient sound are all cleanly rendered, and while there's no real punch to the bass, this is still sonically superior to many later films. The separation is also more subtly rendered than on the previous Optimum DVD. There's no trace of underlying wear and no background fluff or hiss.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary by Film Historians Julie Kirgo and Nick Redman

Listening to the soft-voiced Nick Redman talk about film is always a pleasure, but here he often takes a back seat to the effusive Julie Kirgo, who admits up front that House of Bamboo is one of her favourite films. Both are clearly huge fans and can get a little carried away with reading things into elements that may actually have a more straightforward reason for being (this is especially true of the climax), but still do a great job of highlighting and deconstructing the more exceptional compositions and sequences, as well as the film's homoerotic subtext. Robert Stack gets a mention but it's Robert Ryan that they're most captivated by and with good reason, though there is also some discussion about supporting players Cameron Mitchell and Brad Dexter and producer Buddy Adler. Lots more is discussed, all of it interesting, though I was a little surprised to hear that neither Kirgo nor Redman seemed to know exactly what pachinko is.

Audio Commentary by Film Historians Alain Silver and James Ursini

And if you were somehow worried that Redman and Kirgo hadn't covered every aspect of the film in detail (they pretty much did), we're gifted with a second commentary from film historians Alain Silver and James Ursini, who signal up front that they are likely to be a little more tempered in their assessment by describing House of Bamboo as "one of the better films by Sam Fuller." Similar ground is covered here but from a different perspective, including the composition and arrangement of characters in group shots, the influence of Japanese cinema of the day, and, of course, the homoerotic subtext. A story told in the previous commentary that I just didn't buy about how one scene was shot is repeated here, but I was put right on this by information in the extra that follows. A solid commentary and of very real interest, even if it does lack the unbridled passion of the Redman-Kirgo one.

Fuller at Fox (26:17)

While always worth watching, some video essays by David Cairns can be a tad esoteric, but this one should be considered essential viewing, providing as it does a fascinating overview of the five Fuller films in this set. Hell and High Water is given short shrift in order to get to the films that Cairns clearly prefers, and the essay is peppered with information not provided by other extras on this disc, including quotes from Fuller that are read out by his daughter Samantha. It's one of these that stopped me making a prat of myself by dismissing a claim made in the commentaries that a sequence in which Robert Stack's character is roughed up by locals was done for real after the assistant director told shouted out that he was a thief. The mere fact that these locals then march Stack up to the police station door, where a sizeable CinemaScope camera that none of them look at tracks forward while they stand each side of the ruffled Stack in a compositionally helpful manner, made the whole idea seem unlikely to me. Here, however, a quote from Fuller reveals that they shot the scene initially with hidden cameras, then revealed to the locals that they were making a movie and asked them to repeat their actions for a second take, which they apparently did with considerable enthusiasm. I stand happily corrected. Cairns also wonderfully sums up the appeal of Fuller's work when he says: "Fuller was a man who liked to talk, and his movies grab you by the lapels and yell in your face." Outstanding.

Trailer (2:19)

A standard definition trailer with excitable narration and lots of action and intrigue, though it does give away the half-hour-in plot twist that I've uncharacteristically chosen not to discuss.

Booklet

As this is part of the five-film Fuller at Fox: Five Films 1951-1957 box set, the booklet covers all of the films, but handily does so in separate chapters. The relevant section here kicks off with a detailed essay by Richard Combs on House of Bamboo and Fuller's 1957 China Gate, and it makes for fascinating reading even if you are familiar with both films. Up next is a piece by Fuller himself on the making of the film, his experience in Japan and the decision to include a homoerotic subtext. It also includes the passage that was read out in the Cairns documentary that put me straight about the scene where Robert Stack is roughed up, plus a few other stories from the shoot. A hugely enjoyable read. Credits for the film have also been included.

A damned fine Fuller film that I was initially drawn to as much by its setting as its director and that just seems to get better with every viewing. Part of that comes from my certainty that the subtext failed to register at all when I first saw it back in my late teens and that later viewings have helped to peel back the surface layers and allowed me to more fully appreciate the skill and creativity of the filmmaking. This is as good as I've seen the film look, and you get two audio commentaries, a fine video essay and a solid chapter in the box set booklet. If this was a stand-alone release I'd be heartily recommending it, but it's also one of several compelling reasons to get your hands on this box set.

|