|

At a time when you can even shoot 4K video on your smartphone, it's easy to forget how revolutionary the arrival of the mini-DV tape format was for amateur and semi-professional videographers. Affordable and compact, the definition and quality of its imagery clearly eclipsed its immediate predecessors SVHS and Hi-8. More crucially, it was a digital format, and coinciding as it did with the arrival of low-cost, computer-based editing systems like Adobe Premiere and Apple's Final Cut Pro, it allowed even non-professional users to edit multiple sound and video tracks, to easily add effects and fancy transitions, and to output their finished work at the same quality at which it was captured. It really was a bit of a game-changer in its day.

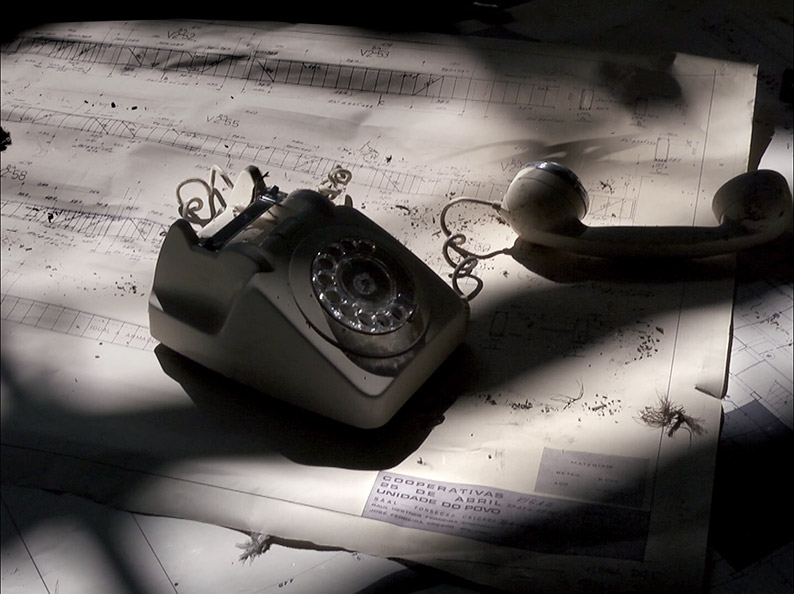

Only after the dust had settled did we begin to appreciate that it was never going to seriously compete with film or high-end video formats, but it still had its day in the cinema sun. The Dogme 95 group embraced it and made a virtue of its limitations, and companies like Sony, Canon and Panasonic produced professional level cameras that were designed to get the very best out of the format. Using a Canon XL1s, British born and Copenhagen based cinematographer Anthony Dodd Mantel worked small wonders with the format for Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later, a major release whose reduced definition and burned-out highlights the audience seemed to take in their stride. This, I figured, was as good as this particular digital format could ever look. Then I saw Portuguese director Pedro Costa's 2006 Colossal Youth. On my first viewing I knew next to nothing about the film's technical production – it was obvious to me from the opening frames that it was a digitally shot feature, but rarely had I seen digital imagery look as beautiful as it did here. Only later did I discover that the film was shot entirely on mini-DV on a Panasonic DVX100 and lit primarily using daylight and carefully positioned reflectors. The DVX100, it should be noted, proved was the camera of choice for a number of low-budget filmmakers in its day, primarily for its ability to capture 'film-like' imagery in 24p (the same frame rate as film), though given that HD is still struggling to do likewise, such a claim has to be taken with a small pinch of salt. Indeed, I would suggest that what Costa and his co-cinematographer Leonardo Simões achieved was not film-like at all, but a uniquely and visually arresting digital aesthetic, one as important to the tone and storytelling of the film as the performances, locations and the deliberate pacing of Pedro Marques' editing.

Despite the current ubiquity of HD as the low budget video format of choice, Costa and Simões chose to stick with the DVX100 for their 2014 follow-up feature, Horse Money, and the results are every bit as visually ravishing. Tonally, it's definitely a darker film, with none of the brighter urban exteriors that intermittently punctured the dark in Colossal Youth. Here, even at its brightest, daylight seems to struggle to penetrate the dimly lit corridors, soulless hospital rooms and even occasional exteriors in which the film is primarily set.

When talking about this film, Guardian critic Peter Bradshaw intriguingly described Costa as "the Samuel Beckett of film," which very neatly alludes to the challenges – as well as the pleasures – that Horse Money will likely present for the unprepared newcomer. Even as someone who basked in the tonal and visual beauty and the seamless blend of fact and fiction of Colossal Youth, I struggled to completely comprehend what I had seen after my first viewing of Costa's follow-up up feature. Repeated attempts to kick start an already overdue review fell at the starting gate because I remained uncertain about how I was meant to interpret what I'd seen and heard. A second viewing helped, as did the interview with Pedro Costa included on this disc and some further research on Portugal's Carnation Revolution, but it was on my third viewing of the film that the mist finally cleared. Well, sort of. I'm still not sure of everything and remain convinced that there are a number of ways to interpret what unfolds, but a good many of the of things I was previously confused by were now beginning to come into focus.

What does become clear on subsequent viewings is that despite first impressions, the film does have a slight but visible narrative structure, one in which Costa favourite Ventura – ageing and slow moving, his hand trembling as the result of a disease caused by his living conditions (or, it is at one point suggested, the medication to treat it) – has been admitted to hospital in a poor state of health and during the process of his recovery looks back on his life, and reflects on how a popular revolution ultimately failed to positively impact on him or his friends and family.

From an early stage there is a sense that Ventura himself is time-slipping through his own life and memories. Questioned by an unseen doctor, he gives his age as 19 and 3 months and claims that he was brought to the hospital by the revolutionary army, yet seconds later acknowledges his actual age by identifying himself as a retired bricklayer. The initial suggestion is that the mould in the walls that has left him physically damaged has also started to affect his mind, and this remains one possible way to interpret what unfolds, with events portrayed entirely as they seem to Ventura as he wrestles with memories and the possible onset of senile dementia. Thus the dilapidated condition and gloom of basement corridors down which he repeatedly wanders may actually be visual expressions of his internal malaise.

Yet intermittently there are also small hints that Ventura may already have passed away and become trapped between two worlds in a place swathed in darkness and inhabited by ghosts, where time has no meaning and no longer follows a linear path. A number of sequences begin with Ventura lying motionless on his back, a death-like state from which he then slowly stirs, and on one such occasion he appears to have been physically transported to the site of a former workplace. Despite the size of the hospital (the canteen could sit a hundred people) he's rarely seen in the company of more than one person at a time, and in his first encounter with grieving widow Vitalina, he assures her that her husband is alive and here with him, wherever 'here' actually is, of course. Later he hands her a letter that he claims is from her husband, but from what we have intermittently observed it seems likely that it was written by Ventura himself. Is this the product of a confused mind, a well-meaning attempt to comfort an old friend, or a genuine message from the afterlife delivered by one still able to communicate with the living? Or is Ventura actually alive and alone and being visited by the ghosts of others from his past? Credence is leant to both of these interpretations when Vitalina drags up a dark memory from Ventura's past and tellingly assures him that he is on the road to perdition. Whether this is meant to be taken literally or as a figure of speech is left for us to decide.

On this very disc, Costa expresses a reluctance to provide specific historical context for his film, but I'd argue that without it whole conversations and encounters will remain at least partly opaque. There are, for instance, repeated references to the Carnation Revolution and more specifically how it ultimately failed the country's sizeable black population. Initially a point of oblique discussion between Ventura and those he meets in this hospital netherworld, it is later given full voice in a haunting sequence where a seemingly dazed Ventura, wandering darkened streets in his underwear and boots, is confronted by soldiers and an armoured car, prompting him to slowly raise his hands in confused surrender. It all comes to a head in a climactic sequence in which Ventura finds himself in an elevator with a living bronze statue of a revolutionary soldier, whose position shifts tellingly every time the camera cuts away and who is host to a string of voices from Ventura's past. Alternately mocking and berating him, these voices at one point dismiss his claim that he is of retirement age and suggest that his children have yet to be born, a further indication that here time does not follow a linear path, which is then emphasised by the spoken claim that "This is the story of the young life and of the life yet to come and of all the things that will follow."

The grim lot still facing those on the bottom rung of the Portuguese social ladder is summed up by the speech Ventura himself makes early in the film to visitors to his hospital bed when they talk of how things will be after the revolution. "Our life will still be hard," he assures them. "We'll keep falling from the third floor. We'll keep on being sliced by the machines. Our heads and lungs will continue hurting the same. We'll be burned. We'll go crazy. It's all that mould in the walls of our houses. We've always lived and died this way. This is our sickness." Later he finds himself in a factory in which he once worked, a building that was long ago stripped of anything of value by an owner who absconded with the firm's money and equipment and left the company and its employees to flounder. Here he encounters his godchild Benvindo, who has been waiting for his final paycheque for 23 years and has sobering stories to tell of those they once worked with, and is then seemingly transported back in time to a point where his own wages were drastically cut because of his young age, news delivered by a figure we only see in silhouetted outline through a frosted glass window.

Horse Money is a deeply melancholic but visually stunning (the screen grabs here don't come close to doing it justice) and haunting work of thoughtful, multi-layered and ultimately moving film poetry. It's not an easy film experience – many, even in the critical fraternity, have been left scratching their heads at what they have seen even on multiple viewings (see the accompanying booklet) – and Costa's use of long and primarily static shots, indirectly connected scenes and seemingly oblique exchanges require considerable patience, concentration and a little background knowledge to fully appreciate and effectively interpret. But for those willing to go where Costa wants to take you there are rewards here in abundance, artistic, intellectual and even emotional. And while like all films this should be a big screen experience, in some ways this disc is the perfect vessel for this remarkable film – watch it once and let the tone and content wash over you, then watch the Costa interview, read up on the Carnation Revolution, then come back to it and really appreciate the breadth and depth of what Costa has achieved here.

There are doubtless those out there – and until I watched this disc I was probably one of them – who would question the logic of releasing a film shot on standard definition video on a high definition disc, a particularly strange choice for a first Blu-ray release from a company who have done pretty damned well by DVD, you might think. Then again, as I made clear in my opening paragraphs, what Pedro Costa and Leonardo Simões can do with DV frankly leaves what many can achieve even with Ultra-HD standing, and their work is beautifully rendered here. Sure if you're looking for signs that this was not shot on HD or film then the 1.33:1 aspect ratio, the just slightly crispy edges when heads are framed against a bright window (only happens once) and a sharpness that if you lean in close is not quite 2K crisp are definite giveaways. But in all other respects the very fact that the film was shot on SD digital video beggars belief. The level of picture detail exceeds any SD image I've ever seen, and the contrast range (another usual SD weak spot) is gorgeously judged, with inky blacks, precious few of the obvious burnouts on highlights that 28 Days Later had to live with, and a generous tonal range in-between. So finely pitched is this balance here that when Vitalina is reading from documents relating to her and her husband's life and death, her dark skinned face effectively silhouetted against a wall of white light, you can still see the tear that runs from her left eye. The earthy colour scheme is also handsomely rendered, and I didn't see any trace of compression artefacts anywhere, damned good going for a format that could be prone to them even at the shooting stage.

When it comes to the soundtrack, you can choose between Linear PCM stereo and DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround. Both are crystal clear and boast a strong dynamic range, though rarely do their get to flex their muscles on this score (this is not that sort of film). The DTS track does make effective use of the surround speakers for ambient sound, which is more prominent in some locations than others. Music, rarely used here, sounds splendid on both tracks.

O nosso homen (2010) (25:15)

A short film made by Costa in 2010 in which Ventura converses with a homeless former bricklayer who lost his job and his social security, and was subsequently divorced by his wife. His attempts to hunt and catch animals for food fail to impress the more experienced hunter José, who is nursing a sheet of paper that looks set to shape negatively his own future. Shot in Costa's signature locked-down and exquisitely framed style, it's a gently paced and toned observational piece, a good half of which is set in the sort of sunlit exteriors you'll find little trace of in the darker Horse Money. It kicks off with an intriguing conversation between José and his mother about where she will live when she moves to Cape Verde, before moving on to a discussion on an urban legend about a man the mother describes as "terror itself," someone snares you by slipping a letter in your pocket, much in the way fatal curses are passed on in M.R. James' Casting the Runes.

Filmmaker Thom Andersen introduces Horse Money (5:09)

Anderson talks about the film's opening montage of photographs by Jacob Riis that recorded the lives of New York's late 19th Century tenement community, the effect they had on him and their role in the film. The sound quality is imperfect but clear enough, and plays under the sequence in question, which Costa himself echoes later in the film itself.

Pedro Costa in conversation with Laura Mulvey (40:53)

Introduced by none other than Mehelli Modi, the passionate driving force behind Second Run, Costa is here interviewed on stage by film theorist Laura Mulvey at a screening of the film at London's ICA cinema. And although covered in a single, unbroken wide shot, it's what Costa has to say that makes this such an essential and revealing companion to the film. I, for one, was enthralled to learn that his feature career almost began with a remake of the 1943 Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur horror classic I Walked with a Zombie, and this story becomes a springboard for a detailed history of how he fell in love with the district of Fontainhas and its people, why he switched from film to digital as a recording medium, and how Ventura – a man he describes as "very tall, very beautiful, very frightening" – went from being the best assistant he could ask for to his favourite leading man. He claims that you don't need to know about the Carnation Revolution to understand the film, but when pressed provides just the sort of information you'll need to start making sense of elements that may have previously flown over your head (that was certainly the case with me). There's plenty more here, all of it worth hearing. A fine extra feature.

Trailers

The UK Trailer (1:43) and the International Trailer (3:31) both consist of a montage of shots from the film set to the song around which Costa created his own mid-film montage – the international trailer is longer and the song lyrics are subtitled (as they are in the film itself). There are also 4 Teasers (0:30, 0:19, 0:29, 0:18), each consisting of carefully chosen shots matched to the climactic organ blast from the elevator sequence.

Booklet

Given that there are two detailed interpretations of the film and its content here, this is one extra I'd personally save until after those first couple of viewings, as they're likely to colour your own, possibly very different interpretation if read up front, which would rob the film of one of its key pleasures. Once you've formed your own opinion, however, both make for compelling reading. First up is a piece by Jonathan Romney that kicks off with a reflection on the difficulty of actually describing Horse Money, a challenge he then admirably rises to. This is followed by an equally impressive analysis of key aspects of the film by Chris Fujiwara, and is tailed by credits for the main feature and the on-disc extra features.

Horse Money is the sort of challenging cinema that it's genuinely exciting and deeply rewarding to be challenged by. Visually sumptuous in a manner that flies the flag for digital cinema from the highest flagpole, it's a haunting example of low-key political filmmaking at its minimalist best, and a deeply affecting meditation on memory, loss and the experience of societal marginalisation. What must on paper have seemed like an odd choice for the first Blu-ray release from Second Run is actually a triumph, with a belter of a transfer and spot-on extra features making this feel like a seriously complete package. Highly recommended.

|