|

I'm always impressed when a film is able to communicate key information about its characters and/or story in its opening shot, particularly when that that information is not loudly broadcast, and especially if the shot and the subject are both completely static. Take the first post-opening titles image from the 1973 British film The Hireling, a prize-winning but oddly underdiscussed work that I'll freely admit I'd never encountered before the Blu-ray release under discussion here. A woman named Helen (Sarah Miles), dressed in a dour-looking blouse, skirt and open cardigan and with slightly unkempt hair, stares motionlessly through a tall wire fence, her unchanging expression that of someone who is emotionally shattered. Some way behind her sits a large white building that could be a stately home, but somehow you suspect that it probably isn't. The shot runs for just four seconds before it cuts to the image of a barren tree branch reflected in water, which we can presume is the target of Helen's unbroken gaze.

Despite the brevity of this opening shot and the fact that I knew nothing about the film before I watched it, I was able to make a couple of confident assumptions about what I was seeing based purely on the framing, the lighting, the grading of the image, the look and expression of the woman, the height of the fence, and the shape and whiteness of the building behind her. In just four seconds I was convinced that Helen was a patient in a sanitorium and that she had experienced some kind of mental or emotional breakdown. Confirmation soon comes when a nurse emerges from the building's conservatory, simultaneously establishing Helen's social status and the period in which the film is set by calling out for Lady Franklin and sporting the sort of headgear that was abandoned by the nursing profession a couple of decades before this film was made. When the nurse crosses the grounds to meet the still lost-looking Helen, she reminds her that Doctor Mercer (Lyndon Brook) is waiting to see her, and also that she is leaving the sanitorium today, words that Helen vacantly repeats until she reaches the bit about her imminent departure, the timing of which seems to both confuse and surprise her. As the nurse steers another, even more confused patient back towards the hospital, I found myself wondering if the decision to send Helen home was perhaps just a trifle premature.

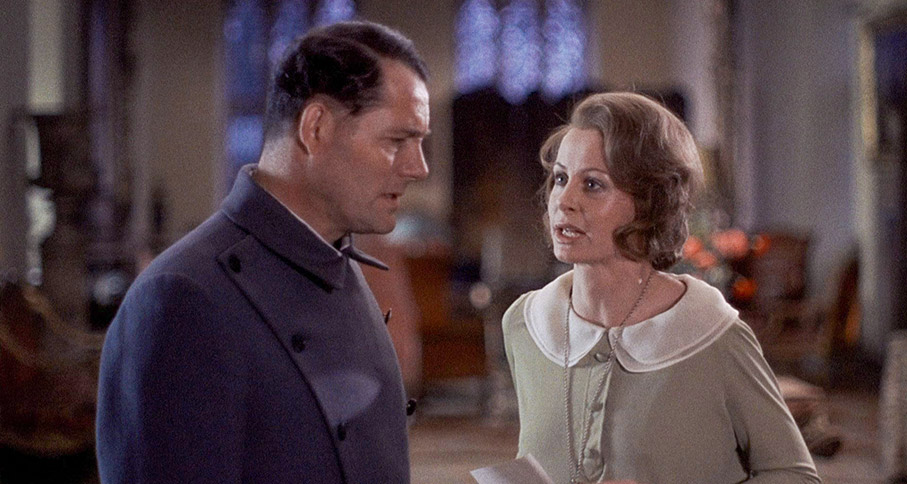

Helen seems a little more focussed, if no less emotionally hollowed out, when talking to Doctor Mercer, who writes as he speaks but only looks Helen in the eye when she prematurely stands up to leave. It's a move that the doctor instinctively counters by starting to stand himself, only to halt his action midway and ease back down into his chair, which has the effect of prompting Helen to do likewise. As the two uncomfortably converse, key information is casually mentioned or implied, that Helen had a nervous breakdown after the death of her husband, and that she subsequently did something unspecified that led to her being either admitted or committed to this sanitorium. Mercer continues to avoid looking directly at Helen, and when she attempts to discuss the incident that landed her here by stating that her actions were deliberate, he brushes it aside in a manner that suggests he finds the subject either too tiresome or too distasteful to discuss. "I still feel it a little bit in the mornings," Helen tells him, subtly hinting at the nature of the event in question, which the doctor bats away by telling her, "You need people now," whilst focussing his attention on an object on his desk that he is distractedly playing with. Not for the first time during this meeting, Helen finds herself staring at the doctor's glasses, which are laid on the desk directly in front of his busy hand. "I don't know many people," she tells him, but when she tries to explain that things were different when she and her late husband were in London, the doctor once again deflects. When the nurse pops her head in to offer Mercer an escape route, Helen turns her head in her direction just enough to reveal that a tear has run most of the way down her right cheek. In the space of just three minutes of unhurried screen time, we learn a surprising amount about her ladyship, despite little being explicitly stated.

Helen's aristocratic status is confirmed when she is met at the hospital entrance by a vintage Rolls Royce car driven by a uniformed chauffeur named Steven (Robert Shaw), who dutifully holds the rear door open for her to enter. Only when the car gets underway is it revealed that Steven is not the family driver but an employee of a large car hire company who has been tasked with collecting her. Helen presumes it was arranged by her mother, to whose home they are currently heading. In the course of their journey, a casual enquiry about an open car window initiates a tentative conversation between the two, which at one point briefly puts a surprised smile on Helen's face. Despite this, Steven adopts a businesslike tone throughout and always refers to Helen as 'milady', and when they arrive at Helen's mother's upmarket Lansdowne Crescent house, Helen thanks him for a very pleasant drive and the two part company.

What follows reveals more about both characters. A clearly uncomfortable Helen has tea with her even posher mother (Elizabeth Sellars), where the two dance nervously around the whole issue of Helen's breakdown, and nearly have a row when the mother seconds Doctor Mercer's words and insists that she try to make some friends. When Helen breaks into uncontrolled sobs of guilt for being out partying when her husband needed her the most, instead of comforting her as expected, her mother walks over to the window to keep an eye on the window cleaner working outside, seemingly more concerned about how this might look to others than her daughter's distress.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the social scale, we discover that far from being an employee of a large firm as he claimed, Steven lives in a dour one-room flat above a small garage from which he runs a small but aspiring car hire company with a mechanic named Davis (Ian Hogg). Once again, the relationship between the two men is quickly defined by their interaction, with David sarcastically muttering "yes, sergeant major" as Steven barks out orders like the two are back in the First World War trenches where we can presume they first met. This is not the only tall tale that Steven spins to Helen, responding as he does to her enquiries about whether he has a family with the claim that he has a wife and two sons, when in fact he is single and conducting a cheerless on-off affair with a local barmaid.

It should come as no surprise that Helen re-employs Steven as a driver or that they become closer the more time they spend together, but it's a relationship that moves forward in sometimes awkward fits and starts. When Helen asks if she can sit up front with Steven because it's something that she's always wanted to do, for instance, he agrees but is clearly made uncomfortable by this break to the accepted protocol, which is then re-established when he drives her to visit her plush country house for the first time since her breakdown and ends up dining in the kitchen with the domestic staff.

Later in the story, Steven is also discomforted when a by-then more confident Helen offers to give him the money he needs to pay off a loan on the car with which he makes his living, only reluctantly accepting when her persistence makes it difficult for him to continue to refuse. The thing is, by this point it's hard to be sure whether he's speaking from the heart or putting up a fake show of resistance in the knowledge that he'll get the money he needs. By now, Steven has a grown immensely fond of Helen, yet despite her warmth towards him and the positive effect their friendship has had on her recovery and self-confidence, he is blind to the possibility that his feelings might not be reciprocated in kind, and is thus sent into a jealous sulk when Helen is wooed by Captain Hugh Cantrip (Peter Egan), an aspiring political candidate and Steven's former commanding officer. His mood is worsened when the first job for Helen after two weeks of silence is not to drive her but to collect some shopping and deliver it to the house, a call made by Helen's housekeeper that Steven refuses to take and that ultimately has to be answered by Davis. When Steven arrives at the house and approaches the busily distracted Helen, his intimation that he might soon have to sell the business and move away certainly plays like a ploy to trigger sympathy with the aim of reigniting her interest in him. But when she insists on financially assisting him, his reluctance to accept her offer feels initially real, as if he hadn't expected the story he has told (which includes the claim that he has medical expenses for his non-existent wife) to trigger this response. This expressed resistance does falter when Helen grabs her cheque book and insists that he tells her how much he owes, but when she hands him the cheque, he once again tells her that he cannot accept it, seriously discomforted by this breakdown of the accepted social order and the impact this charitable move – one that Helen can easily afford – has on his entrepreneurial pride.

That The Hireling is as much a critique of the British class system as it is a character drama is signalled at an early stage, as the wealthy but fragile Helen is driven from a doubtless exclusive sanitorium in an expensive car by a uniformed member of the working class to a house that only someone of her social status could ever afford. On the way, they repeatedly pass individuals that Helen's mother would doubtless describe as peasants, the local land-working poor and their children, who dispassionately observe this opulent symbol of wealth and privilege as it passes. Traditional class protocols are initially observed, with Steven showing the expected deference to Helen, who is only ever referred to by that name by others of her social status and always as either Lady Franklin or "milady" by Steven and the domestic staff who serve her. Even at their closest, Steven never calls her by her first name, and Helen only discovers that the man she has befriended and spent so much positive time with is named Steven when she has to write his full name on the aforementioned cheque.

Despite coming from opposite ends of a class system that held even more sway in the period in which the film is set, the more time Helen and Steven spend together, the more the sense that traditional social barriers are starting to crumble (spoilers ahead – skip to the next paragraph to avoid). But ultimately this all proves to be an illusion, one that Steven is seduced by but that Helen embraces only while it helps her to regain her former self-confidence. And despite a candlelit Lady Chatterley moment when Steven rolls up his sleeves to fix a basement generator and Helen's eyes are drawn to the tattoo on his muscular arm, when Steven's growing fondness spills over into openly expressed desire, Helen is genuinely startled and strongly resistant to his clumsily forceful attempt to seduce her. For Steven, the stark difference in their backgrounds and social status should not be a barrier to a relationship that would be a step too far for Helen, hence her rejection of his overtures in favour of a romance with the self-satisfied but upper-crust Cantrip. While the film does suggest that social barriers can be lowered to facilitate a degree of friendship, it ultimately concludes that a class-based society will ultimately insist that everyone should know their place and not fraternise with those that are considered by their peers to be socially either above or beneath them. It's a turn of events that completely reverses the fortunes of the leads, with Helen regaining her former strength as Steven suffers an emotional breakdown.

This Blu-ray of The Hireling was released by Indicator on the same day as Peter Yates' The Dresser (1983), and whether this was a calculated decision is not something I am in a position to confirm, but if not, the coincidences are interesting. Both films are built around a pair of characters of differing social status within their respective worlds, one of whom is tasked with serving the other, which they do as much out of devotion to the individual as to duty, and both feature impeccable performances from their sublimely cast leads. Robert Shaw is at his restrained best here as the ambitious but dutiful Steven, commandingly bossy when addressing Davis, and managing the swings between friendliness, sulking jealousy and frustrated anger without ever overplaying a note. When he does lose his rag in the later stages, the sense of potentially explosive, pent-up fury that he is able to radiate is genuinely startling. He's matched all the way by Sarah Miles, who perfectly captures Helen's gradual metamorphosis from frightened fragility to self-confident lady of the manor, particularly the small baby steps she takes in Steven's company in the first half of the story. In a strong supporting cast, Peter Egan is appropriately oily as Captain Cantrip, Elizabeth Sellars radiates smug social superiority as Helen's mother, and Ian Hogg is engagingly long-suffering and quietly sarcastic as Davis. I also liked Petra Markham's brief role as Helen's young housemaid Edith, whose respect for her employers only goes so far and who is able to suggest her attraction to Steven with no more than a quickly flashed glance.

The Hireling was based on a novel by L.P. Hartley, which I confess to never having read, and despite the high regard in which the film is generally held, I have seen a couple of reviews expressing disappointment at the changes made to it by respected screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz (he of Expresso Bongo, The Day the Earth Caught Fire, The Assassination Bureau, and more). I'm not in a position to comment on that, but as a stand-alone film work, The Hireling is a compellingly told and impeccably acted drama, unobtrusively but intelligently handled by director Alan Bridges, who worked primarily in television and won a BAFTA for an episode of the prestigious drama series Play for Today titled The Lie (1970), an English language adaptation of a Swedish television play by Ingmar Bergman. The Hireling itself was a triple BAFTA winner, for Natasha Kroll's art direction, Phyllis Dalton's costume design, and for Peter Egan in the Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles category, even though he plays a supporting role here. Even more significant, the film won the prestigious Grand Prix at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, a prize it shared with Jerry Schatzberg's The Scarecrow, another film built around two characters and two excellent central performances, this time from Al Pacino and Gene Hackman. Like The Hireling, it's a film that attracted much praise on its release but is rarely seen or discussed half a decade later. One for a future Indicator release, perhaps?

All I know about the 1080p presentation on Indicator's Blu-ray is that it is sourced from a Sony HD remaster and based on the quality of the resulting transfer I have to believe that process involved a degree of restoration, as the picture is virtually spotless and in consistently impressive shape. Framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the transfer handsomely showcases Michael Reed's carefully crafted cinematography and lighting, which despite presenting England almost expressionistically as a place where the sun rarely ever seems to shine, the image never feels remotely flat or dour. Detail is sharply defined, the colour is pleasingly naturalistic, and the contrast is very nicely balanced, with rock-solid black levels when required but clear shadow detail elsewhere.

The mono soundtrack is presented as a Linear PCM 1.0 track, and it's also in good shape, with clear reproduction of dialogue, ambient effects and music, and no obvious traces of damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

The Driving Force (11:13)

A featurette in which a few of the surviving cast and crew of The Hireling look back at the making of the film. Actor Sarah Miles praises L.P. Hartley's original novel and director Alan Bridges, wardrobe mistress Brenda Dabbs admits that it's sad film but it didn't seem that way when they were making it, and production manager Hugh Harlow recalls filming at Sutton Place, the home of famed billionaire J. Paul Getty, who despite his immense wealth had a payphone installed for his staff to use should they need to make a call. Production accountant Maureen Newman outlines some of the specifics of her job and describes producer Ben Arbeid as tremendously well organised, actor Ian Hogg remembers driving to and from the location on his motorbike and also has positive things to say about director Bridges, and composer Marc Wilkinson briefly outlines how he designed the music to reflect the personalities of characters. It's all interesting but briefer than expected, as almost half of the running time is made up of clips from the film, which are used to pad out and separate the interview clips.

The Lady and the Chauffeur (11:10)

More of the above, although this time the focus is the two lead actors, with particular emphasis on Robert Shaw. Hugh Harlow praises Shaw and his work and was particularly impressed that he would head to the local pub at the end of shooting each day to play darts. He also provides some interesting background information on a late scene involving a car that I can't be specific about without getting into spoiler territory. Brenda Dabbs recalls the challenge of having to arrange a last minute costume change when the walls at the location turned out to be the same colour as Sarah Miles' dress, and Miles herself remembers getting competitive with Shaw when they both received scripts for Hollywood films on the same day, and losing out to Shaw when his film, The Sting (1973), turned out to be one of the biggest hits of the decade.

BEHP Interview with Phyllis Dalton (105:02)

Running as a second audio track for the film, this recording of the British Entertainment History Project interview with costume designer Phyllis Dalton was one I'd somehow convinced myself would be of only minor interest to me, and I salute Dalton for proving me soundly wrong. Not only did she have a career that spanned decades of sometimes remarkable films, she quickly made me realise how little I knew about the challenges that a costume designer faces on any film, let alone ones of the scale that Dalton was sometimes employed on. After outlining how her early interest in clothing design and a stint at art school led her into costumery and eventually the movie business, she takes us on a trip through just about every film that she subsequently worked on. Many of these are covered in just one or two sentences (The Hireling prompts her only to note that she won a BAFTA for her work on it), a couple are curtly dismissed (she describes 1956 Zarak as "a rock-bottom disaster"), while a small number are covered in much more detail at the prompting of the unnamed interviewer. These include Dalton's work for David Lean on Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, for Carol Reed (whom she describes as a much nicer person than David Lean) on Our Man in Havana and Oliver!, and for Kenneth Branagh on Henry V, a film that she amusingly refers to as "Henry Five." She also designed the costumes for Rob Reiner's cult favourite The Princess Bride, a film our erstwhile interviewer has to ask her to describe because he's never heard of it.

Theatrical Trailer (3:02)

A functional but spoiler-heavy trailer that plays on the film's Cannes win but leans into the later scenes when the relationship between Helen and Steven has complicated, and it isn't shy about showing why. Leave this one until after seeing the film.

Larry Karaszewski trailer commentary (3:35)

Screenwriter and Trailers From Hell regular Larry Karaszewski notes the film's win at Cannes and wonders why it has left such a small footprint on film history, as well as praising the plot and the performances and talking briefly about director Alan Bridges.

Image gallery

28 screens of production stills – including a couple of behind-the-scenes photos – and international poster artwork.

Booklet

The lead essay in this 32-page booklet is by respected film writer Peter Cowie and opens with the pertinent suggestion that the film is one of the harbingers of what he neatly describes as 'country house' cinema, before taking a detailed look at its makers, particularly lead actors Robert Shaw and Sarah Miles and director Alan Bridges. There are some nice observations here, my favourite being the idea that actor Peter Egan, who plays Captain Cantrip, has a voice that "evokes the sound of a falling £50 note." What I wouldn't give to have come up with that line. Next is a piece that alternates between information about screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz and extracts from interviews with the man himself in which he reflects on the process of adapting L.P. Hartley's novel for the screen. He also explains the changes he made to the original, some of which are handily outlined here. Finally, we have extracts from a range of positive reviews from the British and American press. Full credits for the film are included, and the booklet is, as ever, attractively presented and illustrated.

An unfairly neglected social drama built around two characters at opposite ends of the British class system whose growing relationship appears to be dissolving social barriers, only for the know your place-ness of the day (which still exists and frankly needs to be torn asunder) to rear its prejudicial head. A smart script by old hand Wolf Mankowitz, subtle but effectively on-point direction from Alan Bridges, mood-setting cinematography by Michael Reed, and a slyly discomforting score by Marc Wilkinson, and close to career best performances from the two leads make The Hireling consistently compelling viewing. Another solid transfer and a modest selection of decently targeted special features make this an easy disc to recommend.

|