| |

'My daughter Chigumi was thirteen years old at the time and she was absolutely mad about cinema. She'd just got out of the bath and was doing her make-up, brushing her long hair that she was so proud of in front of a mirror. I said to Chigumi, "They're looking for a treatment for an exciting film like Jaws. What do you think?" I asked her. She said, "If my reflection in the mirror could jump out and eat me, that'd be scary."' |

| |

Director Ôbayashi Nobuhiko on the genesis of Hausu |

As a title, House was some time ago hijacked by the televisual branch of the medical profession, with its MD suffix and its reference to the dying tradition of doctor's house calls. Long term horror fans, however, will recall it as a witty genre work from 1986, one written by Monster Squad's Fred Dekker and directed by Warlock's Steve Miner. It even gave birth to a short-lived franchise. But previous to this, the title was owned by a 1977 Japanese film directed by Ôbayashi Nobuhiko, one that certainly qualifies as a horror film but which falls into so many other categories, including a few of its own invention, that actually classifying it in genre terms is a near impossible task.

It's hard to resist trotting out a critical cliché here and suggesting that you've never seen a film quite like House (or Hausu, the Japanese spelling of its very English title). Yet here it’s justified, as even if your viewing habits are varied and your relationship with eclectic and even experimental cinema is long-standing, I'm still willing to bet you've never witnessed anything quite like this. And unless you've spent a weekend in a haunted house with a bunch of lively Japanese schoolgirls after overdosing on teen comics and cinematic postmodernism and swallowing a Fear and Loathing-sized cocktail of hallucinogenic drugs, I'm not sure you'll be able to imagine it either. You'll see drugs mentioned a lot in relation to the experience of watching this movie, and with good reason. One IMDb contributor even suggested that watching it after taking drugs might actually kill you. He may have a point. So how the hell do I go about describing it?

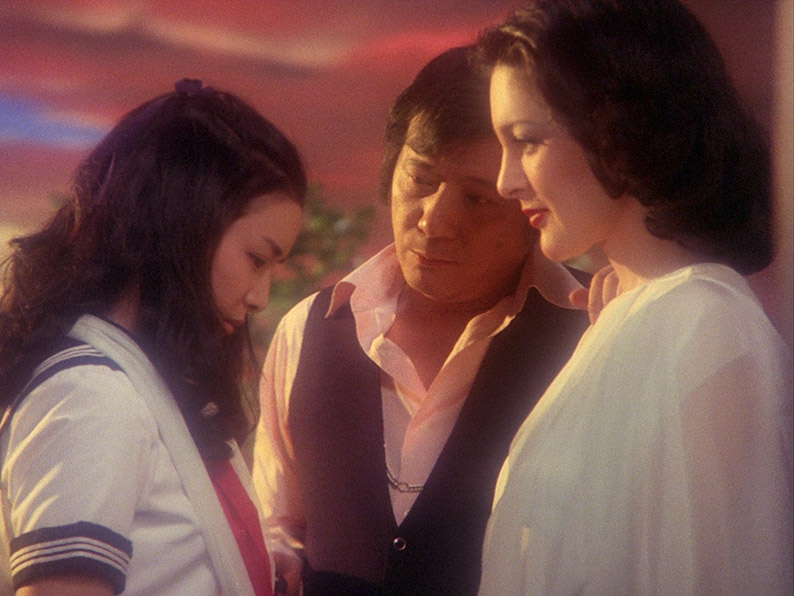

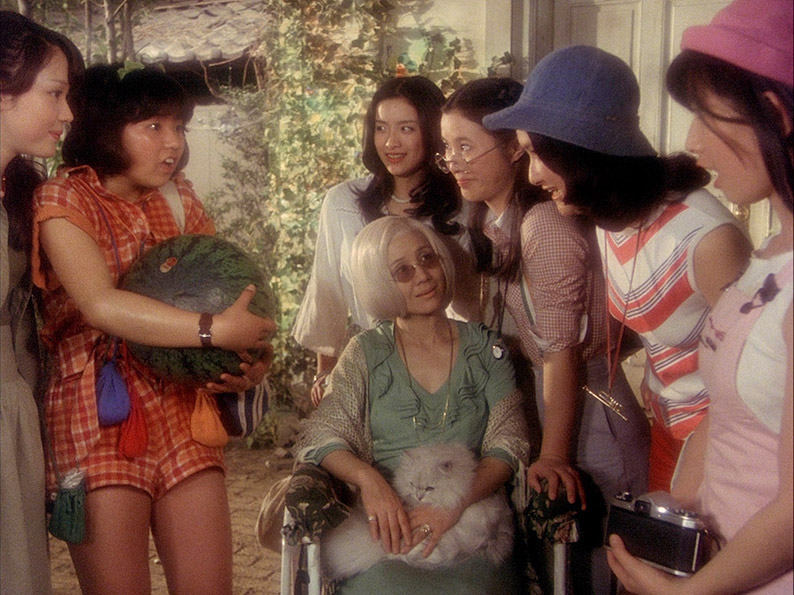

Nothing is straightforward or plays by any sort of rule book here, and I do mean nothing. This includes our principal characters, an effervescent group of Japanese schoolgirls with English nicknames that reflect their most prominent character traits. There's musical Melody, kick-boxing Kung-Fu, daydreaming Fantasy, studious Prof, loveable Sweetie, and ever-hungry Mac (short for 'stomach' apparently), all of whom are due to head off to summer camp with dishy male teacher Mr. Togo. Unable to join them is their good friend Angel, who instead is looking forward to spending the summer with her widowed film composer father at his villa. But dad has a surprise for his devoted daughter, that they're to be joined on their trip by his new girlfriend Ryoko, a glamorous creature whose neck scarf is kept fluttering by a special breeze that seems to follow her around for this very purpose, even indoors. An immensely unhappy Angel decides instead to head out to the countryside to visit an auntie she's not seen since she was an infant, and when the camping trip that her friends were so looking forward to unexpectedly falls through, Angel invites them to join her instead.

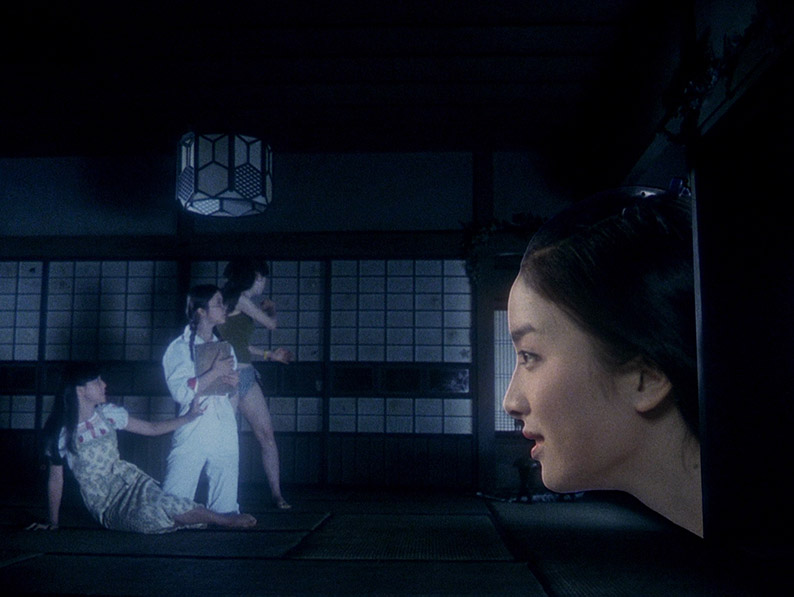

Don't be fooled by the deceptive straightforwardness of the above plot summary, as we've not got to the wild stuff yet, not by a long shot. Already, however, we've been treated to the following: a tongue-in-cheek animated title sequence; a sugary-sweet parting of friends that plays almost like a Hello Kitty take on lesbian love; a balcony whose background is as stylised as the bridge set from William Cameron Menzies’ Invaders From Mars; a cobbler and his daughter, who bob to the score like background characters in a musical; a stop-motion downstairs tumble that wedges Mr. Togo's behind in a metal dish that a child then proceeds to play like a drum; a train journey presented in the style of a picture book for children; the romantic soft-edged circular framing of faces; oddball camera angles; freeze-frames; split screen; heavily colour-tinted imagery; and a family history realised as silent movie footage – complete with visible film sprockets, captions, jitter and frame burn – that the girls all comment on as if they're watching it in a cinema. And believe me, you ain't seen nothin' yet.

As the girls settle in and Angel's welcoming, wheelchair-bound Auntie licks her lips at the sight of Mac's tasty plumpness, things gradually evolve from strange to completely bonkers. Mac disappears, and her head turns up in a well in the garden, then darts through the air like a possessed mosquito and bites Fantasy on the behind, which sends her screaming indoors where her friends dismiss this as another one of her daydreams. She's further spooked when the newly invigorated Auntie disappears into the fridge, only to reappear seconds later just feet from the camera and smile knowingly at the audience, then drift into a contented dance to a recurring tune that's accompanied here by musical cat meows.

The madness builds to a mountain-range of peaks as the girls are individually possessed and ingested by whatever has been lying waiting in the house for their arrival. One is transformed into fire; another is wedged into the mechanism of a clock; and in a thermonuclear explosion of audio-visual insanity that includes animated overlays, flying limbs, a dancing skeleton, dizzying camera moves, eye-popping process work and hand-drawn frame borders, a third is attacked and eaten by a piano. The potential for Mr. Togo to fulfil the role of knight in shining armour of Fantasy's cinematic daydream, meanwhile, is frustrated by city traffic and a bizarre botanic transformation resulting from his preference for bananas over watermelons. By the climax, you'd be forgiven for thinking there was nowhere left for the film to go, but it goes there anyway, as partial explanations are delivered by a pair of giant floating lips, body parts float in a kaleidoscopic dance, and the surviving girls are assaulted by flying furniture, a martial arts geisha and a river of blood, a sequence that's shot and edited like a hyperactive acid trip.

But while it may repeatedly seem as if first-time feature director Ôbayashi has taken leave of his senses, the care taken with which each inventively composed shot, colourfully artificial background and pre-digital effect makes it clear he knows exactly what he's doing. This stylised artificiality has its direct descendent in the cinema of Kamikaze Girls and Memories of Matsuko director Nakashima Tetsuya, but while the technique of Nakashima's films sometimes calls attention to itself at the expense of character and story (at least for this still undecided viewer), the technical wildness of House feels organically melded to both, a subjective approach that portrays events as they are perceived by characters who are too frightened, confused and emotionally involved to experience in a remotely objective manner. The result is a bizarre and brilliant mindfuck of a film, one whose energy, unbridled visual and aural creativity and manic sense of fun really do put it in a class of its own.

When House was released on DVD by Masters of Cinema back in 2009, the 1.55:1 transfer was solid but a little shy of great. The image was never pin-sharp and the contrast aggressive, resulting in dark scenes and shadows that really sucked in detail. Blu-ray upgrades of existing titles by the same distributor sometimes sport an HD transfer from the very same master, so the improvements are restricted to the sharpness only, but that’s definitely not the case here. Up front, we’re informed that this transfer has been licenced from Janus Films and the Criterion Collection, and there are very visible improvements across the board. As you would expect, the image is definitely sharper, and while some sequences still have a slightly soft-focus look, this is clearly intentional (parodic friendship and romance shots, for example), and elsewhere the picture is noticeably crisper and the detail more distinct. But there’s more. The contrast is far more generously balanced than it was on the DVD release and exposes far more detail in shadows and darker scenes without greying out the legitimate black levels, as well as eliminating occasional burned-out highlights. The colour has also been toned down a notch, and when compared side-by-side with the DVD, the earlier release now looks a little over-saturated – colours are still vividly rendered here, but do not explode quite so violently from the screen. In addition, the colour balance on the Blu-ray actually differs from that of the DVD in places, and I’m not in a position to say with any authority which is correct. It's the same story with the framing, which has been opened out at the top and bottom here to 1.33:1. In addition, the dust spots present on the DVD transfer appear to have all been cleaned up. The film really does look terrific here.

|

| Compare this grab from the Blu-ray (above) with the previous DVD (below) |

|

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track is in solid shape, and in terms of dialogue, effects and music clarity, has a small but audible edge over the Dolby 2.0 mono track on the DVD. No damage or distracting background hiss was detectable.

The English subtitles are optional, and as you would expect are crisper and clearer than their DVD forebears.

Most of the extra features have been carried over from the previous DVD release and comprise of eight interviews with some of the project's key personnel. It’s worth noting that they are all standard definition blown up to HD and that their collective length excedes that of the main feature.

In Beginnings (17:04), director Ôbayashi Nobuhiko relates, in the soft-spoken but enthralling manner of a kindly Jackanory storyteller, the events that led up to his writing a proposal for a film that would be "even more exciting than Jaws," an international blockbuster whose runaway success Japanese studios were keen to emulate. His own background in experimental films (particularly his acclaimed 1966 short Emotion) and TV commercials is covered in detail, and some very useful cultural context is provided. There’s some intriguing stuff here, with Ôbayashi describing commercial cinema as "independent films with sponsors" and listing the big stars he was excited to work with in Hollywood, which include Kirk Douglas, Sophia Loren, Catherine Deneuve and, erm, Ringo Starr.

The story is continued in Pitch (7:34), where Ôbayashi explains how the film was first conceived (the quote at the top of the review will give you an idea) and how he came to direct it for Toho after none of the regular studio directors would touch it because it was deemed "too silly."

In Script (15:24), Ôbayashi and his daughter Chigumi look back at the genesis of the script and expand on Chigumi's contribution – she was even given a credit as story originator and treated like a VIP when she visited the set. Some interesting anecdotes about the production are recalled – one involving broken sunglasses and the lighting crew is rather nice – and Ôbayashi reveals much about his approach to the film when he says that "I want the cinema to be fun and full of dreams," and that it could not have been made by adults alone and "needed a child's sensibility."

Ôbayashi is back on his own for Pre-Release (15:37), where he outlines the specifics of the then revolutionary multi-media promotional campaign he devised – which included business cards and stickers based on the poster (created by animator Shimamura Tatso based on Ôbayashi's design), newspaper stories, interviews, a manga comic, a soundtrack record and even a radio play – to push the film even before Toho had agreed to make it.

In Publicity (3:33), Tomiyama Shogo, the man put in charge of publicising the film's original release and now a successful producer in his own right, concisely outlines how House was originally promoted, particularly the use of Ôbayashi's poster design as a corporate image and the multi-media approach.

In Casting & Production (20:22), Ôbayashi looks back with some affection at the process of casting relatively inexperienced young actors, at the atmosphere on set and his efforts to break down divisions of labour, at how the new smaller Panavision cameras changed the way films were made, and how the pre-publicity sparked the interest of younger audiences who had lost interest in traditional Japanese cinema. Toho Studio representative Matsuoka Isao apparently told Ôbayashi "I've never seen such an incomprehensible script," and meant it as a compliment, while sound advice was provided by the then editor-in-chief of Japan's primo cinema magazine, Kinema Junpo, when he told the director: "Plenty of people can make ordinary films better than you. So make something that nobody else would."

In Fantasy (2:13), actress Oba Kumiko – who plays Fantasy in the film – briefly recalls her work on the production, particularly a climax that involved being repeatedly soaked and having furniture thrown at her.

Finally, in Release & Legacy (7:29), Ôbayashi muses on the legacy of the film, how it opened a door for other industry outsiders to direct studio productions, and how it ushered in an era of new young filmmakers like Kurosawa Kiyoshi, the acclaimed director of Cure, Creepy and Tokyo Sonata.

Video Essay by David Cairns (26:50)

New and exclusive to Eureka’s Blu-ray, this video essay is comprised of extracts from the film, under which Cairns outlines how Ôbayashi first fell in love with the movies and provides an overview of his early experimental work. He reveals that Ôbayashi directed over 2,000 commercials before embarking on House, which he then examines from a number of interesting angles. I was amused to learn that the film was first promoted as "The cutest nightmare you ever had."

The original Trailer (1:35) gives a flavour of the film's creative madness, and the film itself is just too out there for anything here to count as a spoiler.

Also included is a typically well-produced Booklet, the meat of which is a detailed and enthralling essay by Paul Roquet on director Ôbayashi and the film itself. Credits, poster reproductions and plenty of promotional stills have also been included.

Back in 2009, when Eureka first released House on DVD, I approached it with an open mind and little knowledge of what I was about to be hit with, and emerged from the experience with the sense that my brain had been put into a blender and then laced with an elephantine collection of hallucinogens. Nine years later, I’ve yet to see anything quite like it and thus still has the potential to blow the mind of an unwary viewer. I still can’t believe those who put up the money for what they hoped would be a film that would compete with Jaws green-lighted the project and let Ôbayashi get away with what he does here, and my jaw still drops at the sheer invention and imagination that has gone into almost every shot in the film. Wild, weird and wonderful, House is the sort of first film that young aspiring auteurs everywhere (Ôbayashi, it should be noted, was close to forty when he made it) must dream of delivering, one that breaks all the rules, opens doors for other independent filmmakers, and is a big hit with its target audience.

If you already have the Masters of Cinema DVD then you’ll also have most of the special features included here, but I'm still glad to see them included and the David Cairns video essay is an informative addition. The real selling point here, however, is the considerable jump in picture quality, which easily eclipses that of its DVD predecessor on just about every score. A most worthy upgrade, and if you don't already own the DVD then this is an absolute must-have. Highly recommended.

This review is an updated version of our earlier DVD review of House.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.

|