|

When it comes to horror, particularly horror from years past, there are certain things that can usually be relied on. Here's three off the top of my head: isolated houses will harbour dark secrets; scientific experiments on humans or animals are generally destined to end in disaster; and black cats tend to be either sinister in themselves or harbingers of approaching doom. One such trope that I’d almost forgotten about but have been given cause to recall of late is that once a man (it’s always a man) is convicted of murder, every cell in his body has the potential to infect and ultimately control the mind and body of another. Thus, if his eyes are transplanted into the head of a blind man to restore his sight, the recipient will see the world through the eyes of the killer. Transplant his brain into the body of a creature created from various corpses and you’re really asking for trouble, as a certain Victor Frankenstein learned to his cost. Even a murderer’s blood has the potential to turn its new host into a crazed killer, at least if the 1940 Boris Karloff vehicle Before I Hang (one of six films included in Eureka’s recent Karloff at Columbia box set) is anything to go by. Leading the way in this fruitful subgenre was the Austrian silent feature, The Hands of Orlac [Orlac’s Hände], which was directed way back in 1924 by The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’s Robert Wiene and starred that film’s second lead, Conrad Veidt. An adaptation of the novel 1920 novel Les Mains d'Orlac by Maurice Renard, the film may be one of the pioneers of this particular horror trope, but for those coming to it retrospectively after years of variations on the same theme, The Hands of Orlac has a couple of rather neat surprises up its sleeve, albeit ones I cannot discuss without dishing out a spoiler warning or two in advance.

Veidt plays concert pianist Paul Orlac, who when travelling home after his latest tour is seriously injured in a head-on train crash. The base of his skull is fractured, but the hands that are his livelihood are damaged beyond useful repair. When Paul’s devoted wife Yvonne (Alexandra Sorina) begs surgeon Dr. Serra (Hans Homma) to save them, the good doctor does so by replacing Paul’s now useless hands with those of newly executed murderer Vasseur. On discovering this, Paul’s becomes convinced that his new hands are inherently evil and that he has somehow been transformed by their attachment to him. His handwriting has changed, he is no longer able to play the piano, and he declares that he will never again hold anyone with them, the distraught Yvonne included.

Normally, I would continue outlining how this concept is developed into a story, but the event that really triggers this occurs far later in the film than a more complete plot summary might lead you expect. So would revealing it count as a spoiler? Well, yes, maybe, so if you want to go into the film cold, I’d skip this the following paragraph (or simply click here). There will be a more emphatic spoiler warning (and another bypass link) later, when I get into how the film ends and what so wound me up about one aspect of it.

Things really complicate for Paul when his inability to play effectively shuts down his only source of income. His father (Fritz Strassny) is a wealthy but spectacularly miserable man who for reasons not explained in the film has absolutely no time for his son, and when Yvonne pays him a visit to beg for his financial assistance, his sole response is to express his continuing hatred for his offspring. With creditors now knocking on their door, Yvonne persuades Paul to pay his father a call, but when enters his house he finds him dead with a knife plunged into his body, one whose distinctive design is identified by the police as the weapon used by Vasseur to kill his victim. Making matters worse, Vasseur’s fingerprints are also discovered on the weapon and elsewhere at the crime scene (full marks to the detective who can recognise them on sight), and when Orlac Senior’s devoted and deeply shocked manservant (Paul Askonas) appears, he reveals that he was lured away by a note falsely claiming that his sister was at death’s door, one written in the dead Vasseur’s handwriting. The police are confused, but as we and the now terrified Paul are well aware, Vasseur may be dead but his hands are still very much alive. Could Paul’s fears about having the hands of a convicted murderer be justified after all?

The Hands of Orlac is a film that some genre writers have labelled a minor classic but that others regard as an interesting film rather than a great one, and I have to admit that I can see where they are coming from. Being the work of director Robert Wiene, it inevitably gets unfavourably compared to The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, a landmark film that cast a sizeable expressionist shadow over a genre that at this point was still in the process of taking shape. Expressionism certainly plays a role here, but its use is more limited and a little sporadic, giving a stylistic edge to certain scenes and underscoring the emotional state of the lead characters. The Hands of Orlac is a less experimental and less artistically adventurous work than its remarkable forebear, one focussed almost solely on its characters and, to a lesser degree, its story, and it’s here that some of the disagreement about the film’s qualities lie.

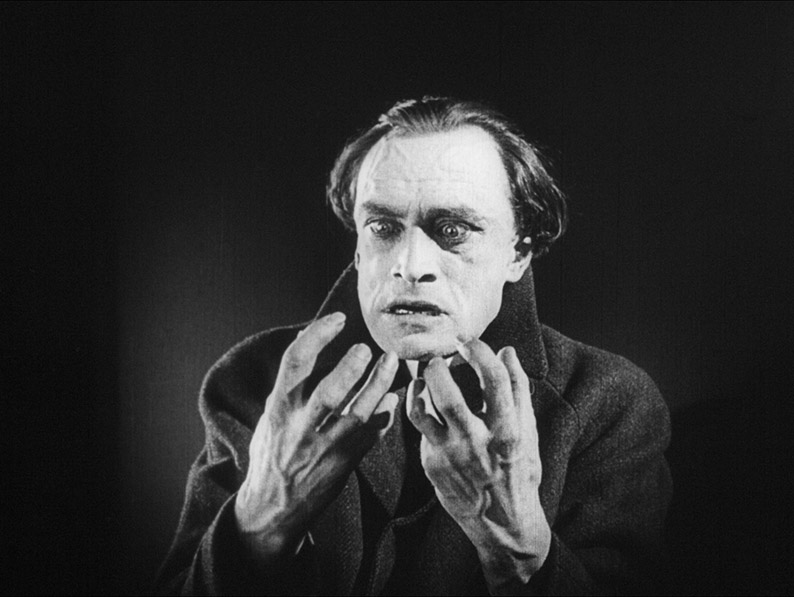

More than once in past reviews I’ve suggested that we often approach silent cinema with certain preconceptions about how it will be performed, usually to set the scene for one that usurps these expectations by displaying an unexpected level of subtlety (try the marvellous Emil Jannings in F.W. Murnau’s glorious Der letzte Mann). The Hands of Orlac is not such a work. So brilliant in the title role in Paul Leni’s 1928 The Man Who Laughs, Conrad Veidt here sometimes plays Paul to the very rear of the gallery and a little bit beyond – when Paul is fearful that his new hands may be possessed by the spirit of their former owner, his eyes bulge, his mouth widens in a horrified grimmace and he stares at his outstretched limbs like a man who has taken a heroic dose of PCP and is hallucinating an image of them covered in monstrous and flesh-devouring insects. Equally (over-) expressive is Russian actor Alexandra Sorina as Yvonne, whose emotions are sometimes so exaggerated that her distress and anxiety occasionally take on an almost orgasmic quality. This air of sexuality certainly underscores the sequence in which she comforts the newly revived Paul, and is even more blatant in a later scene, when what appears to be the ghost of Vasseur commands housemaid Regine (Carmen Cartellieri) to approach Paul and “seduce his hands.” The frightened but intimidated Regine then does as ordered by allowing Paul to caress her head, an action that appears to bring both to the brink of ecstasy, at least until Regine is freaked out by the notion of being fondled by a murderer’s hands.

Yet somehow this all works for a film whose most expressionistic element, despite Stefan Wessely’s captivating art direction and the shadows and light of Hans Androschin and Günther Krampf’s cinematography, lies in lead characters whose interior emotions are fully externalised – there’s a very real sense that their performances are designed not to show how Paul and Yvonne would behave in real life, but to function as a physical and emotional representation of their inner torment. This extends to Paul’s father, who appears to spend all of his waking hours sitting morosely in a chair in an archway in the corner a large and sparsely furnished room, an unlikely scenario in the real world that is nonetheless effective as an expression of the man’s loneliness and inexplicable but deeply felt bitterness towards his son. That said, I did like Carmen Cartellieri’s more naturalistic turn as Regine, but stealing the film in just a handful of sequences is Fritz Kortner as the man who may or may not be Vasseur’s ghost, from his first creepy appearance as a face peering through the window of a hospital door to his smarmily self-confident later dealings with the terrified Paul.

For its place in film history and its later influence, The Hands of Orlac is an undeniably fascinating work, being a launchpad for both the ‘evil transplanted limbs and organs’ and body horror subgenres and the first adaptation of a novel that has since been remade five times under various guises. Original author Maurice Renard may have been the one with the foresight to incorporate a medical procedure that in the real world wouldn’t be successfully performed until the very end of the twentieth century, but the film presents it in a credible and pleasingly non-fantastical manner. Sure, The Hands of Orlac is nowhere near as artistically adventurous, as iconic or as dramatically compelling as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and there are sequences in which the pacing feels almost deliberately slowed to pad out the slimmer aspects of the story. But there’s something about it that kept pulling me back to re-examine scenes that I initially found a little plodding and read them in a different and more subtextually significant light. And despite the slow pace of much of the film’s midsection, it’s bookends are really something, opening as it does with a strikingly realised post-train crash sequence and concluding with a series of revelations that neatly tie up the main story and do not insult the intelligence. There’s just a couple of things here that bother me, and…

Okay, here’s where I ideally should just keep things vague and express my frustration and uncertainty in abstract terms, but I really do feel the need to expand on this one, and as this means revealing how the film ends, I really would encourage anyone who hasn’t seen it and intends to do so to skip to the Sound and Vision section and give the rest of the film review a miss, at least until after you’ve watched the film. Seriously, spoilers don’t get much bigger than this. You can click here to automatically bypass the next paragraph.

As those familiar with the film will know, at the climax of the film, the man Paul believed was Vasseur’s ghost is revealed to be a crook named Nera, a man whose frankly rather ingenious plan to con Paul out of money he no longer has is exposed and detailed in the final scene. It’s here that Paul learns that Nera not only killed his father but also committed the murder for which Vasseur was convicted and executed, and given the trouble Nera went to in order to trick Paul, I was left in no doubt that he was able to manufacture a cast-iron case against the unfortunate Vasseur. When all this is revealed and Paul learns that he doesn’t have the hands of a murderer after all, he is genuinely overjoyed, and this is the basis for what, on the surface, is a happy ending. Oh really? Do you think so? What about Vasseur? This man was wrongly accused of murder, convicted on false evidence and executed by having his head cleaved off with a guillotine, but within the narrative of the film that’s fine, because it means Paul has the hands of an innocent man instead of a killer. On my first viewing, this had me genuinely yelling at the screen in disbelief. But there’s more. Given that he didn’t have the hands of a murderer and the final revelations confirm that there was no supernatural aspect to Paul’s behaviour, the whole notion was the product of Paul’s frankly demented imagination. That having the hands of another would feel strange is a sound enough notion (years ago, I had my nose rebuilt using cartilage from my ear and that felt peculiar enough), but believing that that he has become possessed by them when he learns that they once belonged to a murderer suggests that Paul is at the very least impressionable and hugely prejudiced – he believes in an instant that if a man committed murder then he must be inherently and contagiously evil – and at worst just a little bit round the twist. Then again, could this all be down to that skull fracture that the surgeon was able to fix, but which otherwise gets no mention in the story? Help me out here. Certainly, on the basis of this belief, it occurred to me that all Yvonne would have had to really do to cure Paul of his malaise was convince him that his new hands were not Vasseur’s after all but those of a saintly priest who died peacefully in his sleep. In that respect, the body part of Orlac that should be of most concern is not his hands but his deeply troubled mind.

Restored from both a 35mm print held by the Murnau Foundation and a 16mm print held by The Rohauer Collection, the 1080p 1.33:1 transfer here is intermittently impressive, but does vary a little in quality depending on the condition and format of the source material. Detail definition is often very good indeed, but does soften a little at times on what I suspect is some of the 16mm material, and while some shots are clean and free of damage, many display thin scratches and other small instances of minor damage, and a select few display more substantial signs of wear. The variance in the contrast is also pronounced, being a tad washed-out in some shots and punchy with beefy black levels in others, while in the best material it is close to being perfectly balanced. Given the age of the film and the source materials, this is not an issue and in no way distracting.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack features a new score by Johannes Kalitzke, one whose avant-garde influence and mix of electronic and traditional instruments most effectively enhances the film’s more unsettling scenes and particularly its expressionist overtones and occasionally has a whiff of György Ligeti about it. My only issue with it – one I’ve also had with similarly styled modern scores on horror-themed silent films – is an absence of emotional variance, which results in almost every scene, whatever its content, being given a sinister undertone by its musical accompaniment. Kalitzke also misses a trick when Paul listens to a recording of his piano-playing made before the accident and the score does not reflect what I couldn’t help thinking that he and we should be hearing.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default for the German intertitles.

Audio Commentary by Stephen Jones and Kim Newman

Having become rather used to the hugely entertaining and knowledgeable double-act of genre writers Stephen Jones and Kim Newman enthusing about films they love, it was interesting to hear Jones kick off on this one by admitting that he doesn’t like this film as much as his colleague does, a viewpoint he expands on several times during the course of the following ninety minutes. Newman reveals that he prepared for this commentary by reading Maurice Renard’s source novel and watching four of the six (so far) film adaptations, and is thus able to talk about the ways in which this and other film apatations diverge from the novel. Both men have plenty to say about the actors (Jones thinks Veidt is miscast and a bit wet here, Newman really likes aspects of his performance), the direction (Newman believes Wiene is undervalued, Jones is less convinced of his talent) and writer Maurice Renard, whom both make a case for regarding as the French H.G. Wells. We get information on a phenomenon known as alien hand syndrome, other notable films (and even one song) from this intriguing subgenre, the horror films of Conrad Veidt and the early stance he took against the Nazis, the film’s expressionist elements, and much more. Surprisingly, given that these two rarely pause for breath, there are a couple of gaps in the commentary, ones that occur abruptly enough (the second one comes almost mid-sentence) to suggest that something has been cut, perhaps for legal or accuracy reasons. Either way, this is a very fine companion to the film.

Extremities (26:23)

A video essay on the film by David Cairns and Fiona Watson, narrated by Jessica Martin, with extracts from Maurice Renard’s source novel read by Stephen McNicoll. Areas covered include the ‘affected by the transplanted limb/organ’ trope, Yvonne’s role in the story, the influence of eurhythmics and expressionism, Orlac’s transference of his affections from people to objects, the production design, the film’s influence on later works, the remakes, and more. Despite its formal presentation, there is plenty of real interest here.

Alternate Presentation (112:46)

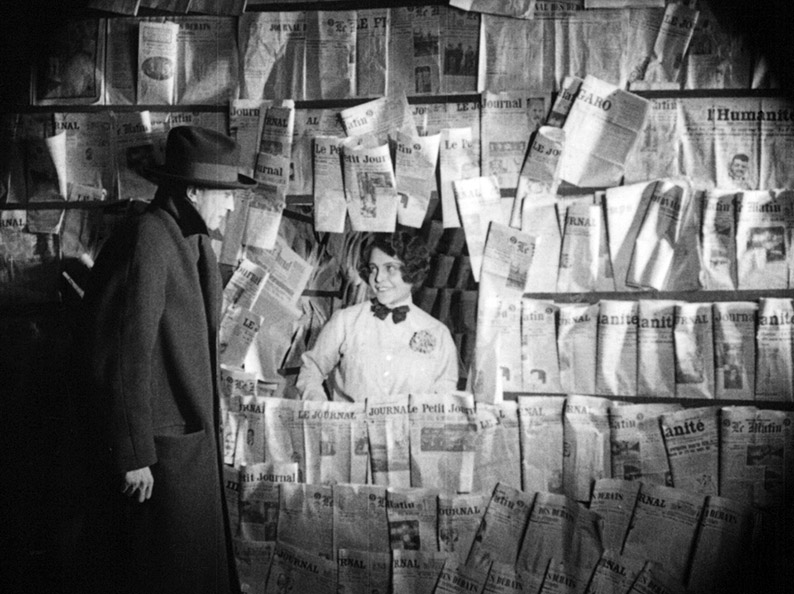

An alternative presentation of the film from a version held by the Murnau Foundation, which is presented in cleanly encoded standard definition with English intertitles, courtesy of FWMS and Kino Lorber and with a score by Paul Mercer. The first and most obvious difference here is that the titles, credits and intertitles are in English instead of the original German, but there are also several specially filmed inserts for what I presume was the film’s international release. The first is an on-screen dissolve from the German original of Paul’s opening scene letter to Yvonne to a handwritten English translation, a trick that is repeated when Paul receives a note informing him of the identity of the donor of his new hands and again when Regine writes a letter begging to be freed from her obligations (I’m sidestepping spoilers here for those who chose to avoid them earlier). Similarly, key newspaper headlines and text appear in German first and then dissolve to an English-language version, as does a note produced as potentially damning evidence late in the story, and when Paul reads his earlier letter to Yvonne and attempts to rewrite the first sentence with his new hands, the German original has been replaced with an English language version. Just occasionally, the creation of an English substitute was not feasible – a newspaper headline announcing Paul’s final concert that is accompanied by a photograph – and translation is thus provided by burned-in English subtitles. Typography enthusiasts will doubtless be interested to know that the fonts used for the opening titles and the intertitles also differ markedly from those in the German originals.

More significantly, this version of the film runs for close to 113 minutes, that’s almost 19 minutes longer than the restored German version. A little of this is accounted for by the extended time that the textual elements are held on screen for to allow for the German version to appear, then dissolve into the English translation and be held on screen long enough to be read. The majority, however, appears to consist of extra footage added to existing scenes, extending sequences and actions by a few seconds in a way that subtly alters the pacing but does not significantly change the course of the narrative. Occasionally, an addition will reveal new information – the early headline announcing that this will be Paul’s final concert, which does raise a few questions about why his subsequent inability to perform plunges him and Yvonne into poverty – while a direct comparison reveals that some shots are either alternative takes or filmed from a slightly different angle to the ones in the German release version (it was common to shoot films of the period with two cameras side-by-side to more easily facilitate a separate international edition).

Version Comparisons (13:49)

A side-by-side comparison between the two German language versions of the film used to create the one on this disc, the first being a 35mm print held by the Murnau Foundation and the second a 16mm print held by The Rohauer Collection. I’m guessing that the 16mm version was the basis for the Alternative Cut detailed above. This comparison was originally produced for Kino Lorber’s earlier DVD release by Bret Wood, who also provides a useful commentary in which he outlines the specifics of the differences between these two versions. Although structurally very similar, many shots on the 16mm print are taken from a slightly different angle, but occasionally this version also includes an alternative take of the shot used in the 35mm print, resulting in visible differences to how it is performed. Wood has clearly spent considerably more time on his comparison than I was able to on mine, and even highlights shots that were filmed at different frame rates on both versions, as well as noting changes in the editing of scenes and how that impacts on the story, characters and overall style. A fascinating piece and a valuable inclusion.

Also included with the release disc is a Collector’s Booklet featuring new writing by Philip Kemp, and Tim Lucas, but this was not available for review.

Despite the fame of its title for horror afficionados, I’d never got around to seeing The Hands of Orlac until I got my hands on this disc, and when I did I wasn’t quite sure how I felt about it, despite being seriously impressed by a couple of remarkable sequences and a smartly-devised set of final revelations. Subsequent viewings and the special features on this disc have given me a greater appreciation of elements that didn’t fully register the first time around, although my annoyance at the casual bypassing of one aspect of the ending still stands. A fascinating film, a decent transfer and some excellent special features make this one easy to recommend for the genre faithful.

|