| |

"I tell you the truth, it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God." |

| |

Jesus Christ – Matthew 19:23-24 |

It's worth keeping the above quote in mind when a money-driven multi-millionaire like David Cameron starts babbling on about "we Christians..." Sorry matey, but you can't have it both ways. I always find it comical when wealthy moralists quote biblical text to condemn lifestyles they disapprove of, yet when they encounter a passage that casts them in a bad light, well then Jesus was talking metaphorically, Jesus was mistaken, Jesus would make an exception for someone like them. I've even read a treatise penned by an American Christian capitalist (oxymoron alert) which claimed that what Jesus was really saying here was that we should all go out and make as much money as humanly possible. For them, Christianity is a socially accepted licence to pass hypocritical judgement on others, not a code by which they should be personally bound.

I, on the other hand, have no religious beliefs. Indeed, my relationship with religion of any denomination actually borders on the hostile. If you want to believe the world is controlled by an all-powerful deity and the concept that what we do in this life effects the next or our status in a theoretical afterlife, then go right ahead. You won't have my respect but you will have my largely indifferent tolerance. But start telling me how I should behave, live my life or what I should believe and you'll be walking into a world of pain. It's thus a little inevitable that I find traditional cinematic portrayals of religion a little hard to stomach. This is particularly true of the older Hollywood biblical stories and tales of religious intervention and salvation, which are often reverential to an almost preposterous degree. These are the films in which the afflicted look skyward and go dewy-eyed in awe, the soundtrack is awash with choirs that can only sing "aaahhhh", and the filmmakers tactfully avoid showing the face of Jesus or anything approaching an image of God (a bit like where Islam is right now, then). Such an approach gets in the way of many a good movie and even a few greats, for while I'll happily lap up the drama and spectacle of Ben-Hur, the moment it dives headlong into religion, I emotionally and intellectually tune out.

The paradox for me is that the bible would be an enthralling read were it not for all that religion, as a good many of its stories and characters are genuinely interesting. Principal amongst these is Jesus himself, as even if you don't buy him as the son of God (and I don't), he still cuts a fascinating figure as a progressive revolutionary who makes a humanist stand against an oppressive army of occupation and pays the ultimate price for his convictions. The problem with almost all film versions of this story is that they appear to have been made by unquestioning believers, who approach their subject as if grovelling for approval from a vengeful deity with a dodgy taste in cinema. As a result, the story and characters tend to take second place to cinematic hosanna, which for us non-believers at least makes them largely indigestible.

The Gospel According to Matthew (the 'St.' you'll often find in title translations was added in the UK against the director's wishes and is not part the original Italian Il vangelo secondo Matteo) is a rather different kettle of loaves and fishes. It was directed in 1964 by celebrated Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Pasolini was not a religious man. If that wasn't enough to put the heebie-jeebies into a God-fearing audience, he was also a Marxist. And a homosexual. Imagine their surprise, then, when he delivered a film that is both respectful of the source and yet free of the saccharine portrayal of religion found in so many previous cinematic bible stories. The result is a film that pulls off the seemingly impossible feat of being championed equally by believers and non-believers alike.

I'll make the assumption that this is one story that I need not provide a plot summary for, and frankly to get the best out of Pasolini's approach you'll need a good grounding in the text on which the film is based. Then again, maybe not. Pasolini's succinct blend of Italian neo-realism and economic minimalism may initially play like a whistle-stop tour of key events in the life of Christ, but this does an injustice to the fat-free economy of his storytelling style. Thus only five dialogue-free shots of Mary and Joseph are required to convey the human impact of the immaculate conception, while the recruiting of key disciples occupies only a few purposeful seconds of screen time. Elsewhere this paring-down makes narrative sense but does rob some scenes and characters of their context and back-stories, such as Salome's reasons for asking for Herod to bring her the head of John the Baptist, while you'll probably need to be familiar with the specifics of the Temptation of Christ to realise that the gruff looking disbeliever who questions his divinity is actually the devil.

There's a sometimes inescapable sense that we're watching a modern passion play being performed on location, but by stripping the story of its traditional cinematic pomp and fanfare, Pasolini humanises the protagonists and grounds their actions in an almost documentary reality. Key events are observed in wide shot or from an observational angle as if being recorded on the fly by a news film crew; we watch from a parapet as Jesus enters Jerusalem like a visiting celebrity, while the shocking brutality of the King Herod ordered slaughter of first born males is presented like a secretly filmed wartime atrocity. There are even moments here that anticipate the annoying current trend for faux-documentary wobble-vision, long lens shots seemingly grabbed by the camera crew as events unfolded before them.

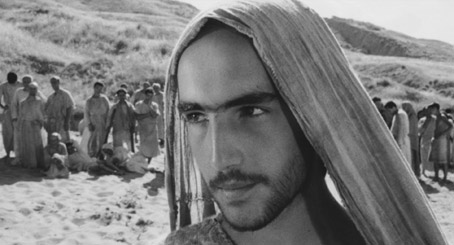

This air of realism is accentuated by the casting of non-professionals in many of the key roles, a wonderful array of weather-beaten faces that are light years from their groomed Hollywood equivalent and who convincingly sell the idea of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events. The logical exception is Jesus himself, bewitchingly played by Catalonian born newcomer Enrique Irazoqui, a man whose face radiates inner serenity and who conveys as much with just a look or a smile as he does with the conviction and words of his sermons.

Many have expressed surprise that such an authentic seeming film about the life of Christ could have been made by a Marxist, particularly given Marx's own assertion that "The first requisite for the happiness of the people is the abolition of religion." But given the similarities between the teachings of Jesus and aspects of Marxist philosophy – particularly their shared concern with the poor and the downtrodden – to me this has always made sense. This certainly comes through in Pasolini's presentation of Jesus as a potential revolutionary leader, though this is never hammered home, even in the potentially incendiary Cleansing of the Temple, when he angrily overturns the tables of money changers and accuses them of turning the temple into a den of thieves (one of many phrases quoted from the book of Matthew that has worked its way into common usage). And almost every line here is taken directly from the Gospel, which rebuts in advance any potential accusations that a politically motivated Pasolini was putting his own words into his lead character's mouth.

It's perhaps true that Pasolini's approach lacks the dramatic impact and engagement with character of the more romanticised biblical tales, but it still captivates through its storytelling economy and its visual and aural poetry, notably the evocative location work and an eclectic score that ranges from Bach's Mass in B Minor to the Odetta's haunting rendition of Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child. And for all its small costume and character anachronisms, the film's documentary-like handling of the most iconic of scenes gives them a freshness and dramatic vibrancy you'll not find elsewhere. Occasionally this has the effect of enhancing our sense of awe, as when Jesus walks across Lake Galilee to the astonishment of his followers, a scene whose handling here makes it look like the real deal. It's a technique put to particularly memorable use during Jesus's arrest, which is observed exclusively from Peter's viewpoint as he mingles with the watching crowd. The sequence that follows, in which Peter breaks down and weeps after fulfilling the prophecy that he would disown Jesus three times, is possibly the film's most emotionally affecting scene.

Pasolini's reverence for the source material just occasionally tips the film towards the idolatry he otherwise seems determined to avoid, perhaps reflecting his claim that he was "an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for a belief." But it's kept on track by its potent air of realism, the bewitching handling of individual scenes, a sly ambiguity over certain aspects of the story (the curing of a leper is achieved through cinematic sleight-of-hand rather than anything that Jesus is actually shown to have done), and the overriding sense that we are watching the story of a man who is doomed from the moment he first begins preaching brotherly love. "Catholicism teaches us that beyond death there is another world," the director once stated, tellingly adding, "in my films there are no such promises." A gospel story it may be, but it's still every inch a Pasolini film.

A clean and attractive 1.85:1 monochrome transfer with a very pleasing tonal range. The level of detail is consistent more with a top-flight DVD than a showcase Blu-ray, which may well be down to the original material and is certainly consistent with its semi-documentary aesthetic. The punchy contrast range ensures solid blacks but does occasionally result in some slight burn-out on the brightest elements of sunlight exteriors. Not a show-stopping transfer, but pleasing nonetheless, and certainly the best I've seen the film look.

The linear PCM mono soundtrack is inevitably a little narrow in its range (no deep bass notes here) but feels right for the vintage and the tone of the film. The music and dialogue are clear, the soundtrack itself free of damage, and you'll only hear a slight background hiss if you crank up the volume.

Sopralluoghi in Palestina (53:37)

A documentary shot in 1963 that follows Pasolini as he scouted Palestinian locations for the film, which would ultimately end up being shot entirely in Southern Italy. A fascinating and valuable film document in its own right, it records not only Pasolini's approach to location scouting, but his thoughts on the process and a few very telling political observations (in a comment with an unfortunate contemporary resonance he observes at one point that Syrian soldiers are shooting at Jews, and notes that industrial plants have been build where Sodom and Gomorrah once stood). His interaction with the locals gives the film an ethnographic element, while a guide named Don Andrea links locations to specific gospel events. The flash frames and sudden camera moves at the end of what seems like every other shot suggests that almost every frame of shot footage was used.

Original Trailer (5:06)

A Italian trailer of substantial length made up of sizeable extracts and featuring a voice-over that notes that the film has "surprisingly authentic and fascinating characters."

Newsreel (1:16)

A brief extract from the la settimana income weekly newsreel in which Pasolini talks about filming the Sopralluoghi in Palestina documentary.

Outtakes (3:17)

A selection of silent unused footage shot for the Sopralluoghi in Palestina documentary. Again most of the shots end with flash frames and sudden camera movements as the camera is switched off.

Booklet

Oh I love these booklets. A few years ago you'd have paid a couple of quid to buy their equivalent at the BFI bookshop and would have been thoroughly satisfied with the purchase. Together with the on-disc extras, they turn each release into a bit of an event and give the best of them a sense of thrilling completeness. The one here is no exception, a typically handsome 36-page document that includes credits for the film, some notes on the title and the small but significant change it underwent in the UK, an extract from a letter sent by Pasolini to Lucio S. Caruso of the Catholic Pro Civitate Christiana in Assisi, an essay on the film by Pasquale Iannone, two sizeable extracts from the 1969 Pasolini on Pasolini: Interviews with Oswald Stack in which Pasolini answers questions about the film, a reproduction of Matthew, Chapter 28, notes on viewing and some high quality stills. Fabulous.

For me, still the best film interpretation of a biblical story and just possibly my favourite Pasolini film, The Gospel According to Matthew remains an enthralling work and still feels as cinematically adventurous as it ever did. The transfer is not as super-sharp as I was perhaps hoping for, but it still looks good and feels appropriate for Pasolini's chosen documentary aesthetic, and the extra features and booklet are all top notch. Thus even for us confirmed non-believers, this has to come enthusiastically recommended.

|