| "What are we if we don't try and help others? We're nothing… nothing at all." |

| Henry Marsh, neurosurgeon |

Death is the appalling inevitability of life, but there are those who make a stand against it on our behalf, who pull us back from a brink that we would otherwise tumble unwillingly into. Think of firefighters who rush into burning buildings to rescue those asphyxiating from smoke inhalation, or to get more specific, the ambulancemen who decades ago rushed my father to hospital just in time to save him from dying from a serious wound from which he had lost a spectacular amount of blood. And then there are the doctors, the specialists and the surgeons who recognise the warning signs, diagnose the illnesses, and perform the operations that save and extend our lives, assuming they are in a position to do so, of course. And these people often go unsung. Years ago, my mother was rushed to hospital with serious breathing difficulties and taken straight to casualty, where she began losing consciousness and failing to respond to stimuli of any kind. It became clear that she was going downhill fast, and in order to do their jobs without distraction, the nurses in attendance requested that I leave. It was at this point that I realised that I might be about to lose her. Fifteen minutes of increasingly distressed pacing about in the waiting area and a tearful call to my sister later, I heard one of the nurses calling my mother's name, and in a tone that clearly indicated an expected response. I returned to her bedside to find her weak but conscious again. What had happened? Just after I departed, a passing doctor had stopped his journey to see what could be done, and based on what he read in her notes, made an educated guess that she might be having a hitherto undiagnosed allergic reaction to morphine. He thus administered what was effectively a counter-morphine drug, and it turned out he was bang on the money. This man had walked into the ward, made a quick decision that I was afterwards assured had saved my mother's life, then moved on to administer his life-saving wisdom elsewhere without a hint of ego or fanfare. He gave my mother the greatest gift of all and almost had me weeping with relief and gratitude at the time, and I never even learned his name.

One name I have a feeling I shall be remembering for some time is that of Henry Marsh, an NHS neurosurgeon who was so shocked by what he saw when he visited one a state hospital while on a professional visit to Ukraine in 1992 that he became instantly determined to do whatever he could to help these people. He thus began making regular visits to the country, collecting and transporting surplus equipment, and giving his own time freely to meet patients with a range of serious neurological conditions to assist with diagnosis and operate on those whom he believed he could help. As we join him in director Geoffrey Smith's mesmerising and moving 2007 documentary portrait, he's packing an operator's chair in a wooden case of his own making ("I like the smell and feel of wood… I've always loved using tools") to send to Kyiv as he preps for another visit. Being driven to the airport in Kyiv to meet him, meanwhile, is his Ukrainian counterpart, Dr. Igor Petrovich, a committed surgeon whose determination and rejection of state medical ideology has repeatedly landed him in trouble and even made him the target of death threats, and who has been learning new surgical techniques from Henry since the two first met. 400km west of the city in Zolochiv, meanwhile, financially strapped 20-something Marian lives in hope that Henry will agree to operate and remove the brain tumour that is causing his epilepsy and slowly killing him.

Initially, the film moves between these three perspectives, as Igor explains how his relationship with Henry has grown to the point where they are now more like brothers, Henry loses his rag with the frustratingly bureaucratic job plan he is expected fill out on a stubbornly uncooperative computer, and Marian expresses his newly discovered longing for life and attends a church service where prayers are offered for a successful operation and recovery. Once Igor meets Henry at Kyiv airport, their stories entwine into a single strand that has the two men working as a team at the hospital in which Igor is based, and rekindling their long-standing friendship outside of it. Whether sharing a meal prepared by Igor's wife at his home, visiting the location of a proposed new hospital, or shopping at a local market for tools they can adapt for use in the equipment-starved operating theatre, the bond between the two is quickly and firmly established, simultaneously putting a human face to men who are too often defined solely by their profession.

It's in the surgeries they hold with packed corridors of hopeful patients that the most difficult aspect of their job first becomes evident, as Henry examines the brain scans of the grandchild of a middle-aged woman who sits waiting expectantly for a diagnosis and a course of treatment. Noting that the tumour is on the brain stem, Henry tells Igor that it is basically inoperable, and states sadly but matter-of-factly, "I'm afraid that the child has less than a year to live," which Igor then has to translate for the unsurprisingly tearful woman. "But obviously," adds Henry with genuine feeling, "as parents and as grandparents we find it very, very difficult to do nothing. It's very hard." "So what do? Something to do?" the still desperately hopeful woman asks, only for Henry to tell Igor, with obvious discomfort but professional directness, "My opinion is there is nothing to do but wait for the child to die," tragic words that Igor then soberly translates. "Life can be very cruel," Henry adds, making me wonder just how many times he's had to deliver similarly terrible news to hopeful patients. Then, in the first of a handful of moments that almost brought me to tears, the deeply shaken woman wipes her face and says, "Thank you. Thank you very much. I'm sorry to trouble you." And this won't be the last time we'll see such news delivered. A later diagnosis of a strikingly attractive young woman in her early 20s, whom Igor seriously struggles to be as honest with as his mentor about her condition, genuinely came close to tearing my heart in two.

It's revealed early on that, despite the many successful operations Henry must have performed to draw the number of potential patients his every visit attracts, one of the key things that drives him is the memory of a young Ukrainian girl named Tanja, who died regardless of his perhaps overconfident best efforts and whose mother Katja he feels compelled to visit on this trip. That he is able to recall his first meeting Tanja, the details of her treatment and how things ultimately went wrong in such melancholic detail would alone make for compelling viewing, but it turns out there is more. Many of Henry's meetings with Tanja and Katja were captured on videotape by Henry and an unnamed colleague, footage whose inclusion here transforms a sad memory into a mini-documentary of its own, putting faces to the names and starkly illustrating the increasing severity of Tanja's condition. This also feeds into Henry's belief that you learn far more from your failures than your successes, a truism that can be painful to experience but is without question valuable to build on.

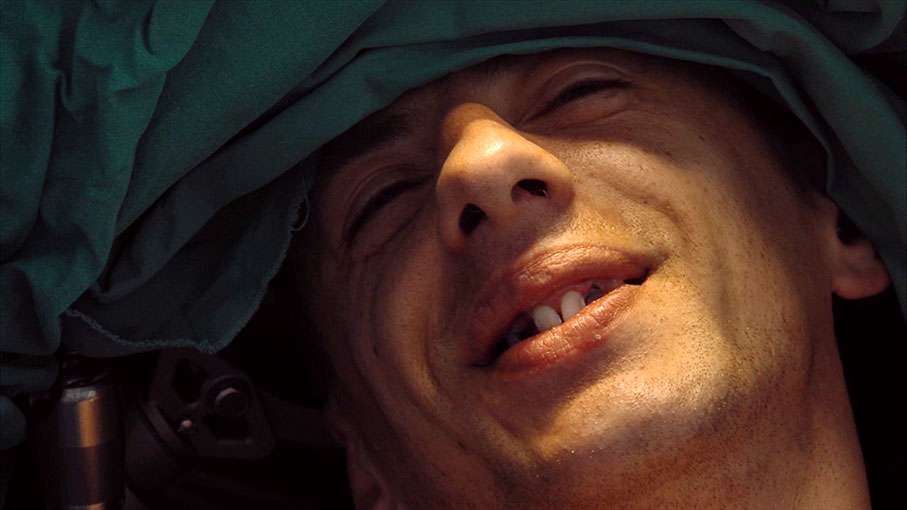

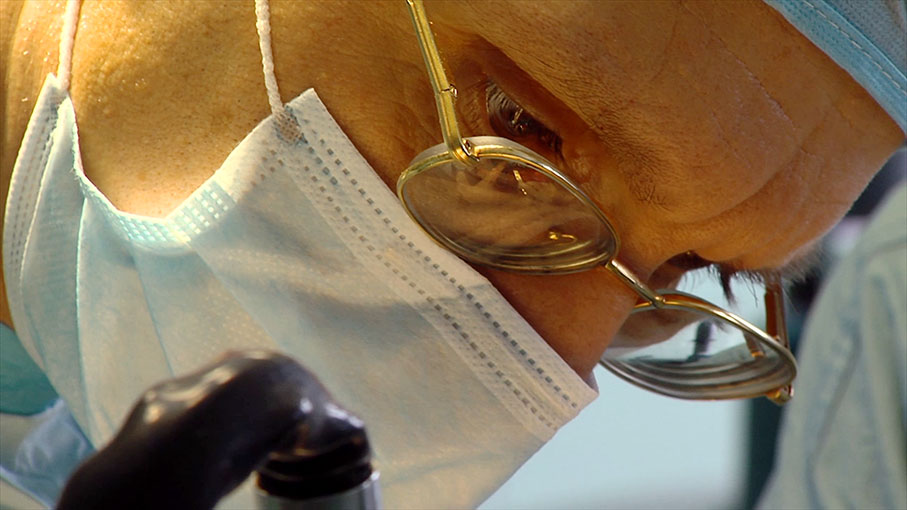

As indicated by the opening scenes, the narrative centrepiece of the film is Marian's admission to hospital and the operation to remove his tumour. Whether he will be admitted at all initially depends not only on his acceptance of the risk that his personality, intellect or physical movement might be impaired should the operation be unsuccessful, but also that he would be willing to remain conscious throughout the operation. He won't feel any pain, Henry assures him, but the noise and vibration of the drill needed to open his skull might feel unpleasant. If this sets alarm bells ringing, know that prior to this there is a brief scene that acts almost as a litmus test for the viewer, where we watch as the skull of an unconscious patient is drilled into in a British hospital under Henry's supervision. If you're squeamish about operations, you might want to hide your eyes and ears for a few seconds here, especially once they start cutting the skull with a surgical wire saw. When we get to Marian's operation, there are some unsurprisingly graphic shots of the surgery, but Smith is more interested in the faces of the doctors and their patient here. Indeed, the thing that startled me the most was that with no access to the air-driven medical drill used in European hospitals to cut through the tough bone of the human skull, Igor is forced to use the Bosch cordless power drill that he and Henry picked up at the local market. What this whole sequence does impeccably is build real tension over whether the operation will be a success, something that we know from Henry's past experience with Tanja and his description of the risks involved is far from done deal. By this point, I was seriously invested in the easily likable Marian's fate, and salute his bravery for so willingly agreeing to remain conscious while surgeons are drilling holes in his head and cutting material out of his brain, fully aware that it could leave him paralysed or mentally incapacitated. Knowing that Henry encouraged director Geoffrey Smith to keep filming even if things went badly only added to my nervousness here.

The English Surgeon is an observational documentary par excellence, one whose easy intimacy with its title character marks it as something more. Although we never here director Smith speak within the film (for that, see the special features on this disc), his presence is still strongly felt, his unheard questions to Henry prompting responses whose honesty speaks volumes about the level of trust that Smith must have built with his subject. You get the impression that Henry not only has faith in Smith as a documentarian, but also that he genuinely likes him as a person, so feels able to talk openly about the risks associated with his work whilst sitting with a glass of wine in his hand in his living room one evening. The effect of this is to makes feel like guests that Henry has invited into his workplace and his home to share his thoughts on his profession and his mission. This engagement with the subject was enhanced further for me by a GP with whom I was once friends, a man who shared some of Henry's facial features and whose manner and vocal delivery were similar, including his sympathetic directness when delivering bad news.

The English Surgeon is a rare example of a film that does everything an observational documentary should do, and does so without the use of distracting flashy graphics or postmodernist visual tics. Smith and his cinematographer Graham Day (Smith also operated a second camera on certain setups) do a marvellous job of capturing faces, expressions, reactions and small details in a manner that makes the filmmakers – save for those moments when the subjects talk directly to them – feel truly invisible to those they are filming. Kathy O'Shea's editing is spot-on throughout, neatly juxtaposing shots at the start in a visual representation of the meeting of doctors and patient that is soon to occur, and at one point tellingly cutting to the SD footage of Tanja and Katja as Henry and Igor contemplate the emotional weight of having to deliver bad news. Topping things off is a gorgeously understated score by Nick Cave (yes, that Nick Cave) and Warren Ellis, which quietly underscores the mood and emotion of scenes without forcefully pushing buttons in the Hollywood feature mode.

In his interview on the special features, Henry states emphatically that he hates surgeons being portrayed as heroes, and one of the principal achievements of the film is that is breaks down some of the mythos that surrounds neurosurgery to show it as a medical procedure performed by good people not unlike ourselves. The peek it offers into the then run-down Ukrainian healthcare system, where serious medical conditions progress to an advanced and sometimes irreversible stage in part because the cost of treatment is beyond the pockets of ordinary people, should serve as a reminder of what we may end up going back to if our present government succeeds in its continuing efforts to run the NHS into the ground. But the core of the film remains the surgeon of the title, an immensely personable, highly skilled and dedicated humanitarian who absolutely lives by the quoted coda at the top of this review. Since the film was made, of course, Ukraine has been the victim of a brutal invasion by Russian forces, which has resulted in thousands of deaths and injuries on both sides, and now threatens the lives of the very people that Henry did all he could to save, and the country that he has come to love. There are real lessons here, for us as individuals, as well as for society and humanity as a whole. Indeed, at a time when we are constantly badgered by politicians and their client media to distrust and dislike just about anyone who differs from their narrowly defined norm and blame them for all our ills, this extraordinary film offers a deeply affecting corrective that we all could and should do well to learn from.

Given the year of production and the fact that this was originally produced for the BBC's Storyville documentary strand, I suspect The English Surgeon was shot on HD video rather than film, though it does have an attractively filmic look at times, possibly the result of some quality post-production grading. That said, the HD material is occasionally supplemented by what looks like footage from lower resolution action cameras used to record conversations between Igor and Henry as they drive, and older SD footage of Henry's earlier meetings with Tanja and Katja, some of which also displays some rather coarse digital grain. Given that the film was shot under available light in a variety of lighting conditions, including living rooms at night, the sharpness and colour range does vary a little throughout, but even at its most challenging the image on this 1.78:1 transfer is robust. If you truly want to judge its quality, take a look at the early film shot of the face of Igor's pet cat, or the close-ups of faces during Marian's operation, which are pin-sharp with excellent colour and contrast. Given the variance in the material, this is a terrific job all round.

The Linear PCM 2.0 stereo soundtrack is also of excellent quality and is impressively mixed, with always clear dialogue never lost to background location sound or Cave and Ellis's score, the only aspect of the soundtrack that appears to have clear if subtly employed stereo separation.

There are clear burned-in English subtitles for the Ukrainian dialogue, but no optional subtitles for the deaf or hearing impaired.

Interview with surgeon Henry Marsh (14:14)

A new interview with Henry Marsh, who talks straight to camera, presumably responding to unheard questions, his answers to which are every bit as open and up-front here as he is in the film. He recalls his first meetings with director Geoffrey Smith, notes that he trusted him to do his job without interference, and that he encouraged him to also show if things went badly. As noted in the review, his one stipulation was that Smith should not portray surgeons as heroes, which he hates, as he believes that patients are more heroic. He reveals that the decision to shoot in Ukraine allowed them to film situations that would have been closed to them in Europe, and outlines why he was drawn to neurosurgery as a young man, only to find himself unprepared for the risks and failures that lay ahead. Despite retiring as a surgeon three years ago, he assures us that not a day goes by when he doesn't think about one of his patients for whom things did not go well. He discusses his experience in Ukraine and his working relationship with Igor, and reflects again on the failed operation on Tanja, reenforcing the sometimes uncomfortable truth that we learn more from our mistakes than our successes. The interview also has a very personal sting in its tail, one that genuinely blindsided me.

Interview with director Geoffrey Smith (25:10)

Filmed in similar to-camera style as the interview with Henry Marsh, here The English Surgeon director Geoffrey Smith outlines why he made the film, how it was inspired in part by what he calls the sacred relationship between surgeons and those whose lives they save, and why he was attracted to the notion of two strangers coming together in order that one might save the life of the other. He notes that Henry has an obsession with the truth and that he believes we should be honest and learn from our mistakes, and that he claims to carry a graveyard in his head of those he has failed to save. He talks revealingly about his approach to observational documentary, how he shot the scenes in the consulting room, Nick Cave's involvement and his score for the film, and recalls the moving experiences he and Henry had at festival screenings. There's plenty more of interest here.

Trailer (2:20)

An impeccably assembled trailer that captures the essence of the film and would absolutely have sold it to me as a must-watch, which it is, of course.

Also included is a 12-page Booklet featuring a marvellous essay on the film and its director by film writer Trevor Johnston, as well as the main credits for the feature and the interviews.

An impeccable slice of observational documentary that involves and educates, tells a genuinely gripping and moving story, and paints an inspiring picture of a man whose example and philosophy of life we could all learn something from. On the face of it, an unexpected release from Second Run, but an excellent one that I genuinely can't recommend enough, for Smith's remarkable film, for Second Run's faultless presentation, and for the first-rate special features.

For the record, the title of this review is respectfully borrowed from director Geoffrey Smith, who in his interview on this disc uses this phrase to describe what The English Surgeon is really about.

|