|

In may seem a little peculiar to start comparing legendary Japanese filmmaker Imamura Shōhei to perennially cheerful The Blues Brothers and An American Werewolf in London director John Landis. Yet there's a sequence about ten minutes into Imamura's Palme D'Or winning 1997 Unagi [The Eel] that can't help but recall a similar one from Landis's undervalued 1985 Into the Night, particularly as it occurs at a similar point in the narratives of both films. In Landis's movie, office worker Ed Okin comes home unexpectedly early one day, peers in through his bedroom window and sees his wife having sex with another man. In Imamura's film, office worker Yamashita Takuro (Yakusho Kōji) comes home early from his nightly fishing trip, peers in through his bedroom window and, well, you can guess the rest. There is, however, a key difference here, as while Ed was unaware of his wife's infidelity and thus caught completely on the hop by what he sees, Takuro has been tipped off to the affair by an anonymous letter, and once the respective husbands make their sobering discoveries, the two films follow starkly different paths. In Landis's movie, the sex is heard rather than seen, and the focus instead is on Ed's crestfallen reaction. In Imamura's, the sex is not only shown but enthusiastically performed and punishingly lingered on, which has the effect of aligning us with Takuro's humiliation and sense of betrayal. And while Ed walks away with an air of dazed defeat, Takuro takes a knife, marches into the bedroom, and angrily stabs his wife Emiko (Terada Chiho) to death. A short while later, in a sequence that feels both surrealistic and quintessentially Japanese, he walks into a local police station, covered in enough blood to suggest he was standing two feet away from an exploding buffalo, and formally states his name, announces that he has killed his wife, hands over the murder weapon, and turns himself in.

Eight years later (in Japan, a rehabilitative approach to jail time is often taken, resulting in what for westerners may seem surprisingly short sentences for serious crimes), Takuro is released on a two year probation and relocates to a quiet rural hamlet where only his locally-based parole officer – the Reverend Nakajima Jiro (Tokita Fujio) – is aware of his past crime. Here, he uses money left to him by his late mother to buy an abandoned riverside shop, which he restores and draws on a skill he learned in prison to set himself up as a barber, in which role he politely interacts with a community that he nonetheless remains socially distanced from. His only companion is an eel that he kept as an unofficial pet during his time in prison, an animal with which he appears to be able to telepathically communicate.

Okay, a little clarification is required here. Takuro is no Japanese Dr. Doolittle, nor does he have a supernatural bond with freshwater fish. His connection to his eel is more a psychological one, his past sins having left him withdrawn enough to ensure that the animal has become the one creature he feels able to open up to. Questioned on it by Jiro, Takuro tells him simply, "He listens to what I say. He doesn’t say what I don’t want to hear."

One day, Takuro is fishing for food for his eel when he discovers the body of a young woman lying in the riverside reeds. Recalling the prison warden’s warning to avoid trouble at all costs, he returns to the barbershop and asks three of his regular customers to witness his discovery, and thanks to their swift action and the resulting medical help, this would-be suicide, Keiko (Shimizu Misa), makes a full recovery. Regretting her actions and looking to put her troubled past behind her, she moves in with Jiro and his wife Misako (Baishō Mitsuko), who ask Takuro if he would be willing to help Keiko by employing her at his shop. Deeply troubled by her physical resemblance to his late wife Emiko, Takuro is initially reluctant but ultimately agrees and soon finds himself working well with his new assistant. But his slow rehabilitation and potential future with Keiko is threatened when the truth about his past risks being exposed, and Keiko’s own troubled past shows signs of catching up to her.

If the story revolved around that last paragraph alone then we'd be on very familiar ground, as tales of mutually attracted individuals who run into problems on the road to contentment have been two-a-penny since cinema's earliest days. Even the main location – a barbershop that doubles as a communal hub – has since become a familiar component in American cinema, but as you would expect with a director of Imamura’s standing, here it's not that simple. From an early stage, Takuro is presented in a sympathetic light, as a quiet and politely apologetic figure who has been left damaged by his past deeds and his time behind bars (and believe me, even a brief spell in a Japanese prison is no picnic). And yet almost the first thing we watch him do is stab his wife to death, a selfish and extreme response triggered by his own wounded pride, and just a few minutes of screen time later – his prison term passes in a flash – we're encouraged to engage with him on an empathetic level. That this proves so disarmingly easy to do, and that we remain curiously untroubled by his earlier crime, is probably a ripe subject for an in-depth psychoanalytical essay, one I certainly do not feel qualified to write.

What subsequently unfolds is a quietly captivating portrait of Takuro's slow social adjustment and his developing friendship with the small band of misfits who gravitate to his shop. It’s an upbeat and enjoyably eclectic group consisting of grizzle-faced carpenter and night-time fisherman Takada (Satō Makoto), quiff-haired wannabe playboy Yuji (Aikawa Shō), and cognitively challenged young Masaki (Kobayashi Ken), who spends his time building an eye-catching beacon to attract the attention of passing UFOs. This engaging character texturing ensures that the tone remains a lot lighter than you might expect of an emotional journey such as this, with all three hangers-on being reflective of aspects of Takuro's personality that he has yet to come to terms with. This is neatly highlighted by a brief conversation between Takuro and Masaki about the latter’s UFO fixation – "Aren't you really just afraid of making friends with people?" Takuro asks him, to which Masaki responds, "Just like you, right?"

Despite Takuro’s initial apprehension, Keiko quickly proves an asset to the shop, and the regulars begin openly speculating about the nature of her relationship with her self-conscious employer. Complications arise in the shape of bitter ex-convict Takasaki (Emoto Akira), who threatens to reveal all about Takuro's past, and the arrival of Keiko's criminal ex-lover Dojima (Taguchi Tomorowo) and his attempts to con her mentally unstable mother Fumie (Etsuko Ichihara) out of her savings. Just how, and indeed if, Takuro will resolve his inner conflict becomes the real focus of the film – Keiko is clearly attracted to him, and in spite of his determination to keep her at a distance, he seems to like her, but their respective past lives repeatedly threaten to cloud the picture. At one point, a rattled Takuro sternly orders Keiko to leave the barbershop whilst in the process of sharpening a razor for the following day's work, and I momentarily feared for her immediate safety, and when she starts preparing bento lunches in the manner of Takuro's late wife, the possibility that history might be repeating itself becomes a real concern. It all comes to a head when Dojima, accompanied by two of his cronies, shows up at the barbershop angrily demanding that the absent Keiko hand over her mother’s money, a confrontation that blows up into an extended brawl involving just about everyone (the gruff, no-nonsense Takada really comes into his own here), and whose chaotic playground scrappiness transforms a theoretically serious scene into a small comic delight.

That Unagi won Imamura his second Palme D'Or was something I was once a little surprised by, believing back then as I did that, for all its many virtues, the film was neither as dynamic nor as adventurous as a good many of the director's earlier works. It does share several of their underlying themes, albeit in toned-down form, from the focus on social outsiders to the symbolic role played by animals and the frank and unglamorous presentation of sex, elements that were given fuller realisation in the director’s 1968 Profound Desires of the Gods [Kamigami no fukaki yokubō] and his first Palme D'Or winner, the 1993 The Ballad of Narayama [Narayama bushikō]. Here, the prime focus on a single individual and his offbeat entourage inevitably results in a reduced sense of scale when compared to the ensemble work in the above-mentioned films, and even earlier features like the 1961 Pigs and Battleships [Buta to gunkan] or his 1958 debut feature, Stolen Desire [Nusumareta yokujō]. We also never get as discomfortingly close to our troubled lead character as we did to serial killer Enokizu Iwao in Imamura’s 1979 Vengeance is Mine [Fukushū suru wa ware ni ari].

But all these years later, it occurs to me that this was always the point, a deliberate move on the part of Imamura and his co-writers Tengan Daisuke (Imamura’s first son and a director in his own right) and Tomikawa Motofumi. Despite being accepted by the small community into which he has relocated, Takuro remains emotionally distanced from it, resistant to the attentions of Keiko and never openly expressing positive feelings towards any of those who have come to consider him a friend. That he remains a largely closed book to us is thus an appropriate reflection of how he is doubtless perceived by those in his immediate circle. Indeed, the only time we see him express genuine warmth and affection is for his titular eel, the symbolism of which is open to a range of interpretations. Quite how he obtained the animal in the first place is never revealed (I can’t imagine that they’re swimming around in the prison baths), but while he was incarcerated this animal clearly became a close companion, a creature with whom he could share his thoughts, safe in the knowledge that he could effectively shape both sides of the conversation. Later, notably when the he warmly cosies up to the eel’s tank at night, there’s almost a feeling that the animal has come to represent fonder memories of his late wife, a notion seemingly borne out by his horror at the idea of catching eels by stabbing them with a spear, and by the metaphoric nature of a nighttime river sequence in the final ten minutes, one I’m tactfully going to avoid revealing further details of here. Of course, it’s also quite possible to take Takuro’s bond with the animal at face value and see it as evidence of mental instability and an inability on his part to distinguish fantasy from reality, which may well explain his extreme reaction to his wife’s infidelity, but also raises problematic questions for the viewing audience regarding how much of what both we and he sees is actually taking place, and how much is the product of Takuro’s imagination.

Either way, as a portrait of loneliness, redemption, rehabilitation, and the special bonds and strengths of small communities, Unagi works divinely, and despite its shocking early act of violence, it remains one of Imamura's most accessible and enjoyable films. Takuro's eel tank hallucinations aside (one of which briefly echoes a memorable sequence from the previous year's Trainspotting), the handling is resolutely low-key and reality-grounded, with The Ballad of Narayama cinematographer Komatsubara Shigeru’s largely immobile camera quietly observing Takuro in predominantly wide and mid-shot, rarely taking the traditional cinematic route to character connection of facial close-ups.

As ever with Imamura, the film is impeccably cast and superbly performed. I have a particular liking for veteran actor Satō Makoto's turn as the grizzled Takada, and a soft spot for the unnamed young boy who steals the only scene he appears in by cheerfully bellowing his thanks for a sweet potato snack. Shimizu Misa brings a humble truthfulness to Keiko that I found quietly entrancing, which makes Takuro’s reluctance to respond to her overtures all the more frustrating, and the late film revelation about her true social standing genuinely surprising. But anchoring the film and showing commendable restraint as Takuro is the ever-impressive Yakusho Kōji, a hugely talented, consistently busy and versatile stage performer whose big break as a cinematic leading man came in 1996 with Suō Masayuki’s Shall We Dansu? and was consolidated the following year with lead roles in Morita Yoshimitsu’s Lost Paradise [Shitsurakuen], Kurosawa Kiyoshi's mesmerising Cure, and of course, Unagi. Now in his late 60s, he’s still a consistently busy actor (he made five films and two TV series in 2023 alone), and last year he won acclaim and multiple awards for his portrayal of a humble Tōkyō toilet cleaner in Wim Wenders’ quietly wonderful Perfect Days.

Unagi will always have a special place in my heart for being the film that belatedly introduced me to the cinema of Imamura Shōhei when the film society I used to co-run screened a 35mm print for a well-attended and appreciative audience, and since then, many more of Imamura's films have been made available in the UK, primarily through Eureka's Masters of Cinema label. That so many of these earlier features now feel even more exciting and innovative is perhaps unsurprising, but should not take away from Imamura’s achievement here – he was 70 when he made Unagi, but still delivered a thoughtful, captivating, multi-layered and entertaining work that shines in its performances, its storytelling, and – in its belief that no-one should be denied the possibility of redemption – its gentle humanity. Just spare a thought for Emiko, who although the catalyst for the story, died a violent and unjustified death at her husband's hands for nothing more sinister than having the hots for another man.

Unagi was released theatrically in Japan on 24 May 1997 with a running time of 117 minutes, which was also the version released for the international market, and thus the one that I first saw. Later that same year, the film was re-released in a new 134 minute director’s cut supervised by Imamura. Now I’ll be honest and admit that when reviewing films that I’m new to that are presented in alternative cuts on the disc in question, actually tracking all of the differences can be a hugely time-consuming challenge, so I’m always grateful when the disc includes a featurette that details them for me. There is no such featurette on Radiance’s disc, but Unagi is a film I have seen in its theatrical cut several times, and as I’ve yet to come across a definitive list of the differences between the two cuts, I thought I’d have a stab at making one myself, which I hope to upload to the film’s IMDb page in the coming days. Watching both versions back to back made it easier to spot the changes made in the director’s cut, on which I made extensive notes, but to be sure I dragged both cuts onto the same timeline in Final Cut Pro and went through them scene by scene to confirm, refine, and add to the observations I had made.

The alterations are often subtle, but none is superfluous, and all serve to either clarify points, expand on character detail, or alter the tone of a particular scene. This does sometimes mean that background details alluded to in the original are more plainly spelt out in the director’s cut, which occasionally plays a little like clarification of cultural elements for an international audience. Often they serve to reinforce character detail that has been established earlier, but this is never overstated or clumsily handled – if you came to the director’s cut first, I’d wager you would not feel it needed trimming. Perhaps the most unexpectedly impactful change occurs during Takuro’s observation of Emiko’s sexual encounter and her subsequent brutal murder, which in the theatrical cut was accompanied by a thriller-like score by composer Ikebe Shinichirō, while in the director’s cut the music for this sequence has been completely removed, which has the effect of making the sequence feel even more disturbing.

Listed below are all of the changes that I observed in the director’s cut, and I have included the length of any additional material where I think it may be relevant. I’ll admit up front that I’ve probably missed a few of the more subtle alterations – on a few occasions, scenes run almost exactly as they did before but with small changes made to the editing rhythm. It’s a long list that assumes familiarity with at least one cut of the film and its characters, and inevitably includes its share of spoilers, so I’d advise against reading this before a first viewing. For the record, I do prefer the director’s cut, particularly for the additional character details it provides and the small improvements it makes to certain sequences.

|

The opening workplace scene begins with an additional establishing wide shot of the open-plan office in which Takuro works. |

|

The last few seconds of the mid-shot of Yamishita working at his desk have been trimmed. |

|

The music score that accompanies Takuro reading the poison pen letter on the train and his subsequent arrival home has been removed |

|

The audio recall of a line from the poison pen letter, “He drives a white sedan,” when Takuro discovers Emiko’s lover’s car has been removed (this did feel like an overstatement in the original cut and in my humble opinion works far better this way). |

|

As noted above, the thriller style music score that previously accompanied the scene in which Takuro discovers his wife’s infidelity and kills her has been removed. |

|

Between the sequence in which Takuro turns himself in and the “8 years later” caption that immediately follows, an additional shot of him sitting contemplatively on the floor of his prison cell has been added. |

|

The shot of Takuro being driven away from the prison by Jiro has been extended by 18 seconds to allow the two prison officers who see him off to comment on the length of his sentence and his status as a model prisoner. |

|

The conversation between Jiro and Takuro in the car as they drive begins 29 seconds earlier and provides information about Takuro’s brother, whose existence is not acknowledged until they reach the run-down barbershop in the original cut. It also explains why the brother did not come to the prison to meet Takuro on his release. |

|

The sequence in which Jiro and Takuro stop for food now begins 35 seconds earlier, and includes Jiro pulling up outside the store, getting out of the car and suggesting to Takuro that they stretch their legs. |

|

The shot in which Jiro pulls up outside his temple and invites Takuro inside has been slightly extended – Takuro now delivers the line, “My eel doesn’t look so good” in the car instead of over the next shot of him refreshing the water in the bag containing the eel. |

|

The subsequent shot of Jiro and Takuro walking begins 13 seconds earlier, and the music that accompanied the first part of their walk has been removed, only resurfacing in the flashback to Takuro’s prison days. |

|

The flashback of the prisoners regimentally marching in the exercise yard is 17 seconds longer at the front end and 5 seconds shorter at the tail end. |

| |

|

|

After Jiro and Takuro reach the barbershop and Jiro gives Takuro his bank book, there is one-and-a-half minutes of new footage broken into three interconnected shots: |

| |

|

In the first, Jiro and Takuro continue their conversation as they walk into the back yard, and Takuro climbs the stairs to what will become his living quarters; |

| |

|

In the second, as Takuro enters the upstairs rooms, Masaki arrives looking for a haircut and is told by Jiro that the shop is not open yet, and when Takuro reappears Jiro tells him that Masaki has a UFO obsession and that “he is not right in the head”; |

| |

|

In the third, Jiro takes Takuro outside and shows him the rotating barber’s pole and warns him not to lend it to Masaki as he wants to use it to call aliens, and when Takuro heads back inside, Takada arrives to provide some expositional background on the store’s previous owner (this does explain why he is standing beside Jiro in the next shot of Takuro emptying his eel into a large plastic bucket). |

|

When Yuji pulls up in his car, is ignored by Takuro and questions the local policeman about him, the shot of Takuro positioning the aquarium tank and transferring his eel into it from the plastic bucket has been move from the end of this sequence to the beginning. |

|

There is an additional 30 second sequence of Takuro using paper templates to paint the kanji lettering for “barbershop” on the window of his refurbished shop. |

|

The sequence in which Takada arrives for a haircut to find Takuro fishing by the riverside now begins 22 seconds earlier with Takada first entering the empty barbershop and looking for its absent owner. |

|

Once inside the barbershop, the sequence in which Takuro works on Takada’s hair and converses with him begins 48 seconds earlier and sheds some light on how long Takuro has been barbering, a timeline that informs the audience that he must have learned this skill in prison. |

|

When Jiro is examining Takuro’s parole report, the scene includes 36 seconds of new footage of Takuro in the temple garden following the opening shot of the report itself, and runs for 12 seconds longer at the end, as Jiro tells Takuro that he does not need to go into so much detail when writing his reports. |

| |

|

|

In the scene in which Takuro catches food for his eel, just before he discovers Keiko’s unconscious body lying in the reeds, there is a new sequence that runs for one minute and 19 seconds in which the local policeman (I’ve been unable to confirm the name of either the character of the actor here) rides up and takes a friendly interest in what Takuro is doing, then tells him that he will be sending his rebellious son to the barbershop for a crew cut soon, and rides away. This sequence is of particular interest because of how Takuro reacts to the arrival of the policeman, standing rigidly and almost fearfully to attention in an autonomic recall of his prison days. |

|

The end of the sequence in which Takuro discovers the unconscious Keiko is edited differently to the theatrical cut, with the vocal flashback to the prison governor telling him to avoid being drawn into any kind of trouble occurring as he watches the policeman riding away. |

|

There is a one minute, 44-second long new sequence that precedes Takuro’s request that Takada, Yuji and Masaki accompany him to act as witnesses to the discovery of the unconscious Keiko, in which we see Takuro arrive back at the barbershop, outside which Yuji and Masaki are waiting. Masaki reveals that he used to run bets on horse and bicycle racing through the shop’s previous owner and wonders how Takuro would feel about a similar arrangement, prattling on while Takuro remains contemplatively silent until Takada arrives to ask how the hunt for eel food went. |

|

The wide shot of Takuro and his companions being interviewed by a detective in the police station about the discovery of Keiko starts a few second earlier. |

|

The editing of the night-time eel-spearing sequence has been subtly altered and is a few seconds longer. |

|

The sequence in which Takuro has a nightmare that sends him sprawling to the floor now has two shots of the speared eel instead of the theatrical cut’s one, and the shot of Takuro on the floor is held for slightly longer. |

|

The scene in which Misako asks the deeply apprehensive Takuro to let Keiko work at his shop has been extended by a minute to include a private chat in the kitchen in which Misako assures Takuro that once you have saved someone’s life you are responsible for them from that point on. This helps to explain why Takuro ultimately agrees to an arrangement that he is deeply uncomfortable with. |

|

The sequence in which Takada and Takuro set the first tubular eel trap is very slightly longer than before, and includes the sound of a bullfrog in the background, an animal that is shown in close-up at the end of the sequence. |

| |

|

|

Immediately following the “one month later” caption, a new one minute sequence has been added in which Takuro is observed lying on the riverbank, his eyes closed and taking in the sun. Seconds later, he is joined by Keiko, who recalls wondering why the sky was so blue when she took the overdose, and if we are absorbed into the blue sky when we die. Takuro reacts to her arrival by sitting up, and when she closes her eyes and lies down on the bank, the discomforted Takuro tellingly sits forward, putting a little more defensive distance between them. |

|

The editing of the busy barbershop sequence that follows has been slightly altered, and the shot of Keiko preparing dinner that originally opened the scene has been repositioned at its end, just before the shot of her and Takuro eating. |

|

The wide shot of Takuro at the field in which Masaki is preparing his UFO landing site starts a few seconds earlier to include Takuro arriving at the location. |

|

The scene that follows in which Takuro and Masaki converse on the fence of the UFO field has been extended by one minute and 43 seconds to include the arrival of an overexcited Yuji and his Filipino girlfriend. Yuji tries to convince Takuro to accompany them to a nightclub, then he and his girlfriend passionately kiss whilst positioned between Takuro and Masaki. Maski is fascinated, but Takuro is made deeply uncomfortable and angrily tells them to leave. |

|

The sequence in which Takasaki pulls up in his garbage truck and hands Takuro an accusatory letter has been extended to include Takuro being approached by Takada with a bucket containing the three of the six eels they caught today and offering them to Takuro, who declines on the basis that he doesn’t eat eels. When Takada suggests putting them in the barbershop tank to keep his eel company because he feels sorry that the animal is on its own, Takuro revealingly replies, “It’s better that way.” |

|

The night fishing scene in which Takada tells Takuro about the long journey that eels take to give birth and reveals that he read the sutra and the note that Takasaki glued to the barbershop door has been extended by just under two minutes to include Takada asking Takuro about his wife and compare the strength and resilience of women to that of female eels. |

|

The night-time scene in which a drunken Takasaki confronts Takuro in the barbershop and the two end up brawling includes an extra 44 seconds of fighting on the road outside before they end up on the jetty. |

|

The scene in which Jiro, Takada and Masaki confront Takuro about Keiko’s apparent departure begins 12 seconds earlier to include Takada revealing that a man named Dojima was looking for her. |

|

The editing of the sequence in which Takuro takes a boat out to release the eel has had some small changes made to the editing, but the running time of the scene is almost identical to that of the original. |

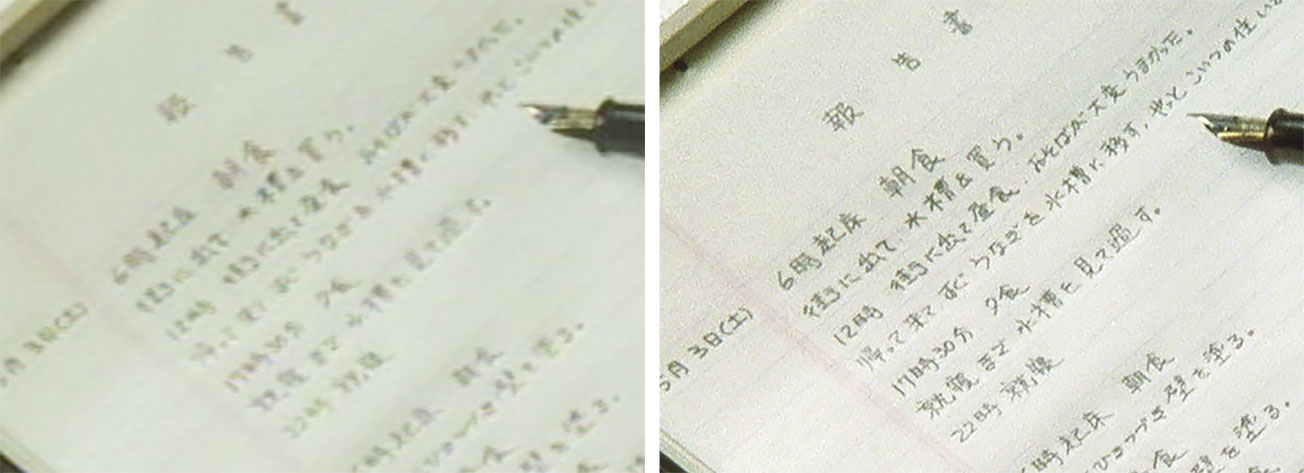

Ah, this is a slightly tricky one. Usually with Radiance releases – or at least those I’ve so far covered – we are supplied specific information about the restoration and transfer, including the resolution of the scan and the nature of the source film material. In the case of Unagi, this information is restricted to “High-Definition digital transfer,” and with Blu-ray being a digital medium, this could frankly mean anything. I say this because – oh, how can I word this without overstating the case? – while this is in almost every respect a fine transfer, the image sharpness doesn't quite hit the impeccably high bar set by those Radiance titles whose transfers we know have been restored in 4K or even 2K from the original negatives. Now don’t get me wrong, previously, the film was only available on disc in the UK on a 2012 DVD from Artificial Eye, and even by the standards of the day that had a disappointing transfer. Framed approximately 1.73:1 and letterboxed within a non-anamorphic 4:3 frame, the image detail there was unsurprisingly soft and made worse by an NTSC to PAL conversion, and the contrast was on the flat side with greyed-out blacks. The 1080p transfer on this Radiance Blu-ray represents a quantum leap over that disc. Framed in the ’s correct aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the picture quality here is far more robust, with a livelier but never aggressively graded contrast, solid black levels and correctly exposed highlights, and while there may be a slight inherent softness to the image, it’s still way sharper than the non-anamorphic SD transfer on the DVD. There is some minor variance on this score, but on the best material – usually mid-shots and medium closeups – the finer detail is clearly defined. Check the difference between the comparative screen grab enlargements (approximately 200%) below of Takuro’s report.

The 2012 Artificial Eye DVD (left) and the new Radiance Blu-ray (right)

Intermittently, usually on wider shots when the light levels drop, the image detail does soften a tad, and the warm colour palette can very occasionally have an earthier and sometimes slightly muddier feel. Nonetheless, the transfer is largely free of dust and wear, and while not in the absolute top tier of Radiance HD transfers (it’s a seriously high bar), this still a strong transfer that does feel close to how I remember the film looking on the big screen.

The film’s mono soundtrack is presented in Linear PCM 1.0, and while it may not have the tonal range of a Dolby or DTS track, the dialogue, music and effects are always clear and distortion-free, an there are no traces of any wear or damage. For a film as low key and character-centric as Unagi, this feels appropriate.

Optional English subtitles kick in by default.

The disc has been coded for both regions A and B, so should also play on unmodified North American players.

Tony Rayns (27:31)

The always interesting and hugely knowledgeable expert on Japanese cinema, Tony Rayns, provides a concise overview of director Imamura Shohei’s career, with special emphasis on Unagi, the first of three late career films for the director after a gap of several years. He highlights the role played by Imamura’s son, Tengan Diasuke, in getting Unagi into production, how different the storyline of the film is from that of Yoshimura Akira’s source novel, the work of lead actors Yakusho Kōji and Shimizu Misa and rock star turned actor Taguchi Tomorō, consistent themes in Imamura films and those specific to Unagi, and more. He also notes that this is a film that “stands up wonderfully,” a sentiment that I heartily second.

Tengan Diasuke (18:52)

Imamura Shohei’s son, writer and director Tengan Diasuke, recalls being called in to help adapt Yoshimura Akira’s source material – which he describes as a short story rather than the novel I was under the impression it was (I’ve not read it so cannot say for certain either way) – and leaving the project after a row with his father two-thirds of the way into the writing of the script. He confirms that former TV writer Tomikawa Motofumi was brought in by the producer to finish the job, only to then be unexpectedly asked by his father to return and revise a script that he was unhappy with. He talks about the characters of Takuro and Keiko and why they are in some ways kindred spirits, suggests that the film is about creating a pseudo-community and pseudo family, reveals that the barbershop set was built on the remnants of an actual former barbershop, and confesses that he understood the character of Takuro better when he saw how Yakusho Kōji played him (“he was great”). There’s plenty more of interest here.

1997: A Year to Remember (13:22)

A visual essay by Midnight Eye co-founder, Tom Mes, that looks at three key years for Japanese cinema, with particular focus on 1997, and for good reason, as it saw the release of not just Unagi, but also Kurosawa Kiyoshi’s Cure, Kitano Takeshi’s Hana-Bi, Miyazaki Hayao’s Princess Mononoke [Mononoke Hime], Kon Satoshi’s Perfect Blue, and Miike Takashi’s Rainy Dog. He talks about how the year represented a reversal of fortune for Japanese cinema, which the domestic audience had all but lost interest in, as well as the influence of what became known as the Lost Decade, the rise of the New, New Wave, and the success of Japanese films at international festivals. Another excellent inclusion.

Trailer (1:08)

“A man. A woman. An eel,” seems to be the tagline for a trailer that gives a small flavour of what it bluntly describes up front with the unfussy line, “After eight years of silence, an Imamura Shohei film.”`

Also included is a Limited Edition Booklet featuring a newly translated archival interview with Imamura Shohei, but this was not available for review.

Unagi, or The Eel as it was accurately translated for its western release, has for me lost none of its allure since its 1998 UK cinema release and if anything it has grown further in my estimation with the passing of time. Its arrival on UK Blu-ray is long overdue and thus should be enthusiastically welcomed, and while the image is not quite as crisp as some topflight HD restorations, it’s still a solid and often most impressive transfer and a giant leap over its previous DVD incarnation. The special features are also top notch, and the inclusion of both the theatrical version and the director’s cut is a massive bonus. The above small but ulktimately unproblematic caveat aside, this welcome Blu-ray ciomes highly recommended.

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review

|